In Revelation 12 the character of the narrator-visionary, John, is exposed to two visions in heaven: one of a woman clothed with the sun, moon and the twelve constellations who is about to give birth to a child; the other of a dragon, a war in heaven (against the one clothed in the heavenly bodies of the sun, moon and constellations?) and the fall of that dragon to earth.

Once the dragon has fallen to earth, we learn that the heavenly events were harbingers of events on earth: the woman in heaven is now seen on earth. The moment she gives birth the child is snatched away from the threatening dragon and taken to heaven. (Recall the book of Daniel: there we read that everything that happens on earth is anticipated in heaven; all earthly battles are first fought out in the skies by the heavenly representatives of the earthly powers.) The dragon then chases after the woman who has to flee into the wilderness for safety. The dragon accordingly changes its plans and turns back to attack the other children of the woman. These are said to keep the commandments of God and hold the testimony of Jesus.

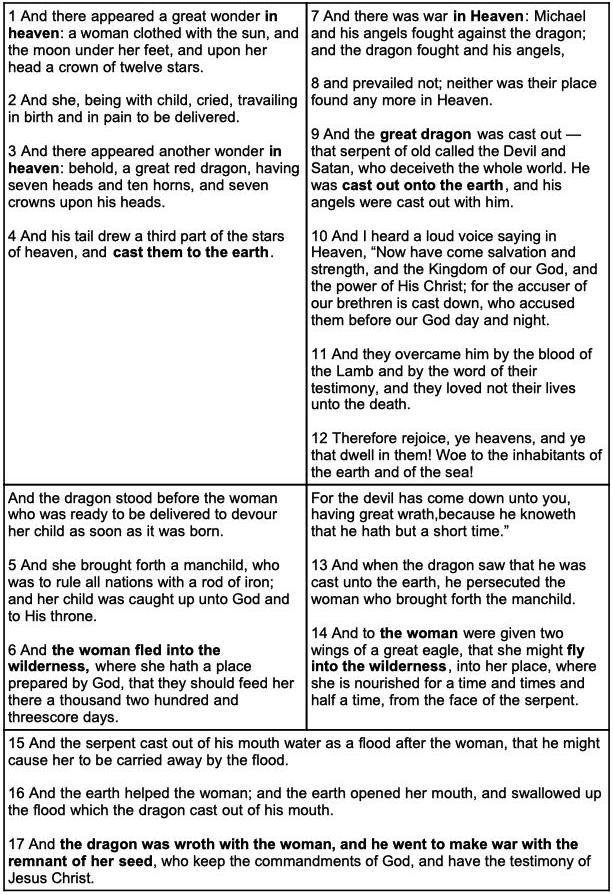

Julius Wellhausen demonstrated the parallel visions in Revelation 12 with the following table:

The following argument is a paraphrase of Wellhausen’s Zur apokalyptischen Literatur.

On earth, the dragon is evidently the Roman empire. (This conclusion derives from a comparison with the information about the beast with seven heads and ten horns in chapters 13 and 17.) The woman appears to be Zion, the twelve-tribes of Israel, who gives birth to the messiah, the one whom Revelation declares will rule the nations with a “rod of iron”. But what kind of Messiah is this? Wellhausen writes,

But it is disputed whether Sion and the Messiah are Christian or Jewish terms here. The question is not already answered by the fact that the Revelation of John as a whole, in its present form, is a Christian book. For the last author used sources and possibly Jewish sources. (Wellhausen, 218 – translation)

The episode of the birth and immediate rapture of the child from earth is unlike any Jewish expectation of a messiah that we know of, but it is also clearly not a part of all we know of Christian views of the messiah, either.

Revelation 12 can hardly be interpreted in any way that allows for a growth of the child to manhood, his life and ministry on earth, nor of his death on earth. Revelation 12 clearly leads readers to understand that the child is snatched up to heaven the moment it is born. Note that in verse 4 the dragon is standing beside the woman waiting for the moment the child is born. There is no scope for the child to grow to adulthood on earth.

Many Christians have interpreted the woman of Revelation 12 as the church. But that view likewise brings insuperable difficulties with it. How can the messiah be the son of the church, one born through the church? The Christian church holds the Christ to be its head, not its child.

If we think of the woman as Israel, however, there is no problem with the idea of the messiah being born from that nation represented as a woman. Jesus was born of his mother Israel or more specifically, Judah.

Another difficulty with reading Revelation 12 as an orthodox Christian text is that it claims the primary enemy of the messiah is the Roman empire. Not the Jews, or any group among the Jews such as the Pharisees or Herodians. In Revelation 12 the only enemy of the messiah is Rome. The Jews are the (loving) mother of the messiah. But Rome is not depicted as the enemy of the messiah from the moment of his birth but even before his birth! How do we make sense of this from a Christian perspective?

Revelation 12 allows no room for a crucifixion of the messiah, certainly not on earth. The Jews are not enemies of the messiah in Revelation 12. Only the Romans are his enemy.

From all of this it follows that the flight of the woman into the wilderness cannot be an allusion to the flight of Christians from Jerusalem to Pella to escape the final destruction of Rome in 70 CE, nor can that flight of the woman in Revelation 12 be a reference to any part of the body of Christianity at any time. The flight to Pella of the Jewish Christians is said to have happened some near 70 years after the birth of the messiah. That time gap is not possible for Revelation 12’s account of the birth of the child and flight of the woman. The two are effectively simultaneous events.

Wellhausen concludes,

The child is not the historical Messiah of the Christians, but an imagined one of the Jews. The vision consists of a Jewish prophecy. (220 – translation)

The author of Revelation 12 is drawing upon the time schedule of the book of Daniel to come to 1260 days. In Daniel we read of a persecution by Antiochus Epiphanes and the visionary of Revelation is expecting a similar time-table with the Roman oppressors.

The woman of Revelation 12 is the portion of the Jewish nation that escaped from the Roman army and continued to maintain their polity elsewhere. These were the Jews who fled from Jerusalem and thus escaped a deadly encounter with Roman forces. These Jews — many Pharisees and scribes opposed by the zealots — became the seed of a future Jewish cultural-religious (rabbinical) revival.

The Romans lost interest in pursuing those Jews and turned against those who remained in Jerusalem.

We know from the later chapters of Revelation that the messiah will come from heaven to crush the forces of evil and rule over all nations.

So why has the author of this chapter described the earthly birth of Jesus at all? What was the point?

Wellhausen finds the answer to that question given by Eberhard Vischer :

Vischer already answered this aptly. There seems to be a compromise between two equal demands. On the one hand, according to the old conception, the Messiah must come forth from the people of Israel, on the other hand, according to Daniel, from heaven. This is rhymed by the assumption that he was born of the mother Sion shortly before the beginning of the three and a half years, but that he was caught up into heaven immediately after his birth and thus did not stay on earth during the time of need. (Wellhausen, 221 – translation)

An analogy can be found in Isaiah chapters 7 to 9: Immanuel (“God with us”) is born at the beginning of a critical time, then disappears from view for a while, and suddenly appears in full glory at the end. That’s Wellhausen’s comment, but he adds that obviously in Isaiah there is no contrast between heaven and earth as abodes for the Christ but that Isaiah does present the pattern of birth, disappearance and return at maturity at the moment of the final stage of the crisis.

So what does all of this have to do with the new series I have begun about Revelation 11 and the command to measure the temple?

Go and measure the temple

The author clearly expected the inner sanctuary of the temple to escape the wrath of Roman forces. Roman soldiers would overrun the city and even the outer court of the temple. But there they would be held back.

That scenario flatly contradicts what we read of in the canonical gospels where Jesus prophesied that the temple must necessarily be destroyed stone by stone. In Revelation we read that the temple proper will not be trodden underfoot by gentiles; in the gospels we read the opposite. How could a Christian a generation after the death of Jesus possibly flatly contradict what he surely must have known what Jesus had prophesied about the temple?

The problem is magnified by Wellhausen’s observation that in Revelation 12 we read that the remnant who survive are those who flee to the wilderness, yet in Revelation 11 it is those who remain within the Jerusalem temple who are saved!

Revelation 11:1-2 appears to depict Jews who do much more than merely occasionally attend the temple for worship. No, Revelation 11:1-2 is speaking of Jews who have made their residence there. How can we fail to be reminded of what Josephus has informed us of the Zealots who made their headquarters in the temple during the Roman war of 66-70 CE!

Wellhausen therefore interprets the hope expressed in Revelation 11:1-2 as derived from the Zealots who held fast to the defence of Jerusalem and especially its temple, and the expectation of Revelation 12 as coming from the circle of those who opposed the Zealots, such as many of the Pharisees.

One group determined to fight to the death to defend their ways; the other determined to leave the fighting to God and concentrate on merely obeying his commands. One party was primarily political, the other primarily religious — to use our modern terminology.

To translate the words of Wellhausen,

These two prophecies document the opposition of the Jewish parties during the Roman war. They both presuppose that things have gone wrong so far, they both hold on to hope, but from the point of view of the camp to which they belong. (Wellhausen, 223)

(Since this post is to be included in my series on Thomas Witulski’s case for a setting of Revelation to the Bar Kokhba war of 132-135, I need to put in a reminder here that Wellhausen’s time-frame will be subject to revisionist arguments in future posts.)

And have the testimony of Jesus

There can be no doubt that the last words in the final verse (17) of Revelation 12 are written by a Christian:

And the dragon was wroth with the woman, and he went to make war with the remnant of her seed, who keep the commandments of God, and have the testimony of Jesus Christ.

Wellhausen acknowledges this obvious fact. But since those final words, “have the testimony of Jesus”, are found at the end of a passage in which all that we know of Christian teaching is contradicted, we must explore further to understand what is going on here.

Wellhausen further notes that the whole of verse 11 can likewise be recognized as a Christian addition:

And they overcame him by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their testimony, and they loved not their lives unto the death.

That verse does not logically follow or fit in with the previous verse. Verse 10 proclaims that the dragon/serpent/devil is overcome by Michael and cast down to the earth and verse 12 calls on the inhabitants of heaven to rejoice in this victory. That the saints overcome the same enemy by the blood of the Lamb is an intrusion into the flow of the thought of the larger passage:

10 And I heard a loud voice saying in Heaven, “Now have come salvation and strength, and the Kingdom of our God, and the power of His Christ; for the accuser of our brethren is cast down, who accused them before our God day and night.

11 And they overcame him by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their testimony, and they loved not their lives unto the death.

12 Therefore rejoice, ye heavens, and ye that dwell in them! Woe to the inhabitants of the earth and of the sea! For the devil has come down unto you, having great wrath, because he knoweth that he hath but a short time.”

Look back at the passages we have covered. You no doubt had niggling doubts or questions in the back of your mind about some of the interpretations expressed.

In Revelation 12 we first read of a woman in heaven who is about to give birth. But then without explanation we find the woman on earth. The author gives the reader no account of how the move was made from heaven to earth. The leap in the setting causes some confusion that requires the reader to make quick mental recalculations to follow the story.

Now I do not have expertise in ancient languages so I can only present the argument set forth by Wellhausen — as I have been doing up to now anyway. The reasoning set out is that the Jewish source behind Revelation 12 was originally composed in Hebrew or Aramaic. Wellhausen notes that certain words in 11:1-2 and the whole of chapter 12 can easily be retroverted into a Hebrew or Aramaic idiom or expression.

In Revelation 11:1-2 the Greek phrases singled out as candidates for straightforward Hebrew or Aramaic retroversion are:

ἐδόθη μοι κάλαμος = was given to me a measuring rod

Ἔγειρε καὶ μέτρησον = Rise, and measure

ἔκβαλε ἔξω = leave out

As for the twelfth chapter, Wellhausen remarks,

No less in ch. 12. The whole chapter can be retroverted with ease; everywhere . . . Hebrew idiom is encountered. The most important examples are given in v. 6 compared with v. 14: ὅπου ἔχει [where there] v. 6. 14, ἵνα ἐκεῖ [so that there] v. 6 = ὅπου ἔχει [where she has] ν. 14, τρέφουσιν [they should nourish] ν. 6 = τρέφεται [she is nourished] ν. 14). More distant syntactic Hebraisms are ὤφθη καὶ ἰδοὺ [was seen and behold] ν. 3 and the infinitive πολεμῆσαι [warred] ν. 7 (Ewald § 351 c). Lexical: υἱὸς ἄρσεν [a son male] ν. 5, οὐκ ἴσχυσεν [not had the strength] ν. 8, οὐδὲ τόπος εὑρέθη αὐτῶν [nor a place was found for them] ν. 82). If only one could also assume, conversely, that the Christian passages were written in Greek throughout! But this assumption, alas, cannot be corroborated, and so the means of distinction fails. Only this can be said, that original Greek passages are hardly of Jewish origin.

2) αἱ δύο πτέρυγες τοῦ ἀετοῦ [the two wings of the eagle] is probably כנפים כנשר

(Wellhausen, 224 – translation)

In the table at the opening of this post we see that verses 1 to 6 are a variant of verses 7 to 14. The two passages only erupt with difficulties when read as a narrative sequence. No, the first six verses are not a natural introduction to the following verses. Nor are verses 7 to 14 a natural sequel to verses 1 to 6. The two sections are not presented in Revelation 12 in their original complete forms. We have already commented on the disjunction of the woman in heaven and the woman on the earth – no explanation appears to help us make sense of this leap. Take another look at the tabular format of Revelation 12 at the beginning of this post and we see that again in verse 13 there is no introductory explanation for the presence of the woman who is attacked.

The author of Revelation has taken Jewish texts and attempted to combine them to include the persecution of the woman on earth.

Wellhausen asks us to consider whether Revelation 12 is best understood as an attempt by a Christian to create a narrative from Jewish sources with a few Christian additions — all this in the process of creating the new narrative that we read in this twelfth chapter of the apocalypse. Wellhausen does not ask the question, but I do: Have Jewish writings related to the Bar Kohba war of 132-135/6 been adapted to fit with a Christian apocalypse?

If so (and here I am injecting my own thoughts) can we possibly imagine a Christianity that was even as late as the time of Hadrian in its pre-natal state? Were the canonical gospels — and even the letters attributed to “Paul” — still unknown quantities as late as the 130s CE.? We are accustomed to thinking of the war of 66-73 CE being the critical turning point. What if answers are more cogent if we refer instead to the Bar Kochba war of 132-136? I don’t mean to imply that that was Wellhausen’s view. But it is one that keeps coming back to my mind.

Wellhausen, Julius. “Zur apokalyptischen Literatur.” In Skizzen und Vorarbeiten, 215–49. Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1884. http://archive.org/details/skizzenundvorarb06well.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“Wellhausen therefore interprets the hope expressed in Revelation 11:1-2 as derived from the Zealots who held fast to the defence of Jerusalem and especially its temple, and the expectation of Revelation 12 as coming from the circle of those who opposed the Zealots, such as many of the Pharisees.

One group determined to fight to the death to defend their ways; the other determined to leave the fighting to God and concentrate on merely obeying his commands. One party was primarily political, the other primarily religious — to use our modern terminology.”

I wonder if he was influenced by his Documentary Hypothesis methodology. If he thinks Revelation is an edited, pieced together text from two sources, one political, one religious. Like D and P. Seems unlikely this could happen in Revelation, as happened in the Pentateuch. Maybe wishful thinking on his part.