.

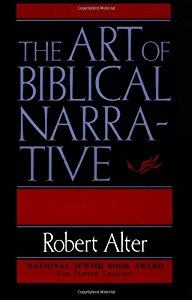

| A recent book by Jacob Licht, Storytelling in the Bible (Jerusalem, 1978), proposes that the “historical aspect” and the “storytelling” aspect of biblical narrative be thought of as entirely discrete functions that can be neatly peeled apart for inspection — apparently, like the different colored strands of electrical wiring.

This facile separation of the inseparable suggests how little some Bible scholars have thought about the role of literary art in biblical literature. (Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative, p. 32) |

.

By “historical fiction” I mean a fictitious tale, whether it is a theological parable or not, set in a real historical time and place. Authors of “historical fiction” must necessarily include real historical places and real historical persons and events in their narrative or it will be nothing more than “fiction”. Ancient authors are known to have written “historical fiction” as broadly defined as this. We have the Alexander Romance by Heliodorus that is a largely fictitious dramatization of the person and exploits of Alexander the Great. Of more interest for our purposes here is Chariton’s tale of Chaereas and Callirhoe. These are entirely fictitious persons whose adventures take place in a world of historical characters who make their own appearances in the novel: the Persian emperor, Artaxerxes II; his wife and Persian queen, Statira; the Syracusan statesman and general of the 410s, Hermocrates. There are allusions to other possible historical persons. Sure there are several anachronisms that found their way into Chariton’s novel. (And there are several historical anachronisms in the Gospels, too.) Chariton even imitated some of the style of the classical historians Herodotus and Thucydides.

In this way Chariton imitates the classical historians in technique, not for the purpose of masquerading as a professional historian, but rather, as Hagg (1987, 197) suggests, to create the “effect of openly mixing fictitious characters and events with historical ones.” (Edmund Cueva, The Myths of Fiction, p. 16)

A word to some critics: This post does not argue that Jesus did not exist or that there is no historical basis to any of the events they portray. It spoils a post to have to say that, since it ought to be obvious that demonstrating a fictitious nature of a narrative does not at the same time demonstrate that there were no analogous historical events from which that narrative was ultimately derived. What the post does do, however, is suggest that those who do believe in a certain historicity of events found in the gospels should remove the gospels themselves as evidence for their hypothesis. But that is all by the by and a discussion for another time. Surely there is value in seeking to understand the nature of one of our culture’s foundational texts for its own sake, and to help understand the nature of the origins of culture’s faiths.

This post is inspired by Robert Alter’s The Art of Biblical Narrative. Alter believes that the reason literary studies of the Bible were relatively neglected for so long is because of the cultural status of the Bible as a “holy book”, the source of divine revelation, of our faith. It seems gratuitously intrusive or simply quite irrelevant to examine the literary structure of a sacred book. So the main interest of those who study it has been theology. I would add that, given the Judaic and Christian religions of the Bible claim to be grounded in historical events, the relation of the Bible’s narratives to history has also been of major interest.

But surely the first rule of any historical study is to understand the nature of the source documents at hand. That means, surely, that the first thing we need to do with a literary source is to analyse it see what sort of literary composition it is. And as with any human creation, we know that the way something appears on the surface has the potential to conceal what lies beneath.

Only after we have established the nature of our literary source are we in a position to know what sorts of questions we can reasonably apply to it. Historians interested in historical events cannot turn to Heliodorus to learn more biographical data about Alexander the Great, nor can they turn to Chariton to fill in gaps in their knowledge about Artaxerxes II and Statira, because literary analysis confirms that these are works of (historical) fiction.

Some will ask, “Is it not possible that even a work of clever literary artifice was inspired by oral or other reports of genuine historical events, and that the author has happily found a way to narrate genuine history with literary artistry?”

The answer to that is, logically, Yes. It is possible. But then we need to recall our childhood days when we would so deeply wish a bed-time fairy story, or simply a good children’s novel, to have been true. When we were children we thought as children but now we put away childish things. If we do have at hand, as a result of our literary analysis, an obvious and immediate explanation for every action, for every speech, and for the artistry of the way these are woven into the narrative, do we still want more? Do we want to believe in something beyond the immediate reality of the literary artistry we see before our eyes? Is Occam’s razor not enough?

If we want history, we need to look for the evidence of history in a narrative that is clearly, again as a result of our analysis, capable of yielding historical information. Literary analysis helps us to discern the difference between historical fiction and history that sometimes contains fictional elements. Or maybe we would expect divine history to be told with the literary artifice that otherwise serves the goals and nature of fiction, even ancient fiction.

The beginning of the (hi)story

Take the beginning of The Gospel According to St. Mark. Despite the title there is nothing in the text itself to tell us who the author was. This is most unlike most ancient works of history. Usually the historian is keen to introduce himself from the start in order to establish his credibility with his readers. He wants readers to know who he is and why they should believe his ensuing narrative. The ancient historian normally explains from the outset how he comes to know his stuff. What are his sources, even if in a generalized way. The whole point is to give readers a reason to read his work and take it as an authoritative contribution to the topic.

The Gospel of Mark does indeed begin by giving readers a reason to believe in the historicity of what follows, but it has more in common with an ancient poet’s prayer to the Muses calling for inspiration and divinely revealed knowledge of the past than it does with the ancient historian’s reasons.

As it is written in the prophets, Behold, I send my messenger . . . .

That’s the reason the reader knows what follows is true. It was foretold in the prophets. What need we of further witnesses?

Yes, some ancient historians did from time to time refer to a belief among some peoples in an oracle. But I can’t off hand recall any who claimed the oracle was the source or authority of their narrative. I have read, however, several ancient novels where divine prophecies are an integral part of the narrative and do indeed drive the plot. Events happen because a divine prophecy foretold them. That’s what we are reading in Mark’s Gospel here from the outset, not unlike the ancient novel by Xenophon of Ephesus, The Ephesian Tale, in which the plot begins with and is driven by an oracle of Apollo.

Note, too, how the two lead characters in the opening verses are introduced. Continue reading “Why the Gospels Are Historical Fiction”