edited and added TLT quote Jan 26, 2010 @ 20:05

I think of myself as neither a “Jesus mythicist” nor a “Jesus historicist”, but as someone interested in exploring the origins of Christianity. Whether the evidence establishes a historical Jesus at its core, or an entity less tangible, then so be it. Nonetheless, I cannot deny the importance and implications of the question.

Two things that bug me about much of the historicist position are:

- many of its interpretations of the evidence are grounded in circular reasoning

- many of its arguments are rhetorical and/or built on the fallacy of incredulity (aka “the divine fallacy“)

There are things that bug me about some mythicist arguments, too. But here I want to share the first of a series of responses I am making against the historicist position as summed up by a contributor on a Richard Dawkins website discussion forum.

In summary:

(i) [Jesus] existed

The idea that the stories about him are based on a historical figure is the most parsimonious explanation of how they arose, since the alternatives require repeated suppositions to explain away key elements in the evidence (eg all those “maybes” required to make references to his brother etc disappear).

This would be true IF the earliest evidence is for a more human Jesus, with the later evidence demonstrating an emerging divinization of this person until he eventually reaches co-creator and sustainer of the universe god status.

But the evidence we do have is actually the reverse of the above. The earliest evidence — such as an early hymn quoted by Paul (Phil. 2) — describes Jesus as equal with God, who had a brief temporary transformation to look like a human in order to be killed to effect a theological saving destiny for humankind, and was restored to the highest God-status and given the new name of Jesus, and worshiped by all as a reward.

. . . . Christ Jesus:

Who, being in very nature God,

did not consider equality with God something to be grasped,

but made himself nothing,

taking the very nature of a servant,

being made in human likeness.

And being found in appearance as a man,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to death—

even death on a cross!

Therefore God exalted him to the highest place

and gave him the name that is above every name,

that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father.

Paul’s Jesus as referenced in the rest of his letters hews to the same identity. Jesus for Paul is the Spirit and Wisdom of God, a God-head figure of worship, whose exalted heavenly status is the honour bestowed on him for his descent into at least some form of flesh for the purpose of crucifixion.

It is the later evidence (among the gospels) that seeks to humanize Jesus. In Mark, he is said to become possessed by the Son of God spirit, lose his temper and need a couple of shots at healing a blind man. In Luke and Acts, his death is described as that of a merely righteous human martyr. A later copyist even added a scene with him sweating blood.

The most parsimonious way to describe this trajectory of the actual evidence is to see Jesus as beginning his history as a heavenly figure whose temporary appearance in the form of a man became the subject of later elaborations.

He is mentioned by Josephus twice and by Tacitus once and the arguments required to make these clear references in two independent sources disappear require, once again, a small hill of suppositions and contrived arguments.

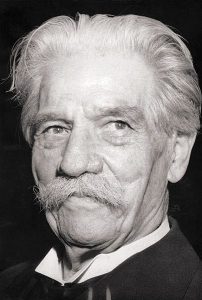

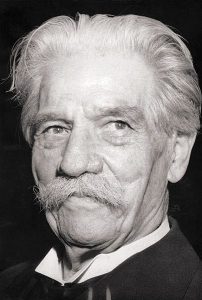

On the contrary, the contrived arguments are those that have emerged since the Second World War when many things changed. Prior to that time the scholarly consensus — a consensus that included names like Albert Schweitzer and Walter Bauer — was that these texts are worthless as testimony for the historicity of Jesus. So to accuse anyone who dismisses the value of the Josephus evidence of resorting to “contrived arguments” is to insult some of the greatest names in the history of biblical scholarship.

On the contrary, the contrived arguments are those that have emerged since the Second World War when many things changed. Prior to that time the scholarly consensus — a consensus that included names like Albert Schweitzer and Walter Bauer — was that these texts are worthless as testimony for the historicity of Jesus. So to accuse anyone who dismisses the value of the Josephus evidence of resorting to “contrived arguments” is to insult some of the greatest names in the history of biblical scholarship.

Sometimes intellectual changes reflect broader cultural developments, and this seems to be one case in point. It appears to coincide with the shift in scholarly consensus to exonerate or excuse Judas, and other scholarly research designed to emphasize the Jewishness of Jesus. Western guilt over past anti-semitism has been proposed as one explanation for some of these scholarly shifts. I suspect something similar at work in finding ways to bring the Jewish historian Josephus and Jesus together.

The stories about him contain elements which are clearly awkward for the gospel writers (his origin in Nazareth, his baptism, his execution) and which they try, largely unsuccessfully, to explain away or which they downplay or remove. These elements are awkward because they don’t fit the expectations of who and what the Messiah was, yet they remain in the story.

Apart from the subjectivity of deciding if a narrative detail is “clearly awkward”, this argument rests on a false premise.

The fact is that there is no evidence for some general expectation among Jews for any particular type of Messiah at all in the period discussed.

In a review of the most detailed discussions of the idea of the Messiah among Jews of the Second Temple period, The One Who Is to Come by Joseph A. Fitzmyer, Jeffrey L. Staley writes:

There is no serious attempt to place messianism within the broader matrix of social history. There is no interaction with, say, Richard Horsley or John Dominic Crossan’s work on social banditry and peasant movements (Bandits, Prophets, and Messiahs: Popular Movements in the Time of Jesus; The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant). One might then ask of Fitzmyer what communities he thinks are reflected in his textual study. If, as many have suggested, only 5 percent of the ancient Mediterranean population could read and write, then what segment of the population is reflected in Fitzmyer’s analysis? Is his “history of an idea” representative of Jewish belief at large, or does it represent only a small segment of the population? Does Fitzmyer’s study of the “history of an idea” reflect only the elites’ mental peregrinations, which are largely unrelated to the general masses? And what difference, if any, would his answer to this question make to this “history of an idea”?

Thomas L. Thompson, The Messiah Myth, has discussed in detail the literary nature of this messianic ideal (a literary construct that extends beyond a Jewish literate class, and stretches across cultural and ethnic groupings from Egypt to Mesopotamia), and finds no correlation of it among popular Jewish culture before the second century c.e.:

Nevertheless, to make an argument that a specific theme belongs to the earliest sources of the gospels is not sufficient to associate it with history. The interrelated themes that have brought Weiss and Schweitzer — and the scholarship following them — to speak of Jesus as an apocalyptic prophet do not reflect religious movements of the first century BCE. The thematic elements of a divinely destined era of salvation, a messianic fullness of time and a day of judgment bringing about a transformation of the world from a time of suffering to the joys of the kingdom are all primary elements of a coherent, identifiable literary tradition, centuries earlier than the gospels, well-known to us from the Bible and texts throughout the entire Near East. (p. 28)

There may also be some relevance here in Jon D. Levenson’s case that at least some not insignificant number of Jews in the Second Temple period coming to embrace a theology involving salvation through an atoning sacrifice of Isaac, as I have discussed in posts archived here.

This makes perfect sense if the gospel writers are trying to make a historical figure fit the Messianic expectations and some elements in his story simply don’t fit well. But it makes no sense at all if they are making him up or his story simply arose out of the expectations. If that were the case his story would fit the expectations very neatly and these awkward elements wouldn’t exist.

This is a repeat of the standard argument among the biblical studies faculties to establish the historicity of everything from the baptism of Jesus to his resurrection. The logical structure of the argument is elsewhere described as “the divine fallacy”. More formally it is listed among other fallacies as the fallacy of (personal) incredulity.”

N.T. Wright and other mainstream academics join with apologists in using this logic to prove the historicity of the resurrection on the basis that the “embarrassing” and “uncomfortable” and “awkward” fact is that mere untrustworthy women were the first witnesses.

To paraphrase the way it goes:

This makes perfect sense if the gospel writers are trying to speak honestly about the historical resurrection of Jesus and some elements in their story simply don’t fit well.

It makes no sense at all if the gospel writers are trying to make up a story about the resurrection.

If that were the case, they would never have said women were the first witnesses.

Everyone knew that women’s testimony was worthless in those days.

So it makes perfect sense if the gospel writers were writing about a historical event.

Others use the same logical fallacy to prove God, or creation science, or psychic powers:

How else can you explain this of that fact?

God/creationism/the tooth fairy are the only explanations that make sense of the evidence!

No other explanation makes any sense!

That such fallacious reasoning underpins so much of historical Jesus studies seems to escape notice surely can only be explained in the context of its cultural familiarity. (Trying to avoid slipping into the same fallacy here. :-/ )

(The original context of the summary cited here, by Tim O’Neill, can be found here.)

“F” is for “False Dilemma”

Image by BinJabreel (Is on Hiatus) via Flickr

(The original context of the summary cited here, by Tim O’Neill, can be found here.)

Like this:

Like Loading...

No. At least not in the time of Bar Kochba‘s revolt against Rome, 132-136 ce.

No. At least not in the time of Bar Kochba‘s revolt against Rome, 132-136 ce.