Previous posts reviewing NV’s Writing With Scripture:

- How and Why the Gospel of Mark Used Scripture — a review of Writing with Scripture, part 1

- Creating New Stories from Scripture — a review of Writing with Scripture, part 2

- To What Shall We Compare the Gospels? — a review of Writing with Scripture, part 3

- Creating Pseudo-History (and Comedy) from Scripture — a review of Writing with Scripture, part 4

Don’t look too hard to try to uncover hidden meanings in scriptural allusions in the Gospel of Mark. Those scriptural allusions may be “nothing more than” fillers to flesh out colourful story details. That’s the opening message of Nathanael Vette (NV) in his third and main chapter discussing five episodes in the Gospel of Mark.

The evangelist sometimes introduces Scripture explicitly to give readers a particular interpretation; other times Scripture is woven into the narrative more subtly. There is no consistent method in the use of Scripture.

The introductory message

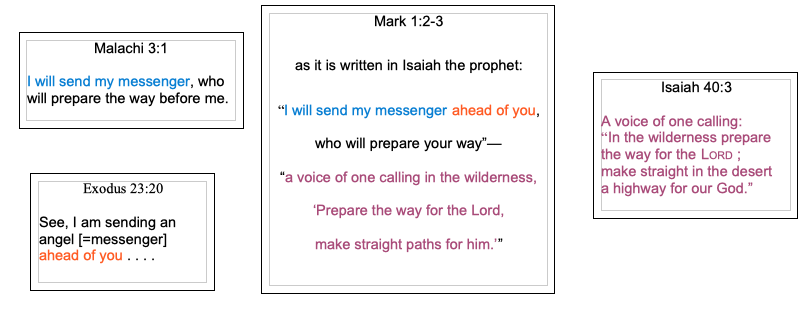

Take the opening verses of the Gospel. It is not an exact quotation from any passage in the Old Testament.

To the contrary, the prologue shows an author primarily concerned with the immediate demands of their narrative, untroubled by the precise wording of their sources, and creative in their application of them. Mark is nourished by the language of scripture more than the substance of it. (NV, 111. My bolding in all quotations)

NV guides the reader through both the Greek and Hebrew versions of the Scriptures in order to explore not only how the author may have arrived at the purported Isaianic quotation but also how to identify the one being prophesied: Elijah or the Messiah? In Malachi’s following chapter (4:5) the prophet speaks of Elijah coming before the “Day of the Lord” while elsewhere in the Gospel of Mark we learn that John the Baptist is the “Elijah to come”, yet the “messenger” in the source texts is surely a more exalted figure than a prophet. Some readers will be surprised to see that NV concludes . . .

In the final analysis, the garbled citation of LXX Isa. 40:3 and LXX Exod. 23:20 (and possibly Mal. 3:1), which is misattributed to Isaiah, is, above all, a prophecy concerning the coming of the Lord. Any reference to Elijah, if intended, is secondary to this aim. (NV, 116)

Perhaps so. Yet do we not find other studies pointing out how the Gospel of Mark is rich in ambiguities and ironies? Might not we read here another instance of Markan ambiguity rather than feel obligated to choose one or another option?

By his appearance you will know him

The Elijah-John the Baptist connection is clearer a few verses on when we read of John’s leather belt and “hairiness”, but for readers who are curious about the range of possibilities that gave rise to John’s “camel hair” garment, NV addresses a wide range of sources and manuscript languages that arguably lay behind the image. Was the author simply imagining what clothing and diet one would expect of a man of the wilderness? If this is the case then the imagery of camel’s hair, locusts and honey may be best understood as items indirectly linked to the scriptural-based setting of a wilderness mission. As for the question of the historicity of John I appreciated NV’s response to Craig Evans’ claim:

Regarding this deviation from the scriptural description, the opinion of Craig Evans is typical: ‘The reference to camel’s hair points to independence of the Old Testament description, which argues further for the historicity of the Synoptic portrait of John’. It is indeed hard to see how Mark’s description of ‘camel’s hair’ could have originated in the description of Elijah, though it is a non-sequitur to conclude the detail must therefore be historical. (NV, 117. My bolding)

It is a pity that Rivka Nir’s new work on John the Baptist, The First Christian Believer (link is to Vridar posts on the book), presumably appeared too late (2019) to be included in NV’s study since there we find a strong case for John being a Christian invention. If so, Mark’s use of Scripture, even if only indirectly to explain the Baptist’s diet and clothing, surely has a more extensive theological or “exegetical” function than NV appears willing to easily concede.

In other words, one might say that NV raises many points that potentially open up deeper discussions.

The baptism, the spirit and the voice

While rightfully identifying differences between the Elijah-Elisha narrative and the baptism of Jesus NV at the same time downplays the likelihood that differences can sometimes be similar by a kind of syzygistic reversal or transvaluation:

Elisha and Elijah miraculously cross over the Jordan (2 Kgs 2:8; also 2 Kgs 2:14; cf. Exod. 14:21-22), whereas Jesus is baptized by John in the Jordan (Mk 1:9); Elisha receives Elijah’s spirit (2 Kgs 2:9, 15), whereas Jesus receives a spirit from heaven (Mk 1:10); Elisha addresses Elijah as ‘father’ (2 Kgs 2:12), whereas the voice from heaven addresses Jesus as ‘son’ (Mk 1:11). And the most remarkable detail of 2 Kgs 2:8-12, the ascension of Elijah to heaven in a chariot of fire, has no parallel in Mk 1:4-11. (NV, 120)

If a crossing of the Red Sea can be represented as a baptism by Paul (1 Cor 10:1-2) then can we not see the crossing of the Jordan in the same way? If Elisha receives Elijah’s spirit, is not Jesus depicted as greater than Elisha by receiving God’s spirit? Elisha addresses Elijah as “father”, so don’t we have another mirror replication when the father addresses Jesus as “son”? If there is an ascent to heaven in a fiery chariot, is there not a contrasting reversal with a descent of the dove on Jesus? But given that the author of the Gospel did not mention Elisha at all, NV would argue (as he does in another section) that it is difficult to conclude that Elisha was feeding our author’s imagination.

Overall, NV’s discussion is careful and thorough and his cautious conclusions encourage the serious reader to acknowledge the questions and limitations that must necessarily impinge on any interpretation of the relationship between Elijah and John the Baptist. Sometimes, though, I think he is overly cautious, as when he writes:

For Mark, John the Baptist has influenced the depiction of Elijah as much as, if not more than, Elijah has influenced the depiction of John. If Elijah precedes the Messiah, it is because John precedes Jesus, and not the other way around. Rather than reflecting contemporary expectation of Elijah as the precursor to the Messiah, the germ of the idea is encountered for the first time in Mk 1:2-11. And it is this idea, as interpreted by Matthew (11:13-14; 17:10-13), that would eventually grow into the later Christian concept of Elijah as the messianic forerunner, first articulated explicitly by Justin Martyr (Dial. 49.1). (NV, 122)

But Justin Martyr is pointing out what Jews believed about Elijah preceding the Messiah. The Jews were hardly likely to copy that idea from the Christians. The Jewish view surely preceded the Christian one so the author of the Gospel of Mark necessarily embraced the idea from the Jewish culture. It must follow that the evidence we have indicates Mark was drawing on Scripture and not history or another narrative idea. I am sure NV is aware of that point since later in the same chapter in a footnote he cites the same passage by Justin Martyr as part of the Jewish evidence for his claim that

Both prophets [i.e. Elijah and Moses] were expected to return in the last days 275 . . .

275. Elijah: Mal. 4:5; Sir. 48:10; 4Q521 2:3?; 4Q588 1:2?; Sib. Or. 2:187-189, 194-202; Apoc. El. 4:7; 5:32; Justin, Dial. 8:4; 49:1; m. Eduy. 8:7; m. Sot. 9:15; b. Erub. 43a-b; . . . (NV, 193)

Readers who have been following this series will be aware of NV’s use of Bruce Fisk’s classification of primary and secondary Scripture: primary referring to the passage that the new story is centred on and secondary referring to other texts drawn from different contexts to enrich the narrative details. One of the more difficult secondary Scriptures to identify in the baptism scene is the voice from heaven declaring,

“You are my beloved son in whom I am well pleased.”

The scholarly commentaries and articles on this passage are legion and NV takes us through many of the possibilities with references to Isaiah 42:1, Psalm 2:7 and Genesis 22:2 – among other verses – as well as some of the early interpretations of the gospel passage. If one has been persuaded by Jon D. Levenson’s The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son (link again is to the archive of the posts discussing this hypothesis) I think one is going to hang on to the view that Mark presented Jesus as akin to another Isaac but for many more reasons than that one heavenly pronouncement.

The introduction of the Gospel of Mark is indeed rich in allusions to and quotations of Scripture and they are presented both explicitly and subtly.

Whilst these three passages [in Mark 1:2-11] do not exhaust all potential scriptural references in the prologue (i.e. 2 Kgs 2:8-12; 5:9-14; Pss. 18:9; 144:5; Gen. 22:2), they account for 44 of the 175 words in Mk 1:2-11, so at least one quarter of the opening narrative depends on the language of the Jewish scriptures. Though scholars have a tendency to see a far greater hermeneutical significance in these three passages than is perhaps there, the prologue shows that scriptural language is an indispensable feature of Mark’s writing, whether or not the reader is supposed to identify the source. (NV, 125)

NV focuses on discrete references as found in each verse or pericope. From this perspective, yes, I think it can be argued that it is far too easy to “over-interpret” the use of Scripture in the gospel. I mentioned Levenson’s hypothesis. His hypothesis builds on far more than singling out some “proof-texts” to make his case. What I am saying is that a significant value of NV’s work is that it serves as a warning against being too quick to argue by “proof-texting” alone.

The wilderness and its sequel

It is easy to latch on to one possible source from Scripture (e.g. Israel trekking forty years in the wilderness as the inspiration for Jesus’ forty-day sojourn in the wilderness) and another value of NV’s study is his references to many other possible sources, including sources from Jewish traditions and pseudepigrapha (e.g. Abraham in the Testament of Abraham meeting an angel who supplies him with spiritual bread and water on their journey to Horeb in the wilderness; Elijah, while in the wilderness, explicitly warned that he would be “tested” in pseudo-Philo’s LAB). NV’s discussion of the role of Satan in the Gospel of Mark‘s “testing” of Jesus treats Satan as an opponent of God as he is in much of the literature of the day, but Satan sometimes appeared as a “testing” servant of God, too, who was acting according to God’s will. I wondered if consideration of this less adversarial role of Satan would have enriched NV’s discussion with more options for Satan’s place in both the Gospel of Mark and its possible antecedents.

While NV rightfully urges against being too quick to read a particular significance into the use of a Scripture, sometimes he seems to rely on little more than subjective opinion rather than analytical challenges to ideas he opposes. For example, NV acknowledges that Adam Winn has soundly established that Mark has based several episodes on the Elijah-Elisha model but when a comparison advanced by Winn is not as strong as others, NV responds:

There is, however, no clear sign 1 Kings 19 has influenced the proclamation of the kingdom in Mk 1:14-15. Favouring the allusion, Adam Winn has argued that 1 Kgs 19:15-18 and Mk 1:14-15 reflect ‘parallel proclamations about the kingdom of God’ – in the sense that Elijah’s task of anointing Hazael, Jehu and Elisha and Jesus’ announcement that the ‘kingdom of God has come near’ . . . both concern the establishment of divine rule over human affairs. To this, one can add other loose similarities: Elijah is tasked with anointing kings . . . whilst Jesus announces the kingdom . . . of God and is himself anointed (1:9-11); Elijah receives a revelation at Horeb . . . whilst Jesus’ proclamation of ‘good news of God’ . . . implies a revelation from God; Elijah retreats into the wilderness following the violent threats of Jezebel . . . whilst Jesus emerges from the wilderness following the arrest of John . . . . As Mk 1:14-15 and 1 Kgs 19:15-18 both fall between their respective ‘wilderness’ and ‘call’ narratives, it is tempting to see them as equivalent episodes despite their obvious differences. But the more natural conclusion is that Mark has simply deviated from the scriptural model. Other scripturalized narratives similarly deviate from their model. For example, in the episode of Abram in the fiery furnace (LAB 6) . . . . Mark 1:12-20 features a similar sort of scripturalized intercalation, with the scripturalized narratives of Jesus in the wilderness (1:12-13) and the call of the disciples (1:16-20) placed either side of Jesus’ inaugural proclamation of the kingdom in Galilee, a pivotal moment which acts as the fulfilment of the words of John in 1:7-8, and indeed the αρχή τοῦ εύαγγελίου of 1:1. (NV, 133f)

In my opinion, the existence of a series of strong parallels between texts would naturally favour interpreting “weaker” parallels in the same context as also being deliberate imitations. Furthermore, if a new narrative at a certain point detours from the one on which it is based, one would presume the author has a sound literary and thematic reason for the detour. In the above example, I would have preferred a more detailed engagement with the larger argument of Winn to demonstrate that the author has “simply deviated from the scriptural model”. On the other hand, perhaps I am one of those whom NV is attempting to “loosen up” and to become more critical of long-held interpretations.

No doubt many have read Jesus’ call of his first disciples in the light of Elijah’s call of Elisha and concluded that Mark was consciously portraying the superiority of the former in that Peter, Andrew, James and John immediately drop all, leave parents without so much as a good-bye, and follow Jesus, while in the latter case Elisha begs to return to have a farewell meal with his family. Interestingly, though, NV points out that Josephus (Ant 8.13.7) and other rabbinic tradition likewise spoke of Elisha “immediately” following Elijah. Perhaps Jewish interpreters were also embarrassed that Elisha paused a few hours before following his master.

Before concluding this section of his discussion NV speculates again on the historicity behind the narrative:

That Jesus gathered his own disciples appears to have been a widely known tradition (1 Cor. 15:5; Rev. 21:14) and it may have been this fact alone that led the author of Mk 1:12-20 to compose a scripturalized narrative in which Jesus calls his disciples in the manner of Elijah . . . (NV, 137f)

Such speculation fails to address why Mark would choose to liken Jesus’ attracting disciples to the manner of Elijah’s calling Elisha. Recalling Occam, there is no logical need to introduce a hypothesis that Mark was attempting to explain a historical situation when the only evidence we have for the narrative is that he was inventing a story based on an identifiable source in Scripture. To repeat NV’s own words that I quoted at the beginning,

. . . . it is a non-sequitur to conclude the detail must therefore be historical. (NV, 117)

NV discusses more details than I have addressed here, of course, and within the contexts of antecedent languages and manuscripts and traditions. I’ll cover a few more in coming posts.

Vette, Nathanael. Writing With Scripture: Scripturalized Narrative in the Gospel of Mark. London ; New York: T&T Clark, 2022.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

For what it’s worth, maybe nothing, I read a book by Craig Evans on the Essenes and Dead Sea Scrolls, where he mentioned Isaiah 40:3 “The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, Make straight in the desert a highway for our God”…

He used that as a reason that perhaps the Qumran’s location was chosen, in the desert, at the base of a gorge (highway) to the Dead Sea, that would be made straight, and a paradise at the coming of the Lord.

Assuming Mark was written well after 73AD, when Qumran and the Essenes were destroyed by the Romans, Mark wouldn’t want to quote Isiah exactly, leaving out “Make straight in the desert a highway”, especially when connecting John the Baptist to Jesus, because Mark might not have wanted to associate directly Qumran/Essenes with John and Jesus. Trying to disassociate the failed Essenes movement from Jesus, maybe? By 73 AD, I expect it was we’ll known that the Essenes highway for the Lord was a failure.

Analogy: Kind of like the today’s educated baby boomers (like Mark) disassociating themselves from the 70’s Hippy Movement 🙂

“A Portrait Of Jesus’ World – The Essenes And The Dead Sea Scrolls | From Jesus To Christ – The First Christians | FRONTLINE | PBS”. http://www.pbs.org.

Some still believe in the magical Essenes at Qumran? I thought that had all been debunked by the archaeology.

Hi Mark.

I’m afraid I don’t understand your comment. Are you saying that there weren’t Essenes at Qumran, or that there were but they weren’t magical? There does seem to be a problem with defining Essenes since Josephus has his own take on the subject.

https://vridar.org/2022/08/06/some-underlying-tradition-a-review-of-writing-with-scripture-part-10/#comment-232324

The French priest Eduard-Marie Gallez doesn’t believe in Qumran being much more than a plantation for growing Balsam like Ein Gedi to the south and some places around Jericho to the north also were.

Though he may be a bit of a Latin Mass fringe figure and a fellow traveler of certain alt-right currents in France I read his stuff not for that but for the Ebionite/Nazarene insights into Islamic Christology. Trying to pin down which Jewish Christian sect on its own of in combination with others it absorbed morphed into what we now know as Islam the 3rd big branch of Abrahamic Religion.

When you report that “NV guides the reader through both the Greek and Hebrew versions of the Scriptures in order to … identify the one being prophesied: Elijah or the Messiah?”, surely he is setting up a blatant false dichotomy?

For one thing, Messiah is not Markan vocabulary, unless one translates ὁ Χριστός as “Messiah”. For another, YHWH, aka the Lord in the LXX, should be one of the options for the one who is about to come according to the scriptures, or “Jesus from Nazareth” according to Mark. From the way you explain NV’s work, he is perhaps too focused on “scripture” to see how Mark is actually telling his story.

“Elijah or the Messiah” was my shorthand for what I understood of NV’s detailed discussion. I meant by “messiah” Jesus (however he is understood — even if one thinks of the angel who led Israel in the wilderness per Exodus or “the Lord” to come in the last days per Malachi or some other).