.

| Continuing the series on Thomas Brodie’s Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discovery, archived here.

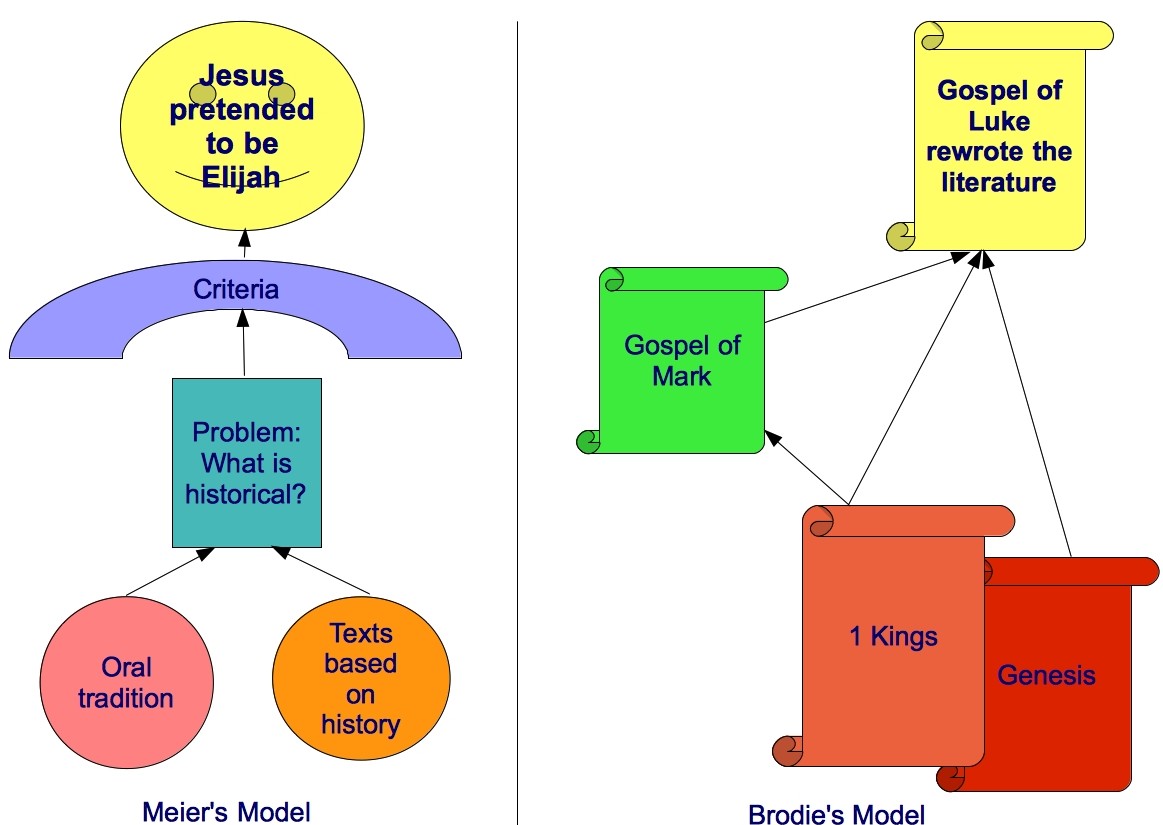

This post concludes chapter 17 where Brodie is analysing John Meier’s work, A Marginal Jew, as representative of the best that has been produced by notable scholars on the historical Jesus.

|

Brodie’s discussion of the four Greco-Roman source references to Jesus is brief.

Brodie’s discussion of the four Greco-Roman source references to Jesus is brief.

Tacitus (writing c. 115 CE) writes:

Nero . . . punished with . . . cruelty, a class of men, loathed for their vices, whom the common people [the vulgus] styled Christians. Christus, the founder of the name, had undergone the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius, by sentence of the procurator Pontius Pilate (Loeb translation). (p. 167, from Annals, 15.44)

Brodie essentially repeats John Meier’s own discussion found on page 91 of volume 1 of A Marginal Jew, commenting that there is nothing here that would not have been commonplace knowledge at the beginning of the second century. (Brodie relies upon the reader’s knowledge of Meier’s work to recognize this as Meier’s own position.)

Brodie adds that Tacitus regularly used older writings and always adapted their contents to his own style. As pointed out by Charlesworth and Townsend in the article on Tacitus in the 1970 Oxford Classical Dictionary Tacitus “rarely quotes verbatim”. By the time Tacitus wrote, Brodie remarks, some Gospels were decades old and “basic contact with Christians would have yielded such information.” His information could even have been inferred from the work of Josephus.

As for Suetonius (shortly before 120), Pliny the Younger (c. 112) and Lucian of Samosata (c. 115-200), Brodie quotes Meier approvingly:

[They] are often quoted in this regard, but in effect they are simply reporting something about what early Christians say or do; they cannot be said to supply us with independent witness to Jesus himself (Marginal Jew: 1, 91). (p. 167)

| I am even more sceptical about the contribution of Tacitus. Recently I posted The Late Invention of Polycarp’s Martyrdom (poorly and ambiguously title, I admit) drawing upon the work of Candida Moss in The Myth of Persecution.

Moss shows us that it was only from the fourth century that the stories of martyrdoms and persecutions that so often dwelt luridly on the gory details of bodily torments became popular. The passage in Tacitus with its blood-curdling details of tortures fits the mold of these later stories. (Moss herself, however, does not make this connection with Tacitus.) This brings us to the late fourth-century monk Sulpicius Severus (discussed by Earl Doherty in Jesus Neither God Nor Man, p. 618-621) who supplies us with the first possible indication of any awareness of the passage on Christian persecutions in the work of Tacitus. This topic requires a post of its own. Suffice it to say here that I believe there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that this detailed passage on the cruelties inflicted on the Christians was “borrowed” from the account written by Sulpicius Severus.

|

Conclusion regarding the five non-Christian authors

Brodie thus concludes that none of the five non-Christian authors provides independent witness to the historical existence of Jesus.

None met Jesus; none claimed to have met anyone who had known him; none claimed to have met someone who knew a friend who knew someone who had known him. None supplies us with any information that is not already found in the Gospels or Acts. (Josephus even lived within walking distance of Christians in Rome.)