What follows is not an attempt to explain every person who supports Trump. But if the shoe fits, wear it, as the saying goes. What is uppermost in my mind as I read Post and Doucette’s analysis of the dynamic between a certain kind of charismatic leader and his/her followers is my own experience of strong attachment to a cult leader. Does it fit? Does it seem to apply in non-religious settings? I have posted much about the process of radicalization (especially why people join terrorist groups) and found strong similarities in the psychology involved there and the process of conversion to cults. Let’s see what Post and Doucette say about “the charismatic leader-follower relationship”. This post is a survey of their chapter 7. Bolding and formatting are my own in all quotations. Page references are from the electronic version.

What follows is not an attempt to explain every person who supports Trump. But if the shoe fits, wear it, as the saying goes. What is uppermost in my mind as I read Post and Doucette’s analysis of the dynamic between a certain kind of charismatic leader and his/her followers is my own experience of strong attachment to a cult leader. Does it fit? Does it seem to apply in non-religious settings? I have posted much about the process of radicalization (especially why people join terrorist groups) and found strong similarities in the psychology involved there and the process of conversion to cults. Let’s see what Post and Doucette say about “the charismatic leader-follower relationship”. This post is a survey of their chapter 7. Bolding and formatting are my own in all quotations. Page references are from the electronic version.

Our authors do not believe much can be gained by either a study of the psychology of Trump or the psychology of his followers, but what is of interest is a study of how the two feed off each other, the dynamic between the two.

The relationship between Trump and his hard-line followers represents a charismatic leader-follower relationship, whereby aspects of the leader’s psychology unlock, like a key, aspects of his followers’ psychology.

Remember the Jonestown massacre. Post and Doucette cite work by Abse and Ulman who studied the psychological dynamic between Jim Jones and his followers.

[I]n times of crisis, individuals regress to a state of delegated omnipotence and demand a leader who will rescue them, take care of them.

(p. 110)

I have skipped past Post and Doucette’s analysis of Trump himself so permit me to simply state things will have to be justified in a future post. The idea expressed is that Trump “feeds off the adoration of his followers”. What has led to this type of personality is an “injured self” that finds remedy in the confirmation and admiration of others. Where does an “injured self” come from? Two roads lead to it:

- the individual who has been deprived of mirroring adoration from rejecting parents,

- and a more subtle variant, the individual who has been raised to be special, contingent upon his success.

In the second pathway, a very heavy burden can be placed on a child. Expectation of success can generate troubled insecurity. That’s the kind of person who “feels compelled to display himself to evoke the attention of others.” The attention seeker who is never satisfied, who is constantly seeking new audiences for ongoing recognition.

People who are constantly craving attention and admiration do best when they have the ability “to convey a sense of grandeur, omnipotence, and strength.”

And here’s the hard part for many of us:

Leaders such as Trump, who convey this sense of grandiose omnipotence, are attractive to individuals seeking idealized sources of strength; they convey a sense of conviction and certainty to those who are consumed by doubt and uncertainty.

(p. 111)

I recall the many stories of fellow members of the cult of how “God called” each of us through some crisis in our lives. We were ready for the taking, experiencing doubts and uncertainty.

Now obviously not everyone who goes through a time of “doubt and uncertainty” is going to join a cult or vote for Trump. But it is a factor for many and it is at those times that most of us are vulnerable:

This was evident in Trump’s support from rural areas and the working class, where Trump’s motto “Make American Great Again” (MAGA) had a strong resonance. Despite his lack of any concrete policy, his tweets concerning “JOBS, JOBS, JOBS” had resonated with many of his followers, especially those who are struggling and feel abandoned by the last administration.

(p. 111)

We all see how Trump loves large rallies; even after the election was over he has continued with them. In the cult I don’t think we were disloyal enough to commit the thought-crime that our grandiose leader, “God’s Apostle”, “God’s End-Time Apostle”, was basking in the admiration of his followers even when the stood to applaud whenever he entered and left an auditorium on a speaking tour.

The leader thrives off the admiration of the crowd; his insecurity and self-doubt are buried in it. But the crowds need the leader as much as he needs them.

There is a quality of mutual intoxication for both sides, whereby Trump reassures his followers who in turn reassure him of his self-worth. Even before current rallies, his followers will line up hours early, waiting to fill even sports stadiums that can seat 10,000, continuing to chant “Lock her up!” During the rallies, Trump continues to use his externalizing rhetoric attacking any opponents or focusing on the immigrant crisis, despite calls from fellow Republicans to focus on issues like the economy. But it is this rhetoric that draws in his followers, who chant, “Build the wall! Build the wall!” One can compare it to a hypnotist mesmerizing his audience. But the power of the hypnotist ultimately depends upon the eagerness of their subjects to yield their authority, to cede control of their autonomy, to surrender their will to the hypnotist’s authority.

(p. 112)

The alt-right has been one group at least initially willing to surrender. So long as they see Trump as being on their side concerning “foreigners, Latinos, Muslims”. White supremacist leader Richard Spencer tweeted:

Trump said that he wants to maintain the “nuclear family” by ending chain migration. Basically, he’s implying the superiority of the Protestant “wife and kids” over the South American and African extended family. Interesting rhetoric.

The “dog whistle” has been heard.

It would be simplistic to reduce the entire explanation to “injured” parties finding support in each other’s company.

It is important to note that there are complex socio-cultural, political, and historical factors that must be taken into consideration in addition to the features of the charismatic leader-follower relationship. One of the remarkable aspects of the Trump phenomenon is the stability and psychological power of his followership.

The hypnotic pull of the charismatic leader is compelling for the ideal-hungry follower. The wounded follower feels incomplete by himself and seeks to attach himself to an ideal other. Thus, there is a powerful, almost chemical attraction between the mirror-hungry charismatic leader and the ideal-hungry charismatic follower. And if Trump thrives on the adoring mirroring response of his followers, he provides for them a sense of completeness. Incomplete unto themselves, they have an enduring need to attach themselves to an idealized other.

We wish to emphasize that we assuredly are by no means implying that all those who voted for Donald Trump were narcissistically wounded individuals. But in trying to understand the resilience of Trump’s followership and the core of his base, we are suggesting that Trump’s political personality is particularly appealing to wounded individuals seeking an externalizing leadership and that Trump is particularly talented in appealing to individuals who are seeking a heroic rescuer.

(pp. 113 f)

Sometimes one joins a cult but only for a short time. Once the crisis they are experiencing is no longer troubling them they will likely feel whole and secure enough again to “see through” the cult and walk away. Or as with World War 2, after the Allied victory, Churchill was no longer needed. But there are times when people are more vulnerable than others:

When Trump assured voters in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio that coal mining would be returning, he was sending a rescuing message to a socio-economic bloc that was situationally overwhelmed and needed a powerful rescuer.

Again, as pointed out in the previous post, there are two types of charismatic relationships.

The reparative charismatic leader, as exemplified by Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King, heal the splits in their society as they are healing the splits in their own psychology. The destructive reparative leader, as exemplified by Adolf Hitler, pulls his followers together as he exports hatred to an external enemy. When Trump stimulates the attendees at his rallies to chant in guttural tones “Lock her up!,” this is the hateful rhetoric of the followers of destructive charismatic leaders. It reassures the leader of the powerful support of their followers. And as their chants fill the auditorium, it reassures them that they are followers of a godlike leader who will lead them out of their wounded state, are united in their followership, and will uncritically follow the leader’s call for violence against the protesters.

Religious cult members are known to be ready to cause the deaths of their children, the traumatic breakup of families, and even to kill themselves. It is all done with “purity of heart” in their own minds.

Ulman and Abse in an article not cited by Post and Doucette speak of both followers “regressing” to a previous level of dependency on others that as individuals they had outgrown. They regress to a childlike state in relation to an authoritarian parent when they become part of a larger dynamic. Behaviour they may never have contemplated as individuals they can now, as part of a much greater whole, follow with a full sense of justification.

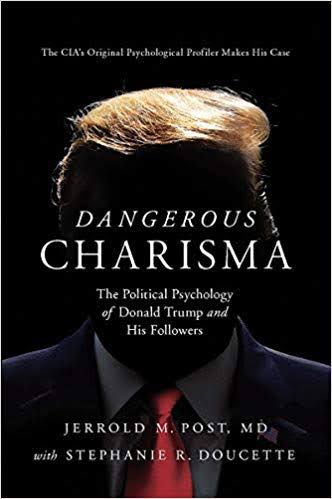

Post, Jerrold, and Stephanie Doucette. 2019. Dangerous Charisma: The Political Psychology of Donald Trump and His Followers. Pegasus Books.

See also on Jstor (though it is written in heavily technical language)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Loki: Is not this simpler? Is this not your natural state? It’s the unspoken truth of humanity, that you crave subjugation. The bright lure of freedom diminishes your life’s joy in a mad scramble for power, for identity. You were made to be ruled. In the end, you will always kneel.

Most recent leaders in the US have been quite narcissistic, George Bush Jr, Barack Obama, they all fed off of a cult of personality. I guarantee the next president will be just the same, Americans and their leaders have become very superficial. Trump loves the lime light, his followers love the show, but he is really nothing but a pied piper, he is leading his followers to nowhere. Fundamentally, nothing has changed, the slow march continues.