Nina Livesey’s [NL] fourth chapter of The Letters of Paul in their Roman Literary Context makes the case for Paul’s letters being composed around the middle of the second century CE.

NL refers to the earlier work of the Dutch Radical Willem Christiaan van Manen [you can read the cited section on archive.org’s Encyclopedia Biblica of 1899-1903, columns 3625ff] who concluded that all of the NT Pauline letters were pseudepigraphical and composed either in the later years of the first century or early in the second. For van Manen, the event that initiated the circumstances that led to their composition was the destruction of the Jewish Temple in 70 CE. Van Manen wrote:

They are not letters originally intended for definite persons, despatched to these, and afterwards by publication made the common property of all. On the contrary, they were, from the first, books; treatises for instruction, and especially for edification, written in the form of letters in a tone of authority as from the pen of Paul and other men of note who belonged to his entourage : 1 Cor. by Paul and Sosthenes, 2 Cor. by Paul and Timothy, Gal. (at least in the exordium) by Paul and all the brethren who were with him ; so also Phil., Col. and Philem., by Paul and Timothy, 1 and 2 Thess. by Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy. ‘The object is to make it appear as if these persons were still living at the time of composition of the writings, though in point of fact they belonged to an earlier generation. Their ‘epistles’ accordingly, even in the circle of their first readers, gave themselves out as voices from the past. They were from the outset intended to exert an influence in as wide a circle as possible ; more particularly, to be read aloud at the religious meetings for the edification of the church, or to serve as a standard for doctrine and morals. [col 3626 – my bolding in all quotations]

But as Hermann Detering pointed out, and as NL concurs, there is no evidence for a “school” that could have been responsible for producing the letters between 70 CE and the early decades of the second century.

While there is evidence of Pauline letters associated with Marcion’s mid-second-century school in Rome, there is no similar evidence of the letters at an earlier period nor associated with a school of “Paul.” (NL, 200)

NL goes further and stresses that there is no other literature prior to the middle of the second century expressing comparable critical attitudes towards the Jewish law. If the Pauline letters came from that period they were anomalous. All other literature that speaks of the Jewish law up to the middle of the second century viewed it positively.

- The Hebrew Bible — the law was given as a blessing and assurance of a close bond between God and his people

- Jubilees — the sabbath was so wonderful a blessing that it was even observed in heaven; even before Moses holy persons observed the law.

- Dead Sea Scrolls — positive towards the law

- The Jewish philosopher Philo (20 BCE – 50 CE) — praised the law for containing deeper allegorical meanings

- Josephus (37 – 100 CE) — proclaimed the distinctiveness of the law in positive tones

Circumcision was likewise understood in all the canonical and extra-canonical writings most favourably. I have listed them in note form here but NL discusses them all in depth.

The change came after the Bar Kochba war that ended in 135 CE. I have written about this war several times. Two of the more detailed posts (one is a continuation of the other) are:

Continuing with NL:

“Christian” teachers and schools emerge in Rome around the mid-second century CE, after the Bar Kokhba revolt, and as a consequence of it.

The Bar Kokhba revolt and events that transpired in its wake greatly affected Judaea and Rome, both socially and politically. The revolt witnesses to a massive number of Roman and Jewish deaths (described as a Jewish genocide), the destruction of the Jewish temple, and the renaming of Judaea to Aelia Capitolina (Syria Palestina). The conquest of Judaea was likewise seen as a significant Roman victory and was greatly celebrated. According to the Roman historian Cassius Dio (c. 155-235 ce), over the approximately four-year war, Romans captured fifty Jewish strongholds, destroyed 985 villages, and killed 580,000 Jews (Dio 69.12.1-14.13). After the revolt, many Jewish captives were sold as slaves. Lester Grabbe summarizes,

. . . . Judging from the comments of Dio, however, the Roman casualties were also very high, such that Hadrian in his report to the Senate dropped the customary formula “I and the legions are well.” Aelia Capitolina became a reality, and Jews were long excluded at least officially, even from entry into the city. Only in the fourth century were Jews again formally allowed access to the temple site, and then only once a year on the ninth of Ab, the traditional date of its destruction.

Werner Eck convincingly argues that Rome considered the Jewish revolt a sizable threat and its suppression a great victory. The revolt affected territories not just in and around Judaea, but also the neighboring regions of Syria and Arabia. In response to it, Rome transferred many of its military regiments along with its best generals to the region. One such general was lulius Servus, whom Hadrian had transferred from Britain to Judaea. With Britain recognized as one of the most significant military outposts of the Empire, the relocation of Servus to Judaea is an indication of the seriousness with which Rome regarded the revolt. There is likewise the suggestion that Rome may have called up as many as twelve or thirteen legions to assist in the revolt’s suppression.

Rome greatly celebrated its conquest of Judaea. In recognition of the victory, Hadrian was named imperator. With this new honorary designation, he bestowed the highest military award (ornamenta triumphalia) on three generals charged with the suppression of Jews and the destruction of Judaea. The Roman Senate likewise dedicated a monument to Hadrian in the Galilee near Tel Shalem equal in prestige and size to the Arch of Titus in Rome. Moreover, the change in name from Provincia Judaea to Provincia Syria Palestina was a unique event in Roman history. Judaea no longer existed for Rome after the Bar Kokhba revolt. Never before or after had a nation’s name been expunged as a consequence of rebellion. Eck remarks, “It is not because the Jewish population was much reduced as a result of losses suffered during the war that the name of the province was changed. … The change of name was part of the punishment inflicted on the Jews; they were punished with the loss of a name.” (NL 200ff — though not mentioned by NL, it may be of interest to note that the area of Galilee has yielded no archaeological evidence of having been involved in the Bar Kochba revolt; Galilee was also the region to which Jewish life gravitated after Hadrian’s genocidal suppression in Judea and Jerusalem.)

* For posts addressing the evidence for the messianic character of the widespread Jewish uprisings under Trajan see

Reconstructing the Matrix from which Christianity and Judaism Emerged

Rebellion of the Diaspora — the world in which Christianity and Judaism were moulded

The Troubled “Quiet” before the Jewish Diaspora’s Revolt against Rome: 116-117 C.E.

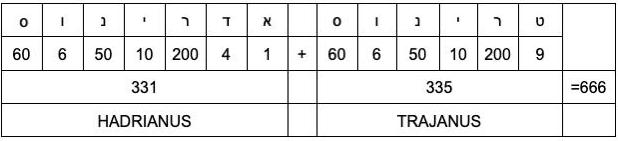

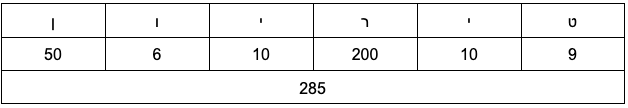

Another scholar who has viewed this same war as pivotal in relation to another book of the New Testament is Thomas Witulski’s research on the Book of Revelation. (Witulski further finds significance in the Jewish uprisings under Trajan that preceded the Bar Kochba war, uprisings that another scholar has argued were messianic in nature and anticipating a rebuilding of the Temple*.)

NL writes:

Events leading up to and following the Bar Kokhba revolt can be understood as influential to the development of Pauline letters. For, the Bar Kokhba period saw not only massive destruction, death, and the removal of the Jewish population from Judaea but also the call for a ban on circumcision and the destruction of Hebrew scriptures.20 Rulings against the Jewish practice of circumcision and Jewish writings redound in discussions of these themes in texts dated in and around this period. In addition, treatments of Jewish law and circumcision in biblical and non-biblical texts dated to this period reveal a dramatic downward shift in their value. Comparably dismissive and/or derogatory assessments of circumcision and Jewish law do not surface in texts dated prior to the end of the first century. Discussions of the rite of circumcision dated at or after the Bar Kokhba revolt parallel those found in Pauline letters. (NL, 202f — on footnote 20, a reference to Jason BeDuhn’s The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon, I have been unable so far to locate the source for the “destruction of Hebrew scriptures”, though I suspect it will be found in the rabbinical references in Peter Schafer’s Der Bar-Kokhba-Aufstand.)

It is in the context of a widespread hostility to Jewish national markers (especially circumcision) most notably in the aftermath of the horrific carnage of the Bar Kochba war, that NL finds a place for the Pauline letters with their hostility towards the same Jewish law, most notably circumcision.

The assessment of Jewish law found in Galatians finds no parallels in primary sources dated up through Josephus (c. 100 CE). . . .

A rather dramatic shift in the assessment of circumcision occurs in “Christian” writings dated after Bar Kokhba. The Epistle of Barnabas (c. mid-second century CE) and Justin’s Dialogue with Trypho (c. 160 CE) roundly and at times pejoratively debase the practice of circumcision. These writings alter the signification of Abraham’s circumcision and diminish its association with the covenant. The Dialogue with Trypho, disassociates circumcision from a state of righteousness/justification, and removes its association with the covenant. These writings likewise variously interpret the practice of circumcision as inessential, or worse, as wrong/inappropriate. In addition, Justin ties circumcision to the negative social situation of Jews in the period after the Bar Kokhba revolt, and thus provides an indication of the revolt’s influence on at least a portion of his assessment of the rite.

These second-century texts reduce in value and alter in signification the circumcision of Abraham, the patriarch with whom the rite was constituted. (NL, 208, 215f)

NL is addressing a major subfield within the scholarship of the Pauline letters:

Pauline scholars have worked tirelessly in attempts to account for the devaluation of Jewish law in the Pauline corpus.” Indeed, the scholarship in this area is recognized with its own subfield, “Paul and the Law,” with various “perspectives” offered. (NL, 223)

Over half a dozen pages NL traces the attempts of scholars to understand Paul’s view of the circumcision question and the Jewish law. The answer, NL believes, is to be found in the controversies generated by Hadrian’s ban on the practice as part of his program to eliminate Jewish identity.

Continuing…..

Livesey, Nina E. The Letters of Paul in Their Roman Literary Context: Reassessing Apostolic Authorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024.