See

Where did Islamic State come from, and what does it really want? By Eleri Mai Harris

It even includes an explanation of the apocalyptic beliefs of certain of the ISIS leadership, linking nicely to my previous post:

Musings on biblical studies, politics, religion, ethics, human nature, tidbits from science

See

Where did Islamic State come from, and what does it really want? By Eleri Mai Harris

It even includes an explanation of the apocalyptic beliefs of certain of the ISIS leadership, linking nicely to my previous post:

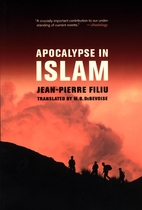

Recently I was curious enough to learn what today’s Muslim teachings about the “end times” were to pick up and read two books:

Recently I was curious enough to learn what today’s Muslim teachings about the “end times” were to pick up and read two books:

Filiu’s work is by far to be preferred for anyone wanting a more complete overview. The 2005 publication has its strengths — I was fascinated by the historical accounts of the various Mahdist movements, in particular the nineteenth century Mahdi of the Sudan of Gordon of Khartoum fame — but it does lose some credibility with its clearly failed analysis of modern extremist Islamist movements, in particular with respect to the questions it was raising in relation to Osama bin Laden. Furnish is determined to focus on Sunni Muslim movements in order to “balance” the much vaster literature on Mahdism among the Shia Muslims. (The Shia dominate Iran but are also significant forces in Lebanon-Syria and parts of Iraq.) That’s a key reason Filiu’s book is to be preferred by anyone interested in Muslim end times teachings more generally.

Filiu’s work is by far to be preferred for anyone wanting a more complete overview. The 2005 publication has its strengths — I was fascinated by the historical accounts of the various Mahdist movements, in particular the nineteenth century Mahdi of the Sudan of Gordon of Khartoum fame — but it does lose some credibility with its clearly failed analysis of modern extremist Islamist movements, in particular with respect to the questions it was raising in relation to Osama bin Laden. Furnish is determined to focus on Sunni Muslim movements in order to “balance” the much vaster literature on Mahdism among the Shia Muslims. (The Shia dominate Iran but are also significant forces in Lebanon-Syria and parts of Iraq.) That’s a key reason Filiu’s book is to be preferred by anyone interested in Muslim end times teachings more generally.

A reassuring message that comes through is just how unimportant are teachings about last days and end time apocalypse in the political and everyday thinking of Muslims generally. As among Christians (and my impression is that even more-so than among North American Christians) the overwhelming majority of Islamic teachers and general body of believers tend to look down upon minorities in their midst who get too carried away with apocalyptic speculations. Both books were published before Islamic State burst on the scene in 2014 but little that I have read about IS changes this overall balance of interest.

Of interest to me were the sources of the various apocalyptic beliefs. Comparable Christian beliefs are taken from canonical sources like the books of Revelation and Daniel. These are generally interpreted through the dispensationalist concepts originating with the Scofield Reference Bible. Add a touch of Hal Lindsay and maybe a little Nostradamus for the most extreme and that’s basically it. Islamic apocalypticism is more eclectic by spades. Much of it even draws upon the Christian sources just mentioned! There are Islamic texts, certain hadiths, that do form the basis of Muslim apocalyptic but they are relatively light on with respect to details and narrative flow.

As for dates, 1979 was a turning point for the Islamic world.

For the significance of 1979 compare Jason Burke’s analysis of the rise of global Islamic militancy. Two Vridar posts discussing Burke’s explanation:

The triple shocks of 1979 were a turning point although various clear ideas of what to make of these events did not coalesce overnight. This period was the beginning of the fifteenth Muslim century and nothing eschatalogical had been foretold of this period so it took a little while to reinterpret and understand anew various prophecies. Afghanistan and Iran may look remote to Christians but they are the centre of Khurasan, a “mythical land” long associated with Afghanistan and where the Messiah’s appearance was foretold.

I could not fail to be interested in various prophetic views of Jesus. They vary from Jesus returning to condemn everyone who failed to convert to Islam to Jesus inspiring a special tolerance and place for Christians. Another reminder that the Muslim religion is anything but a monolith.

First comes the Antichrist to the land of Sham, or Syria. Other prophecies locate him in Khurasan. Continue reading “Jesus in the Muslim Apocalypse”

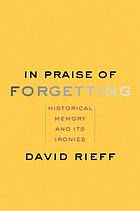

What’s the point of remembering historical traumas? Has remembering the Holocaust prevented genocides? What of 9/11? Why do we remember these things? To what purposes do we put our memories? Are they always for good?

But most times they are not memories at all, not really. They are political stories we have chosen to latch on to for specific reasons. No-one in Ireland “remembers” the Irish Easter Rising. No-one in Australia “remembers” Gallipoli. Why do we sacralize certain political stories we call memories? And why do we even call them memories? To what use do we put these “memories”?

Remembrance as a species of morality has become one of the more unassailable pieties of the age. Today, most societies all but venerate the imperative to remember. We have been taught to believe that the remembering of the past and its corollary, the memorialising of collective historical memory, has become one of humanity’s highest moral obligations.

But what if this is wrong, if not always, then at least part of the time? What if collective historical memory, as it is actually employed by communities and nations, has led far too often to war rather than peace, to rancour and resentment rather than reconciliation, and the determination to exact revenge for injuries both real and imagined, rather than to commit to the hard work of forgiveness?

That’s quoted from an article by war correspondent David Rieff in a Guardian article, The cult of memory: when history does more harm than good.

Provocative, yes. Thought-provoking, too.

The questions I opened with are based on an interview with David Rieff on the Late Night Live program on Australia’s Radio National. Interviewer Philip Adams: In praise of forgetting. That’s the link to the most excellent interview. Promise to listen to it before you go any further. (I have not yet fully read the Guardian article I quoted from above but this post is inspired by the interview.)

The two related books by David Rieff:

His recently published In praise of forgetting : historical memory and its ironies. And not forgetting his earlier Against Remembrance.

Do not comment on this post unless you are prepared to stay to engage with possible alternative views and defend your own ideas in civil discourse. Angry and fly-by-nighter comments may be deleted.

Do not comment on this post unless you are prepared to stay to engage with possible alternative views and defend your own ideas in civil discourse. Angry and fly-by-nighter comments may be deleted.

Studying Islam DE-radicalized him!? His deepening knowledge and understanding of Islam from the scholars turned him away from support for ISIS.

I don’t know if readers outside Australia will be able to access the video on this page but at least there is a partial transcript: Australian radical explains why he once supported IS – and why he stopped.

The TV doco is a look at a de-radicalization program in Australia (with comparisons with the Netherlands, iirc). The experts interviewed say the same things as the experts who have written the books I have posted about several times now:

There are questions left hanging, however. Though certain individuals are deradicalized through a deepening study of Islam they appear to maintain a strong Islamist belief system. Only an Islamism that is opposed to violence. That’s good, at least the part about being opposed to violence is good.

But if they still fail to truly appreciate and subscribe to Enlightenment values, democracy as it is understood in the Western tradition, pluralism and the value of secularism to lubricate a happily functioning society — then are we feeding another social problem that will need to be confronted in the future?

How do we determine the best way to interpret patterns and parallels between the Gospels and other literature?

Here is one parallel that someone asks us to consider:

Fishing for men.

While at the Sea of Galilee, Jesus predicted that his followers would fish for men.

“From now on you will catch men.” Luke 5:10Titus’ followers then fish for men on the Sea of Galilee.

“And for such as were drowning in the sea, if they lifted their heads up above the water, they were either killed by darts, or caught by the vessels.” Wars of the Jews, 3, 10, 527

I am not convinced for the following reasons:

There is no overlapping of theme or idea. The context of the passage in Luke tells us that the idea of “fishing for men” is to “catch” disciples, converts. The metaphor originates in Jeremiah where it means judgment:

“But now I will send for many fishermen,” declares the LORD, “and they will catch them. After that I will send for many hunters, and they will hunt them down on every mountain and hill and from the crevices of the rocks. My eyes are on all their ways; they are not hidden from me, nor is their sin concealed from my eyes. — Jeremiah 16;16-17

So the evangelist (author of the Gospel) has inverted the metaphor from one of condemnation to one of salvation.

The Josephus passage makes no reference to “fishing” and any normal reading of the slaughter would scarcely bring to mind images of “fishing”.

The reason I am persuaded that the Lukan saying is taken from Jeremiah and not from Josephus is that it matches a core criterion often listed as a vital indicator of a genuine literary relationship:

Dennis MacDonald calls it “interpretability”. I have summarized the idea as:

interpretability or intelligibility — the capacity of the original text to make sense of some detail in the new work (e.g. Is there some detail or theme in a story that has mystified modern readers over why it was included, with a satisfactory explanation appearing if the author knew another text where the same detail made more sense? Sometimes borrowing from another text may produce awkwardness or some incoherence in order to fit it in the new work.)

Andrew Clark calls it “parallel theme” and says it adds meat to other indications of borrowing:

parallel theme – this cannot stand on its own but adds strength where it exists to other criteria

Thomas Brodie also uses the term “interpretability” — “or the intelligibility of the differences”

Differences will sometimes be very great, but what counts is whether the differences can be explained in a way that deepens our understanding of the new text. Sometimes such explanations can reveal new surprises about the nature of the reworked document.

One may object that the proposed parallel between Luke and Josephus in the above example may not work on its own but does carry weight when set in the context of a number of other parallels. My objection to this argument is that there is no reason to see the massacre in the sea as a parallel at all no matter what setting it appears in.

Is it possible that the evangelist has used both Jeremiah and Josephus? Anything is possible, but since the argument for the use of Jeremiah as the source is entirely sufficient there is no need to involve the Josephan passage.

But what about the following parallels between Theudas (in Josephus) and John the Baptist, this time from Lena Einhorn: Continue reading “On Parallels”

Rene Salm translates from the German:

http://www.mythicistpapers.com/2016/05/27/a-shift-in-time-l-einhorn-book-review-pt-2/

What life in a cult was like: “We gave away our critical thinking and moral code and surrendered it to him” — Gary Kramer writes about his interviews with former disciples of Buddhafield, including disciple filmmaker of Holy Hell.

Buddhafield espoused starkly different teachings and practices from the Christian cult I belonged to — and both Buddhafield and Christian cults are very different from Islamist political/terrorist “cults” I have spoken about before. The similarities, however, are also very real. I quote from Kramer’s interview those points that also point to my experience and what I have read in the research about terrorist cells.

What led to involvement? Will Allen (WA):

I was on a quest for happiness. I was pretty burned out from college. I liked the teachings I heard, and the people I met, and that was the beginning of the end. I was young and looking for some kind of secret to life—how to live my life and give it purpose.

Another member (David Christopher – DC) replied:

We were looking for something deeper. Our families are a cult. I have a new definition for cult: a group or organization that inhibits your thinking through guilt, shame, or coercion. That can be your family, it can be your church. . . . Most everyone in our community wanted something more—they saw something under the veil and wanted more than just the superficial, and that’s how they entered into this.

You can’t just join the Buddhafield. It’s hard to get in. It’s selective, and secretive. I realized quickly that there was something going on. I wasn’t invited in. There was a process you needed to go through… Eventually you get invited. . . . It was “this is more your family,” and I felt that way—it was way more intimate than my own family.

Why stay?

It’s like any relationship. You find the good and hold on to that as long as you can and overlook all the negatives. . . . (WA)

The craziness wasn’t really apparent for most of us. I’d like to say 80 percent of it is so fricking amazing that you can live in this state of bliss. And 20 percent was a little weird but you say, “I’m not going to look at that part.” (DC)

Comment on the culture, the rules: Continue reading “Holy Hell: What life in a cult was like”

Golden Dawn party attempts to shut down Mythicism Conference

A translation of part of the letter by Golden Dawn to the Mayor of Athens:

The Greek Constitution stated that the Orthodox Christian Faith is the dominant religion of our homeland. How can the ministry protect protect the holies of 2000 years of our homeland, if it does not intervene and allows the conference to take place, which is potentially heretical and aims to destroy the faith of Greeks?

A landmark in national life has just been passed. For the first time in recorded history, those declaring themselves to have no religion have exceeded the number of Christians in Britain. Some 44 per cent of us regard ourselves as Christian, 8 per cent follow another religion and 48 per cent follow none. . . . We can more accurately be described now as a secular nation with fading Christian institutions. . . . .

Christians, for their part, should not automatically associate a decline in religiosity with a rise in immorality. On the contrary, Britons are midway through an extraordinary period of social repair: a decline in teenage pregnancies, divorce and drug abuse, and a rise in civic-mindedness.

That’s from a leading article in the 28th May 2016 edition of The Spectator: Britain really is ceasing to be a Christian country.

Once more exploring a question raised by Lena Einhorn in A Shift in Time — this time with doubts….

Was Jesus originally the Egyptian prophet we read about in the works of the ancient Jewish historian Josephus? Lena Einhorn seems to think so in A Shift in Time where she lists seven points in common between them. I won’t discuss those seven points but will look at her seventh:

And last, but not least, “the Egyptian” is defeated on the Mount of Olives, which is where Jesus was arrested. It is also from there that both men have declared their prophecies [that the walls of Jerusalem would fall down].

Actually Jesus predicted the walls of the buildings, in particular the Temple, would be pulled down, not the walls of Jerusalem. I have thought of the Egyptian as attempting to re-enact Joshua’s feat of miraculously having the walls of a great city collapse while Jesus (the Greek form of Joshua) spoke of the destruction of the Temple. But that’s a caveat we’ll set aside for now but return to later.

To begin, let’s be sure we have the picture. Josephus writes about the Egyptian twice, first in Wars (written about 78 CE) and second in Antiquities (about 94 CE). Here’s what he tells us:

But there was an Egyptian false prophet that did the Jews more mischief than the former; for he was a sorcerer, and pretended to be a prophet also, and got together thirty thousand men that were deluded by him;

these he led round about from the wilderness to the mount which was called the Mount of Olives, and was ready to break into Jerusalem by force from that place; and if he could but once conquer the Roman garrison and the people, he intended to domineer over them by the assistance of those guards of his that were to break into the city with him.

But Felix prevented his attempt, and met him with his Roman soldiers, while all the people assisted him in his attack upon them, insomuch that when it came to a battle, the Egyptian ran away, with a few others, while the greatest part of those that were with him were either destroyed or taken alive; but the rest of the multitude were dispersed every one to their own homes, and there concealed themselves.

War of the Jews 2.261–263

Then about fifteen years later Josephus wrote:

There came out of Egypt about this time to Jerusalem one that said he was a prophet, and advised the multitude of the common people to go along with him to the Mount of Olives, as it was called, which lay over against the city, and at the distance of five furlongs.

He said further, that he would show them from hence how, at his command, the walls of Jerusalem would fall down; and he promised them that he would procure them an entrance into the city through those walls, when they were fallen down.

Now when Felix was informed of these things, he ordered his soldiers to take their weapons, and came against them with a great number of horsemen and footmen from Jerusalem, and attacked the Egyptian and the people that were with him. He also slew four hundred of them, and took two hundred alive.

But the Egyptian himself escaped out of the fight, but did not appear any more.

Antiquities of the Jews 20.169–172

The story has changed in some details over those fifteen years. The event itself is set in the 50s CE. Josephus first writes about it around 20 or more years later. That’s about the same time span between today and the catastrophic raid on the Branch Davidian cult in Waco, Texas. Josephus appears to be saying that the Egyptian’s plan was to attack Jerusalem without any thought of a miracle to open the gates for them.

Approximately thirty five years after the event (compare today’s distance from the assassination attempt on President Reagan) Josephus introduces the Egyptian’s prophecy to command the walls of Jerusalem to do a Jericho.

So unless I am missing something hidden by a poor translation it seems that there is room for doubt that the Egyptian really was known at the time to have told his followers that the walls would obey his voice. One can imagine people talking about this fellow and mockingly asking how he could possibly have seriously thought he would take over Roman occupied Jerusalem, and how from such scoffing someone suggests he probably thought he could repeat the Jericho miracle. Or maybe he really did make such a declaration and Josephus simply failed to mention it in his first account. However that may be, years later when the event was recalled this detail did become part of the story. Who knows if it was Josephus’s memory or if he picked up the detail from someone else?

What, then, connects the Mount of Olives setting in the story of the Egyptian with our accounts of Jesus?

There are two links. Continue reading “Jesus and “The Egyptian”: What to make of the Mount of Olives parallel?”

ISIS just delivered its ‘weakest message’ ever by Pamela Engel (Business Insider Australia, h/t IntelWire)

Indeed, we do not wage jihad to defend a land, nor to liberate it, or to control it. . . .

We do not fight for authority or transient, shabby positions, nor for the rubble of a lowly, vanishing world. … If we were able to avert a single fighter from fighting us, we would do so, saving ourselves the trouble. However, our Quran requires us to fight the entire world, without exception. . . .

Do you, oh America, consider defeat to be the loss of a city or the loss of land? Were we defeated when we lost the cities in Iraq and were in the desert without any city or land? And would we be defeated and you be victorious if you were to take Mosul or Sirte or Raqqah or even take all the cities and we were to return to our initial condition? Certainly not!

ISIS is on the ropes. They once propagated a message and aura of invincibility and recruits came to them from around the world. That’s all in reverse now.

Unfortunately other news has pointed to Al Qaeda and its “partner” Al-Nusra re-emerging in Syria (Al Qaeda About to Establish Emirate in Northern Syria and Al Qaeda Blessing for Syrian Branch to Form Own Islamic State). I have almost completed Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards by Afshon Ostovar. Ostovar has answered a question I had about the exact nature of Iran’s involvement in Syria. Just as an Islamist militia has been built throughout Iran to violently cower dissidents and to be prepared to wage asymmetric warfare against a future invasion, so Iranian trainers have been training Syrians by the thousands to replicate the same type of organized gangs in Syria. Syria is the most depressing news.

Christianity may teach us to be honest but as long as dishonesty serves the interests of faith I’m sure God forgives.

A certain Butler University Professor (his blog makes it clear he writes in his capacity as a Butler academic) who is well known for his strident dogmatism on the question of the historicity of Jesus has been at it again.

He writes in response to a “meme” that he realizes is false or flat wrong in every way except one: it scorns mythicism!

First falsehood:

the attempt to argue that because someone is only mentioned in the New Testament, therefore they are not historical, simply does not work.

Of course he cites no instance of anyone arguing this way. No publication putting in a word for the mythicist case that I know of has ever suggested that “because someone is only mentioned in the New Testament, therefore they are not historical”.

But he does say something that is obviously true. I think we can all agree with the following:

Mythicist dogmatists and Christian fundamentalists are not at polar opposite ends of the spectrum, except on the trite matter of what they insist they know. Their approach is an all-or-nothing one that are mirror images of one another, two sides of the same coin.

There certainly are “mythicist dogmatists” who are as, well, dogmatic, as any Christian fundamentalist.

Then he writes something most professional:

Historians, on the other hand, are supposed to deal in a nuanced manner with evidence, and to recognize that each piece of evidence must be assessed separately and on its own terms.

But then he slips off the rails. Two true statements bracketed by two false ones. A nice chiastic structure.

And so the heart of the matter is this: mythicism – the complete dismissal of the historicity not just of accounts but of the individual portrayed in them – is as illogical and indefensible as claims of Biblical inerrancy – the complete acceptance of the historicity of everything in the Bible because the existence of individuals mentioned in it has been confirmed.

Notice where he slipped? At first he made the obvious statement that a “mythicist dogmatist” is as bad as a “Christian fundamentalist”, but here he speaks of “mythicism” generically. Mythicism itself is as bad as Christian fundamentalism. I would have thought “mythicism” would stand in this context as a counter to “Christianity”: just as Christianity has its fundamentalists so does mythicism have its dogmatists. Both stand outside the realm of serious discussion.

And then he underscores the point:

Neither mythicism nor Christian fundamentalism is engaged in the practice of history.

Not, “neither mythist dogmatism nor Christian fundamentalism”, nor, of course, “Neither mythicism nor Christianity….”

Then we meet the professional indignation:

And when historians and scholars object to this misuse of their work, mythicists and inerrantists typically respond in the same way: by insisting that the academy is in fact conspiring to cover up the truth or infested with an ideology that blinds us to the truth.

Interesting that he speaks of “historians and scholars”. Is he trying to impress readers once again that theologians like himself really are true historians and scholars? Certainly a good number of theologians do call themselves historians and in one sense they are, but even in their own ranks we find criticisms that their approach to history is quite different from the way other historians work. (Raphael Lataster demonstrated that most emphatically in his book. Recall a paper of his discussing historical Jesus methodology that was rejected by a scholarly Biblical publisher was accepted by a Historical conference.) And of course our Butler Professor cannot be ignorant of the fact that it is theologians themselves, his own peers, who regularly complain about the ideology that blinds them as a whole to seriously radical ideas.

Recall again his point:

Historians, on the other hand, are supposed to deal in a nuanced manner with evidence, and to recognize that each piece of evidence must be assessed separately and on its own terms.

Do I need to quote again here the many instances of nuance and tentativeness and scholarly humility in the way scholarly mythicists (scholarly referring to any mythicist who argues in a scholarly manner — leaving aside the dogmatists) very often present their arguments and set them beside a list the many abusive and dogmatic denunciations of theologian “historians and scholars” like the Butler Professor himself when arguing for the historicity of Jesus?

Another illustration of the only way a devoted member of a “tribe” — whether religious cult or ISIS — can begin to loosen their attachment and head towards the Exit door appeared in AP’s The Big Story: Islamic State’s lasting grip is a new hurdle for Europe, US written by Lori Hinnant. Its message is consistent with my own experience or exiting a religious cult and with the scholarly research I have since read on both religious cults and terrorist groups, both Islamist and secular.

Lori Hinnant is discussing the experiences of a French program to “de-radicalise” former ISIS members. Its key sentence:

Only once doubts are seeded can young wouldbe jihadis themselves reason their way back to their former selves.

Attempting to argue them out with reason is futile. In the case of fundamentalist cults we can easily enough see why: their thinking is entirely circular. There is no escaping. All “contrary thoughts” are from Satan and to be cast down, writes Paul in 2 Corinthians 10:5. It is no different with Islamic extremists, as previous posts have illustrated. Membership of the group is the foundation of the identity of each member; the group is their family and the bond stimulates the dopamine. Life only has meaning as an active member of the group.

Try talking anyone out of leaving their family and walking away from the cause that gives their life meaning.

There is no reasoning with someone in the thrall of a jihadi group, those who run the program say, so the recruits have to experience tangible doubts about the jihadi promises they once believed. Bouzar said that can mean countering a message of antimaterialism by showing them the videos of fighters lounging in fancy villas or sporting watches with an Islamic State logo. Or finding someone who has returned from Syria to explain that instead of offering humanitarian aid, the extremists are taking over entire villages, sometimes lacing them with explosives. Only once doubts are seeded can young wouldbe jihadis themselves reason their way back to their former selves, she said.

That’s how it’s done. It won’t happen immediately. At first the response to “proofs” of hypocrisy among the group’s leaders and deception in what they promise will be met with incredulity, a suspicion that the stories are all lies. But show enough with the clear evidence that the stories are not fabrications and slivers of doubts have a chance of seeping in. Some will react with even more committed idealism, convincing themselves that they will fight the corruption within. But their powerlessness will eventually become apparent even to themselves.

Only then will the member begin to “reason their [own] way back to their former selves”.