This post concludes the series of posts covering Strelan’s argument that Mark’s disciples are based on Enoch’s Fallen Watchers.

This post concludes the series of posts covering Strelan’s argument that Mark’s disciples are based on Enoch’s Fallen Watchers.

The Mount of Olives was “sacred space” for the author of the Gospel of Mark. This was the place where Jesus took Peter, James and John into to the revelation of the mystery of the signs — Mark 13:3 (the Little Apocalypse/Olivet Prophecy).

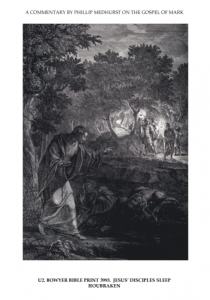

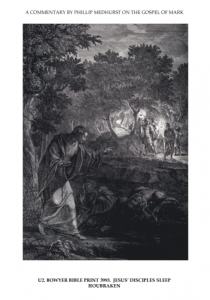

Called to Watch, but “like children of the earth” fall asleep

So for the fourth time (see previous post for the previous 3 times) Jesus takes Peter, James and John aside to be “with him” – (14:33). These three are thus appointed to stay awake with Jesus, just as Watchers are ordained to be awake in the presence of the Lord day and night.

Faithful watchers do not sleep.

Enoch 39:12-13

12. Those who sleep not bless Thee: they stand before Thy glory and bless, praise, and extol, saying: “Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord of Spirits: He filleth the earth with spirits.”‘ 13. And here my eyes saw all those who sleep not: they stand before Him and bless and say: ‘Blessed be Thou, and blessed be the name of the Lord for ever and ever.’

Enoch 40:2

2. And on the four sides of the Lord of Spirits I saw four presences, different from those that sleep not

Enoch 71:7

7. And round about were Seraphin, Cherubic, and Ophannin:

And these are they who sleep not

And guard the throne of His glory.

Here on the Mount of Olives Jesus addresses his head disciple by his real name, Simon, (not “Peter”), “thus suggesting the ambiguity of their relationship”. This is the same Simon who, in Mark 1:36 (as addressed in my previous and earlier posts) had, along with those “with him”, pursued (with hostile intent) Jesus, to turn him away from the desert place where he had gone to pray.

Now again we find Jesus alone praying. This time, however, Peter lacks the strength to pursue him aggressively, and falls asleep instead. The disciples, like the “children of the earth”, fall asleep. Jesus exhorts them to “watch and pray” (14:38) lest they enter temptation.

Watching and praying are the duties of Enoch’s Watchers and angels in general. Their task is to intercede for humans and bring their prayers to God — e.g. 1 Enoch 9:4-9; 15:1-2; Tobit 3:16, 12:12, 15.

Jesus alone is the true “son of the father” (14:36), or son of heaven. His disciples show themselves to be, instead, sons of the earth.

Temptation and Fall Continue reading “The Fall of Jesus’ Disciples as Enoch’s Watchers”

Like this:

Like Loading...