Key points in this post:

- Both Nero and Hadrian waged war with the Jews.

- Both Nero and Hadrian had a special devotion to enriching and reviving the culture of the Greek world

- Nero pursued the cultic-religious worship of his own person, Hadrian that of Antinous (and more to be covered in upcoming posts)

- The travel coins minted by Hadrian mirror the Corinthian local coinage reflecting Nero’s visit there.

- The rule of Hadrian witnessed a flourishing of Jewish apocalyptic writings, including the identification of Hadrian with Nero redivivus.

–o–

But there is little agreement on exactly how Revelation fits with the history of the Roman empire. Kreitzer lists four scenarios to demonstrate those difficulties:

Rev 11:8 The beast, which you saw, once was, now is not, and yet will come up out of the Abyss and go to its destruction. The inhabitants of the earth whose names have not been written in the book of life from the creation of the world will be astonished when they see the beast, because it once was, now is not, and yet will come.

9 “This calls for a mind with wisdom. The seven heads are seven hills on which the woman sits. 10 They are also seven kings. Five have fallen, one is, the other has not yet come; but when he does come, he must remain for only a little while. 11 The beast who once was, and now is not, is an eighth king. He belongs to the seven and is going to his destruction.

Scenario one:

- The five fallen emperors are Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, Vespasian

- The “one who is” (at time of writing), Titus

- Domitian is the one “to appear” (foreseen by the author) as Nero redivivus.

Scenario two (omitting those who reigned for very short times):

- The five fallen emperors are Caligula, Claudius, Nero, Vespasian, Titus.

- The “one who is”, Domitian

- The seventh and eighth are yet to come

Scenario three:

- The five fallen emperors are the Julio-Claudians (Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero)

- The “one who is” is then Galba

- The one to come and to reign but a short time is then Otho — to be followed by Nero’s return

Scenario four is proposed by the same person who actually proposed scenario three above:

(The author) was writing in the early second century, a refugee, from a later wave of persecutions, and using the events of 64 to 69 in Rome as a cloak for his views of his own times. … To the author of Revelation the cheap and nasty legend of the risen Nero would seem the perfect legend for the anti-Christ, ever opposed to the truly and gloriously Risen Lord of his own faith. (John Bishop, Nero: The Man and Legend, p. 174)

The Nero myth was itself a variable quantity. It is as Kreitzer observes

The fact that ancient Jewish and Christian authors were able to find new and creative means of applying the Nero redivivus mythology to their own situations is particularly interesting. (1988, 95)

Indeed. And as we shall see, the emperor Hadrian who crushed the second Jewish rebellion led by Bar Kochba was also identified as the “Nero returned”.

Before we take on the details, let’s get some context.

Origin and Development of the Nero Redivivus Myth

We might say that there are three conditions necessary for a belief in someone’s return:

1.) A widespread popular affection for the figure by people who regarded the deceased as their benefactor or defender

2.) A general feeling that the figure concerned died leaving his work incomplete

3.) Mysterious or suspicious circumstances surrounding the figure’s death.

(And we might thank M. P. Charlesworth for helping us out with that list.)

All three conditions apply to Nero. But as time went on and Nero didn’t return the hopes took a new twist: Nero was going to come back from the dead and return! As history and reality faded, myth took their place.

Non-Jews had hoped for Nero’s return. Jews, on the other hand, not so much. The idea of his return was good fodder for end-time prophecies such as those in the Sibylline Oracles, however. The Jewish oracles accordingly turned Nero into an end-time enemy of God.

One set of these oracles (book 5) has been dated between 70 and 132 CE.

The oracles identify Nero by the following descriptions:

- He initiated the war that led to the destruction of Jerusalem

- He murdered his mother Agrippina

- He claimed to be God

- He loved the Greeks and those in the “east” (including Parthia) and they all loved him.

- He cut through the isthmus of Corinth to create a canal joining two seas

Sibylline oracles identified Nero by means of known historical facts about him. And he was depicted there as an evil ruler. So where does Hadrian enter the story?

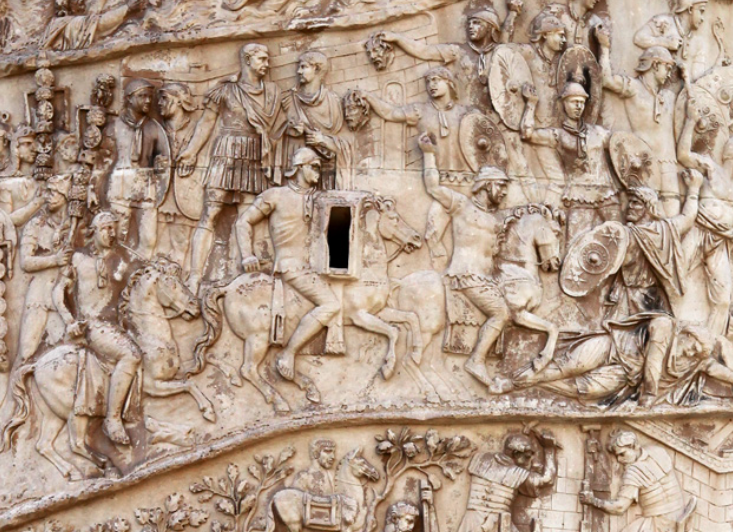

Hadrian as Nero redivivus

Curiously, Hadrian, though presented in a favourable light, is surrounded by descriptions of the unpleasant Nero. Not only is Hadrian nested within portrayals of Nero, but he also shares some of Nero’s historical identifiers. Given that the author here believes Hadrian is on the side of good and Nero on that of evil, we cannot imagine that Hadrian was understood to be Nero redivivus.

But the oracle was fearful. What of the future?

After all, Nero had brought savage punishment upon the Jews; so had the Flavians (Vespasian and Titus) who succeeded him. The oracle laments the existence of all these rulers. Then came the aged Nerva followed by Trajan. The oracle does not totally condemn those rulers: they had not caused trouble. And Hadrian, at least for now, seemed benign enough, but the past record of emperors still cast its shadow of traumatic memories. So the oracle wrote of Hadrian (5:46-50),

After him another will reign,

a silver-headed man. He will have the name of a sea.

He will also be a most excellent man and he will consider everything.

And in your time, most excellent, outstanding, dark-haired one,

and in the days of your descendants, all these days will come to pass.

Hadrian might be a fine man, but when he dies the end-of-time calamity will come — that was the message.

Still, why was Hadrian associated with Nero at all in these oracles?

Larry Kreitzer has an explanation:

It seems clear that Hadrian consciously adopted many of Nero’s benevolent policies toward the Eastern half of the Empire, deliberately modelling himself on his predecessor in this regard.

One of the important secondary sources of evidence for Hadrian’s preoccupation with the Emperor Nero is the numismatic evidence of the Imperial Roman mints. The fact that Hadrian borrowed some of Nero’s coin types for his official imperial mint issues, and used them as a means of popular propaganda, is indisputable. (1989, 69)

I’ll return to the numismatic evidence soon. For now, though, let’s look into K’s first point about Hadrian consciously adopting Nero’s policies: Continue reading “Hadrian as Nero Redivivus”