Time once more to pull out my copy of Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (Afshon Ostovar). I’ve referred to it a few times now:

Time once more to pull out my copy of Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (Afshon Ostovar). I’ve referred to it a few times now:

- This book looks interesting (2016)

- ISIS on the downhill roll, but… (2016)

- Sleepwalking once again into war, this time nuclear (2016)

- Iran, Iran, if only we had been friends (2018)

- Iran and “the problem of peace” (2019)

Also significant were placards in honor of Qassem Soleimani—the architect of the IRGC’s [= Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corp] foreign operations. Soleimani earned the reputation as a savvy strategist during the US occupation of post-Saddam Iraq, during which he organized an effective counterweight to American influence through the development of a Shiite militant clientage. This work made Soleimani—often referred to with the honorific “Hajj”—a revered figure within IRGC ranks. He was considered the one most directly responding to Iran’s grievances by confronting its enemies on the battlefield. The supreme leader even referred to Soleimani as a “living martyr” for his efforts—placing him iwithin the pantheon of Shiite-Iranian heroes. As one sign proclaimed, “We are all Hajj Qassem!” (p. 3. Highlighting is mine in all quotations)

and

In Iraq . . . Quds chief Qassem Soleimani was able to subvert the influence of the United States by building up a network of pro-Iranian, anti-American Shiite militant groups. These groups fought American and allied troops, and secured powerful positions in Iraq after US combat forces withdrew in 2011. They remain one of the most powerful constituencies in Iraq and have made Iran a dominant player in that country. (p. 6)

After 9/11 Iran was prepared to cooperate with the United States in its war against the Taliban and Al Qaeda in Afghanistan, supplying the U.S. with the detailed location of Taliban and Al Qaeda targets and advising on the best plans for destroying them. Soleimani was said to have been “very pleased” with the cooperation, but then came the Bush led betrayal of Iran and Soleimani’s assistance. The details are posted at

Iran, Iran, if only we had been friends

(2018-09-24)

(I seem to recall another recent betrayal — this time of an Iranian ally that also had a strong record of helping the U.S. defeat ISIS — by Trump.)

Moving on to the period of Iraq’s Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki. . . .

Unable to achieve his goals [to crush the Iraqi Shiite militia opposing the Sunni dominated government] militarily, Al-Maliki was forced to send a team to negotiate a ceasefire with the Basra groups in Qom, Iran. The man behind the deal, as first reported by McClatchy’s Leila Fadel, was Quds Force chief Qassem Soleimani. Part of the agreement included an offer by Maliki to absorb Badr Organization militants into Iraq’s security forces—a move that further entwined pro-Iranian and IRGC-linked elements with the Iraqi government.

Soleimani’s role in the Basra ceasefire highlighted Iran’s growing influence in Iraq. It also signaled Soleimani’s emergence as a powerbroker. Recognizing his own rising stock, in May 2008 Soleimani sent a letter to his “counterpart” in Iraq, US General David Petraeus, suggesting that the two meet to discuss Iraqi security. Petraeus dismissed the letter, but Soleimani’s message was clear: Iran had amassed considerable power in Iraq and would have to be engaged for stability in that country to be achieved. That event was the high watermark of Iranian influence in Iraq during the first half-decade of the US occupation. (p. 174)

Responding to the Collapse of the Soviet Union and Emergence of the Arab Spring

The potential for a fundamental political reorientation in the Middle East was at its most acute since the fall of the Soviet Union. The region was going to change. How and to what end was the question. The Islamic Republic saw peril and opportunity. As Quds Force chief Qassem Soleimani explained in May 2011, the unfoldment of the Arab Spring was as critical to the future of the revolution as the war against Saddam. “Today, Iran’s defeat or victory will not be determined in Mehran or Khorramshahr, but rather, our borders have spread. We must witness victories in Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria.” In order to safeguard its interests and counter its enemies, Tehran had to look beyond its borders. If it failed to help determine the future course of the Middle East, Iran’s enemies would be the beneficiaries.

Soleimani was not speaking rhetorically. He was expressing an evolving view in the IRGC that it not only had the responsibility but the ability to advance Iran’s agenda outside its borders. The IRGC had learned with the fall of Saddam that it could successfully exploit power vacuums for strategic gains. Syria’s civil war and the war against ISIS in Iraq were new entryways for the organization. Under the direction of Soleimani, the IRGC led Iran’s campaigns of assistance in both countries. These were in large part strategic efforts designed to protect Iran’s allies and equities from hostile forces. But their resilience was rooted in religion. The IRGC framed its involvement in both countries in religious terms. In Syria, the IRGC was defending the shrine of Sayyida Zaynab—a mosque built near Damascus that Shiites believe houses the remains of Zaynab bint Ali, a sister of the Imam Husayn and revered hero in Shiism—and in Iraq, it was safeguarding the holy shrines of the imams and the Shia population. As the IRGC saw it, these conflicts were part of a larger war waged by Sunni Arab states and the West against Iran and its allies. It was a war intrinsically against Shiism and the family of the Prophet. To defeat the jihadist scourge and its Sunni Arab benefactors, the IRGC mobilized pro-Iranian, pro-Shiite supporters in Syria and Iraq. These relationships helped Iran advance its agenda and expand its influence. They also intensified sectarian hatreds. (p. 205)

The Critical Importance of Syria

Ostovar explains why Iranian leaders consider Syria to be so critical to their interests:

Tehran could not afford to lose Bashar al-Assad [the Syrian dictator]. The Assad regime was not only Iran’s closest ally, it was fundamental to Iran’s interests in the Western Mediterranean. Support for Hezbollah, Hamas, and the leverage these relationships afforded Tehran vis-à-vis Israel and the United States hinged on having access to Syrian military bases, land routes, airports, and port facilities. It had been through Syria that Iranian-supplied rockets reached Hezbollah in Lebanon— rockets that were effectively deployed against Israel in the 2006 war. Iran had also relied on Syrian intelligence, such as monitoring facilities in the Golan, for information on Israeli military movements, including near the Lebanon border. Even more, many senior Iranian leaders held a deep emotional attachment to the Assad regime. Hafez al-Assad harbored Iranian dissidents before the revolution and facilitated their ties to Palestinian militants in Lebanon. Syria was Iran’s only friend during the Iran-Iraq war, and helped it pressure Saddam during that conflict by cutting off Iraqi oil access to the Mediterranean. As bitterness toward the West and Saudi Arabia hardened during the war, Syria garnered the enduring gratitude of Iran’s leadership. This is especially true for the IRGC, which has overseen Iran’s military ties with Damascus and its relationship with Hezbollah. As Sayyed Hassan Entezari, a mid-ranking IRGC officer who served in Syria during its civil war, explains:

[Bashar] was the one who protected the resistance line in the region and established a connecting bridge between Iran, Hezbollah and Hamas. What Arab country do you know that has provided such a connection for Iran? Syria even supported Iran during the war, even if they were members of the Baath Party. . . . All Arab states embargoed Iran during the war, but it was Hafez al-Assad who stayed beside Iran. We got most of our weaponry through Hafez al-Assad. Nobody can deny this support from al-Assad. He was a supporter of Iran and when this war and intrigue happened to them, how could we abandon them and not support them?

Gradually over the three decades, Syria became a cornerstone of the Islamic Republic’s deterrence strategy. Without access to Syria, Iran’s ability to resupply Hezbollah and threaten Israel would be in jeopardy. If Iran were no longer able to credibly threaten Israel through its clients, then its deterrence efforts vis-à-vis Israel and the United States would be severely degraded. It is unsurprising then that Iran’s leadership saw the unrest in Syria and foreign intervention in support of the rebels as inimical to its strategic interests. Former Basij commander Mehdi Taeb was unambiguous about this point in a September 2013 interview:

Syria is the 35th province and a strategic province for [Iran]… If the enemy attacks and aims to capture both Syria and Khuzestan, our priority would be Syria. Because if we hold on to Syria, we would be able to retake Khuzestan; yet if Syria were lost, we would not be able to keep even Tehran.5

Qassem Soleimani expressed a similar perspective, claiming the movement against Assad was part of a much larger Western plot to sow division in the Middle East and weaken “Iran’s place in the region.” The threat to Syria was existential for Iran. The stakes could not be higher. The IRGC’s response was correspondingly robust. (pp. 205-207)

Recall that “red line” in Syria:

Although [Iran’s] Rouhani brought a change in tone, his policies in Syria were an extension of his predecessor’s. His government maintained the same line: Assad was fighting a war for survival against terrorists, and the West and certain Arab governments were supporting the terrorists to further their own anti-Iran, anti-resistance, pro-Zionist interests. Just weeks into Rouhani’s tenure, Iran was almost thrust into potential conflict with the United States when it appeared Obama might order strikes against Assad after it was determined that Syrian government forces had used chemical weapons against civilians—crossing Obama’s previously stated “red line.” Iranian officials warned against American intervention. IRGC chief Jafari threatened that any US military action against Assad would spark a much wider war in the Middle East. Qassem Soleimani was more explicit, warning: “Syria is our red line. The land of Sham is our ascension to heaven and it will be the graveyard of the Americans.” When Russia stepped in and brokered a deal to destroy Assad’s chemical weapons stockpile via the United Nations, Obama decided against military action. This legitimized Russian and Iranian positions in Syria, and decreased international pressure on the pro-Assad camp. The IRGC continued its course in Syria unaltered. (p. 22)

The Critical Importance of Iraq

Notice, again, Iran’s efforts to eliminate both United Status and Saudi Arabian dominance in Iraq as has been their goal in Syria.

Like in Syria, the Islamic Republic’s involvement in Iraq was in part a strategic decision. Iran had cultivated close ties with Baghdad since the fall of Saddam, and had relied on that relationship to help mitigate its regional alienation. Iraq was an important trading partner for Iran and open to Iranian commercial interests. Iraq had become one of Iran’s closest allies. Speaking on Iran-Iraq ties, Qassem Soleimani said: “Because of [Iran’s] Shiite clerical leadership (marja‘iyyat), Iraq was able to free itself from America’s clutches. If it were not for [Iran’s] clerical leadership, who else could have managed this?” In other words, Iran had intervened to drive out US forces from Iraq and it would do so again with ISIS. Iran had long accused Saudi Arabia and other Arab states of supporting anti-government militants in Iraq and the rise of the Islamic State appeared to be a culmination of that effort. As Ali Saidi, the supreme leader’s representative in the IRGC, explained: “Saudi Arabia tried very hard to ruin the situation in Syria, and Qatar also invested a lot in this situation … Today they feel that all of their conspiracies have failed in Syria. They have started a new front in Iraq.” Iran could not afford to lose its only friend in the region after Syria, nor could it see Iraq conquered by hostile, anti-Iran, anti-Shiite forces. Iran’s long border with Iraq magnified the danger. But Iraq also housed the most important religious shrines in Shiism—sites ISIS was intent on destroying. This made the fight in Iraq more than a strategic or political contest. This was a defense of the family of the Prophet and an existential battle for the future of the Shiite faith. In June, Rouhani made Iran’s pledge firm, saying that it would not “spare any effort” to defend Shiite holy sites. That same month, Qom-based Grand Ayatollah Naser Makarem Shirazi issued a fatwa declaring the fight in Iraq a “jihad,” and making defense of the shrines a religious duty for all Muslims. (p. 223)

Qassem Soleimani’s Role in the Defeat of the Islamic State

The most prominent militias fighting ISIS in Iraq were also those most aligned with Iran’s leadership. The Badr Organization, Kataib Hezbollah, Asaib Ahl al-Haq, and Liwa Abu Fadl al-Abbas quickly became a core part of the Iraqi government’s campaign. . . .

At the helm of all this was Qassem Soleimani, the Quds Force chief. Soleimani was instrumental in facilitating the IRGC’s entrance into the war, and utilized his close ties to Shiite militias and Kurdish forces in coordinating the fight against ISIS. But the rise of the Islamic State was a stain on his legacy, and especially of his handling of the Syrian war. Soleimani helped pro-Assad forces stop major rebel advances, and defend Damascus and Assad strongholds, but this strategy also included ignoring ISIS, allowing it to develop and gain strength. That approach backfired. Soleimani underestimated ISIS, and it now controlled territory from eastern Syria to villages near the Iraq-Iran border. The deteriorating situation must have been worrisome for Soleimani’s bosses in Tehran. Iranian leaders never criticized Soleimani publically, but some signs suggested faith in the seasoned commander might be slipping. . . . .

[I omit the details of apparent attempts to replace Soleimani as the active head of the Quds force.]

. . . . In response to the rumors or actual behind- the-scenes maneuvering against Soleimani, a sudden, almost guerilla public relations campaign emerged with the Quds Force chief as its star. Beginning in September 2014, photographs of Soleimani in the field in Iraq began to be leaked on social media. The images were initially circulated on Facebook pages associated with Iraq’s Shiite militias but quickly spread. The pictures depicted him with Shiite and peshmerga commanders—especially Badr Organization head Hadi al-Ameri—in different battle zones. Others showed him holding firearms, having picnics, praying, shaking hands, and smiling with troops on the front lines. Soleimani was almost always shown in the same uniform: khaki pants, khaki sports cap, black-and-white keffiyeh, and khaki shoes. Sometimes he wore a jacket. Combined with his slight stature, the simple attire gave Soleimani the appearance of a humble, unassuming man. He had an avuncu- lar quality that made him seem a man of the people without detracting from his innate authority. The images became so ubiquitous that a meme developed on social media depicting Soleimani in all sorts of places and with all sorts of people. Soleimani shaking hands with an astronaut on the moon. Soleimani seated behind Jacqueline Kennedy in a presidential motorcade. Soleimani as an attendee—along with Albert Einstein and other Nobel Laureates—of the 1927 Solvay Conference. His personage had gone from relative obscurity to fringe Internet cultural phenomenon in a matter of weeks. Gradually the photos of Soleimani in Iraq began to be picked up by Iranian media as evidence of his exploits—something that suggested his public relations campaign had become endorsed by Iranian officialdom.

This was all incredibly unusual. Prior to the Syrian conflict, Soleimani had maintained a very private profile. He was the leader of Iran’s main covert force and his image fit that role. He was described as shadowy, mysterious, and a master spy. Only a few photographs were even available of him. So the sudden release of dozens of photos over a few months was entirely out of character and appeared to be a very deliberate public relations effort—one seemingly spearheaded by Soleimani’s team and later embraced by Iranian officials. Any rumors of Soleimani’s demise as Iran’s man in Iraq were being instantly and repeatedly repudiated with photographic evidence. Beyond that, a more profound message was being sent: Soleimani—and by extension, Iran—was doing more than any other to assist Iraq. He was literally on the ground, at the front lines, overseeing battles. He was the linchpin bringing together Shia and Kurdish forces to fight a common enemy. When others hesitated, Soleimani acted. He was now more than just a spy chief or organizer of militias. He was the single most important military commander in an international war—something of a mix between Che Guevara and Douglas MacArthur. The same Soleimani who was rebuffed by David Petraeus in 2008 was now essentially occupying the same role as the American general six years later. He was an equal to America’s top commander. Iran was a military power. The world needed to know.

The media campaign was not simply a vanity project. There was substance behind what was being released. Soleimani was on the front lines. He was overseeing joint Shia and Kurdish operations in certain conflict zones. Iraqi officials attested to this. Iranian officials also boasted of Soleimani’s work. IRGC aerospace commander Amir Ali Hajizadeh claimed, for example, that Soleimani with only seventy men had “stopped the advance of Daesh terrorists” into Erbil in the early part of the war. Shia militias and Kurdish forces were beginning to record victories against the Islamic State, and photographs of Soleimani reportedly on the front lines of these battles were released to show his centrality to their success. The first major victory was in the village of Amerli, where Shiite militias and Kurdish peshmerga succeeded in driving out Islamic State forces. The campaign benefited from US air support, which was most likely coordinated through the Kurds, but the militias and peshmerga did the heavy lifting. Shiite and Kurdish forces under Soleimani’s command had similar success driving out the Islamic State from the eastern Diyala villages of Jalawla and Saadia, roughly twenty miles from the Iranian border. These battles included the first reported use of Iranian F-4 military aircraft, which provided air support for the ground forces. The use of the F-4s was an escalation probably prompted by the proximity of the fighting to Iran’s borders. It was a bold assertion of Iran’s place in the war. Regardless of frequency or effect, Iranian air assets were operating in Iraq in a manner parallel to that of US and allied air forces. Western pundits saw this as evidence of direct US-Iranian coordination. Both countries denied this, but in December 2014 Secretary of State John Kerry described the impact of Iran’s military contributions as having a “positive” net effect in the broader war against the Islamic State.

Iran was a formidable player in the war because of Soleimani. His close association with Shiite militias, however, was a mixed blessing. On the one hand, these relationships provided Iran credibility and influence in Iraq. Shared religious identity and ideological commitments gave Iran a strong connection to its Shiite clients, and a position in the war unmatched by other outside powers. It also gave the impression that Iran was pursuing a sectarian agenda. Support for Assad was based on friendship and politics, but Sunni Arabs saw it as a Shiite alliance against them. It did not matter that Assad’s Baathist regime was secular . . . (pp. 224-228)

Ostovar, Afshon. Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

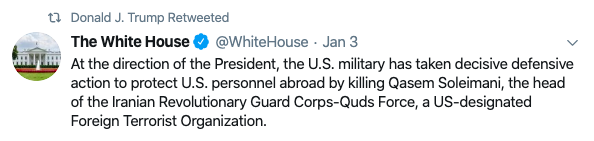

One thought on “Who was Qassem Soleimani?”