Criticism of the Pauline Epistles

by

B. Bauer

First Section

The Origin of the Galatians Epistle

1850

3

Preface

We will put an end once and for all to the mistakes and unsuccessful attempts of the apologists, who started from the assumption that it is both possible and necessary to integrate the Pauline letters with their historical presuppositions into the historical course of Paul’s life as reported in the Acts of the Apostles, through a correct framing of the question.

Having demonstrated the Acts of the Apostles as a work of free reflection, and moving on to the question of whether the four letters – (the letters to the Galatians, Romans, and the two Corinthians) – which have never before been suspected of inauthenticity, actually possess the character of Pauline originality so indisputably, as Dr. Baur suggests*, that it is impossible to imagine what right critical doubt could ever have against them, it is no longer conceivable to us to reconcile presuppositions of letters with the information provided by a work of historical fiction, which, to express it with caution, could also be spurious.

*) The Apostle Paul, p. 248.

4

If, however, these letters are proven to be spurious, then the real work of research takes the place of the chimerical efforts of theologians, which exposes and explains the contradiction between the historical presuppositions of the Acts of the Apostles and the so-called Pauline letters, thus abandoning the attempt to reconcile them and instead seeking the real historical relationship between the Pauline letters and the Acts of the Apostles.

The question properly framed is: which of these letters were written before the Acts of the Apostles, and which were written after? Which letters were known to the author of the Acts of the Apostles and served as its basis – and in which letters is there evidence of knowledge of the presuppositions of the Acts of the Apostles, and which of the authors of these letters had the historical work in mind and used it?

The overall subject of investigation is the historical sequence in which the letters and the Acts of the Apostles were written – dealing with the process of Christian consciousness that culminated in these works – as well as the relationship of these works to the Gospels.

While one of the most important sub-questions is whether the notes of the Church Fathers about the apostolic letter collection of Marcion are as reliable and indisputably secure as their accurate descriptions of the Gospel in his possession, the great and general interest of the following investigation lies in the fact that it will provide us with the knowledge of that revolution which still resonates and continues in the letters designated by the ecclesiastical canon as Pauline – and finally, it is not the least benefit of the correct framing of the question that we can search for and demonstrate the work of that Judaism, which we have demonstrated in the Acts of the Apostles – that Judaism which is the eternal opponent of original creation, self-power, equality, and pure, plastic form – that Judaism which, in the slackening of the present, finally believed to have found its true life element, now also in the letters that are supposed to originate from the first and greatest opponent of historical Judaism.

5

We begin with the letter to the Galatians.

While Dr. Baur*) identifies it as the document of Paul’s first struggle with his Jewish-minded opponents, while according to de Wette’s opinion**), “it bears so much the stamp of the spirit of the Apostle Paul that there is not even the slightest doubt against the ecclesiastical tradition that attributes it to him,” while Nückert***) does not agree with Winer’s judgment, who even places it above the letter to the Romans, but finds the presentation, “regarding the arrangement of the material, very excellent, the order of the topics well thought-out and highly illuminating,” while he †) clearly and unmistakably recognizes the true Paul in the letter, to the extent that he considers the question of the authorship to be the easiest among all the questions that can be raised about the letter – we will rather prove that the author is a compiler who used the letter to the Romans and the two letters to the Corinthians during a journey, whose characteristics are contained in the following lines.

*) ibid., pp. 257-258.

**) Introduction, p. 130.

***) in the commentary, pp. 336-337.

†) ibid., p. 293.

6

Once the compiler is revealed, we will first determine the mutual relationship between the letter to the Romans and the letters to the Corinthians, and their origin.

————————–

7

As we leave these questions for the time being, such as whether the Apostle’s relationship with the Galatian community could have necessitated him to assert his apostolic authority in the greeting (Chapter 1, 1-5), whether his title as an apostle must necessarily be placed next to his name (“Paul, an apostle”), whether it was really necessary to immediately state in the first sentence (“not from men nor through man”) that he was not sent by men and that his commission did not come to him through human mediation, and whether a historical hero would declare his legitimacy in this way during a dispute – we turn to the following study, which will answer these questions as unnecessary and in a completely different sense than has been done so far in the apologetic interest.

————————–

8

Introduction

(1: 6-10)

Immediately after the greeting, there is the accusation and astonishment over the Galatians’ quick defection – immediately, without any preparation or transition. But why so abruptly? Did it perhaps make it “impossible for the apostle to apply art and take detours” because of the strong agitation of his mind? However, a natural introduction, connection to given information or previous negotiations is not a detour, it belongs to the absolutely necessary, not to the excess of art.

But was the defection of the Galatians a matter already negotiated between Paul and them? Did a negotiation precede that he could connect to without further ado? But then the apostle would still have to touch on this negotiation, he would have to refer to it – he could not (v. 6) simply say, “I wonder that you have turned away so soon.”

The determination “so soon” does indeed tie in with a common assumption – “so soon”*) i.e., as you and I know, as already discussed and negotiated – the formula brings forth the appearance as if there had been a negotiation that the apostle could refer to from the outset – but the appearance remains hollow, the assumption on which the formula is based is not explained, the author does not justify his right to that formula – the formula is intended to point to a point that is visible to both the Galatians and the apostle – in fact, it points to nothing.

*) οὕτω ταχέως

9

As we pass by, we note that Judaism is already such a distant sphere for the author that he calls turning towards it a falling away from the true God, as he describes the Galatians (v. 6) as “called in the grace of Christ.” We immediately notice how strained and unsure the explanation is that the author gives in verse 7 of the other gospel to which the Galatians have turned away, that is, how anxious the transition to the issue that concerns the author is.

“Which is not another,” refers to the “other gospel” that the Galatians have fallen away from *), and should, therefore, explain the nature and origin of it, but this connecting and explanatory formula only picks out the category of the gospel in general from the striking and explanatory determination of the “other gospel” and thus says the following sentence: “Which is not another, but there are some who trouble you and want to pervert the gospel of Christ.” Certainly, this at first unjustified turn is not carried through purely – it was not possible – it is crossed by the other turn that aims to explain the striking composition of the “other gospel” and wants to interpret the origin of this foreign, false gospel – that is, neither of the two turns is carried through purely – the author writes so floating, unsure, and confused, as it is impossible for someone who intervenes in personal, real relationships and has to defend his principle and his entire essence.

*) v. 6 εἰς ἕτερον εὐαγγέλιον, v. 7 ὃ οὐκ ἔστιν ἄλλο· εἰ μή …..

10

Furthermore, how affected and unfounded is the following hyperbole in verse 8: “But even if we or an angel” – an angel who, although higher than us, is the next higher and can be compared to us – an angel who, although has heavenly authority, is not too distant from us, as we also possess almost heavenly authority.

Therefore, “let him be accursed” who preaches to you a different gospel than we have preached to you – when did the Apostle say this to the Galatians, so that he can continue (verse 9): “As we said before and now I say again?” During a previous visit? Or since we know nothing about repeated interactions with the Galatians, during his first and for now only visit? But why does he repeat the curse after the words “and now I say again?” Was not the first pronouncement of the curse already a repetition of it, if he had laid it on any perversion of his gospel during his first visit among the Galatians? Does it not ultimately come down to the fact that he is only repeating the curse now, if he writes it again after the explicit remark “as I say again”?

Indeed, it comes down to this frigid and helpless turn of phrase – and yet he also wants the readers to remember an earlier statement, that they should recall his anathema against the heretics – he wants to refer to an earlier statement – but then it also remains that the current repetition of the curse, and at the same time the explicit remark that he is repeating it twice now, is highly inappropriate and chilly.

11

Even if he only wrote the curse once and referred to this single instance as a repetition of an earlier expression, this reference to a previous threat and the repetition of the curse appears cold and affected.

The inappropriate and confused reference to an earlier statement and the repetition of the curse stems from the fact that the author reads in 2 Corinthians how the apostle fears that the Corinthians are susceptible to deception, and he reads there how the author warns of someone who would preach a different gospel – a different one which the Corinthians did not receive from him *) – in 1 Corinthians he reads how the apostle claims full authority for the curse and exercises it against the apostates**) – these phrases and keywords, which are naturally brought about in the Corinthian letters and defend the honor of their originality through the context in which they stand, the author of the Galatian letter has appropriated somewhat carelessly and combined them so disorderly that he cannot deny the plagiarism. While the author of the 2nd Corinthians fears that his readers are susceptible to diabolical deception, he immediately confronts the Galatians with amazement at their quick apostasy – while the former warns against anyone who might come with another gospel, the latter in verse 7 clumsily refers to the people who must be among the Galatians and distort the gospel, and then drifts off into the senseless impossibility in verse 8 that he or an angel should teach another gospel – while the former curses the real enemies of Christ, the latter hurls it at the impossible creatures of his imagination – finally, the ambiguity of meaning in which the author of the Galatian letter speaks of a repetition of his curse over the teachers of another gospel is now explained: he has already spoken of such false teachings before, namely he has the warning of the second and the curse of the first Corinthian letter before his eyes – but since he cannot completely suppress the feeling that the Galatians have not heard this warning and this curse, he makes those futile efforts to transform the repetition of an earlier statement into the momentary repetition of an (unwritten) sentence.

*) 2 Cor 11:3-4 εὐαγγέλιον ἕτερον , ὃ οὐκ ἐδέξασθε

**) 1 Cor 16:22 εἴ τις …. ἤτω ἀνάθεμα.

12

We will now completely dispel any doubt about whether the author really used the Corinthian letters as a plagiarist, after noting how cold and clumsy it is when he refers to himself after the anathema and relies on the fact that he (verse 10), while he had previously sought the approval of men, now cannot possibly strive to please men. Clearly, he wants to justify himself because of the curse *) – I cannot do otherwise, he wants to say, I have the right to be so forceful – so he feels, he fears that his curse might make an adverse impression on his readers as being too harsh, too abrupt, too striking? Is he making excuses? Does he fear the judgment of men? Well, then he is still dependent on the judgment of others – he lacks the independence that he attributes to himself as a gain of his new servitude in Christ’s service – he refutes his anxious claim.

*) V. 10: ἄρτι γὰρ.

13

And why does he refer to his former life? Why this affected contrast between his current independence and his previous dependence on the judgment of men?

Why? He wants to speak about his past, his conversion – he wants to show that he has stood independently from the moment of his calling.

————————–

The Interpretation of the Apostle

(1: 11-16)

With a very significant introduction, he notes in verse 11: “But I certify you, brethren, that the gospel which was preached of me is not after man.” Really? The Galatians did not know that? Have they not heard it from him before?

What an important announcement! How cold and forced this attention to a fact that must be known to a community founded by the apostle of the Gentiles.

Finally, one has also asked and pondered how the apostle suddenly comes to call the apostates whom he had previously harshly rebuked, “brethren.” The answer is given by the First Epistle to the Corinthians, which the author has before him and from which he borrows the introduction in which the apostle begins his significant revelation about the last revelations of the Lord.*)

*) 1 Cor 15:1 γνωρίζω δὲ ὑμῖν, ἀδελφοί, τὸ εὐαγγέλιον ὃ εὐηγγελισάμην ὑμῖν.

Gal 1:11 γνωρίζω γὰρ ὑμῖν, ἀδελφοί, τὸ εὐαγγέλιον τὸ εὐαγγελισθὲν ὑπ᾽ ἐμοῦ

14

The frosty and awkward style of this entire introduction is also reflected in the way the supposed apostle speaks about the contrast between his former zeal for the law and his calling by the Lord. “You have heard,” he says in verse 13, “of my former life in Judaism” – “heard” – it sounds like it’s from other people, without Paul’s involvement and communication – “heard” – like a foreign story, which, however, could not have happened to them by chance.

The communities founded by the apostle, however, must have known him and could not have heard of his story like a stranger’s. His contemporaries and communities had to live in this story and its memory.

And when did “Judaism” **) stand before the communities as this closed, antiquated, and foreign world? Only when the struggle against the law was decided and Judaism became the category of the outdated and the pure antithesis to Christianity.

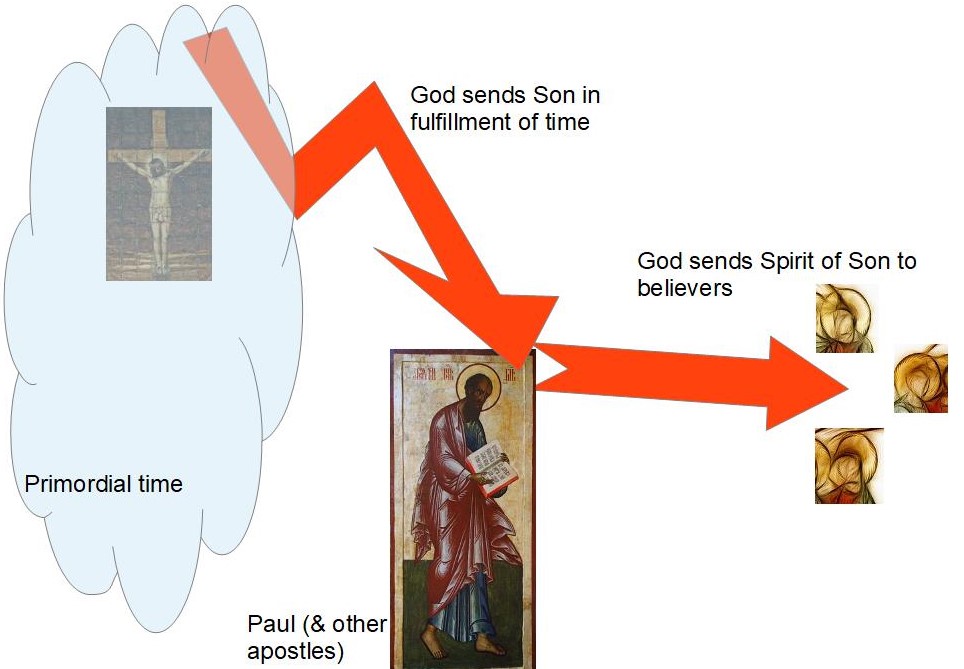

One more thing! Is “the revelation of Jesus Christ,” through which the apostle received his gospel in verse 12, a single act – that specific event that the Acts of the Apostles reports? Initially (v. 12), it is still the general medium through which the apostle received his gospel – in the following (v. 16), it is determined by the contrast with the apostle’s former Jewish way of life, but the Father is the Lord of the revelation, who reveals his Son “in” the apostle, and the revelation itself can thus unfold and extend as an internal one without specific temporal sections. However, when the apostle refers to the nets he cast into Arabia as a result of his calling and revelation, and then notes in verse 17 that he “returned” from Arabia to Damascus, the calling does become a specific event and Damascus becomes the location of the revelation – that is, only involuntarily, only finally and through a lost keyword does the author reveal that he was familiar with the view of the apostle’s conversion, according to which it was caused by a miracle and specifically at Damascus.

**) ὃ ἰουδαϊσμος

————————–

15

The Apostle’s Relationship to Jerusalem.

(1: 17 – 2: 14.)

After the Apostle has emphasized from the beginning that his gospel is his personal property, the privilege of his personal apostolic consciousness, based on a revelation he received, and that the execution of it is his specific mission, he finally comes to a detailed proof of his personal authority and special entitlement: he has had almost no contact with Jerusalem and the original apostles (C. 1, 17-24), his independence, his autonomous legitimacy, and the uniqueness of his sphere of activity is acknowledged by the original apostles themselves (C.2, 1-10), and he finally opposed Peter ruthlessly when he was openly in the wrong (C. 2, 11-14).

16

Only three years after his return to Damascus does he go to Jerusalem (Gal. 1:18-19), where he seeks out only Peter, stays with him for only fourteen days, and sees no one else but James, the brother of the Lord. But why (v. 20) the deliberate affirmation: “In what I am writing to you, before God, I do not lie”? He means that everyone knows that the apostles always had their permanent residence in Jerusalem – he believes that everyone must therefore assume that he has also seen and spoken to everyone else, unless he explicitly rejects and corrects this assumption – hence the strong oath that he borrowed from the Romans *), but unfortunately is based on an assumption that makes what he is swearing to a matter of impossibility. If he stayed in Jerusalem for fourteen days, associated with Peter and James, and the presence of the other apostles in the holy city was a given, as his oath indicates, then it was impossible for him not to have seen them.

*) Gal. 1:20 ἃ δὲ γράφω ὑμῖν, ἰδοὺ ἐνώπιον τοῦ θεοῦ ὅτι οὐ ψεύδομαι.

Rom 9:1 ἀλήθειαν λέγω ἐν χριστῶ, οὐ ψεύδομαι Further: 2 Cor 11:31

With the utmost care, he then describes his subsequent trip to Jerusalem as the second one. “Then,” he says (Gal. 2:1), i.e. after that first trip, “I went up again” to Jerusalem, i.e. again, like the first time, “after a period of fourteen years,” so that no trip to Jerusalem took place during this interim period – yes, to maintain his independence completely, so that the fact that he presented his gospel to the leaders in Jerusalem does not make him appear dependent and dependent, he declares that he went to Jerusalem “as a result” of a revelation that had been given to him.

17

Until this point, his presentation, although the eagerness of the piled-up exaggerations gives it a squinting appearance, would be at least comprehensible, but in the following sentences he confuses himself with his anxious restrictions and exposes the clumsiness of his invention.

“I presented to them,” he reports in verse 2, “the gospel that I preach among the Gentiles” – to them! – “but privately to the influential” *) – “but?” – so the influential people with whom he conferred privately were different from those to whom he presented his gospel? But who could the latter be? So the expression “the influential” is only a more detailed explanation of the previous “to them”? Only a resumption of the first dative? Obviously, the author wants the latter to be assumed, but in his uncertainty and the fear of his invention, he has made a mistake and, through the inserted “but,” has created the appearance of a difference, the separation of the influential from the preceding “to them.”

*) Ch 2:2 ἀνεθέμην αὐτοῖς τὸ εὐαγγέλιον . . . κατ᾽ ἰδίαν δὲ τοῖς δοκοῦσιν

The confusion increases. “Even Titus, who was with me, though he was a Greek, was not compelled to be circumcised” – not even Titus? The Greek? So if he was not a Greek, he could have been subject to compulsion? As if that were possible! As if a foreskin, the circumcised one, could still be forced to be circumcised!

18

The sentence is wrongly introduced, but even more unfortunately carried out. If Titus was not forced to be circumcised, was the concession at all rejected, or did he submit voluntarily? The following phrase, “but because of the false brothers who had infiltrated,” *) starts an attempt at redirection, which could only lead to the result: “He was not forced, but because of those false brothers who had infiltrated to spy out our freedom that we have in Jesus Christ,” I gave in — but the sentence introduced with “but” doesn’t even have a verb, and in the concluding sentence that connects with the false brothers through the relative pronoun, the apostle affirms, according to the usual reading, on the contrary: “to whom we did not yield in submission even for a moment.” **) The context, the consistent tendency that the apostle pursues in this context, his endeavor to present himself as entirely independent from the original apostles, the further reason that he gives for his behavior in the same sentence, “so that the truth of the gospel might be preserved for you” – all this certainly justifies the expectation that the apostle will affirm his firm steadfastness against the demands of the Jewish-minded ones. This should make us take a position against the authority of Irenaeus, who reads the sentence “to whom I yielded” without negation, and of Ambrose, who only notes that the Greeks have the negation, but is against it himself.

*) v 4 διὰ δὲ τοὺς . . .

**) οἷς οὐδὲ πρὸς ὥραν . . .

19

However, even if we follow the common reading and read the negation, the sentence still lacks coherence and the disappointment remains that the expectation raised by the “aber” in the parenthetical clause is not satisfied. The phrase “wegen der falschen Brüder aber” (“because of the false brothers, however”) was only possible if the apostle wanted to speak of a conceded point; as for the reason why he acted as he did, to preserve the gospel for the Gentiles in general, could this reason not still remain even if he gave in on this individual case? Could he not hope that by giving in momentarily, he could save the principle of freedom in general? And if he immediately continues in verse 6, “But from those who were recognized as important (what they once were makes no difference to me), God shows no favoritism” and shows how the pillar apostles had to acknowledge his authority as an apostle to the Gentiles and how he even opposed Peter once – does not this transition look exactly like it is about preventing the nightmarish consequences that could be drawn from a momentary concession?

So let the negation fall! The apostle gave in on an individual case! But did he give in because of the false brothers who had infiltrated? Because of false people who were lurking for his freedom – a freedom that did not belong to him alone and which he should have defended with all his might? Instead of fighting, he humiliated himself before malicious observers while he otherwise jealously guarded his independence, asserted it against the apostles, and even brilliantly maintained it in his rift with Peter.

20

Well then, let the negation remain! Yes, let the diversion that is initiated in the parenthetical clause by the stubborn “but” also be taken into account! Both at the same time! Titus was not forced to be circumcised, but I had him circumcised for the sake of the false brothers, although I did not give in to them for a moment in complete obedience (rather, I did not acknowledge or permit the general necessity of circumcision for all Gentile Christians).

But then he would have done rather what he expressly denies, he would have given up his principle in a moment *), and would not even have written to the Galatians about the main thing, that he had defended and asserted the general freedom of the Gentile Christians. The artificial emphasis on “forced” and “obedience” could not replace this assertion, which must not be lacking.

The sentence will never become clear, because the author felt uncertain, did not dare to carry out the preparations he had made, (he did not even allow himself a verb in the parenthetical clause about the false brothers because of his fear) and because he did not know at the end whether to let Titus’ circumcision become a reality or how to secure the apostle’s freedom.

*) πρὸς ὥραν

21

The sentence is a monster because the author, in his various intentions and tendencies, became confused and could not find a way out of the labyrinth of difficulties he had created for himself. It is most likely that he wrote the negation at the end of the sentence, but weighed down by the assumptions he had presented at the beginning, he was not able to secure and depict the apostle’s independence in a clear and vivid manner, as he preserved his and the Gentiles’ freedom in this unclear and confused collision.

The collision was flawed from the outset – to such an extent that a pure and structured resolution was impossible. Only a group of false brethren who had surreptitiously infiltrated themselves to investigate Paul’s freedom had caused the collision? What nonsense! Rather, the subsequent negotiations between Paul and the pillars of the church were based on the assumption that everything in Jerusalem was under circumcision and that the gospel of circumcision prevailed!

Those false brethren had sneaked in secretly? They wanted to investigate Paul’s freedom? Here, in Jewish-Christian Jerusalem, where the contrasts were clear and open as soon as Paul approached the pillars of the church? Secret hostility, lurking malice was necessary to discover Paul’s freedom? Here, where there was a decided and opposing position towards the Gentile apostle and his freedom?

Impossible! The author himself refuted the assumption that created the monster of his confused sentence and thus brought this sentence to its deserved end.

The author, unable to shape his narrative, forgets himself so much that in the same moment in which the apostle explains the neutrality agreement he had concluded with the apostles under handshake, he lets him speak with irritated contempt for the latter. The opportunity for such a heated allusion to the supposed insignificance of the apostles was so unnatural, the author himself had such an unclear understanding of their historical position, that he feels compelled to keep his narrative in suspense on purpose. When he says, for example, “but concerning those who are considered important” (verse 6), he leaves it indefinite whether they themselves believed they were important,*) or whether, as in verse 9 where they are regarded by others as pillars, they were regarded as special by others. When he continues, “whatever they were makes no difference to me,” he leaves it indefinite what they were in the end and in fact. But let us leave him his deliberate vagueness and his uncertainty, and take instead his involuntary “once were” as a betraying witness of his late position, on which he has inadvertently placed the apostle and on which he now lets him speak of the three pillars, Peter, James and John, as men who have long since died. Let us also take the way he initially (verse 2), before the more specific specifications follow (verses 6 and 9), designates the apostles with a lost catchword as the “apparent,” **) supposed to be. He has in mind the passage from the second letter to the Corinthians where the author of the same designates the apostles as the “super-apostles,” *) he initially (verse 2) attaches to the given formula, becomes more specific in verse 6, and finally dares to develop the ironic designation of the apostles in his own way in verse 9.

*) ἀπὸ δὲ τῶν δοκούντων εἶναί τι _ ὁποῖοί ποτε ἦσαν

**) v. 2 δοκοῦντες

*) 2 Cor 11:5 οι ὑπερλίαν ἀποστόλοὶ “but the chief apostle”

23

The idea that the Gentiles were assigned to Paul and the Jews to the Pillar Apostles is too mechanical and even impossible, since it would have been impossible for Paul to only address the Gentiles and leave the Jews aside. The author loses himself in an equally mechanical separation, like the composer of the Acts of the Apostles, only that he separates the Gentile apostle from contact with the Jews, while the latter only sends him to the Gentiles when his gospel has been offered to the Jews in vain. The mechanism of the author of the Galatians shatters against the historical fact that the Jews and their proselytes in Asia Minor, Greece, and Rome were an essential element of the community from the beginning. This original mixture of the Jewish and Gentile elements – (only later, when the views of the New Testament documents about the genesis of Christianity have undergone complete criticism, can we come to the representation of the fermentation that arose from the penetration of those two elements and had as a consequence the formation of the Christian view) – this chemical process that put both elements in tension and produced a new form of historical consciousness from their fusion, at the same time, refutes the mechanism of the Acts of the Apostles.

24

The supposed Paul is finally in Antioch and resists Peter (v. 11) when he came there face to face “because he was in the wrong.” So “because”? *) He only openly opposed him because others had already condemned his hypocrisy as wrong? He wouldn’t have done it if others hadn’t already passed such a strict judgment? This explanatory parenthetical clause is therefore an excessive and floating overflow of the whole thing – it is absurd since Peter’s hypocrisy was an obvious fact and clearly evident to all.

*) ὅτι

The author also keeps his account floating in the statement of the motive that (v. 12) caused the Judean apostle, who initially had communion with the Gentiles in Antioch, to withdraw in fear – “some came from James” – the author dares not specify whether they were official emissaries or just people from his surroundings.

“The rest of the Jews,” who (v. 13) were with Peter until then, “acted hypocritically with him” – so he was a hypocrite? The Judeans were hypocrites when they denied their better conviction for a moment out of fear of James’ people? His principles, their principles were entirely free – freedom was their essence, and only the fear of James caused them to falter for a moment? Impossible! Peter had just been in agreement with Jerusalem and had concluded the division treaty that assigned the Gentiles to Paul alone and reserved the Judeans for the pillar apostles – Paul had just been standing alone against Jerusalem, and his freedom had been his personal privilege until then – Peter was one with Jerusalem and here, in the holy city, everything was unfree, and the biased view prevailed that one did not want to have anything to do with the Gentiles personally – so where does Peter’s freedom and his difference from James and Jerusalem suddenly come from? The author cannot say; he has initiated the collision that is supposed to give rise to the Heidenapostel’s exposition of his principle falsely and unsuccessfully.

25

The unfortunate mistake of the author leads him to become so confused that he even forgets the initial starting point when he forms the introduction of Paul’s rebuke: “If you, being a Jew, live like the Gentiles and not like the Jews, why do you compel the Gentiles to live like Jews?” But is Peter living like a Gentile? Is he not dependent on Jerusalem and James? What was Peter’s offense? Was he trying to force the Gentiles to live like Jews? Was it not rather just about him? His wavering? His personal behavior, that he denied his better conviction for his person? And if his example had consequences for others as well, was it not just for the Jews who, also being carried away by his conduct, forgot their freedom for themselves and did not think of subjecting the Gentiles to Judaism?

The author forgets all the assumptions he has made so far, even the situation in which he has just placed the Jewish apostle Peter, only to bring about Paul’s accusation, rebuke, and exposition, when he worked out this accusation. Peter’s person and behavior were only a means for him to introduce the dogmatic exposition of the Gentile apostle, and as soon as he speaks, that is, as soon as the author gets to the intended topic, the exposition of Christian freedom, he has lost sight of his own, laboriously formed assumptions and even the situation that opened the mouth of the Gentile apostle. Once the Gentile apostle is on his topic, the author does not pay attention to the fact that the long and simply general dogmatic exposition into which he lapses can no longer be considered a rebuke to Peter, and finally, he even forgets that he has given a historical account so far. He does not think to indicate a point where the historical narrative passes into purely dogmatic exposition, and in the end, he knows nothing about having to indicate at least where Paul’s rebuke against Peter ends.

26

We can only note at most that the rebuke of Peter may extend at least or at most – both are the same given the indifference of the following exposition to the assumed occasion – until verse 21, and that the instruction of the Galatians who have turned away begins with the address “O foolish Galatians” in chapter 3, verse 1. However, even with this, we cannot provide this exposition with what it lacks, which is a reference to Peter, it remains what it is – a general, and moreover, very abstract and artificial dogmatic summary of the dialectic of the letter to the Romans and the laboriously cobbled together theme of the subsequent discussion.

————————–

27

The Theme of the Letter

(2: 15-21)

What is the purpose of the failed accusation against Peter that he, who lives as a Gentile, is forcing the Gentiles to live as Jews – what, therefore, is the purpose of this contemptuous reference to Judaism in the new starting point in verse 15: “We, who are Jews by nature, and not sinners from among the Gentiles,” and what is the clumsy concession to the Jewish assumption that the Gentiles are sinners – the affected phrase: “and not sinners from among the Gentiles”?

What is the point of all this? It is meant to prove that the author has clumsily picked up individual keywords from the discussion in the Romans letter about the sinfulness of the Gentiles and the privileged position of the chosen people and used them incorrectly.

Why does the author add verse 16, with its clumsy participle “knowing,” *) to this “we,” followed by the sentence, “that a man is not justified by the works of the law, but only through faith in Jesus Christ”?

*) εἰδότες

Through this reference to established knowledge, through this appeal to common consciousness, he wants to prove to us that on the standpoint on which he stands, the genesis of the dogma is already completed.

Of course, this is not his true intention – he does not know what he is doing and how much he is getting lost – but the fact remains: he puts the dogma, because it is already completed and finished, in front of the deduction that pretends to be still trying to obtain it.

28

He piles almost all the keywords of the dogma together in verses 16 and 17, but he leads them there awkwardly and heaps them so recklessly on top of each other that they lose their original meaning and effect.

Thus, in the parenthetical clause introduced by “knowing” that no one is justified by the works of the law, but only through faith in Jesus Christ, he even overlooks that the qualification “only” *) not only requires the contrast of the impotence of the law, but also the general intermediate link that man, in fact, obtains justification through faith alone.

Furthermore, when he finally picks up the “we” in the sentence “we also have believed in Jesus Christ,” and the thought should progress, he repeats in the sentence “so that we may be justified by faith in Christ and not by works of the law” just what he had already assumed as commonly known in the parenthetical clause.

So much is he dominated by the given categories or rather keywords of the dogma, and dominated externally, that in the moment afterwards, in the added reason, “because no flesh is justified by works of the law,” he only repeats what he had already said twice and still believes that he is making progress in the development and is doing as if he is offering something new.

Then, when he continues in verse 17: “But if, while seeking**) to be justified in Christ, we ourselves *) have also been found to be sinners, is Christ then a servant of sin?” it remains unclear how he arrives at this question and conclusion, which he rejects as false with a “far be it!” Does seeking righteousness in Christ expose and betray people as sinners, thus leading to the false conclusion that Christ is a servant of sin? Or does it lead to this misconception when it should prevent people from being sinners, and when it fails to achieve its goal? Is being a sinner a consequence of striving for true righteousness, or is it something that appears despite this effort in individual cases? Is it a universal natural consequence or a exceptional phenomenon?

*) εἰ γὰρ διὰ

**) ζητοῦντες

*) καὶ αὐτοὶ

29

The author will not tell us why being found as sinners of those striving for righteousness in Christ could lead to the false conclusion that Christ is a sinner-servant, nor will he be able to indicate it to us. He would have to admit that he wanted to reproduce the objections of the Letter to the Romans: “shall we continue in sin that grace may abound?” and “shall we sin because we are not under law but under grace?” But he would also have to admit that he was unable to reproduce and handle this dialectic. He would then also have to admit that he borrowed his “far be it!” from both passages of the Letter to the Romans.**)

**) Rom 6:2, 15 μὴ γένοιτο

30

He borrowed from the Romans the formula for rejecting a conclusion that would be disadvantageous for the Savior, but he did not really reject it. Indeed, the author of the Romans understood thoroughly how to reject the apparent consequences of his dialectic and he did reject them after his exclamation “God forbid!” On the other hand, when the author of the Galatians *) continues in verse 18, “For if I rebuild what I tore down, I prove myself to be a transgressor,” in order to reject that conclusion, he assumes an object that was not even mentioned in the previous draft – the law! – He must also leave it unexplained why being found as a sinner for those who seek true righteousness is rebuilding the law – if he cannot explain it, why should this seemingly incompatible being found as a sinner among the believers and rebuilding the law lead to the objection he wants to refute? From the disharmony of completely foreign tones, no harmony can emerge – thoughts that lack any middle term cannot be subjected to a higher unifying fundamental idea – one who misunderstands the dialectic of Romans from the beginning cannot reproduce the final solution.

*) Since the author does not introduce us to any real dialectic, creates nothing new, and only picks up catchphrases, he cannot motivate us to set his work in detailed opposition to the dialectic of the Romans.

When the author then continues in verse 19: “For I through the law am dead to the law, that I might live unto God. I am crucified with Christ”, he wants to justify the unnatural supposition that preceded it: that it is impossible for the believer to present himself as a transgressor by rebuilding what has been dissolved. He wants to say, “for” the believer, but a pure connection to the previous confused sentences is impossible from the outset, and in the end, the author had to leave unexplained why rebuilding what has been dissolved would expose the believer as a transgressor and as what kind of transgressor. It is therefore no wonder that even the current sentence falls apart. Since the author’s main purpose was to refute the false conclusion that Christ is a sinner, how does he come to the argument that the believer is dead to the law? Why does he separate, in the most disturbing way, the sentence “I am crucified with Christ” from the explanation of the common crucifixion with Christ? Why does he create the impression that the sentence about the believer’s death to the law receives its conclusion from the purpose determination “that I might live unto God”? Why does he add the determination of the common crucifixion in such a dragging way?

31

He copied the Letter to the Romans but did not understand it. He rejects the objection whether we should continue in sin so that grace may abound, by saying that the believer has died to sin and specifically died as a companion of Christ’s death (Romans 6:2-11) – he also speaks of being dead to the law – but he also knows, as the original creator, what the means of this consequential dying is – it is not the law, but the body, namely the death of the Redeemer.*) Finally, he comes to the conclusion that those who have died with Christ to sin “live to God,” and those who have died through the body of Christ to the law belong to another, namely the risen Christ.**) From this order of exposition, the author of the Letter to the Galatians has created his confusion. And when he picks up the idea of new life in verse 20 in a new antithesis: “So now it is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me,” and then immediately varies the same thought and lets the explanation run into a lengthy participial construction, “but now the life I live in the flesh (!) I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me,” he only proves by this overfilling and awkward expansion of the exposition that he did not want to abandon the parallel that the Second Letter to the Corinthians offered to the Letter to the Romans.***)

*) Rom 7:4 ἐθανατώθητε τῶ νόμῳ διὰ τοῦ σώματος τοῦ χριστοῦ

Rom 6:2 ἀπεθάνομεν τῇ ἁμαρτίᾳ

Rom 6:4 συνετάφημεν αὐτῶ (χριστω).

Gal 2:19 διὰ νόμου νόμῳ ἀπέθανον . . . . χριστῶ συνεσταύρωμαι

**) Rom 6:11 νεκροὺς μὲν . . . . τῇ ἁμαρτίᾳ ζῶντας δὲ τῶ θεῶ

Rom 7:4 ἐθανατώθητε τῶ νόμῳ . . . . . εἰς τὸ γενέσθαι ὑμᾶς ἑτέρῳ

Gal 2:19 ἵνα θεῶ ζήσω

***) 2 Cor 5:15 εἷ εἷς ὑπὲρ πάντων ἀπέθανεν ἵνα οἱ ζῶντες μηκέτι ἑαυτοῖς ζῶσιν ἀλλὰ τῶ ὑπὲρ αὐτῶν ἀποθανόντι καὶ ἐγερθέντι.

Gal 2:20 ὃ δὲ νῦν ζῶ ἐν σαρκί, ἐν πίστει ζῶ τῇ τοῦ υἱοῦ τοῦ θεοῦ τοῦ ἀγαπήσαντός με καὶ παραδόντος ἑαυτὸν ὑπὲρ ἐμοῦ

33

After the author has, as far as he could with the help of the keywords from the Book of Romans, completed his jumbled work of not really introducing any dialectic – what dialectic? The dialectic between sin and grace? Between law and grace? Between death and life? No! – he proceeds in verse 21 with the unsuitable transition: “I do not reject the grace of God” – (as if he had been accused of such rejection!) – and returns to the topic: “For if righteousness comes by the law, then Christ died in vain,” and proceeds to explain the same.

Let us see if the explanation is more successful than the introduction of the topic.

The Dogmatic Discussion

(3: 1 – 4: 31)

The beginning is far from fortunate. It is affected when the author, in Galatians 3:1, wonders who could have bewitched the Galatians, as Jesus Christ had been “clearly portrayed” before their eyes, and overloaded when he emphasizes the clarity and vividness of the image with the dragging qualification “as if he had been crucified among you.” One was enough: “before your eyes” or “among you.”

With the question in verse 2, “I want to ask only this of you: did you receive the Spirit by works of the law or by hearing with faith?” he wants to throw out the threads of the exposition, i.e., to determine the keywords of the following discussion. Unfortunately, with this question, he also sets up an assumption that he must retract immediately afterward, something he himself had accomplished a moment before (verse 1). He assumes that the Galatians, who had just been accused of turning away from God and the truth, possess the Spirit. In the following verses (verse 5), he builds his argumentation on the basis of this assumption. Yet, he is compelled to retract this assumption completely immediately afterward, just as he is about to build on it, admitting in verse 3 that the Galatians “began in the Spirit but are now ending in the flesh.”

34

The deadly confusion arises from the fact that he really only wants to instruct the believers in general, that he is actually speaking to the entire church, and after he has linked up with the believers’ own consciousness of the Spirit, he remembers the fictitious assumption that the apostle is writing to apostates, spiritless servants of the law. He feels that he has gone astray and believes he can make everything right again by characterizing the Galatians as what they are supposed to be according to the original assumption of the letter in a couple of interjections (v. 3 and 4).

However, even in this correction, he has made a mistake. His punishing question, “Have you suffered so much for nothing?” presupposes a long series of trials, sufferings, and martyrdoms – but the first entrance of the letter (C. 1, 0) presupposes that only a short period of time had elapsed between the conversion of the Galatians and their apostasy. Moreover, to his detriment, the author, in order to become familiar with this particularity, continues quite artificially: “if only it were for nothing” – he acts as if he knows something worse for which the Galatians could have suffered for their trials – he acts as if he could continue the construction so that the Galatians’ trials and martyrdoms not only were in vain but also turned out to be harmful to them – in fact, however, he has only lost his way, and the construction could not be continued in this way – it was already to the detriment of the Galatians if all their trials and sufferings were in vain.

35

Furthermore, in this new section, he also incorporates keywords from the Romans letter. The phrase “hearing of faith,” from which the Galatians are said to have received the Spirit according to verse 2, is itself an unclear combination and only understandable for someone who remembers that according to Romans 10:17, faith comes from hearing – (according to the context of the Romans passage, from the preached word).*) When the author then picks up his argumentation from the possession of the Spirit in verse 5 and without any reason or basis – (the context of the argument even rejects this excess as a disturbing addition) – refers to the one who “supplies the Spirit” as the one who also worked miracles among the Galatians, only the passages from the Romans and 2 Corinthians letters, according to which Christ worked miracles through the apostle by the power of signs and the power of the Spirit, and the apostles worked the signs of an apostle among the Corinthians in miracles*), are to blame for this unnecessary and inappropriate overloading.

*) Rom 10:17 ἡ πίστις ἐξ ἀκοῆς

Gal 3:2 ἐξ ἀκοῆς πίστεως

*) Rom 15:18-19 κατειργάσατο χριστὸς δι᾽ ἐμοῦ . . . ἐν δυνάμει πνεύματος θεοῦ

2 Cor 12:12 τὰ μὲν σημεῖα τοι ἀποστόλου κατειργάσθη ἐν ὑμῖν . . . ἐν . . . δυνάμεσι.

Gal 3:5 ἐνεργῶν δυνάμεις ἐν ὑμῖν

36

God is the subject with which the author accomplishes the return to his topic – it is God who, in those two participles that represent the place of the subject, bestows the Spirit and works miracles – but what is it that this God does? The author does not say, the verb is missing, but he could not find a suitable one because he has connected the keywords “from works of the law or from hearing with faith,” which originally presuppose the receiving person as the subject in the Romans letter, inconveniently enough with God as the active and giving subject. It was impossible for him to indicate in a specific verb what this God does “from works of the law or from hearing with faith” – he is well aware that the resumption of the determinations of those participles in a verb would not be enough and that old ways of power and grace of the God whom the Romans letter opposes to man in his sin, powerlessness, and faith must follow – but to list all the revelations of this God one by one was too much for him – he would rather leave out the verb.

That it was a mistake on his part to make God the subject in this botched sentence, he proves himself when he immediately proceeds and rather aphoristically continues (v. 6), “as Abraham believed God and it was counted to him as righteousness” – that’s right! The subject had to be man in the previous sentence! The disharmony of that unfortunate sentence now becomes all the greater, especially with the “as” – “as Abraham believed” – which is referred to an explanation and conclusion that is not given. This “as” *) stands therefore unsupported there since the previous sentence did not even have a verb, and the question it contained was not answered. All these verbs, especially the verbs that indicate the position of the believer, are certainly known to the author from the Romans letter – in the same letter (Romans 4:1-5) Abraham’s position is also extensively developed – and what is known and familiar to him, the author believes he only needs to remind the readers of with a few keywords.

*) καθὼς

37

“Therefore, you see**),” continues the author in verse 7, “that those who are of faith are the sons of Abraham.” But how are his readers supposed to see this? He has not provided anything on which his “therefore” could be based. He is completely certain of his argument and fully expects his readers to understand the conclusion and the result – and yet he has not provided a single intermediate link in the proof, nor even hinted that Abraham’s offspring is universal and spiritual. He believes that because he has the proof before his eyes, he can also demand that his readers draw the final conclusion – he has in mind the argumentation in Rom. 4:11-25 and confuses his own situation and that of his readers, for whom these dogmatic arguments are familiar and commonplace, with the fictional assumption that the apostle is creating and developing these concepts and proofs. Reality undermines and confuses the fiction.

**) γινώσκετε ἄρα

38

Afterwards (V. 8-9), he only cites a few keywords from the Epistle to the Romans to support his argument about the universality of Abraham’s descendants. At least he realizes that the “therefore” in verse 7 was not justified by the preceding argument and tries to make up for it by providing the necessary information for the conclusion.

However, the following statement that those who are “of the works of the law” are under a curse is missing nothing more and nothing less than the main point that no one can keep the law – precisely the main issue that the author has difficulty understanding and which is explained in various ways in the Epistle to the Romans.

He only provides one of these explanations from the Epistle to the Romans in verse 11, and cites it as evidence that “no one is justified before God by the law.” But why is this evident? Is it evident from the nature of the law? From human nature? From experience? No! Only because he can borrow a few keywords from the Epistle to the Romans*). He tries to provide his own explanation – “the righteous shall live by faith” – but this is not a proof, it is just a tautology, as both the fact that faith gives life and that the law does not justify are fundamentally the same statement and both require proof.

*) Rom 3:20 διότι ἐξ ἔργων νόμου οὐ δικαιωθήσεται πᾶσα σὰρξ ἐνώπιον αὐτοῦ

Gal 3:11 ὅτι δὲ ἐν νόμῳ οὐδεὶς δικαιοῦται παρὰ τῶ θεῶ

39

The author wants to prove something, but he is unable to do so and repeats his previous statements — he wants to exhaust the topic but only provides scattered quotes from the Romans letter.

Thus, in verse 12, he makes a new attempt by stating that “the law is not based on faith; on the contrary, it says, ‘The person who does these things will live by them.'”*) However, he only hastily and disorderly copies the antithesis of the Romans letter (chapter 4, verses 4-6), in which the righteousness of faith and that of the law are actually set in opposition, and the majority, which takes the place of the law – (“the person who does them”) – is not disturbed and is naturally motivated, since it belongs to the citation from Leviticus, which speaks of the commandments of the law.**)

*) ὁ ποιήσας αὐτὰ …. ζήσεται ἐν αὐτοῖς

**) Rom 10:5 [corrected from 5:10] Μωϊσῆς γὰρ γράφει τὴν δικαιοσύνην τὴν ἐκ τοῦ νόμου, ὅτι ὁ ποιήσας αὐτὰ . . . .

After the author (in verse 13) describes redemption as liberation from the curse of the law, without having previously shown why the law is a curse – and after he clumsily describes in verse 14 the purpose of this redemption as the transfer of Abraham’s blessing to the Gentiles and the receipt of the promise of the Spirit – he suddenly, only because he has just spoken of the promise, inserts the parenthetical statement in verse 16 that the seed mentioned in the promise to Abraham could only be Christ – and finally, in verses 17 and 18, he comes to the laborious and tedious thought that the law, which only came after the promise, could not annul or overthrow the promise. He reproduces the idea of the Romans letter (chapter 4, verses 10 and 13) that the promise came to Abraham independently of circumcision and that he was justified before being circumcised.

40

The author intends to arrive at the discussion of the purpose of the law in the Book of Romans with all of this. He asks in verse 19, “Why then the law?” and answers, “It was added because of transgressions.”*) However, he cannot answer the question posed by commentators whether this means to restrain or to increase transgressions. He must leave the matter in a dangerous state of ambiguity because he did not understand how to express the dialectic of the Book of Romans concerning the relationship between the law and sin. Furthermore, he even greatly erred in his expression. According to the Book of Romans, the law is an intermediate work that came before grace to make sin increase so that grace would abound.**) Its purpose is to make sin come to life and exist as sin, because “apart from the law, sin lies dead”***) (Romans 7:8). This is real dialectic truly executed by the author of the Book of Romans, and it could have been thoroughly and truly executed by him. The reason for this mistake is that the author used one phrase of the Book of Romans: “where there is no law, there is no transgression”*) (Romans 4:15) – a phrase that still holds true with the necessary caution – incorrectly and processed it into his main thesis.

*) τῶν παραβάσεων χάριν προσετέθη

**) Rom 5:20 παρεισῆλθεν ἵνα πλεονάσῃ τὸ παράπτωμα

***) ἁμαρτία

*) Rom 4:15 οὖ γὰρ οὐκ ἔστιν νόμος, οὐδὲ παράβασις

41

The following remark about the mediator of the law (V. 19-20), which has given rise to countless explanations, but which is completely clear if one does not expect more from the author and his art of presentation than what his other performance justifies, contains a new turn and yet, despite its independence, is linked to the preceding allusion from the Romans through a participle, “ordained through angels,” and this participial clause**), whose subject is “the law,” is even overloaded in a cumbersome and pointless way by the mention of angels: “ordained through angels,” etc.

**) διαταγεὶς

The idea that angels served in the giving of the law is a notion that has forced itself untimely on the author here*) – he actually only wanted to get to the word “mediator” in order to attach a remark to it that sheds a new light on the superiority of the Gospel over the law. The following verse (20), which has caused so much trouble for interpreters: “Now a mediator is not a mediator of one, but God is one,” is based on the assumption that Moses is only a mediator, and deduces from this the weakness of his position. He stands between two parties, receives and gives – he received the law (through the angels) from God, and now it depends on what man does with what he receives through him. The ultimate result therefore depends on the behavior of man, and according to the author’s opinion, it can be easily calculated given the weakness of man – in other words, the law is a contract whose duration, among other things, depends on whether one of the contracting parties, man, holds and observes it. While, therefore, the mediator depends not only on one, but especially on man, God is only one, i.e. dependent only on Himself, follows only Himself and His self-consistent plan – acts purely and solely according to His plan and His (unchanging) nature – while the law has the weakness of a contract, the promise is unchangeably established since it depends only on one – God, who is one.

*) She also finds herself in Apollo. history 7, 53.

Heb. 2, 2. We shall not yet decide here on the relation of these passages to the parallel of Galatians.

42

The author, as if this new turn of thought did not occur and by its complete execution did not push back the previous reference to the Romans, immediately connects to it with the formula “so”,*) as if this reference were still fresh in everyone’s mind, in verse 21 and asks: “Is the law then against the promises of God?” In indicating the purpose of the law, he wants to get to the statement in the Nömerbrief that God has enclosed all under disobedience, and he understands it only insofar as he has to transform the subject of his original into scripture and leave the relationship of this subject to the law indeterminate, so that it is unclear whether scripture itself is the law or the general statement that contains the law.**)

*) οὗν

**) Rom 11:32 συνέκλεισεν γὰρ ὁ θεὸς τοὺς πάντας εἰς ἀπείθειαν ἵνα

Gal 3:22 ἀλλὰ συνέκλεισεν ἡ γραφὴ τὰ πάντα ὑπὸ ἁμαρτίαν ἵνα

43

So dependent is he, however, on his source that he also designates the proof of grace as the purpose of this inclusion of all under sin, albeit not with the same precision as the Epistle to the Romans: “For God has consigned all to disobedience, that he may have mercy on all,” says the Romans, while our author says, in a more verbose and less elegant manner, “so that the promise might be given to those who believe in Jesus Christ through faith.”

But before the compiler answers the question of the purpose of the law according to the guidance of the Epistle to the Romans, he inserts a sentence in verse 21 between the question and the answer that gives the appearance of his wanting to solve the matter himself: “For if a law had been given that could give life, then righteousness would indeed be by the law.” The compiler, who does not create categories but also cannot handle them correctly and mixes them up wildly, has erred in this overloading. There was no mention of a law having the power to give life, and there was no reason whatsoever for the objection “For if the law had this power.” The only question was whether the law now contradicts the promise. Nobody had thought about this in the immediate previous discussion, and nobody could have thought that the law possessed the power of life. Therefore, there is nowhere any reason for the author’s defensive argumentation. However, one thing has long been on his mind, one thing he has not yet accomplished, despite several attempts and efforts: he has not been able to make it clear that the law carries in itself and in the dichotomy it presupposes and which forms its basic condition, the impossibility of its execution, and thus the basis of its impotence. And he has clumsily inserted this thought, which still occupies and burdens him, between his plagiarism from the Epistle to the Romans.

44

After he then describes the law as the disciplinarian leading to Christ in verses 23-26, and contrasts the life under the disciplinarian with the present sonship of believers, which he essentially exhausts in thought, he further justifies it with a new turn in verse 27, which led to nothing in the preceding discussion, with an image that completely emerges from the previous circle of thought. The phrase “For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ” is borrowed from the Epistle to the Romans, the image of the following clause “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female” is borrowed from another passage in the same epistle, and a reference that leads him to the first Epistle to the Corinthians moves him here, where there was no question of this contrast, to expound on the idea of the abolition of all previous contrasts according to 1 Corinthians 12:13.

45

However, only in the Romans is there real coherence, and a real and significant idea is carried out when it says in chapter 6, verse 3, “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death?” This statement from Romans is the indispensable link of a real and great exposition. On the other hand, the compiler of the Galatians has made this statement irrelevant by using another passage from Romans, which speaks of putting on Christ, for the latter part of the sentence.*)

*) Rom 6:3 ὅσοι ἐβαπτίσθημεν εἰς χριστὸν ἰησοῦν εἰς τὸν θάνατον αὐτοῦ ἐβαπτίσθημεν

Gal 3:27 ὅσοι εἰς χριστὸν ἐβαπτίσθητε, χριστὸν ἐνεδύσασθε·

Rom 13:14 ἐνδύσασθε τὸν κύριον ἰησοῦν χριστόν

Then, when the author of the First Corinthians, in the context of his exposition on the unity and inner harmony of the ecclesiastical organism, describes baptism as the binding agent of this organism, so that all, Jews and Greeks, slaves and free, form one body, as they are all infused with one spirit, this is again a coherent statement and a thoughtful link in a large and coherent exposition. However, the compiler of the Galatians could not give his plagiarism a firm foundation or support, and added more oppositions, increasing them beyond those whose abolition the First Corinthians spoke of, to include the opposition of male and female, for which there was no place here.

46

Actually, the compilation that the author provided so far should have ended with verse 28, since all the contradictions have now been overcome. But did he really give a living, structured presentation? Did the keywords and fragments belong to him, which he rather borrowed from other works? Did he really develop, draw conclusions, and prove anything? None of all this – therefore it was also impossible for him to calculate the point at which a presentation must come to its conclusion – therefore it also costs him neither effort nor overcoming to add a foreign, superfluous, trailing link to his compilation with verse 29, which he again borrows from the letter to the Romans and then copies verbatim in chapter 4, verse 7, when he gives the presentation he now intends.

He now takes up the section of the letter to the Romans that deals with the godliness of believers in Romans 8:14-17 and receives its conclusion with the conclusion in verse 17: “And if children, then heirs.” Therefore, he says in Galatians 3:29: “And if ye be Christ’s, then are ye Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise.” This fragmentarily thrown sentence leads him to that exposition of the letter to the Romans, and in conclusion, he copies it verbatim: “And if ye be Christ’s, then are ye Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise.”*)

*) Gal 4:7 εἰ δὲ υἱός, καὶ κληρονόμος διὰ θεοῦ

Rom 8:17 εἰ δὲ τέκνα, καὶ κληρονόμοι· κληρονόμοι μὲν θεοῦ . . .

47

Firstly, let us try to help him by transitioning from the confusion of the previous metaphors and oppositions – being held under sin and receiving the promise, being under the guardian and becoming a child of God – to the new metaphor and opposition of the minor and major heirs in Chapter 4, verse 1. He believes that he is in the best possible context, even making the transition with the words: “but I mean”*), thus thinking that he has just spoken about the minor heir who is under guardianship, as well as his low legal status and that his statement, that such a heir does not differ from a servant, is fully prepared – he believes that his readers have been drawn into this deduction to the extent that they are only waiting for the final culmination of it, which lies in the comparison with the servant. However, none of this is the case: there is no context about the minor heir, no deduction leading up to the final point.

*) λέγω δέ

So how can we help the compiler? By allowing him the miracle of connecting to the distant allusion contained in the earlier opposition between living under the guardian and being a child (verse 24-25), which has been pushed back far by new deductions, as if it were immediately before and as if those who live under the guardian and face the children of God are really the children and heirs who stand under guardianship during their minority.

Therefore, we will forgive him and forget with him that so far, childhood has been opposed as a gain of the subordinate standing, which preceded faith – meaning, we will allow him to do so and assume that so far the opposition has been only the difference in status between the children.

48

We will also forgive him that the image of the heir who, during his minority, is under guardianship, limps significantly, as God the Father is and remains alive.

Finally, however, the confusion becomes so great and the compiler reveals himself to such an extent that he can no longer be helped and his work collapses.

While in the beginning of this new deduction the heirs are assumed to be children even during their minority, they become children only at the end (verse 5-7) and receive sonship through Christ.

And when they become children and receive sonship at the end of this deduction, the contrast between minority and adulthood is no longer considered – in fact, their elevation to heirs is only described as a consequence of their elevation to the new status of children (verse 7).

In short, the conclusion of the deduction denies the beginning, knows nothing of it, and the whole thing has long since fallen apart, while the compiler still thinks he is in the best context. The confusion even rises to the point that the author, at the very moment when he describes sonship (verse 5) as a gift, describes this gift (verse 6), which he also describes in changing, unclear forms, as the necessary consequence of the fact that the recipients are children from the beginning.*)

*) V. 6 ὅτι δέ ἐστε υἱοί

49

This exposition had to end so unfortunately after the compiler had forced his image of the mature and immature heir who does not differ from the servant into the clear work of the Romans (8:14-17), in which the state of servitude and sonship are opposed to each other. The dissonance with which he ended was so glaring that he ultimately had to resort to almost verbatim copying the work of the Romans, thereby having to designate the elevation of the believers to heirs as a consequence of the received sonship, and forgetting that according to his assumption, they were already children and heirs, albeit immature.

Moreover, the more literally he copied, the more he betrayed his lack of skill. When the author of the Romans says (8:15), “you have received the spirit of adoption, whereby we cry, Abba, Father,” it is clear and exhaustive. Our compiler, however, who wanted to appear rich with his collected dogmatic formulas, has crammed a whole representation of the work of redemption into this exposition on the state of children and heirs, and therefore brings the keyword of sonship into the sentence (v. 5) that the Son of God redeemed those under the law “that we might receive the adoption of sons.” Therefore, when he speaks of the spirit that testifies in the hearts of believers about their sonship, he must create a new formula, and thus he creates that excessively overloaded sentence (v. 6): “And because ye are sons, God hath sent forth the Spirit of his Son into your hearts, crying, Abba, Father.”

The rich man who gave readers of this exposition on the state of sons and heirs a whole representation of the work of redemption as an addition on top of it all had no room in the narrow space in which he had to cram this representation to even suggest how the redemption happened and what it consisted of. Or should the preceding participle (v. 4), according to which Christ came under the law*), have been the means of this redemption? Then he had neither room nor time to explain why this means was effective and expedient, why it was necessary.

*) γενόμενον ὑπὸ νόμον

————————–

50

After the long dogmatic argument that has kept the author occupied until now, he finally returns to a personal address to the Galatians and wonders anew about their relapse into the law (V. 8, 9)**), while just a moment ago he was assuming that he was speaking to those who have “lived under the law” (Ch 4:5), in other words, to Jews. And while he now describes their lapse into the law as a relapse, he addresses his readers as Gentiles who “did not know God and served gods that were not really gods” – in other words, he confuses two assumptions, which would not have been possible for a man who was really writing to his former pupils.

**) πῶς ἐπιστρέφετε πάλιν

For how long must Judaism have fallen, finally, if its nature could be placed alongside heathenism as one of the elemental principles of the world*, due to its dependence on natural determinations!

*) V. 3 στοιχεῖα τοῦ κόσμου. V. 9 στοιχεῖα.

51

The author continues his personal discussion with the Galatians: “he fears for them (v. 11) that he may have worked in vain,” just as the author of the second letter to the Corinthians fears that his readers have been led astray from simplicity in Christ.**)

**) 2 Cor 11:3 φοβοῦμαι δὲ μή πως,

Gal 4:11 φοβοῦμαι ὑμᾶς, μή πως

He then asks his readers in verse 12: “become like me, because I have become like you, brothers, I beg you.” But he does not say in what way he has become like them. Has he become free from the ordinances? Given himself wholly to God? Impossible! He descended to them — so they should ascend to him. Should they then become like him, just as he became like them by abandoning Jewish customs and identifying with them as Gentiles? Again, impossible! The context leads to no real point of comparison — none is even hinted at, and the last point, which would hold up the apostle as an example of temporary humility, cannot be sustained precisely because the apostle is to be presented as a real, enduring ideal. The author wanted to present him as an ideal, but did not understand how to work out his intention, and did not dare to copy his original – (1 Corinthians 11:1) “Follow my example, as I follow the example of Christ” – directly. ***) The conclusion of this plea: “Brothers, I beg you, you have not done me wrong” is a disconnected babble, for which the author gives no hint of explanation and which leads him to describe the extraordinary joy with which the Galatians received the apostle during his first visit in verses 13-15.

***) 1 Cor 11:1 μιμηταί μου γίνεσθε, καθὼς κἀγὼ χριστοῦ

Gal 4:12 γίνεσθε ὡς ἐγώ, ὅτι κἀγὼ ὡς ὑμεῖς, ἀδελφοί, δέομαι ὑμῶν.

1 Cor 4:16 παρακαλῶ οὗν ὑμᾶς, μιμηταί μου γίνεσθε

52

Did the author visit the Galatians more than once? The author doesn’t mention a second visit that corresponds to the first one. He betrays his underlying assumption that, when he wrote the letter, the Apostle had only been to the Galatians once.*) Immediately after describing his supposed first visit (Galatians 4:14-15), he says in verse 16, “Have I now become your enemy by telling you the truth?” This means that he assumes that the change in their attitude toward him occurred between then and his first visit, which he considers to be the only one and which he doesn’t mention again. The word “now” in Galatians 3:3, “Having begun by the Spirit, are you now being perfected by the flesh?” also assumes only one visit by Paul among the Galatians and implies that the change in their attitude toward him happened quickly after their conversion. The author indicates that the transformation occurred so rapidly that the Apostle himself was surprised, making it impossible for him to have made a second visit between the Galatians’ conversion, their falling away, and the writing of the letter.

*) Not το δεύτερον, which corresponds to the ο πρώτον

53

How did the author come to describe his only presence among the Galatians as the first, suggesting that there was a second one? Or did he realize his mistake? Did he hope to correct it when he said later in verse 20: “I would like to be with you now”, that is, when he expressed his wish as a definite intention?*). Did he hope that his wish would count as an action and that his only presence among the Galatians would be counted as the first one?

*) “He says not: I would like to, not:” ἤθελον ἀν, but I wanted to, ἤθελον.

Anything was possible for him – but it is certain that this formula: “I would like to be with you now”, is a copy of the formula in the Second Corinthians: “I am ready to come to you for the third time”**), and that only the dependence of the author on this letter, which speaks of a repeated presence of the apostle among the Corinthians, led him to use a formula – “the first time” – which suggests a second presence of the same person among the Galatians.

**) 2 Cor 12:14 τρίτον ἑτοίμως ἔχω ἐλθεῖν πρὸς ὑμᾶς.

Gal 4:20 ἤθελον δὲ παρεῖναι πρὸς ὑμᾶς ἄρτι,

Furthermore, when he characterizes that first presence among the Galatians (chapter 4, verse 13) as one in which he preached “in the weakness of the flesh,” it would be impossible for him to say a clear word about what this weakness of the flesh consisted of and how it manifested itself, whether it was the same as the “temptation in the flesh” of which he speaks immediately afterwards (verse 14), and what should be understood by this temptation. He does not know, does not need to say, and leaves the closer determination to the apostle of the Corinthians, who (2 Corinthians 11:30) boasted of his weakness, whose flesh (2 Corinthians 7:5) was of no use to him in his distress, and who also suffered “in weakness, with much fear and trembling”*) among the Corinthians.

*) 1 Cor 2:3 ἐν ἀσθενείᾳ καὶ ἐν φόβῳ καὶ ἐν τρόμῳ πολλῶ

Gal 4:13-14 δι᾽ ἀσθένειαν τῆς σαρκὸς …. πειρασμὸν μου τὸν ἐν τῇ σαρκί μου

54

The author must leave it indefinite in what consisted the weakness of the flesh in which the apostle preached to the Galatians, but the definiteness that he (V. 14-15) lends to the devotion with which the latter received the apostle is so exaggerated that it betrays itself as an artificial fabrication by its vividness and artificiality. “You received me as an angel of God – as Christ Jesus” – what a chilly exaggeration! “You would have plucked out your own eyes and given them to me, if possible” – if it had been necessary, a man who had really had a personal relationship with the Galatians would have written this – in his icy exaggeration, the author confuses the simplest concepts and does not see that the possibility, if the willingness was not senseless and useless pomp, had to be firmly established.

Suddenly, the author describes the seducers before he even named and introduced them, and after only briefly mentioning “the disturber” in passing at the very beginning of the letter, “they are zealously trying to win you over, he says in verse 17 without specifying the subject, but they want to exclude you so that you will zealously seek them” – but how did he arrive at this “zealously trying to win over”? Where is the preparation for it? Nowhere. Where is the absolutely necessary contrast to the “zealously trying to win over” that is “not fair”? Nowhere, unless in the Second Corinthians, where the author “is zealous for God” for the Corinthians,*) but also really demonstrates this zeal, while the compiler of the Galatians letter even leaves it indefinite about what the false zealots want to “exclude” the Galatians from.

*) 2 Cor 11:2 ζηλῶ γὰρ ὑμᾶς θεοῦ ζήλῳ.

Gal 4:17 ζηλοῦσιν ὑμᾶς οι᾽ καλῶς

55

In the uncertainty of his consciousness, the compiler can only write vaguely, he must keep the matter in suspense. “It’s nice,” he continues in verse 18, “to be eager to do good at all times, and not just when I’m with you” – but what is “doing good”? It is not said. Who should be eagerly doing good? The Galatians? Yes, they must be, since the author had just complained that they were eagerly following false teachings. But what is the following qualification: “not just when I’m present”? Clearly, it is supposed to make Paul the subject! He should indeed be eagerly doing good even in his absence! – how baseless! How affected!

How cumbersome is the exclamation immediately following this desire, “My children, for whom I am again in the pains of childbirth until Christ is formed in you!” – how affected is this imitation of the sentence in the first Corinthians (1 Cor. 4:15): “In Christ Jesus I have begotten you!”

When the compiler comes to that disclosure in verse 20 that he wanted to be present with them “and change his tone,” he again carefully avoids specifying whether this change should be for good or for evil – nor does he give the slightest hint as to whether it should be in contrast to his previous warm relationship with the Galatians or to the language of the entire letter or to the stance of the current passage. He carefully avoids any specificity – he cannot create.

56

After these last uncertainties and vaguenesses, he comes in verse 21, without any transition, without any preparation, to the allegory of Ishmael and Isaac (verses 21-31), which forms the conclusion of his dogmatic exposition and shows the nature of both Testaments through the fate of the son of the bondwoman and the son of the free woman. The author of the Epistle to the Romans had already set Isaac as the son of the promise and the type of the true children of Abraham in contrast to other children of the patriarch (Romans 9:7-9) – our compiler has developed this idea, this time, in a meaningful way.