In Genesis 6 we read a most cryptic detail that leaves us wondering what it is all about:

And it came to pass, when men began to multiply on the face of the earth, and daughters were born unto them, 2 That the sons of God saw the daughters of men that they were fair; and they took them wives of all which they chose. . . . 4 There were giants in the earth in those days; and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bare children to them, the same became mighty men which were of old, men of renown.

5 And God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually. 6 And it repented the Lord that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him at his heart. 7 And the Lord said, I will destroy man whom I have created from the face of the earth . . .

We have been covering Russell Gmirkin’s book, Plato’s Timaeus and the Biblical Creation Accounts, but as I was poring through the background reading I found myself drawn back to the question of why the story of the flood in Genesis begins with an account of “sons of god”, or as the Hebrew also allows, “sons of gods”. Why did the Genesis author open his flood story with such a curious episode?

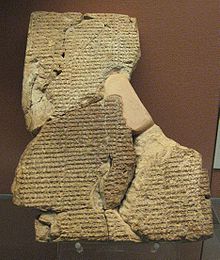

Let’s begin at the beginning — with the noncontroversial fact that Mesopotamian myth lies behind the biblical story of Noah’s flood. But let’s also examine how Mesopotamian and Biblical narratives are so very different from each other.

In Mesopotamian flood myths the gods did not use the flood to punish humankind because of its immorality or violence. No, it was not a moral judgement sent by any of the gods. It was a decision of convenience and comfort: a god was complaining of overpopulation and the resultant noise of so many people on earth keeping him awake.

The land grew extensive, the people multiplied,

The land was bellowing like a bull.

At their uproar the god became angry;

Enlil heard their noise.

He addressed the great gods,

“The noise of mankind has become oppressive to me.

Because of their uproar I am deprived of sleep. (Atrahasis myth as quoted in Hendel, 17)

Significant here is what happens after the flood. The flood marks a dividing line between two different ages:

To prevent future overpopulation, the gods take several measures: they create several categories of women who do not bear children; they create demons who snatch away babies; and . . . they institute a fixed mortality for mankind. The restored text reads: “Enki opened his mouth / and addressed Nintu, the birth-goddess, / ‘[You,] birth-goddess, creatress of destinies, / [Create death] for the peoples.'” Death, barren women, celibate women, and infant mortality are the solutions for the problem of imbalance that precipitated the flood. (Hendel 17f)

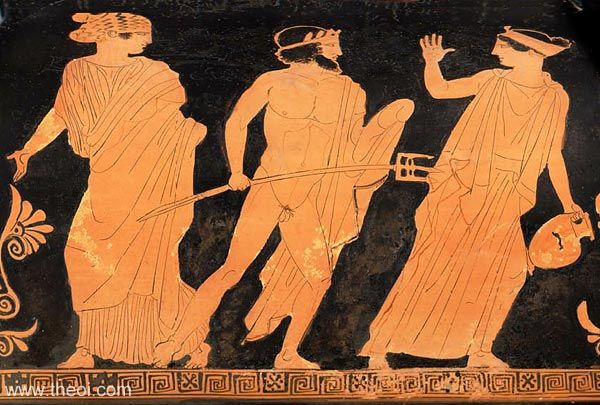

Here we find that although there were myths of great floods, the primary myth about the dividing of mythical from “historical” time was the Trojan War. And this mythical saga opened, like the Genesis flood story, with gods and mortals marrying and producing heroic figures.

In previous posts we have seen Gmirkin’s argument that the Genesis author began his flood narrative with gods marrying women under the influence of Plato’s Timaeus and Critias. What I am interested in doing here is examining the wider tradition of that same Greek myth of gods and mortals and how other accounts more directly linked this myth with the end of the primeval world. There are additional influences from this wider world of Greek myth on the Genesis author, I believe.

The Trojan War as the Divider between Mythical Time and Historical Time

Surviving Greek tales of gods living on earth with humans are compiled in a work called the Catalogue of Women. This poem begins with gods (or sons of older gods) marrying mortal women and producing heroic figures.

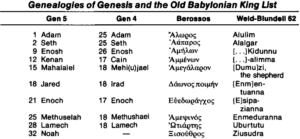

The Catalogue . . . does not begin with an account of the flood but with a remark about the union of the gods with mortal women to produce the heroes who are the subject of the Catalogue. This strongly suggests that the [biblical author] has combined this western genealogical tradition and the tradition of the heroes with the eastern tradition of the flood story. (Van Seters, 177)

In this myth the chief god, Zeus, decided to put an end to the mixing of divine and mortal races by means of war: he manoeuvred events to bring about the Trojan War that was meant to kill off the semi-divine heroes. Many of these heroes were taken to the Fields of the Blessed but the point of their demise was to re-establish a clear division between gods and humans. (There is no general moral condemnation of these heroes in Greek myth, nor, as Gmirkin stresses in his own work, is there moral condemnation against these figures in the biblical narrative.) From the time of the Trojan War the “age of myths” basically comes to an end and “real history” begins.

Returning to the question of why Genesis 6:1-4 is such a brief account (so brief the author must have assumed his readers knew the larger story), it is interesting to learn that brief synopses of longer tales are also found in Hesiod’s Catalogue of Women. This work, too, often reads much like a compendium of mere outlines of myths.

As in the Theogony, the genealogies were interspersed with many narrative episodes and annotations of greater or less extent. We can see that these narratives were often very summary; but they are there, and are an essential ingredient in the poem. A large number of the traditional myths, perhaps the greater part of those familiar to the Greeks of the classical age, were at least touched on and set in their place in the genealogical framework. Thus the poem became something approaching a compendious account of the whole story of the nation from the earliest times to the time of the Trojan War or the generation after it. We shall see when we come to study its contents more closely that its poet had a clearly defined and individual view of the heroic period as a kind of Golden Age in which the human race lived in different conditions from the present and which Zeus terminated as a matter of policy. We shall also see that he organized his material with some skill so as to convey his sense of the unity of the period in spite of the multiplicity of genealogical ramifications. (West, 3)

The first readers or audiences were expected to know the details of what could be abridged so they could maintain their focus on the larger plot.

In Greek myth, the intermarriage of gods and mortals was the opening scene of the tale that led Zeus to destroy the race of heroic demi-gods and so restore a new world with a clear division between the divine and human. These myths were anything but consistent, however, and other accounts offered a different reason for Zeus deciding to depopulate the earth through the Trojan War. One other reason was that the earth was simply becoming overpopulated. It is possible that the Greeks borrowed this idea from the Mesopotamian myth (see above where a god complains about the noise so many people were making) but it is also possible — since there is a comparable Indian myth — that the concept had a more general Indo-European origin (Hendel, 20).

So we have different motives for Zeus’s decision to destroy the old world and bring about a new one: Continue reading “Sons of God, Daughters of Men … and “Giants” — Why are they in the Bible?”