On 14th January I posted How Historians Work – Lessons for Historical Jesus Scholars in which I demonstrated that at least some biblical scholars are unaware of normal historical practices by quoting key sections from works recommended to me by Dr McGrath. On 16th January Dr. James F. McGrath, Clarence L. Goodwin Chair in New Testament Language and Literature at Butler University, responded by accusing me of being a fool, either ignorant or obtuse on the one hand or wilfully misrepresenting and wishing to deceive readers whom I believe are gullible and foolish on the other.

Unfortunately Dr McGrath’s reply only further convinced me that he has not read both books in question even though he recommended them to me — though he does appear to have at least read sections (only) of one of them — and that his smearing of my character and intelligence is unwarranted.

Dr McGrath began his reply with:

I sometimes wonder if mythicists realize when they are making fools of themselves. If they do, then they are presumably akin to clowns and comedians who provide a useful service in providing us with entertainment. If they are unintentionally funny, then their clowning around in some instances may include misrepresentation of others which, however ridiculous, requires some sort of response.

Presumably this sort of ad hominem is intended as filler in place of reasoned responses to virtually the whole of the arguments and demonstrations of my post since he repeats such accusations often while never engaging with all but a couple of my points, and even those only tangentially.

Dr McGrath then lands another character attack that he says he will not deliver or will ignore so I will ignore that for now, too — although I did respond to it on his blog at the time.

So to the main point:

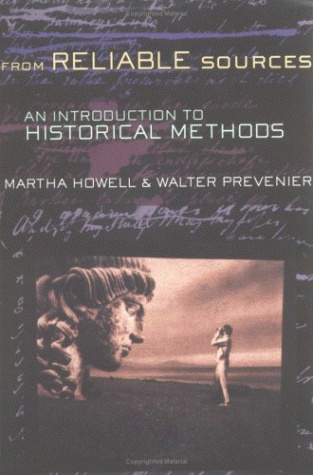

But on the misrepresentation of Vansina, and of Howell and Prevenier, a few brief points are in order, which I suspect will show clearly to anyone interested that Godfrey either is either failing to comprehend Vansina, Howell, and prevenier, or is willfully misrepresenting them.

This introduction at the very least leads me to expect that Dr McGrath will demonstrate by quoting Vansina and Howell and Prevenier Continue reading “Historical Jesus Scholarly Ignorance of Historical Methods”