H/T a tweet liking a tweet from another tweet. . . .

2019-08-22

Love it! — BREXIT

Musings on biblical studies, politics, religion, ethics, human nature, tidbits from science

At present this includes posts on history of Zionism and modern Israel and Palestine as well as current events. Continue this setup? What of other histories? Adjust name of category? Currently includes Islamism (distinct from Islam) as an ideology of terrorism. Also currently includes Islamophobia and hostile denunciations of Islam — but see the question on Islam in Religion and Atheism.

H/T a tweet liking a tweet from another tweet. . . .

A few weeks ago, I was dealing with a mold issue in our RV’s bathroom. (Note: If you see mushrooms growing out of a crack in the wall, it’s usually a bad sign.) Having resigned myself to working with gloves, wearing a mask, sitting uncomfortably on the floor for at least an hour, I resolved to find a long audio program on YouTube and let it play while I worked. I happened upon a presentation by Dr. Lewis Sorley, based mainly on his book, Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam. (You can find the video at the end of this post.)

A few weeks ago, I was dealing with a mold issue in our RV’s bathroom. (Note: If you see mushrooms growing out of a crack in the wall, it’s usually a bad sign.) Having resigned myself to working with gloves, wearing a mask, sitting uncomfortably on the floor for at least an hour, I resolved to find a long audio program on YouTube and let it play while I worked. I happened upon a presentation by Dr. Lewis Sorley, based mainly on his book, Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam. (You can find the video at the end of this post.)

I had studied the Vietnam War as an undergraduate history major back in the 1980s, so much of what Sorley had to say covered old ground for me. Back in those days, of course, we could still refer to it as America’s Longest War without worrying whether some other disastrous Asian war might overtake it. After all, we had “learned the lessons of Vietnam,” right?

Later, as a student at Squadron Officer School, I certainly thought we had learned those lessons. From a policy perspective, the first lesson had to be clarity of purpose. On the military side, we would never again fight a limited war of attrition; instead, we would use overwhelming force to achieve clear objectives. In a nutshell, this is the “Get-In-and-Get-Out” Doctrine: Know your objectives. Achieve them in minimum time with minimal loss of life.

We would absolutely avoid any future quagmires. Or so we thought.

I should mention that several other lessons — both spoken and unspoken — arose out of the Vietnam experience. The practice of embedding journalists within fighting units came out of the beliefs that the press should not have been permitted to work as independent observers and that allowing them to move freely in South Vietnam had been a mistake.

An expanding set of myths about why we lost the war blossomed quickly into an alternate history in which unreliable draftees, fickle politicians in Washington, pinko journalists, and the hippy peace movement conspired to keep us from winning.

Some of these myths took hold naturally, as veterans told their personal stories, relating with frustration how the body counts didn’t seem to matter, that the V.C. would return again and again, that the stupid war of attrition didn’t work, and what’s more, nobody seemed to give a damn that it wasn’t working. That much was true.

Continue reading “Some Thoughts on the Lessons of Vietnam and the General Who “Lost” the War”

Arie Perliger, Director of Security Studies and Professor, University of Massachusetts Lowell, had the article From across the globe to El Paso, changes in the language of the far-right explain its current violence published in The Conversation a couple of days ago. In case you missed it, he writes . . . .

. . . a new trend among perpetrators of far-right violence: They want the world to know why they did it.

So they provide a comprehensive ideological manifesto that aims to explain the reasoning behind their actions as well as to encourage others to follow in their steps.

In the past, only leaders of far-right groups did this. Now, it’s common among lone-wolf perpetrators . . .

Then,

In the past decade, the language of white supremacists has transformed in important ways. It crossed national borders, broadened its focus and has been influenced by current mainstream political discourse.

Compare Patrick Cursius, the El Paso mass murderer, in his manifesto:

The best solution to this, for now, would be to divide America into a confederacy of territories with at least 1 territory for each race. This physical separation would nearly eliminate race mixing and improve social unity by granting each race self-determination within their respective territory(s).

Since the 19th century, the American white supremacy movement has stressed the superiority of Western culture and the need to preserve the dominance and racial purity of the white race. Racial segregation is essential. An example given by Perliger is 1980s KKK map of allocating set areas of the U.S. to particular races: Jews in New York, Hispanics in Florida, etc.

But recently, a growing number of far-right activists have preferred to focus on cultural and social differences between communities, rather than on attributes such as race and ethnic origin.

They justify their violence as a way to preserve certain cultural-religious practices, rather than relying on their old justification – maintaining the genetic purity of the white race. In these activists’ view, the battle has moved from genes to culture.

For example, a member of the National Socialist Movement, an American neo-Nazi organization, wrote in a 2018 online post that white American is an identity like African American or Jewish American. In a statement that probably wouldn’t have been made by previous generations of neo-Nazis, the member wrote that all whites should come together, using their knowledge and weapons, to stop non-Europeans from pushing their secular agenda via government and media power.

Continue reading “Understanding White Nationalism and Its Terrorism”

We saw the rise of “cultural racism” in France in the first post. Another term for the same type of racism found in the literature is the “new racism”. In a future post I’ll outline the rise of this new racism in Britain as a companion to the first post on its rise in France. For now, however, I present a description of the new racism as explored by Martin Barker in The New Racism: Conservatives and the Ideology of the Tribe (1981). Yes, it’s another old source. As mentioned earlier, I’m going through the sources I find often cited in more recent literature first.

The first point we notice in surveying the debates over and the expressions of the new racism is the centrality of the idea of a “way of life or a culture”

National consciousness is the sheet anchor for the unconditional loyalties and acceptance of duties and responsibilities, based on personal identification with the national community, which underlie civic duty and patriotism [Sherman, Alfred. ‘Why Britain can’t be wished away’, Daily Telegraph, 8 September 1978].

Thus Alfred Sherman, Director of the right-wing Institute for Policy Studies in one of the Daily Telegraph‘s regular centre-page pronouncements on race. We are bound together by feelings of oneness, and indeed these are strengthened by recognition that others are different. ‘It is from a recognition of racial differences that a desire develops in most groups to be among their own kind; and this leads to distrust and hostility when newcomers come in’ [Page]. Thus Robin Page, in another of these pronouncements. But Page was aware that this left him open to a charge of racism which he was keen to avoid. So he made it clear that ‘the whole question of race is not a matter of being superior or inferior, dirty or clean, but of being different‘ [ibid.].

(Barker, 20. My bolding in all quotations. I have exchanged Barker’s end-note numbers with full references in-line.)

Immigration posed a threat because it meant “aliens” would destroy the “homogeneity” of the insiders. Enoch Powell was a strident voice in the 1970s and proudly announced that “heroic measures” were called for: “repatriation”. The justification: “human nature”.

They would indeed be heroic measures, measures which radically altered the prospective pattern of our future immigration, but they would be measures based on and operating with human nature as it is, not measures which purport to manipulate and alter human nature by laws, bureaucracy and propaganda [Powell, Enoch. ‘Speech to Stretford Young Conservatives,’ in Daily Telegraph, 22 January 1977].

And here we have reached the core of the new racism. It is a theory of human nature. Human nature is such that it is natural to form a bounded community, a nation, aware of its differences from other nations. They are not better or worse. But feelings of antagonism will be aroused if outsiders are admitted. And there grows up a special form of connection between a nation and the place it lives: ‘Britain is not a geographical expression or a New-World territory open to all comers with one foot in their old home and one in their new. It is the national home and birthright of its indigenous peoples’ [Sherman, ‘Why Britain . . .’ ]. It is becoming clear that expressions of this sort are not just rhetoric, but rhetoric whose emotional content is warranted by an emergent theory.

(Barker, 21)

“Nothing racist”, goes the idea, because it only being kind to the foreigners, too! Barker continues:

Foreigners too have their natural homes. Stopping immigration is being kind to them as well. When we consider the East African Asians, for example, it would be kinder to stop them coming here; after all ‘what would have been more natural than for them to quit their Diaspora and return to help build their independent homelands, Mother India, Pakistan, Bangladesh?’ [Sherman, ‘Why Britain . . .’ ]. John Page represented this point of view in Parliament: ‘I fail to see’, he argued, ‘how the natural home of an ex-Malawi Goan can be Harrow West’ [Hansard. House of Commons Official Report, vol. 914, no. 137, Monday 5 July 1976 p. 1077]. Your natural home is really the only place for you to be; for that is something rooted in your nature, via your culture. ‘Parliament can no more turn a Chinese into an Englishman than it can turn a man into a woman’, wrote Sherman [‘Why Britain . . .’ ].

Barker challenges this deployment of the “natural home” idea: Continue reading “Understanding Racism (3) — The New Racism and Commonsense”

Jason Burke discusses the most recent UN report on the ISIS threat in The Guardian, New wave of terrorist attacks possible before end of year, UN says — UN report warns threat from Islamist extremist groups remains high

Jason Burke discusses the most recent UN report on the ISIS threat in The Guardian, New wave of terrorist attacks possible before end of year, UN says — UN report warns threat from Islamist extremist groups remains high

The UN report’s summary:

With the fall of Baghuz, Syrian Arab Republic, in March 2019, the geographical so-called “caliphate” of Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)a has ceased to exist and the group has continued its evolution into a mainly covert network. Its leadership is primarily in Iraq, while its centre of gravity remains in Iraq, the Syrian Arab Republic and areas of the immediate neighbourhood. The leadership aims to adapt, survive and consolidate in the core area and to establish sleeper cells at the local level in preparation for eventual resurgence, while using propaganda to maintain the group’s reputation as the leading global terrorist brand – the “virtual caliphate”. When it has the time and space to reinvest in an external operations capability, ISIL will direct and facilitate international attacks in addition to the ISIL-inspired attacks that continue to occur in many locations around the world.

Al-Qaida . . . remains resilient, although the health and longevity of its leader, Aiman Muhammed Rabi al-Zawahiri (QDi.006), and how the succession will work are in doubt. Groups aligned with Al-Qaida are stronger than their ISIL counterparts in Idlib, Syrian Arab Republic, Yemen, Somalia and much of West Africa. The largest concentrations of active foreign terrorist fighters are in Idlib and Afghanistan, the majority of whom are aligned with Al-Qaida. ISIL, however, remains much stronger than Al-Qaida in terms of finances, media profile and current combat experience and terrorist expertise and remains the more immediate threat to global security.

The most striking international developments during the period under review include the growing ambition and reach of terrorist groups in the Sahel and West Africa, where fighters aligned with Al-Qaida and ISIL collaborate to undermine fragile national jurisdictions. The number of regional States threatened with contagion from insurgencies in the Sahel and Nigeria has increased. The ability of local authorities to cope with terrorist challenges in Afghanistan, Libya and Somalia remains limited. Meanwhile, the Easter Sunday attacks in Sri Lanka show the continuing appeal of ISIL propaganda and the risk that indigenous cells may incubate in unexpected locations and generate a significant terrorist capability. These and other ISIL attacks on places of worship, alongside the attacks in Christchurch, New Zealand, of March 2019, offer a troubling narrative of escalating interfaith conflict.

The related issues of foreign terrorist fighters, returnees, relocators and detainees in the conflict zone have become more urgent since the fall of Baghuz. Member States also report pressing domestic security concerns, including with regard to radicalization in prisons and releases of terrorist prisoners, while only a few have the expertise and capacity to manage this range of counter-terrorist challenges successfully.

The full report:

In a former life many years ago I learned was taught a great lesson by a junior girl in another part of our work area who had to process some of our work outputs. She was obviously being driven mad by our failure to follow some simple procedures we’d no doubt been told to apply many times before, so she sent us all an email that began, “Naughty cataloguers, . . . ” That introduction was so disarming, it set us all in a positive frame of mind to meekly accept the “blasting” that came our way in a form of collegial correction.

We weren’t trolls or vicious jerks but that lesson came to mind again when I read the following news item: Twitch viewers harassed Aussie streamer PaladinAmber. She clapped back in the best way

The first time she called someone out happened by accident.

“Everyone just went crazy. They were like ‘this is exactly what we want on the news’. And I was like, we can absolutely do this every time,” she said.

“Comedy is the best way to deal with this because people will really prefer a slap on the wrist better if it comes with a giggle.”

There’s proof in the pudding too. Wadham says some of the trolls have even apologised after being called out.

. . . .

“I didn’t think people would appreciate somebody being so outspoken and obnoxiously loud about it,” she said.

“It’s [trolling] such a common occurrence. To have so many people going ‘oh yeah me too, but I wouldn’t say anything so thank you’, it’s just a little bit humbling.”

While it’s worked for her, Wadham is adamant no-one should have to confront online harassment like this if they don’t feel equipped to do so.

Dr Raynes-Goldie agreed, and highlighted how tricky it can be to push back.

“How do you make change in the world but also take care of yourself? Because it’s quite exhausting,” she said.

For Wadham, it’s by shining a light on the worst behaviour on the internet, one fake infomercial or breaking news segment at a time.

And all of that leads to this:

Produced, written and presented by Ahmed Kaballo —

https://youtu.be/M4nTmamhaWE

Let’s move from France in the 1970s and 80s to the USA, specifically Los Angeles, in the 1960s. In this post I address another frequently cited work in the subsequent literature:

In the previous post we saw cultural racism emerging in Europe; in this post we look at Sears and Kinder study what is termed symbolic racism. Symbolic. It sounds innocuous, doesn’t it. Not real. But that’s far from its intended meaning.

The occasion of the study by Sears and Kinder was change in Los Angeles and southern California in “rolling back the generous Democratic liberalism of the early 1960’s and replacing it with a tense and preoccupied conservatism” with the victory of Ronald Reagan (p. 52). My interest and focus is on understanding what lies behind the term “symbolic racism”.

Compared with the 1950s the dominant views and attitudes towards blacks among voters in Los Angeles by 1970 were racially liberal.

Respondents do not believe in racial differences in intelligence, and there is virtually no support for segregated schools, segregated public accommodations, or job discrimination. Moreover, most of the sample recognizes the reality problems that blacks face in contemporary American society. They perceive Negroes as being at a disadvantage in requesting services from government, in trying to get jobs, and, in general, getting what they deserve. And they feel that integration can work: they feel the races can live comfortably together. . . .

No doubt they feel rather moral on racial grounds and would hotly deny the contention that they are “white racists.” Indeed, they seem to have learned quite thoroughly those moral lessons conventionally taught a decade or two ago, and they represent that way of thinking rather well. It is just that they are ten or fifteen years out of date now. The attitudes that characterized a “racial liberal” in the middle 1950’s are not enough to keep one from being perceived as a “racist” in 1970. (p. 63)

Nonetheless, despite being “racial liberals” by the standards of the 1950s, it was still discovered that

racism was the single most important predictor of mayoralty voting in our survey.

So what is meant by racism? Sears and Kinder distinguish four types of racial attitudes. Continue reading “Understanding Racism (2) – Symbolic Racism”

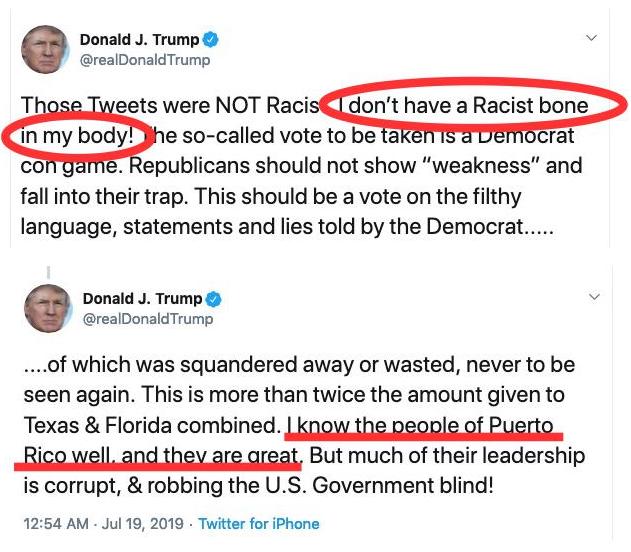

When I read Trump’s tweets. . . .

I was reminded of Brenton Tarrant’s words in his manifesto, The Great Replacement:

Brenton Tarrant, you will recall, was the murderer of 51 Muslims in Christchurch, New Zealand. He declared that he had no ill-will towards any race on earth. So long as they stayed in their “natural” borders.

Ever since I posted Strategies of Denials of Racism back in early June I have been trying to get a better handle on the subject. Islam is not a race, of course, so how does anti-Muslim sentiment get mixed up in a discussion of racism? Is it fair or just to brand as a racist someone who feels no ill-will to any other race, does not look down with loathing on another race as if they are in any sense inferior but respects them as “different but equal”?

Since early June I have read a fair amount about racism since the Second World War, and especially since the 1960s and 1970s, and had been toying with the idea of bringing a lot of that reading together for a single post. But now that the time has come I have decided to post about it an easier way. I’ll introduce one by one some of the core readings of mine and over time bring key points together into more integrated discussions.

I begin with an old one, but a good starting point nonetheless:

Taguieff surveys the way one particular part of the New Right movement in France (the Club de l’Horloge) positioned itself with new arguments that were designed to dissociate itself from the crude racist hatreds of the past (Hitler had given that sort of racism a bad name, after all), from state authoritarianism, and from fascism, and to even throw those labels back on to their left-wing, socialist and democratic opponents. In this post I focus only on the arguments relating to racism.

Traditional anti-racist groups in France were targeted by the New Right as being “anti-French, anti-Western, or anti-White” racists who supported the enemies of France, the West, and White nations. Other New Right factions (e.g. Groupement de Recherche et d’Etudes pour la Civilisation Européene, GRECE) joined with the Club de l’Horloge to reverse the traditional understanding of how racism was defined. Differences, racial and cultural differences, were eulogized.

This praise of difference was reduced to the claim that true racism is the attempt to impose a unique and general model as the best, which implies the elimination of differences. Consequenlty, true anti-racism is founded on the absolute respect of differences between ethnically and culturally heterogeneous collectives. The New Right’s “anti-racism” thus uses ideas of collective identities hypostatized as inalienable categories. (p. 111, my own bolding in all quotations)

Conversely, the racist was now defined as the one who appeared to want to “deny” or “erase” differences between the races, even allowing for a multicultural society where differences were supposedly compromised. Multiculturalism was thus, in effect, branded as “racist” — the view that genuine racial differences should (supposedly) be somehow eliminated.

In the 1970s the “right to be different” was a slogan deployed by the Left in the call for respect for minorities. In the 1980s the same slogan was appropriated by the New Right to mean something different: to claim the right for whites to be different from blacks and for those not belonging to the traditional European culture to be sent back to their ancestral homelands.

Hence in the early 1980s the French New Right presented itself as

against all forms of racism, without any bad conscience or self-hate

Continue reading “Understanding Racism (1) – Cultural Racism”

Excerpt from Aljazeera’s How close are Iran and the US to war?

Excerpt from Aljazeera’s How close are Iran and the US to war?

The “real deterrent” in the current situation was the fact “the Iranians were able to down the most advanced American drone using stealth technology with an Iranian-made surface-to-air missile,” he said, adding that Trump may have stood down because he recognised any Iranian response to a US attack would be “relentless and disproportionate”.

In such a scenario, Iran was also likely to target US allies in the region, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, where the drone that was shot down reportedly took off from.

“I think it would be an enormous miscalculation on the part of the Americans to assume that the Iranian response to any strike would be limited.

“It will be larger than the initial strike, it will be disproportionate, and it will be relentless. And it will not only target the aggressor, it will target those countries – like the United Arab Emirates or perhaps Saudi Arabia – that allowed the US to carry out this attack.”

Mahjoob Zweiri, director of the Gulf Studies centre at Qatar University, said Trump’s actions towards Iran are designed to appeal to his support base in the US ahead of the 2020 presidential elections.

“He has done what will make [his base] happy, he has withdrawn from the [nuclear] deal, he imposed sanctions, he basically made sure the economy of Iran was really falling apart. He has done everything he has promised his base.

“Trump’s main focus is a second term. If any military action against Iran will affect this badly, he will never do it.”

Zweiri said the escalating series of incidents in the Gulf may be an Iranian ploy to pile up pressure on the international community to act and protect Tehran from US sanctions.

“They want to push more for the international community to act, to mediate, to push, to pressure the United States, to have a dialogue because this status quo is collapsing their economy and will have serious ramifications on the stability of the regime in Iran.

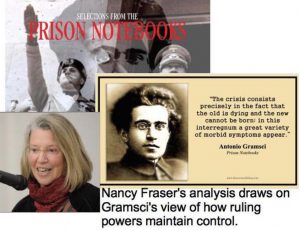

This is the final post in the series covering Nancy Fraser’s article, “From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump—and Beyond” that was published in the American Affairs Journal in 2017. Previous posts so far:

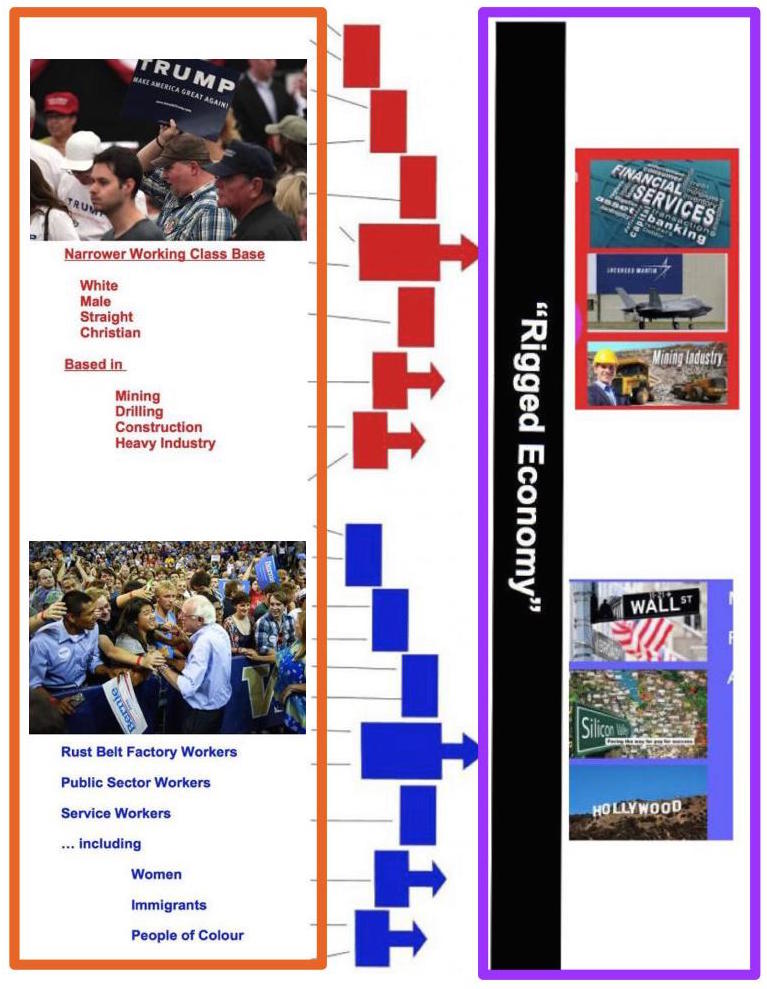

We concluded post #4 on the depressing note that the most logical solution to address the failures of both Obama and Trump is for the mainstream working and middle classes to unite against their real enemy, the powers that are responsible for their current plights of home losses, job losses, insecure and low paid work, ballooning debts of all kinds, . . . , to unite: but currently they are divided between the populists on the Bernie Sanders side of the fence and the populists backing Trump and the two sides hate each other.

We concluded post #4 on the depressing note that the most logical solution to address the failures of both Obama and Trump is for the mainstream working and middle classes to unite against their real enemy, the powers that are responsible for their current plights of home losses, job losses, insecure and low paid work, ballooning debts of all kinds, . . . , to unite: but currently they are divided between the populists on the Bernie Sanders side of the fence and the populists backing Trump and the two sides hate each other.

So, what does Nancy Fraser suggest?

Her most critical message is for the progressives. Stop being so damn moralizing and condescending to the Trump-ists. Acknowledge that the problems are systemic. Once you start from the position that racist attitudes are genetic and that the only proper response is to condemn the attitudes of “the deplorables” then you start from a losing position.

The message, rather, is to keep one’s eyes on the real enemy, on those who are primarily responsible for the current plight of us all who subsist and struggle beneath the corporate elites.

If that doesn’t satisfy your moral instincts then try to understand that the racist issues are bound up with the class issues and a bit of clarity as to causes and background will help heal wounds or at least lower barriers sufficiently to form some type of alliance against the real cause of what we (globalization means the problem extends beyond the U.S.) are facing.

The first thing that needs to be done is to recognize what the ruling progressive neoliberal economic elite forces have done. Recall Gramsci (see posts 1 and 4). They have used the rhetoric of feminism, anti-racism, green-causes, to win recognition for themselves as the saviours of all that is good. What is needed, Nancy Fraser says, is a “strategy of separation”. Acknowledge the seduction of the corporate powers and make a clean break.

First, less-privileged women, immigrants, and people of color have to be wooed away from the lean-in feminists, the meritocratic anti-racists and anti-homophobes, and the corporate diversity and green-capitalism shills who hijacked their concerns, inflecting them in terms consistent with neoliberalism. This is the aim of a recent feminist initiative, which seeks to replace “lean in” with a “feminism for the 99 percent.” Other emancipatory movements should copy that strategy.

That’s the first. There’s a second. Certainly there are down-to-the-core ethnonationalists and racists. But does that core really represent all in that orbit? Or at least, at least, are not many of those Trump-ists still open to joining forces with those in the camp from which many of them defected in 2015 — disillusioned Sanders’ supporters?

Second, Rust Belt, southern, and rural working-class communities have to be persuaded to desert their current crypto-neoliberal allies. The trick is to convince them that the forces promoting militarism, xenophobia, and ethnonationalism cannot and will not provide them with the essential material prerequisites for good lives, whereas a progressive-populist bloc just might. In that way, one might separate those Trump voters who could and should be responsive to such an appeal from the card-carrying racists and alt-right ethnonationalists who are not. To say that the former outnumber the latter by a wide margin is not to deny that reactionary populist movements draw heavily on loaded rhetoric and have emboldened formerly fringe groups of real white supremacists. But it does refute the hasty conclusion that the overwhelming majority of reactionary-populist voters are forever closed to appeals on behalf of an expanded working class of the sort evoked by Bernie Sanders. That view is not only empirically wrong but counterproductive, likely to be self-fulfilling.

Recall that it is “progressive neoliberalism” that the Trump supporters have opposed. That

Moral condemnation of racists, homophobes, climate change deniers, the anti-abortionists and Christian fundamentalists, of those on the “regressive populist” side, is bound up with the recognition values of the corporate elites of the progressive neoliberals. Recall the Gramscian analysis in posts one and four. By pitting one group against the other they effectively deflect attention from their own role in the real problems inflicted on both sides.

Moral condemnation of racists, homophobes, climate change deniers, the anti-abortionists and Christian fundamentalists, of those on the “regressive populist” side, is bound up with the recognition values of the corporate elites of the progressive neoliberals. Recall the Gramscian analysis in posts one and four. By pitting one group against the other they effectively deflect attention from their own role in the real problems inflicted on both sides.

[I]t is counterproductive to address [concerns about racism, sexism, homophobia, Islamophobia, and transphobia] through moralizing condescension, in the mode of progressive neoliberalism. That approach assumes a shallow and inadequate view of these injustices, grossly exaggerating the extent to which the trouble is inside people’s heads and missing the depth of the structural-institutional forces that undergird them.

Fraser addresses race in a little detail to illustrate the point. Yes, hating blacks is bad, of course. But notice, think, recall . . .

In this period, black and brown Americans who had long been denied credit, confined to inferior segregated housing, and paid too little to accumulate savings, were systematically targeted by purveyors of subprime loans and consequently experienced the highest rates of home foreclosures in the country.

In this period, too, minority towns and neighborhoods that had long been systematically starved of public resources were clobbered by plant closings in declining manufacturing centers; their losses were reckoned not only in jobs but also in tax revenues, which deprived them of funds for schools, hospitals, and basic infrastructure maintenance, leading eventually to debacles like Flint — and, in a different context, the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans.

Finally, black men long subject to differential sentencing and harsh imprisonment, coerced labor and socially tolerated violence, including at the hands of police, were in this period massively conscripted into a “prison-industrial complex,” kept full to capacity by a “war on drugs” that targeted possession of crack cocaine and by disproportionately high rates of minority unemployment, all courtesy of bipartisan legislative “achievements,” orchestrated largely by Bill Clinton.

We get the picture. The race problem is an institutional problem. We need to target the real causes. Don’t fall back on the losing strategy of moralizing our would-be allies.

The focus, the slogans, the memes etc,

must highlight the shared roots of class and status injustices in financialized capitalism.

It’s a conceptual change that’s needed:

Conceiving of that system as a single, integrated social totality, it must link the harms suffered by women, immigrants, people of color, and LGBTQ persons to those experienced by working-class strata now drawn to rightwing populism. In that way, it can lay the foundation for a powerful new coalition among all whom Trump and his counterparts elsewhere are now betraying — not just the immigrants, feminists, and people of color who already oppose his hyper-reactionary neoliberalism, but also the white working-class strata who have so far supported it.

The entire working class must be brought together as a counter to the forces currently exploiting and bleeding them. Fraser sees the initiative for such a shift coming from the progressive populists, those who are currently alienating their potential allies by subjective moralizing instead of targeting the objective causes of their shared problems.

The capitalist system is like a tiger eating its own tail, Fraser suggests. It is destroying the environment on which it depends, it is withering the working and middle class base on which it also depends, . . . it cannot continue. But before it ruins us all a new counter-weight, a new hegemonic bloc needs to challenge it — for the sake of all.

Nancy Fraser’s article can be read in full at https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2017/11/progressive-neoliberalism-trump-beyond/

I have tried to make some of its key points clear, hopefully without sacrificing too much of the original.

Fraser, Nancy. 2017. “From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump—and Beyond.” American Affairs Journal 1 (4): 46–64. https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2017/11/progressive-neoliberalism-trump-beyond/

It’s always good when traveling to keep an eye out for opportunities to explore something off the usual tourist trail and this trip I found out how things work inside a Thai hospital. All the staff, medical and administrative, wear the most stylish uniforms and do everything with utmost professionalism. My key contact there told me he had been trained for 6 years in Sydney, Australia. But slightly veering off the usual day-to-day experiences opens one’s eyes to little things where values and expectations differ in sublte ways from what we expect in Australia and probably many other white English speaking countries.

For one, when my contact (who is responsible for international visitors to the hospital) introduced the nurse who would be the one responsible for my immediate care he introduced her with “This most beautiful lady’s name is ….” Things like that immediately hit one in a way to remind us Westerners at least that we have a whole different social thing going on with feminism and how men have to learn to do things differently from the way they were done in the old days. At least where I worked — in public universities and libraries — such a manner of addressing a woman in a professional situation would always be considered inappropriate. (He spent 6 years in Sydney but the Thai customs never left him.)

Then there was this. The day I was discharged I was being wheeled out and for the first time I saw the walls around me and not just the ceilings …. now I don’t know about other Anglo-Saxon countries, but I have a feeling that we would be most unlikely to be confronted with the following cartoon figure in such a place, (or is my experience of hospital murals way too limited?)

Actually before I went to the hospital I was looking for an ordinary doctor somewhere and following helpful directions I came to an area where there were sort of nurse-like-uniformed girls standing outside a shop handing out flyers, presumably to encourage people to enter — I wasn’t sure if it was actually a doctor’s surgery so I looked in and asked the woman I thought was the receptionist at the front desk for a doctor and she replied that she was the doctor and asked how she could help. There was a quick diagnosis over the counter …. But I will not want to leave the impression that that’s how all doctors here operate! Nor would she always service all clients that way.

Anyway, it was all a very interesting experience, something different, which I always look forward to. Oh, one more detail. When being discharged I was handed a form to fill out. It consisted of dozens or questions — but all in Thai — which I learned were asking me how I felt about their service, would I ever like to use them again, would I recommend them to someone else, that sort of thing, I think. I scarcely know the Thai alphabet so I left it aside.

And while talking of different things, here are a couple more.

I was in an outlying “suburban” area of Bangkok (though it was more like a city centre in many places in Australia) and was waiting responsibly at the lights to cross the road. When they turned green to signal me across I stepped out but not a damn car or motor bike seemed to notice that they had a bloody red light! There must have been about a dozen cars and bikes that just kept on driving through and weaving their way around me. It was a stimulating experience, that’s for sure. Usually cars stop at red lights, even here. But obviously not always. And when I reached the other side I passed two police officers nonchalantly walking back to their vehicle with their purchased lunches.

Anyway, I went into a chemist and asked for something and they searched frantically everywhere for me but couldn’t find what I wanted, so with their smiling apologies I left. I must have been about 50 metres down the street when I heard a woman shouting. She reached me to show me that she had finally found what I was asking for. It wasn’t quite what I was wanting but I couldn’t disappoint her after making such an effort so I returned with her and made the 39 baht ($A2) purchase.

Beer is not such a big deal here. Every shop sells it and sometimes the staff helpfully add a straw before you take it away. I know you won’t believe me so I took a photo to prove it’s true.