I especially loved these words towards the end of the same podcast — I cannot pinpoint a single “straw that broke the back” of my religious beliefs; I look back instead at a series of moments that led me towards atheism. One can also understand why it is so easy to demonize those on “the other side” of a political or religious fence and from there begin to appreciate what it takes for our minds to change.

People are not perfect Bayesian reasoners as much as we would like to aspire to be. People do not have a set of priors that are well delineated and then collect new data and update them according to Bayes’s formula, that’s not what people do. But that doesn’t mean that people don’t change their minds, people change their minds all the time.

1:29:48.7 SC: What often happens is something that can be very familiar to physicists who know about phase transitions, the thing that causes someone to change their mind might not be, and in fact, rarely is the straw that broke the camel’s back. There can be a little thing that they get, the little piece of information and experience, whatever it is, that is associated in time with the moment they change their mind. But the actual cause of them changing their mind is a set of many, many things stretching back in time, okay? You have a person with an opinion, with a belief, a credence in a certain proposition, and they get data that is against that proposition, and data in the very broadest sense, it’s not like they’re being physicists, but they get information, experiences, new stories, conversations with friends, that cause them to think about that particular proposition, and then they don’t change their mind immediately, ’cause that’s not how people work, but that has an effect on them. Even if the effect is invisible at the level of their actual beliefs in propositions, hearing that thing can nevertheless affect them at a deeper level.

1:30:56.8 SC: And if they hear something else, and something else, and something else over a period of time, they can eventually be led to change their mind without it ever being possible to associate the reason for that change with a particular piece of information that they got. Not to mention the fact that often, this data in a very, very broad sense is not data. In other words, the thing that is causing people to change their minds is not some piece of information or some rational argument, but something much more visceral, something much more emotional. Realizing that this person who is a member of a group that they have hated and denigrated for years, they meet a member of that group and become friends with them, suddenly maybe their minds change, right? You are against gay people getting married and then you have a child who turns out to be gay and wants to get married, maybe you change your mind, right? For no especially good reason epistemically, rationally, but you realize that, “I wasn’t really that devoted to that opinion in the first place.”

1:31:55.4 SC: There are many ways to change people’s minds, and it really does happen, and all of this is just to say it’s worth trying. It’s not worth trying reaching out to the extremists, to the crazies, but there are plenty of people who are not like that. There are plenty of people who are just not that devoted. And those people might not be wedded to the views that they very readily profess to believe in right now. This is part of the challenge of democracy, those people count, just as much as the most informed voters count. And of course, there are hyper-informed voters who are extremists on both sides, so it’s not just a matter of information levels, but there are people who are, in principle and in practice, reachable and people who are not, and we should try to reach the ones who are reachable. And again, I would give that advice to the other side as well, if the other side thinks that they wanna reach some people who are on the opposite side, they can try to reach me and I’m here to be reached, right?

1:32:54.6 SC: Change takes time. Often it is not a matter of marshaling better arguments, it’s just setting a good example, providing people with a soft landing. One of the hardest things about changing your mind politically is that it is associated with a million other things in your life, your friendship networks, your families, etcetera, your beliefs about many different things. The joke we had back in George W. Bush’s days, I think Michael Berube was the first person who’ve made this joke, but the joke was, “Well, yeah, I was a life-long Democrat but then 9/11 happened, and now I’m outraged about Chappaquiddick.” The point is, for those of you young people out here, Chappaquiddick was this scandal where Ted Kennedy was in an automobile accident and Mary Jo Kopechne, a woman who was in the car with him, and he plunged into the river and she died, she drowned and he was able to swim to shore, and survived obviously, and continued in the Senate. And Republicans were outraged though, this was like a terrible thing, and Democrats made excuses for it.

1:33:57.7 SC: And the joke being that once you change your tribal political affiliation, your opinion about this historical event changes along with it, because these are connected to each other. And so, I wanna mention this in the opposite way also, so not just that all of these other opinions will change along with you if you do change your mind about something, but that in order to get someone to change their mind, you have to make it seem reasonable for them to live in a whole another world, right? For them to live in a world where a whole set of beliefs are no longer taken for granted in a certain way. That’s what it means by offering a soft landing.

1:34:33.9 SC: One of the very first podcast I did was with Tony Pinn, who was an atheist theologian, who reaches out to black communities and tries to spread the good word of atheism to them. And one of the points he made over and over again is that black people are very religious in part because atheism does not provide them with a soft landing. You can make a rational argument that God doesn’t exist, but they need to figure out a way to live their lives and in the lives of many black communities, religion plays an important role, and if you simply say, “Well, we’re not gonna replace that role, you gotta learn to live with it,” then they’re not gonna be persuaded to go along with you. So part of persuading the other side and reaching out to it is making them feel welcome. And again, I get it if this seems hard to do, if you just want these people to be punished and they don’t deserve it, etcetera, etcetera, I get that, but that’s gonna make living in a democracy harder for all of us, if that’s the attitude we all take.

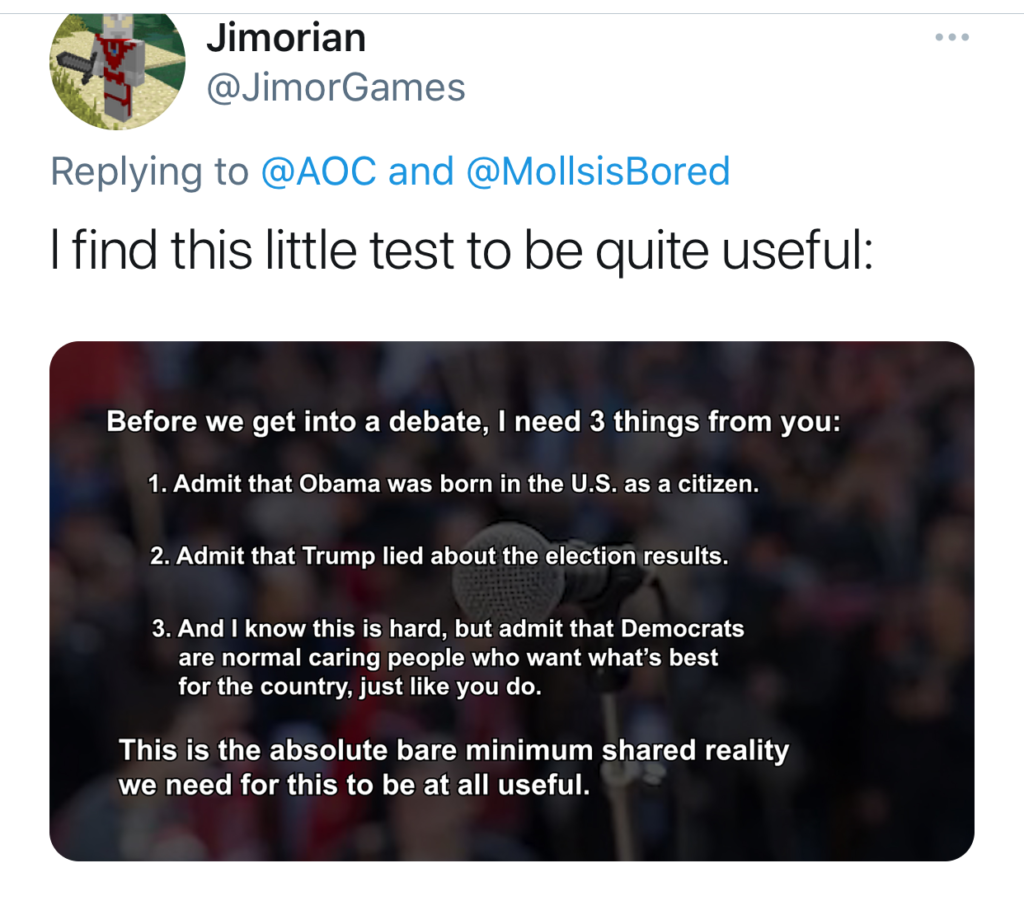

The key takeaway point makes the third point here the one to think about the most: