In his review of Maurice Goguel‘s attack on Jesus mythicism Earl Doherty writes (with my emphasis):

In his review of Maurice Goguel‘s attack on Jesus mythicism Earl Doherty writes (with my emphasis):

It was at the opening of the 20th century that the first serious presentations of the Jesus Myth theory appeared. The earliest efforts by such as Robertson, Drews, Jensen and Smith were, from a modern point of view, less than perfect, lacking a comprehensive explanation for all aspects of the issue. Pre-Christian cults, astral religions, obscure parallels with foreign cultures, even the epic of Gilgamesh, went into a somewhat hodge-podge mix; many of them didn’t seem to know quite what to do with Paul. It wasn’t until the 1920s that Paul-Louis Couchoud in France offered a more coherent scenario, identifying Christ in the eyes of Paul as a spiritual being. (While not relying upon him, I would trace my type of thinking back to Couchoud, rather than the more recent G. A. Wells who, in my opinion, misread Paul’s understanding of Christ.)

More recently on this blog Earl Doherty stated in relation to this 1920’s French mythicist (again my emphasis):

Prior to Wells, the mythicist whose views were closest to my own was Paul-Louis Couchoud who wrote in the 1920s, though I took my own fresh run at the question and drew very little from Couchoud himself.

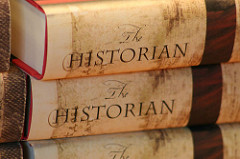

I have recently acquired a two volume English translation of Couchoud’s work titled The Creation of Christ: An Outline of the Beginnings of Christianity, translated by C. Bradlaugh Bonner and published 1939.

Today I did a very rough and dirty bodgie job of scanning the introductory chapters of this book and making them word-searchable. But if you are not a fuss-pot for perfection and are curious about how Couchoud opens his argument I share here the opening pages of this two volume work. Continue reading “Earl Doherty’s forerunner? Paul-Louis Couchoud and the birth of Christ”