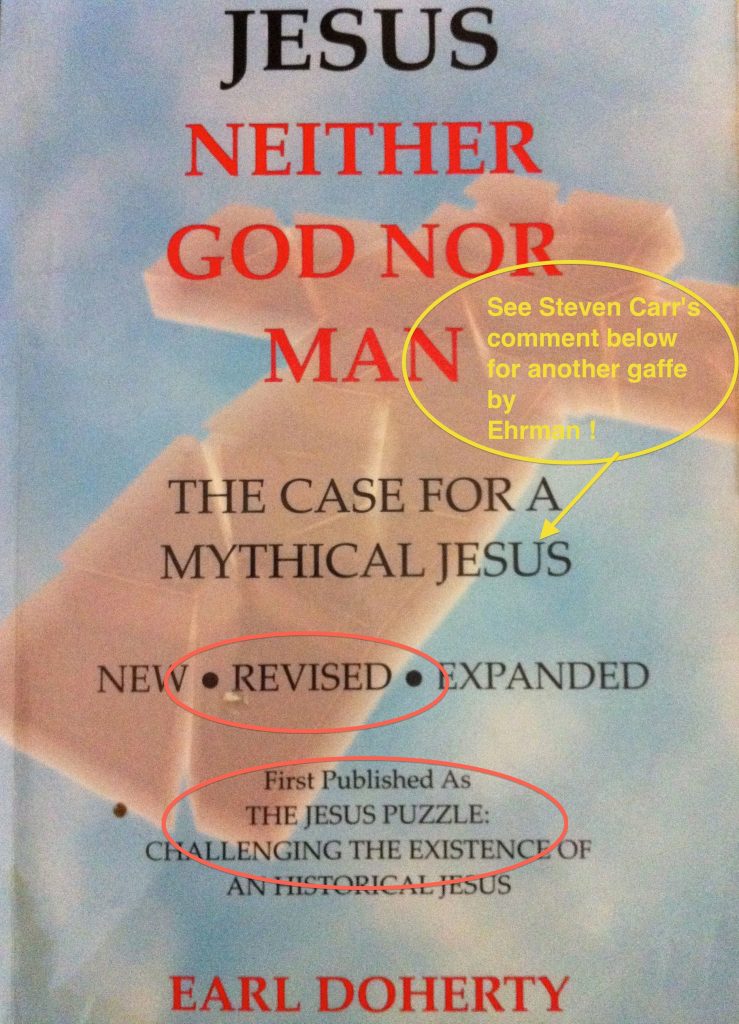

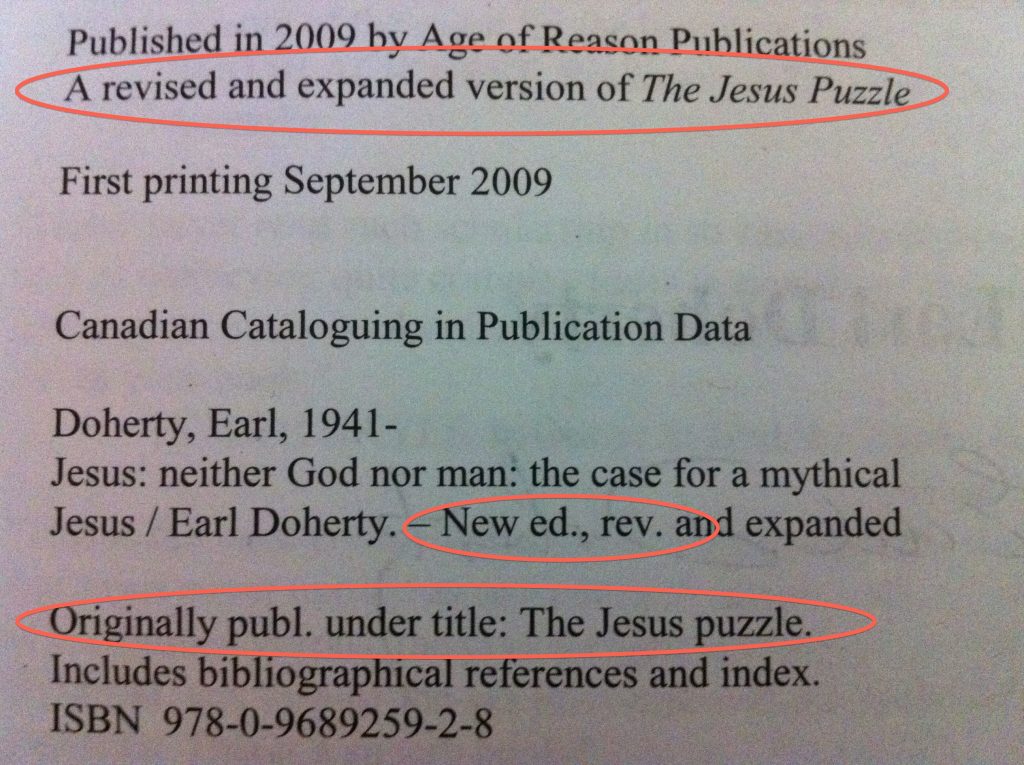

The problem with mythicists such as Doherty, Salm, Zindler, Wells, Ellegard, Price is that they engage with the mainstream scholarly literature devoted to studies of Christian origins and the historical Jesus. This poses a problem for anti-mythicist scholars such as Ehrman and McGrath. It forces them to do two things:

- Accuse the mythicists of dishonesty because they dare cite works that are not written by mythicists when they find in those works some point that they believe supports their case;

- Argue against mythicism by means of just one particular argument as if the many opposing viewpoints of their own peers simply do not exist. That is, they must suppress the fact that there are mainstream scholars who do support some particular details found in mythicist arguments.

The fallacious charge of dishonesty

I addressed #1 only recently at Devious Doherty or Erring Ehrman so won’t repeat myself here. I will add a brief note from Richard Carrier’s list of axioms of historical method:

Axiom 12: When one of us cites a scholar, it should only be assumed we agree with what they say is essential to the point we cite them for. (p. 34 of Proving History)

What happens is that when, say, Earl Doherty cites scholarly works supporting his view that 1 Corinthians 2:8 was originally understood by Paul to mean demons were responsible for the crucifixion of Christ, hostile critics retort that those same scholars also argue that they crucified Jesus by proxy, that is, through the Romans. They certainly do, and it is well understood that they do since it is well understood that Doherty is arguing a position against the views of the general scholarly community. It is clear and obvious to everyone that those scholars are not also mythicists. In their attempts to disallow Doherty the right to use scholarly views to support any point at all he is making in his argument for mythicism they accuse him of being dishonest by quoting scholars who do not agree with his larger point. (See Devious Doherty or Erring Ehrman for details.)

There’s a converse to this. Carrier expands on this axiom from that converse position. One might call it the fallacious charge of gullibility, but Carrier calls it the baggage fallacy:

This kind of ‘baggage’ fallacy (often deployed as a variety of the text-book fallacy of “poisoning the well”) is common enough to warrant particular condemnation. In fact, I see this fallacy committed so regularly, so widely, by accomplished scholars who ought to know better, that I feel the need to call particular attention to it now, in the hopes it will forestall a repeat performance. If you cite a scholar as proving point A, and that same scholar also argues B, but B is not necessary to A, then it is a fallacy for anyone to assume you agree with B, and a fallacy to employ this assumption to argue that if B is not credible then A is not credible. I call this the ‘baggage’ fallacy because it amounts to saddling an author with all the ‘baggage’ attached to the scholar he cites or the views he defends, when such attachment is neither entailed nor warranted. Just because I take certain positions or arrive at certain conclusions is no excuse to impute to me all the baggage that is usually supposed to come along with those positions or conclusions.

For example, when I argue a point (such as that distinct elements of Osiris cult can be seen in early Jesus cult), it might be assumed I agree with something else that supposedly goes along with this (such as that all elements of Osiris cult were present in early Jesus cult, or that Jesus is merely Osiris under another name, of that Christians just “borrowed” and “revamped” an Egyptian religion). That would be mistaken. . . . The same fallacy also results when I agree with something a particular book said, or cite it as a reference of importance on a specific subject, and then it’s assumed I agree with everything that book said or its author elsewhere defends. (p. 35)