This post is detailed. But it is getting down to the nitty gritty of a case for the midrashic creation of the Jesus figure in the gospels.

Nanine Charbonnel cites four intriguing instances.

A. I Am/I Am He/I and He … and we are all together

Many of us are familiar with Jesus declaring “I am” (ἐγώ εἰμι) which echoes Yahweh’s self-declaration in the Pentateuch; less familiar are the moments when Jesus says, “I am he” (ἐγώ εἰμι αὐτός – e.g. Luke 24:39), and that sentence echoes the second part of Isaiah (אֲנִי-הוּא = hū ’ănî = I [am] he; LXX = ἐγώ εἰμι = I am) and liturgies of the Jewish people. (I’ll simplify the Hebrew transliteration in this post to “ani hu” (= I he).

These self-identifications bring us back to Exodus 3:14 where God reveals himself to Moses at the burning bush: “I am he who is”, which in the Greek Septuagint is ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ὤν.

But we need to look again at those words [hu ani] in Deutero-Isaiah:

In Isaiah 41:4; 43:10, 13; 46:4; 48:12; 52:6 we read God declaring, I am he [ani hu] (=me him) אֲנִ֣י ה֔וּא

We will see that this expression, “I he” is related to the festival of Tabernacles or Sukkoth.

But first, we note that during New Testament times at the Feast of Tabernacles or Tents worshippers walked around the altar each day singing “O Yahweh save us now, O Yahweh make us prosper now”, which is a line from Psalm 118:25

| נָּא | הַצְלִיחָה | יְהוָה | אָנָּא | נָּא | הוֹשִׁיעָה | יְהוָה, | אָנָּא |

| na | hatzlichah | yhwh | ana | na | hoshiah | yhwh | ana |

| now | prosper us | [we pray / beseech you] | now | save us | [we pray / beseech you] |

Now in rabbinic literature, in Mishnah Sukkah 4:5, we find another version of this liturgical sentence was said to be used during the temple ceremony.

Each day they would circle the altar one time and say: “Lord, please save us. Lord, please grant us success” (Psalms 118:25). Rabbi Yehuda says that they would say: Ani waho, please save us. And on that day, the seventh day of Sukkot, they would circle the altar seven times.

| הוֹשִׁיעָה | וָהוֹ | אֲנִי |

| hoshiah | waho | ani |

| save us | [taken to be a substitute for the divine name by some scholars – see Baumgarten below] | I (Hebrew); (confusingly, ana in Aramaic means “I”. By hearing the original Hebrew ana as the Aramaic ana, the transformation to Hebrew “I” follows.) |

Both ani and waho may be considered “flexible” as I’ll try to explain.

- ani in Hebrew means “I”

- ana in Hebrew means something like “we pray” as above

Aramaic was the relevant common language in New Testament times, however, and it’s here where the fun starts.

- ana in Aramaic means “I”

So we can see how the Hebrew “we pray” can become the Aramaic “I”.

If waho, והו, began as a substitute for the divine name it could when pronounced easily become והוא, wahoû, which is the Aramaic for “me”.

NC writes,

qui peut être une manière de dire ‘ani wahoû’, “moi et lui”.

Translated: which can be a way of saying …. “me and him”. (The “wa” = “and”.)

Not cited by NC but in support of NC here, Joseph Baumgarten in an article for The Jewish Quarterly Review writes,

Mishnah Sukkah 4.5 preserves a vivid description of the willow ceremonies in the Temple during the Sukkot festival. Branches of willows were placed around the altar, the shofar was sounded, and a festive circuit was made every day around the altar. The liturgical refrain accompanying the procession is variously described. One version has it as consisting of the prayer found in Ps 118:25, אנא ה׳ הושיעה נא, אנא ה׳ הצליחה נא , “We beseech you, O Lord, save us! We beseech you, O Lord, prosper us.” A tradition in the name of R. Judah, however, records the opening words as follows: אני והו הושיעה נא. The meaning of this enigmatic formula has occasioned much discussion among both ancient and modern commentators.

In the Palestinian Talmud the first two words in the formula were read אני והוא and were taken to suggest that the salvation of Israel was also the salvation of God.

(Baumgarten, Divine Name and M. Sukkah 4:5 p.1. My highlighting)

The same idea is brought out by NC in her quotation of Jean Massonnet. I translate the key point concerning the “I and he” or “me and him”

This may be a way of closely associating the people with their God on an occasion when the Israelites might surround the altar; it was a great moment of the feast […] In a veiled form, one audaciously asked for salvation for the good of the people and of God, as if God – so to speak – was in distress with his people.

(Massonnet, Aux sources du christianisme…., p. 269, cited by NC, p. 317. My highlighting.)

NC adds, again translating,

we are the emphasing the last sentence. He adds: “the idea that God accompanies his people in distress is […] ancient and widespread”, see Isaiah 63, 9: “in all their distress it is distress for him”. On personal pronouns see Pierre Bonnard, L’Évangile according to Saint Matthew, p. 64, note.

Finally, one point I failed to mention earlier, recall our earlier discussions of the importance of gematria. In that context it is not insignificant that “ana YHWH” has the same numerical value as “ani waho”.

B. Dabar, a Word in Silence

The Hebrew word for “word” can equally mean “act”. I quote references from a couple of old authorities:

דָּבָר dâbâr . . . Strong’s definitions:

a word; by implication, a matter (as spoken of) or thing; adverbially, a cause:—act, advice, affair, answer, any such (thing), . . . .

Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament:

dābār. Word, speaking, speech, thing, anything, …, commandment, matter, act, event, history, account, business, cause, reason,

The dābār is sometimes what is done and sometimes a report of what is done. So, often in Chr, one reads of the acts (dibrê) of a king which are written in a certain book (dibrê). “Now the acts of David the king … are written in the book of Samuel the seer, and in the book of Nathan the prophet, and, in the book of Gad the seer.” In the KJV of II Chr 33:18 acts, words, spake and book are all some form of dābar/dābār. And in the next verse, sayings is added to this list! The Hebrew name for Chronicles is “the book of the words (acts) of the times” (sēper dibrê hayyāmîm). Here “words [ (acts) of the times” is equal to “history” — “annals.”

[In addition, the word of the Lord is personified in such passages as: “The LORD sends his message against Jacob, and it falls on Israel” (Isa 9:8 [H 7]); “He sent his word and healed them” (Ps 107:20); “He sends his command to the earth” (Ps 147:15). Admittedly, because of the figure it appears as if the word of God had a divine existence apart from God, but Gerleman rightly calls into question the almost universal interpretation that sees the word in these passages as a Hypostasis, a kind of mythologizing. Gerleman suggests that this usage is nothing more than the normal tendency to enliven and personify abstractions. Thus human emotions and attributes are also treated as having an independent existence: wickedness, perversity, anxiety, hope, anger, goodness and truth (Ps 85:11f.; 107:42; Job 5:16; 11:14; 19:10) ….]

(TWOT, p. 399. Of course, we are arguing contrary to the thrust of the last paragraph that certain ancients thought could well have thought differently.)

Try reading the prologue to the Gospel of John with this understanding in mind. The evangelist was playing with the Hebrew text of the creation account in Genesis 1. He was toying with the two levels of meaning of dabar, act and speech. In Genesis the first act is the creation of light. In John 1 we read the second creation of light, a new light to be named “Salvation”, but a light that not all have been able to see, a light that is found in the incarnation of the word/act itself.

Compare Sirach 42:15

In the words of the Lord are his works.

Understood as an act, the word can even be silence, since silence is also an act. Ignatius wrote to the Magnesians, 8:2

. . . there is one God who manifested himself through Jesus Christ, his Son, who is his eternal Word, who came not forth from Silence

(though some manuscripts omit “not”)

NC draws upon Roland Tournaire (L’intuition existentielle. Parménide, Isaïe et le midrash protochrétien) who interprets the word, speech, dabar, as existing beyond time, in eternity rather than temporally, and here existing as the Son in the understanding of our biblical authors John and Paul. Jesus, Tournaire says, brings to light, into appearance for us, this reality of the word, of Yahweh, who himself never leaves the silence of eternity. Translating,

This is the first idea of the proto-christian midrash: the Son does not manifest himself by his word, but by the interpretation that humans imagine to make him speak: parables and speeches are a language adapted to the earthly situation of adam-YHWH. They resonate in human ears because it was designed by human intelligence. . . .

We are there at the heart of the proto-Christian doctrine readable in John and in the most archaic passages of the so-called Pauline epistles. What prevails, in such a doctrine, are not the sayings of the teaching, but the fulfillment by the elevation of the existential idea, which Jesus (‘adam and YHWH) manifests thanks to the certainties of the midrash.

(NC, 318, citing Tournaire, pp. 254-255)

What I am reminded of here is the curious way some of the evangelists play with silence at critical moments in the narrative of Jesus. Silence is a significant motif found also in the book of Revelation and in a number of “gnostic” texts. There is the silence before Pilate that is broken by his declaration of “I am”. Wrede identified the silences in the Gospel of Mark as relating to “the messianic secret”. Is there more to be said about them, though? The Gospel of John is usually understood to be a polar opposite of the Gospel of Mark in so many respects, but I have sometimes wondered if there is rather an underlying unity of the two gospels hidden beneath parables. In Mark we read that Jesus always spoke in a parable and also that he avoided declaring his identity in public; in John we read of Jesus always speaking in parables (though often the parables are only recognized as such by the reader and not the other characters in the narrative) and declaring his identity in public. Yet in both, Jesus remains hidden. Parables and silence both hide his true identity. The effect of the parables in John is the same as the effect of the silence in Mark.

Further, in the Gospel of Mark, we read that the teachings of Jesus are astonishing but we are not told what they are. Only that people are astonished. And he speaks in parables to hide his meaning from the public. In John the Word incarnate is equally hidden but through different narrative techniques. In both we read about a “great teacher” or the Word himself without a teaching except about himself and his identity. (Later, Matthew and Luke, not quite getting this point, flesh out his life with teachings to imitate or surpass the teachings of Moses.)

Does the point made by Roland Tournaire and NC explain why Jesus comes to speak in a way that cannot be understood, to speak in a way that hides his true identity except to those to whom he reveals himself? I suspect so. It makes sense, also, of the play with the motif of silence in the Gospel of Mark and, perhaps, in extra-canonical texts.

(And one more query: is there any relation of this concept to Jesus choosing to write on the ground rather than speak in John 8?)

C. Good News and Flesh — the same Hebrew root

Up to this point I have understood NC to have spoken of a common Greek root behind the words for tent or tabernacle and for body, but my understanding is that the word for tent (skenos) is used metaphorically for the body. I might have misunderstood NC, writing in French, or maybe there is something about the Greek that I am not aware of. But the point is that the same word can equally mean either tent or body. Of equal interest, surely, is that the Hebrew root BSR can be read as either “flesh” or “good news” or “good word”.

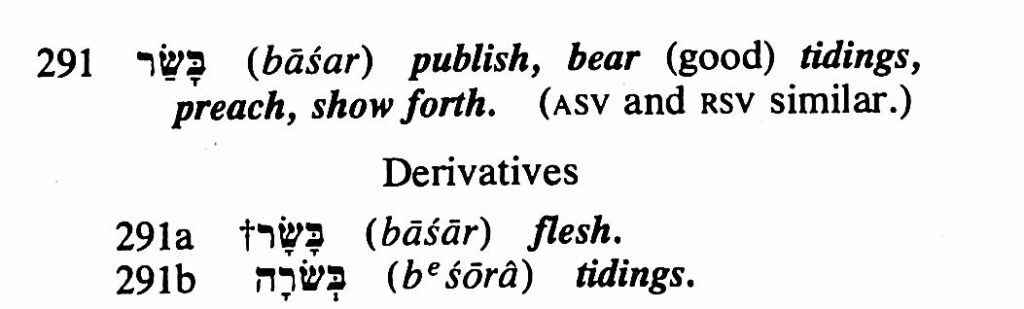

Again I will drag out my Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament:

This root and its derivative occur thirty times in the OT. Sixteen of these are in Samuel-Kings and seven are in Isaiah. The root is a common one in Semitic, being found in Akkadian, Arabic, Ugaritic, Ethiopic, etc. The root meaning is “to bring news, especially pertaining to military encounters.” Normally this is good news . . .

In the historical literature, the occurrences of bāśar cluster around two events: the death of Saul (I Sam 31:9; II Sam 1:20; 4:10), and the defeat and death of Absalom (II Sam 18:19f.) Although David received them differently, both were felt by the messenger to be good news.

This concept of the messenger fresh from the field of battle is at the heart of the more theologically pregnant usages in Isaiah and the Psalms. Here it is the Lord who is victorious over his enemies. By virtue of this success, he now comes to deliver the captives (Ps 68:11 [H 12]; Isa 61:1). The watchman waits eagerly for the messenger (Isa 52:7; cf. II Sam 18:25f.) who will bring this good news. At first, only Zion knows the truth (Isa [40:9; 41:27), but eventually all nations will tell the story (Isa 60:6). The reality of this concept is only finally met in Christ (Lk 4:16-21; I Cor 15:54-56; Col 1:5, 6; 2:13-15).

bāśar. Flesh (rarely skin, kin, body) . . . This word occurs 273 times in the OT. One hundred fifty-three of these are found in the Pentateuch. . . . In Hebrew the word refers basically to animal musculature, but by extension it can mean the human body, blood relations, mankind, living things, life itself and created life as opposed to divine life.

bāśār occurs with its basic meaning very frequently, especially in the Pentateuch, in literature concerning sacrificial practices (e.g. Lev 7:17) . . . The common paralleling with … “bone” to convey the idea of “body” denotes the central meaning of the word dearly (cf. Job 2:5, etc.).

But bāśār can be extended to mean “body” even without any reference to bones (Num 8:7; II Kgs 4:34; Eccl 2:3, etc.). As such it refers simply .to the external form of a person. . . .

If “body” can refer to man, it can also refer to mankind (Isa 66:16, 24, etc.) and even further to all living tilings (Gen 6:19, etc.). . . .

(TWOT, 291-92)

In Isaiah 61:1 we read of the good news of the coming messiah:

The Spirit of the Lord GOD is upon me, Because the LORD anointed me To bring good news lə·ḇaś·śêr לְבַשֵּׂ֣ר

Similarly in Isaiah 41:27

And to Jerusalem, ‘I will give a messenger of good news.’ mə·ḇaś·śêr מְבַשֵּׂ֥ר

Again in Isaiah 52:7

How delightful on the mountains Are the feet of one who brings good news mə·ḇaś·śêr מְבַשֵּׂ֗ר

Nahum 1:15

Behold, on the mountains, the feet of him who brings good news [mə·ḇaś·śêr מְבַשֵּׂר֙], Who announces peace!

Maurice Mergui, whose work (Paul À Patras) NC uses in presenting this point, wants us to notice that it is the spirit that is behind this announcement (Isa. 61:1) of the coming “word”, and that in this messianic promise we can see how close we are to the word, the davar (dabar), becoming flesh in its fulfilment. Paul sees significance in Paul’s frequent contrast between flesh and spirit, admonishing his Corinthians that they are too “flesh” (like rebellious Israelites who complained over being fed the same flesh all the time) and need to be more of the “spirit”.

D. Even mathematics proves the Word was God

The Gospel of John displays many marks of interest in playing with numbers. A source not found in NC’s book but a must-read for anyone interested in some of the detail is Numerical Literary Techniques in John: The Fourth Evangelist’s Use of Numbers of Words and Syllables by M. J. J. Menken. Several shorter works have focussed on the significance of the catch of 153 fish in chapter 21. As for the matching of the sacred name YHWH with the dabar (=word) — both total 26. We may assume that there would be Jewish exegetes of the day who understood that such a match had real significance. The author of the Gospel of John could say he had “proof” that the Word was God.

For details of the 26 link see

- Sentiers, Garrigues et. “Déchiffrons les lettres hébraïques…” GARRIGUES ET SENTIERS. Accessed April 14, 2021. http://www.garriguesetsentiers.org/article-3396135.html.

- ———. “Qui et l’Agneau de Dieu incarné.” GARRIGUES ET SENTIERS. Accessed April 14, 2021. http://www.garriguesetsentiers.org/article-4161983.html.

Both are part of NC’s discussion.

NC concludes this portion of her work by reminding us of what we are reading in the gospels:

1st meaning: the oracle is fulfilled in the storytime; there we find God’s promises fulfilled;

2nd meaning: but it is by the midrashic character of that narrative that we find that fulfilment of the spirit of promise;

3rd meaning: the story is about a figure who is the Name of God personified;

4th meaning: that character has been constructed with the word and with a name that means “YHWH saves”, and whose name by gematria (numerical value) is equivalent to the sacred name represented by the unpronounceable Tetragrammaton.

The last three posts have examined the words behind the Word becoming flesh and their Jewish contexts. Next up is a similar in-depth study of how that Name became flesh.

Charbonnel, Nanine. Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier. Paris: Berg International éditeurs, 2017.

Mergui, Maurice. Paul À Patras: Une Approche Midrashique Du Paulinisme. Objectif Transmission, 2015.

Harris, R. Laird, Gleason L. Archer, and Bruce K. Waltke, eds. Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. Vol. 1. Chicago: Moody Press, c1980. 2 v. ; 26 cm, 1980.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!