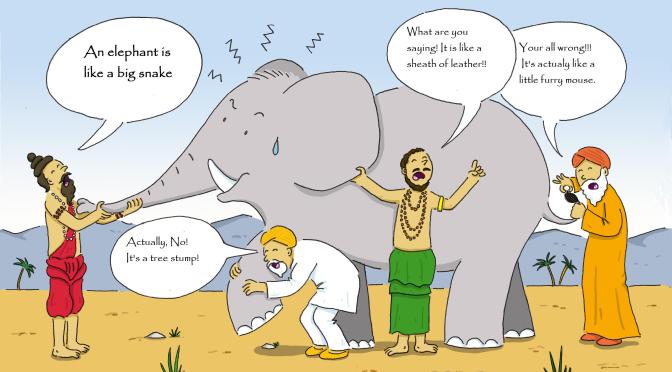

Religion is more than the faiths most of us grew up with. Christianity, Judaism, Islam — these represent only one family branch of religion. If we want to understand “what religion is” and explore why it is that religion is so pervasive among humanity then it’s a good idea to have as complete a picture as possible of this thing called “religion” and not limit ourselves to just one part of it. Remember the parable of the blind men describing the elephant.

Here are some reminders of why we should not limit our view of religion to certain features of Christianity or the Muslim faith. They are taken from Pascal Boyer’s Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought, 2001.

Supernatural agents can be very different

Religion is about the existence and causal powers of nonobservable entities and agencies. These may be one unique God or many different gods or spirits or ancestors, or a combination of these different kinds. Some people have one “supreme” god, but this does not always mean that he or she is terribly important. In many places in Africa there are two supreme gods. One is a very abstract supreme deity and the other is more down-to-earth, as it were, since he created all things cultural: tools and domesticated animals, villages and society. But neither of them is really involved in people’s everyday affairs, where ancestors, spirits and witches are much more important.

Some gods even die. Boyer reminds us that many Buddhists think gods themselves go through the cycles of reincarnations. The only reason generations of humans worship the same gods is because the gods take a lot longer to get around to dying.

Many spirits are really stupid

We think of religion as devotion to an all-knowing and all-wise being and perhaps his angelic agents. But

In Siberia, for instance, people are careful to use metaphorical language when talking about important matters. This is because nasty spirits often eavesdrop on humans and try to foil their plans. Now spirits, despite their superhuman powers, just cannot understand metaphors. They are powerful but stupid.

In places in Africa people guard against praising the good looks or good nature of children by telling their parents how ugly or unpleasant they are. The idea is to keep their attributes secret from witches who would otherwise try to eat them. Sometimes children are even given names with disgraceful associations for the same reason.

In Haiti one of the worries of people who have just lost a relative is that the corpse might be stolen by a witch. To avoid this, people sometimes buried their dead with a length of thread and an eyeless needle. The idea was that witches would find the needle and try to thread it, which would keep them busy for centuries so that they would forget all about the corpse. People can think that supernatural agents have extraordinary powers and yet are rather easily fooled.