Continuing the series Charbonnel: Jesus Christ sublime figure de papier . . .

Continuing the series Charbonnel: Jesus Christ sublime figure de papier . . .

A Messiah to combine the different messianic visions

Nanine Charbonnel [NC] has been exploring various ways the Jesus figure of the gospels was drawn to embody certain groups of people and now proceeds to discuss the way our evangelists (gospel authors) also found ways to encapsulate the different Jewish ideas about the Messiah into him as well. I have posted many times on Second Temple messianic ideas and questioned a common view that there was “a rash of messianic hopes” in first-century Palestine. I post links to some of these posts that illustrate or expand on NC’s points.

Various Messiahs

Vridar posts on Second Temple Messiahs

Here are some tags linking to the posts. (As you can see, there is some overlap here that needs to be tidied up but this is the state of play at the moment):

Dying messiah 5 posts

Jewish Messianism 11 posts

Messiah 17 posts

Messiahs 11 posts

Messianic Judaism 2 posts

Messianism 15 posts

Second Temple messianism 41 posts

And a catch-all category

Messiahs and messianism 95 posts

NC lists different views of the messiah as listed by Armand Abécassis (En vérité je vous le dis):

- the messiah would be a priest (said to be “the Sadducee” view — though I cannot vouch for all of these associations)

- the messiah would be a royal heir of David (said to be “the Pharisee” view)

- the messiah would be a scribe descended from Aaron (said to be an Essene view)

- the messiah was related to a kind of baptist or purification movement (said to be the Boethussian view)

Among the texts of the Dead Sea Scrolls are found at least three different types of messiah

1. the royal messiah, the branch or offspring of David, who is accompanied by a prophetic figure who is an interpreter of the law

2. the priestly messiah, an ideal priest from the line of Aaron

In some scrolls these two messiahs appear together. They are perhaps the idealistic corrective to historical kings and priests who were considered corrupt.

3. a “Son of God” figure, “probably a unique celestial figure”, appears to be divine, without a name assigned although in other manuscripts he is given the name Melchisedech, the agent of divine judgment against evil.

André Paul (whom NC is quoting) concludes that these three messianic figures were part of Jewish thinking in the century or century and a half preceding the time of Jesus of Nazareth.

Pre-Christian Jewish thought about these three different messiahs drew upon Scriptures to flesh out what they were to accomplish. The promise Nathan made to David in 2 Samuel 7 that his throne would endure “forever”, and the prophecy in Isaiah 11:1-5 that a “branch will arise from the stump of Jesse”, and that of Isaiah 61:1 that “he will heal the wounded and revive the dead and proclaim the good news and invite the hungry to feast”, and many others, were applied to their respective messiahs.

One striking example outside the biblical texts is found in the Messianic Apocalypse of the Dead Sea Scrolls. To translate Andre Paul’s observation (quoted by NC):

We are struck by the astonishing relationship between this description of future blessings linked to the coming of the Messiah and Jesus ‘answer to John the Baptist’s question in the Gospels:’ “The blind see, the lame walk ” (Matthew 11, 5 and Luke 7, 22). […] A tradition identifiable in other writings of ancient Judaism serves as their common basis.

The gospel authors were doing what Jewish writers before them had done. They were creating their messiah by pastiching different passages from the Scriptures. The gospels were even copying or incorporating the works of earlier exegetes as we see in the example of the Messianic Apocalypse.

It is these three types of messiah that “Christianity” will unite: Mashiach-Christos, High Priest (in particular in the Epistle to the Hebrews), and Son of Man. It has long been known that in the period of Christianity’s establishment there were struggles over the titles to be given to Jesus Christ. Can we not think that far from depending on different “legends”, the Gospels are midrashim voluntarily composed with a view to celebrating an existing messiah (existing in texts) to unite these divergent expectations? Those who call themselves the disciples of Jesus will make him at the same time the prophet, the priest and the king “thus cumulating all the functions of society and guaranteeing them” (Abécassis p. 290), aided in this by traditions already anchored in the Jewish society of the time.

(Charbonnel, 278, my translation with Google’s help)

We further have texts that have long been known to us, those we label pseudepigrapha. Among these are the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs. Some of these (the Testaments of Levi and Judah) speak of messianic variants: see TLevi ch2 and TJudah ch4.

NC next turns to biblical scholars questing for the historical Jesus and the significance they attach to the contexts of and emphases on different messianic allusions and sayings in the gospels — all in an effort to attempt to discern what Jesus may have thought about himself vis a vis what others (contemporaries, later generations) thought about him. But the whole exercise collapses when one approaches the gospel Jesus as a literary creation woven from the many messianic threads known to Second Temple Judaism.

Both the Messiah Son of David . . . .

The view that the messiah was to be a son of David is well understood: Isaiah 9:5-6; 11:1; Jeremiah 23:5-6; 30:9; etc …; Psalms of Solomon 17:21-43) — even if the details varied somewhat in the different writings. Matthew and Luke make Jesus a genealogical descendant of David; and whereas David was anointed with oil by Samuel Jesus was anointed directly by the Holy Spirit, and so forth.

NC takes us in for a closer look at what it means to be a “Davidic” figure.

First: the name David means Beloved. At Jesus’ baptism we are to hear a voice from heaven declaring Jesus to be God’s Beloved son (Matthew 3:17). (The name given for the Jesus figure in the Ascension of Isaiah is Beloved; further, see the series on Jon Levenson’s book The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son. There we learn that the “Beloved son” is virtually a technical term for an only or firstborn son who is destined for sacrifice. NC does not touch on this work, however.)

That Jesus was resurrected from the dead is another “Davidic” qualification given that a “Psalm of David” was interpreted by early Christians as a prophecy that “David” would not “be abandoned to Hades” — Acts 2:22-23.

(NC does not mention in this context other Davidic features of Jesus such as his ascent to the Mount of Olives in mourning for his life; his suffering of false and cruel persecutions by his former associates and family; his role as a meditative figure. See What might a Davidic Messiah have meant to early Christians?)

What NC does bring out, though, is the link with the nation of Israel itself being named by God as his Beloved. In the Septuagint we find

So Jacob ate and was filled, and the beloved one kicked; he grew fat, he became thick and broad: then he forsook the God that made him, and departed from God his Saviour. — Deut 32:15

And he shall be prince with the beloved one, when the princes of the people are gathered together with the tribes of Israel. — Deut 33:5

There is not any such as the God of the beloved… — Deut 33:26

Thus saith the Lord God that made thee, and he that formed thee from the womb; Thou shalt yet be helped: fear not, my servant Jacob; and beloved Israel, whom I have chosen. — Isa. 44:2

That thy beloved ones may be delivered; … — Psalm 60(59):5

That thy beloved ones may be delivered, save with thy right hand, and hear me. God has spoken in his sanctuary — Psalm 108(107):6

He hath found out all the way of knowledge, and hath given it unto Jacob his servant, and to Israel his beloved. — Baruch 3:36.

Intertestamental literature also speaks of God’s Beloved in connection with the promise for Israel to be restored from captivity (Jeremiah Apocryphon 28; 2 Baruch; the Paraleipomena of Jeremiah 3:8. — links to be added)

Again, we return to Jesus as the embodiment, the personification of his people united with gentiles as well as the embodiment of the multiple messianic views. A god for all seasons.

. . . and the Messiah Son of Joseph

We know that the Jesus of the gospels is the son of Joseph, and Jesus is indeed a “new Joseph” (despised, betrayed, rescued from death, saves his own and foreign people). But NC wants readers to acknowledge what Jewish scholars today say about the biblical story of Joseph and his brothers:

We can also conceive of another reading of this quest for lost fraternity: one that sees in it the typology of the relations between Israel and the Nations. Joseph embodies the Jewish people, jealous, slandered, sold, almost murdered. The rabbis say Israel went through the same trials as Joseph. And then – this is the messianic dimension of Joseph – the time will come when Joseph – the nurturer – will be recognized as such, for the Jewish vocation is to serve humanity. (Translation of NC’s quotation of a passage from Josy Eisenberg and Benno Gross, Un Messie nommé Joseph, p 281)

That is a very striking statement from the perspective we have taken here. Joseph has been interpreted since rabbinical times as a type of messianic figure who represents his people and brings salvation to the nations. This is the Joseph-Jewish people figure that is activated in the gospels in the character of Jesus.

Wait, wait! I hear someone shouting. Doesn’t Daniel Boyarin himself — the Jewish scholar you cite arguing for pre-Christian Jewish beliefs in a slain messiah — insist that there is no evidence for a Messiah son of Joseph in the Second Temple era?

Indeed he does, and NC writes the following in response — and it is a fair outline of Boyarin’s argument. Boyarin is saying (pp 188-89 of The Jewish Gospels) that the earliest record we find of a Messiah son of Joseph is in the late Babylonian Talmud. He suggests that this particular messiah is introduced as a late apologetic to try to avoid the implications of the Jewish tradition (since the Second Temple) having acknowledged that the messiah was to be slain. The idea seems to have been to relegate that view of messiah to a secondary messiah. What Boyarin is arguing is that the Jewish belief in a slain messiah was early, and is found in the earlier Palestinian Talmud. That early slain messiah was originally not some secondary or inferior messiah but in fact “the messiah”.

So is NC justified in speaking of Jesus being shaped in part out of a Messiah of Joseph? She believes the evidence strongly points to such a concept in the gospels and writes, (translated by Google) “Perhaps the circles which wrote our evangelical midrashim innovated precisely by uniting various characteristics never before united in a single character.”

. . .

In 2017 I posted about the “Joseph-messianic” figure:

NC sums up with words from Maurice Mergui’s Un étranger sure le toit:

In the Jewish tradition, the arrival of the Messiah, son of David, must be announced by the appearance of a precursor, of a Messiah son of Joseph, who fights the forces of evil, in order to bring about the salvation of the People of Israel: Following the inevitable defeat of the Messiah of the line of Joseph, the stage will be set for the arrival of the Davidic Messiah. The Messiah son of David is descended from Ruth, a non-Jewish woman who joins the Jewish people, the Messiah son of Joseph on the other hand comes from a Jewish woman who goes to the non-Jews and fights among them for the Jews.

(Google translation, Mergui p. 131, NC p. 282)

The structure is the same as what we saw in the Book of Esther (recall the “Esther-mirror scenario” from an earlier post)

The Joseph / Esther scenario works for the Gospels like a flexible blueprint. It provides the evangelist with elements he can arrange in his own way.

Jesus will be Joseph’s son,

He is even Joseph in person (object of the jealousy of his brothers, he is betrayed and sold like Joseph),

Jesus is hidden (by his mother),

He accepts exile as the place where he will accomplish his mission (Galilee, the northern regions: tsaphon = North = hidden = direction of Exile) — [Another detail is the description of Galilee as being “of the nations” — neil]

He agrees to die to save Israel,

He appears between two robbers, one good, the other bad (like Joseph with Pharaoh’s two servants or Esther with her two maids), […]. “3

(From Mergui, Un étranger, 132 — NC, 282)

And why is Joseph said to be a carpenter, and Jesus the son of a carpenter?

NC points to Marie Vidal‘s suggestion:

According to Matthew, Jesus’ countrymen wonder and wonder if Jesus is not the carpenter’s son. In Hebrew or Aramaic, this name is pronounced ben heroush or ben hérout, and also means son of an engraver or son of freedom. Now the oral Torah repeats “Do not read Engraved, but read Liberty” (Pirkei Avot 6:2).

The word for carpenter here, from what I see in the Strong’s Concordance, can mean a fabricator of any construction with tools. See charash.

Many of us have heard that carpenters or craftsmen were regarded as well educated and capable of solving intricate problems. So a common saying at the time whenever a special difficulty arose was “Is there a carpenter or son of a carpenter among us to solve this problem?”

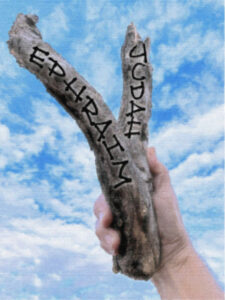

NC proposes that we find a more comprehensive explanation in Ezekiel 37’s discussion of the “stick of wood belonging to Joseph”.

So far then, NC has brought together the literary fabrication of Jesus as encapsulating the kingship of David and the saving role of Joseph. Further, he is also the Messiah-Prophet (the new Moses, the new Elijah, the new Elisha, a “great prophet” (Luke 7:16)), and finally, as will be in covered in a future post, a High Priest.

But what was the purpose of melding the different types of messiah in the literary Jesus?

The union of the various types of Messiah to help reconcile the peoples

In Ezekiel 37:15-22 we see that after the resurrection of the dry bones there is a parable about the divided people becoming one again: the tribes associated with Judah will be united as one with those associated with Joseph. (Judah, of course, is the base for the royal Davidic messiah.)

15 The word of the Lord came to me: 16 “Son of man, take a stick of wood and write on it, ‘Belonging to Judah and the Israelites associated with him.’ Then take another stick of wood, and write on it, ‘Belonging to Joseph (that is, to Ephraim) and all the Israelites associated with him.’ 17 Join them together into one stick so that they will become one in your hand. 18 “When your people ask you, ‘Won’t you tell us what you mean by this?’ 19 say to them, ‘This is what the Sovereign Lord says: I am going to take the stick of Joseph—which is in Ephraim’s hand—and of the Israelite tribes associated with him, and join it to Judah’s stick. I will make them into a single stick of wood, and they will become one in my hand.’ 20 Hold before their eyes the sticks you have written on 21 and say to them, ‘This is what the Sovereign Lord says: I will take the Israelites out of the nations where they have gone. I will gather them from all around and bring them back into their own land. 22 I will make them one nation in the land, on the mountains of Israel. There will be one king over all of them and they will never again be two nations or be divided into two kingdoms.

They will be united as a single piece of wood, or tree — (or cross? — NC suggests most tentatively)

One can imagine from the above parable an idea of uniting two messiahs, one from David and one from Joseph, to cement the union.

But what is of greatest significance is the unification of the royal and priestly messiahs. But that discussion is postponed until a much later chapter when the Passion is examined in depth.

So far once more, then, we have in the gospels a Jesus who is a personification of his people, and therefore as God’s people are his “children” so Jesus, as the personified Israel, is also the Son of God; we have Jesus as the Temple, the divine presence or glory of God’s presence; as the Torah and Interpretation of the Word. As will be seen he is also the High Priestly Messiah, the one to embody the crucified people and the one in whom they will live again. So far NC has been looking at the “horizontal” personifications found in Jesus — the people, the messiahs — and in the next section she surveys the “vertical” personifications — the heavenly figures he represents.

Until then, here are some older posts of mine that delve into Jesus as a representative of the crucified people. They are based on Clarke Owens’ book Son of Yahweh:

- Constructing Jesus and the Gospels: How and Why

- Constructing Jesus and the Gospels: Messianism and Survival post 70 CE

- Jesus’ Crucifixion As Symbol of Destruction of Temple and Judgment on the Jews

Boyarin, Daniel. The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ. New York: The New Press, 2012.

Charbonnel, Nanine. Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier. Paris: Berg International éditeurs, 2017.

Hadas-Lebel, Mireille. Une Histoire Du Messie. Paris: Albin Michel, 2014.

Mergui, Maurice. Un Étranger Sur Le Toit: Les Sources Misdrashiques Des Evangiles. Paris: Editions Nouveaux Savoirs, 2005.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I am fascinated by the Christian obsession on Jesus being some kind, any kind, of messiah. Holding this office in the Jewish religion confirms what upon Jesus for the Christian tradition? To Christians Jesus is not only the son of god, he is god, so why is Jesus being the messiah so important for Christians?

Is great puzzlement.

I suspect it is due to their being the two branches in early Christianity: the Jewish Christians and the Gentile Christians. Being the messiah would mean something to the Jewish Christians, but the Gentile Christians? I can’t imagine.

I think you are right: the term would only have had meaning for the early Jewish Christians. For others it functions at one level as something of an alien label that adds a bit of mystery to the name of Jesus. To later Christians and ever since it has been a term that requires explanation.