Critique of the Gospel History of the Synoptics

by Bruno Bauer

Volume 3

—o0o—

247

§ 86.

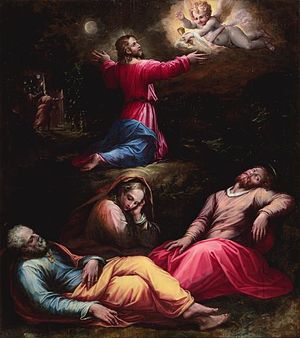

The struggle of Jesus’ soul in Gethsemane.

1. The report of the synoptics.

After finishing the meal, Jesus went with the disciples to the Mount of Olives, and when they arrived at the Garden of Gethsemane, he told them to sit and wait while he went a little further to pray. He took only three with him, Peter and the two sons of Zebedee, and told them that his soul was deeply grieved, even unto death. He asked them to stay and watch while he prayed, and he fell on his face and prayed to the Father, asking if it was possible to take the cup from him, but added that he would do the Father’s will, not his own. When he returned to the disciples, he found them sleeping, woke them up, rebuked them, and urged them to stay awake. He went away a second time to pray the same prayer, and upon returning, found the disciples sleeping again. He went away a third time to pray, and finally, upon returning and finding the disciples still sleeping, he said to them: — but of these words later!

248

Thus, in essence, Matthew and Mark tell the same story in the same words, except that the originality of the latter’s account, apart from a few more appropriate and precise phrases, is revealed first of all in the fact that it says of the second prayer only that Jesus prayed again with the same words as before, while Matthew turns the words of the first prayer to the effect that Jesus now already – why the third prayer? – Jesus had already said, presupposing the impossibility of what he asked for in the depths of his soul (C. 26, 42): if it is not possible, Father, that this cup pass over me, then let your will be done. Then the prayer in Mark is more urgent, the struggle of Jesus is more serious and the condition under which this struggle alone is possible is really pronounced: Father, says Jesus 14: 36, everything is possible for you, take this cup from me. Only narratively and in the indirect manner of speaking Mark had previously determined the content of the prayer to the effect that Jesus had prayed that this hour, if it were possible, would pass him by: Matthew formed the first prayer from this: 26: 39, Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from me!

It is unlikely that Matthew changed his account with the intention of softening the matter, but even if it happened against his knowledge and will, he already represents the transition to the position of those who took offense at Jesus’ struggle in the garden. He may have left the account in its positive form simply because it was given that way, but eventually he could have decided to remove it or at least not take it in the serious form that Mark presented it.

249

Beside this direction, which has always asserted itself in the church, even among those who did not understand the suffering of Jesus’ soul as a purely personal, but as a vicarious one, but even in the circle of the latter view, another direction asserted itself, which was pleased to consider and to depict the struggle of Jesus’ soul as a rather gruesome, terrible and lacerating one. Luke has already taken this latter direction, although he still largely agrees with Mark’s interpretation that Jesus’ struggle was an inner spiritual struggle, namely the struggle in which he had to decide whether or not to accept the destiny assigned to him.

Luke has so little desire to take up the details of the original report that he does not even tell us where the struggle of Jesus’ soul and the imprisonment took place. He simply states (in chapter 22, verses 39-40) that Jesus went out to the Mount of Olives as was his custom, and “when he arrived at the place” – it is clear that this presupposes a specific location, which is only mentioned in another account – he told the disciples – but Luke does not say that Jesus took only three of the disciples with him, leaving the others behind. He also does not say that Jesus told these three to stay behind while he went further away to pray. Nor does he say that Jesus told the disciples to wait and only later, when he found them sleeping upon his return, urged them to be watchful and pray. Rather, by combining all the details, he presents the matter in such a way that Jesus advised all the disciples to pray from the beginning. Of course, Jesus could not have told them to stay behind, but he also could not have urged them to pray if it happened involuntarily and without his will that he was separated from the disciples and compelled to pray. He was carried away from them about a stone’s throw, thus being forced by external circumstances into the situation in which he felt compelled to pray, and he offered a prayer that was essentially the same as the one reported by Mark.

250

The confusion is therefore very great. Just as great at the end of the report.

Having risen from prayer, Jesus goes to the disciples and finds them asleep with grief. But – not to ask whether sorrow should not have kept them awake, as it usually does, not to notice that Mark knows how to explain their sleep quite differently, namely from the weakness of the flesh, which does not always obey the spom of the spirit – why from sorrow? Jesus had not even told them that his soul was deeply grieved, even unto death, and they had no idea what was happening when their master was forcibly taken away from them. Then Jesus says to them, as before, pray! but now – since immediately, while he is still speaking in this way, the betrayer comes with the crowd – the necessary part is missing, that Jesus calls them to endure, because now the betrayer is near – – thus a word, which could not be missing, so that it would be certain, that Jesus had foreseen the destinies of his last hours also up to the point, that the betrayer would come just now. Luke has taken up the points of incidence of the original report by chance and has cancelled the rhythm that brought them about.

But would he really have had the writing of Mark in mind? We have proved it! But is his report, since he only knows about a continuing fight, not about a threefold beginning of it, not significantly different from that of Mark? Is it not something quite different when it is said that an angel appeared and strengthened Jesus, and that the Lord’s struggle was so violent that his sweat became like drops of blood falling from the earth?

251

Answer: if Luke wanted to let the angel intervene for the strengthening of Jesus, then he had to let it be with a single, or in one process continuing fight, because he would have been very embarrassed, if he would have wanted to bring the angel also with the condition of a threefold beginning of the fight. If the angel would have intervened immediately at the first approach, the two following approaches would have been incomprehensible and one would have to ask, where the power remained, which the angel had brought from heaven; or if the angel should come only at the third approach, then the question arises, why he did not come earlier, why rather only in the moment, where according to Mark the fight is already decided also without heavenly miracle power. So the angel and One fight, or three times fight and No angel!

However, although Luke chose the first assumption to make the matter more wonderful and transcendent, he cannot deny that he copied a report that shows the struggle unfolding in several stages. After reporting that an angel appeared and strengthened Jesus, he tells us that Jesus prayed with even greater effort, and finally that drops of blood dripped from his forehead. Here are the traces of the triple approach, but now it is also clear that the angel was summoned by Luke at a very inappropriate time, since despite his heavenly encouragement, he could not prevent Jesus’ inner struggle from becoming even more intense and eventually becoming bloody. Not only is the angel unnecessary, but he is also highly disruptive, as his intervention turns the matter in such a way that Jesus no longer decided his struggle with the divine will by his own resolution and dissolved it in complete surrender to his destiny.

252

Luke’s account is resolved on all sides. Now another look at Mark!

At first we must be astonished how only the three chosen ones of the remaining disciples are initiated into the secret of the following battle, even if only in a distant way, as if it were a sublime mystery or a pompous spectacle. It may be pompous with this threefold approach, at least it should become pompous; but in what the sublime and great should lie, we would not know how to find, since, on the contrary, we call the martyrs of history great and worthy of our esteem only when they endure their sufferings calmly by virtue of the self-assurance of their principle and their justification, and thus prove that they stood just as much above the external power and force of the principle they fought as they knew how to overcome it spiritually in their higher self-awareness.

What is the use of this threefold approach to the struggle? We would not know, if it should matter, how it is founded in the nature of the thing. If Jesus has already confessed once: not my will, but yours be done, then this confession is not only weakened, but downright annulled, if a second, even a third beginning of the struggle follows, and it is still always only about the same confession. But it is known that everything great and significant in sacred history must happen three times if it is to prove itself great.

The resolution of the original report will be completed if we listen even more closely to the words of Jesus to the disciples. They are to watch while Jesus walks apart! In what way? Afterwards, indeed, but – we must say at once – only afterward, when Jesus finds them asleep on his first return to them, is it said: watch and pray! Why was this not said earlier? Because Mark did not always want to write the same words, because he wanted to increase the number of words, because he believes that every reader of his writing would be reminded by the keyword: watch! of the admonition in Jesus’ speech about the last things (13: 33. 37): watch and pray! But the disciples had not yet read the Gospel.

253

What kind of sentence is it finally, when Jesus finds the disciples sleeping for the “second time” and says: “Sleep the rest of the time and rest – as if they had not slept before! – the hour has come – well, then they may and can sleep even less! – The Son of Man will be delivered into the hands of sinners. Arise, let us go! – but in the same breath Jesus had told them to sleep! How do they have time to do so, when the Lord says at the same moment: “Behold, my betrayer draws near!

Mark considered it necessary that the Lord, at the moment when the last battle and the catastrophe broke out, showed factually, seriously, that he went to meet his fate with free will, but the original evangelist could not depict this moment in any other way than that he first put Jesus with his destiny – compare Ps. 39, 10 – into battle and discord, before he showed how the tolerator voluntarily submitted to his fate.

This was the necessary consequence of pragmatism, that Mark had let Jesus prophesy his end already beforehand and in the most definite way. If it was now important that Jesus in the end should once again and quite reliably express his surrender, then he was not only allowed to speak, no longer only to speak and prophesy; he now had to feel, to mourn, to be afraid, to faint, in order to regain his strength through his inner struggle. This was also the necessary consequence of the lack of artistic composition in the Gospels, of the lack of a clear depiction of the historical struggles of their hero, in general of the complete lack of human, great, dignified struggles – we mean: such struggles in which also the opponent is held great and important – that now finally the struggle of Jesus against the opposing powers collapses into such a suffering of the soul. Other historical or epic heroes do not need such a struggle with their weakness, because they have proved themselves until death, if death is their lot, in the struggle with great and important historical powers.

254

We have now to see how the Fourth has reproduced the report of Mark.

2. The report of the fourth.

On the contrary, he did not reproduce it at all for his readers. After the dogmatic lecture, in which he had long since risen above all historical collisions and had given the disciples all possible information about the purpose, success and necessity of his death, as well as about everything that could only somehow be related to this dogmatic locus, he was not allowed to present his Lord again as hesitating or even as despairing. The Jesus who, in the long speech that he gives to the disciples after the last meal, speaks as if he already saw himself reinstated in the glory that he possessed before the creation of the world, which he had left only for a moment and to which he returns again to send the Paraclete to his own, the Jesus to whom eternity belongs, could not be troubled by the imminent death that paved the way for him to the seat of his glory.

The fourth was not allowed to take up the report of his predecessor, because his Jesus had become another than that of Mark. Probably now, in order to fill the gap, so that the traitor would not appear immediately, as Jesus goes out – for the space that the evangelists use for writing and fill with their notes turns into time for them – perhaps also merely because he always introduces the scenes ponderously and laboriously and has to prove the cleverness of his pragmatism, he has explained very precisely (C. 18, 1. 2), where Jesus went with the disciples after the last meal, where that garden was located – the name of which, however, he is very careful not to mention in the writing of Mark – and how it happened that Judas went there with the band of the henchmen -!! he knew that Jesus often met there with the disciples!! – These are all things which Mark was justly indifferent to, and which are most indifferent to us also, because they explain nothing, for that a certain garden, called Gethsemane, had been a common place of abode, is a novelty which is much too unexpected for us, that it was Jesus’ custom, that it was Jesus’ custom to stay here in the open so long into the night is too improbable, and this clever pragmatism is also useless, because Judas, if he should find Jesus, could and should have found his victim in that well-known illumination of the ideal world, where everything is bright or somnambulistic, even in the greatest darkness. Mark has placed the whole in this illumination.

255

But if the fourth once saw that he had to omit the report, then he should have omitted it only completely and not in another form and not nevertheless in such a way that it takes up all essential elements of the same, in another place.

During the last Passover feast some Greeks, who had come because of the feast – thus incongruously enough proselytes, not pure Gentiles are, like the Canaanite woman of Mark, the centurion of Matthew – had become attentive to Jesus. They wished to see him. As if they could not see him daily, hourly, now, instantly, as if it were a closed, mysterious thing, a hidden sanctuary, an Oriental despot hidden in the innermost part of his palace, they turn to Philip; the latter, as if he were not close enough to the person of the prince or was not allowed to come alone and directly to the terrible despot, presents – how vividly! – the matter to Andrew, and only now do they tell it to the Lord. The latter, who considers and uses everything only as an occasion to speak of his person, immediately exclaims: “The hour has come when the Son of Man will be glorified. Verily, verily I say unto you – (the reader of the Gospel adds to himself beforehand the intermediate thought, which however the present listeners should probably have heard, that death is the way to glorification) – the wheat seed, if it does not die in the earth, remains lonely and does not bear fruit. “But what is the meaning of the saying that was originally intended (Mark 8, 35) to call to follow Christ, the saying: “whoever loves his soul will lose it, etc., a saying that the fourth then continues to comment on in his laborious manner: “whoever serves me, etc., etc.?

256

Immediately after this, here completely inappropriate, at least not motivated and properly guided saying, Jesus returns to his true subject, his own person, and since he had previously aroused the thought of death, he cries out: now my soul is troubled, as in Mark: my soul is deeply grieved to the point of death; and what shall I say? as he is really tortured by the possible choice between two decisions in Mark; Father, save me from this hour! as in Mark: Father, take this cup from me! But for this reason I have come to this hour! as in Mark: yet not what I will, but what you will! John 12, 20 – 27.

That Jesus, in one breath after those words of resignation, forces the Father to glorify him, cannot surprise us anymore, considering the well-known manner of the fourth: he has taken what is connected but also separated in Mark, the talk of Jesus about his sufferings and the glorification that followed it, directly together, and he has taken a core saying from Jesus’ talk about the duty of his followers to deny themselves and squeezed it between the two pieces of the Primal Gospel that he presses together here, or rather he has taken these three members of the Primal Gospel: Mark 8, 31-38, the disclosure that he must suffer, the admonition to his followers brought about by Peter’s foolishness, and the transfiguration, partly reworked into an abstract, partly roughly excerpted again in individual key words, and threw everything together in a chaos. In this chaos, of course, he could now also throw in all the elements of the original report of the battle of souls without further ado, since there was once talk of death. The matter is clarified. We therefore only briefly note that if the thunder of glorification takes the place of the heavenly voice that was heard after the transfiguration, the same thunder that some thought to be the voice of an angel (John 12:29) must also be the ministry of the angel who, according to Luke’s account, strengthened the Lord in his anguish. It is not worth the effort, however small, to resolve the following report up to the end, where Jesus, although he has withdrawn (C. 12, 36), nevertheless suddenly stands there again and cries out and, since he from now on no longer speaks before the people, recites the sum of his dogmatics *). We return to the Greeks.

*) Just as little it is worth the effort to expose the speeches, which Jesus holds after the last meal, in their lack of content, in their tautologies, inconveniences, to prove the misunderstandings, which help the halting speech, as groundless and to dissolve this whole creation – all turns, which would have to be considered here, we have already dissolved in the criticism of the fourth gospel. Only the dogmatic content as such is to be considered, when the time is to be determined, in which this gospel was written.

257

But we can’t find them again! Despite the effort they made to register, they do not appear and Jesus gets lost in reflections, to which they could only give rise in a very remote way or at least only indirectly: but once those reflections are initiated, the poor strangers are forgotten, because the Fourth [Gospel writer] was only interested in putting his Lord in a mood that, according to his presuppositions, he should have kept him away from, and lending him thoughts and words that should have remained foreign to him.

258

The Fourth [Gospel writer] brings strangers, Greeks, onto the stage because the Lord had previously connected the necessity of his death with the necessity that he must lead the foreign sheep to the fold of his own. But if this connection had already been portrayed extremely unsuccessfully and the composition completely failed *), then, if it were possible (but everything is possible for the Fourth), the confusion had to become even greater when the Greeks were already standing there in the flesh, the messengers of the pagan world had already personally announced themselves, and the joy should have been even greater. Mark, Luke, and Matthew knew how to welcome such messengers.

*) John 10, 16 – 18. See Critique of the Gospel History of John p. 383 – 388.

In a gospel that never lets us come to our senses, we cannot be surprised when the author of it uses the words that Jesus speaks to the disciples in the garden at the approaching arrival of the betrayer: “Come, let us go! – because he has no place for them afterwards; as if they should not be missing at all; as if they were magic words! – The Lord speaks after the conversations at the end of the last supper **) – and still lets him stand there afterwards and give a long speech, so that we have to think that he has delivered the sayings of three chapters (15. 16. 17.), this extensive Christology and dogmatics – roughly the fourth part of the entire content of the Gospel – between the door and the threshold! —

**) John 14, 31 : εγειρεσθε αγωμεν εντευθεν Mark 14, 42 : εγειρεσθε αγωμεν

————————-

Like this:

Like Loading...