I have been slow posting with the first few pages of M. David Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History but I hope the time I’ve taken with the foundations (see various recent posts on ancient historians) will pay off when I get into the main argument. A reason I have taken a detour with readings of ancient Greco-Roman historians is the difficulty I have had with some of Litwa’s explanations in his introductory chapter. Was I reading contradictions or was I simply not understanding? I’m still not entirely sure so I’ll leave you to think it through.

I have been slow posting with the first few pages of M. David Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History but I hope the time I’ve taken with the foundations (see various recent posts on ancient historians) will pay off when I get into the main argument. A reason I have taken a detour with readings of ancient Greco-Roman historians is the difficulty I have had with some of Litwa’s explanations in his introductory chapter. Was I reading contradictions or was I simply not understanding? I’m still not entirely sure so I’ll leave you to think it through.

Litwa will set out a case that educated non-Christians would have read the gospels as a certain type of history:

I propose that educated non-Christian readers in the Greco-Roman world would have viewed the gospels as something like mythical historiographies—records of actually occurring events that nonetheless included fantastical elements. . . . There was at the time an independent interest in the literature of paradoxography, or wonder tales.67 Literature that recounted unusual events especially about eastern sages would not have been automatically rejected as unhistorical.

Even as the evangelists recounted the awe-inspiring wonders of their hero, they managed to keep their stories within the flexible bounds of historiography. They were thus able to provide the best of both worlds: an entertaining narrative that, for all its marvels, still appeared to be a record of actual events. In other words, even as the evangelists preserved fantastical elements (to mythödes) in their narratives, they maintained a kind of baseline plausibility to gesture toward the cultured readers of their time.

67 – the citation is to mid-second century records

(Litwa, 12. Bolding and formatting are mine in all quotations)

I interpret this particular comment to mean that the gospel narratives were similar to other historical writings of the time insofar as they sprinkled a tale of “normal” (i.e. plausible) human activities with stories of miracles and wonders. That is, the main (“normal”, “plausible”) narrative (represented by green blocks) flows independently of the sporadic wonder tales (purple with sun disc). The wonder tales add entertainment but the story itself does not depend on them. They can be omitted without any damage to the main narrative.

Examples in Greco-Roman histories: where an author inserts a tale that “they say” but leaves it open to the reader whether to believe it or not. For some examples, see The Relationship between Myth and History among Ancient Authors. Usually the “wonder story” is only loosely integrated into the larger realistic account by rhetorical devices such as “they say” or “there is a story that” or “poets have written” or “a less realistic account that is well known…” etcetera.

Examples in noncanonical gospels: Jesus being “born” by suddenly appearing beside Mary after a two-month pregnancy (Ascension of Isaiah); Jesus causing clay pigeons to come alive (Infancy Gospel of Thomas). . . . Tales of wonder that entertain as interludes rather than drive the plot.

In the canonical gospels, on the other hand, miracles are an essential part of the respective plots. To see how true this is, try reading the Gospel of Mark after first deleting or covering up the episodes of the miraculous, the divine or spirit world, mind-reading, and other supernatural inferences. One is left with a story that makes no sense. Was it because of an argument over unwashed hands that Jesus was crucified, for example? In the canonical gospels, the miracles are essential to the plot development: they are what bring notoriety to Jesus and identify him as the one whom the priests must, through jealousy, get rid of. The gospel narratives simply don’t work as stories without Jesus’ ability to perform miracles and demonstrate (though he is not obviously recognized as such by the human actors) his divine nature. The Greco-Roman histories would lose some entertainment value by omitting certain miracles but their fundamental narratives would still survive.

The tales of wonder in the gospels are (1) rich with theological meaning (e.g. feeding multitudes in the wilderness represents a “greater Moses” or shepherd role of Jesus) and (2) integral to the plot (e.g. the miracles set in train the events that lead to the atoning death of Jesus).

Hence I find Litwa’s thesis difficult to accept in the light of what we know of Greco-Roman histories. In the gospels, the tales of wonder themselves must be understood as the historical events, essential to the historical narrative, not optional entertainment along the way. There are not “two worlds” in the gospels, mundane and wonders, but one world in which the wonders are as essentially historical as the preaching and the debates.

A Better Comparison?

If the gospels are to be compared with a form of historiography I suggest it is not with Greco-Roman works but with Jewish scriptures, the historical books, such as Genesis to 2 Kings or the Primary History. There the tales of miracles and divine interventions are told as matter-of-factly as the tales of famines and of armies in battle. That’s where we find narratives closest to the canonical gospels. Perhaps we can extend the comparison of our gospels to other Jewish works likewise influenced by the books of the Primary History.

Towards the end of this chapter Litwa points to a characteristic of the gospels that I think supports the closer comparison with Jewish historical narratives.

Another Inexact Comparison

In the next section Litwa appears to be suggesting something different, however:

“Ancient Greeks and Romans were led to historicize their mythography because they viewed it as a record of the past. Over the course of time, however (sic), the description of past events had been distorted to add a divine aura to ancient deeds.”

With the “however” in the second sentence Litwa appears to suggest a subsequent development to an earlier “historicizing” of myths, but the sentence instead describes a mythicizing of history. That should have been the point of the first sentence. There seems to be something amiss in the flow of thought here.

Ancient Greeks and Romans were led to historicize their mythography because they viewed it as a record of the past. Over the course of time, however, the description of past events had been distorted to add a divine aura to ancient deeds. Great heroes, it was thought, were given divine parents to explain the magnificence of their accomplishments. Battles along rivers were turned into the one-on-one combats of heroes and river gods. In the fourth century BCE, the Greek writer Palaephatus made the general remark,

“The poets and story writers [logographoi] have converted some events into unbelievable and incredible tales in order to inspire human wonder.”

Closer to the time of the gospels, Strabo opined that

“the tellers of mythoi, and most of all Homer, do not tell mythoi in all they say, but for the most part weave in mythoi as supplementary material [prosmytheuousi].”

A generation or so after the evangelists, Pausanias observed,

“The same people who enjoy listening to mythical tales [mythologemasin] are naturally disposed to invest them with fantastical elements [epiterateuesthai].”

As a result of this basic supposition (that stories are mythicized or made more fantastical over time), ancient literary critics thought they could historicize mythography and in this way “restore” it to its original form.

Now whether this mythicization of stories actually happened—at least on any large scale—is a matter of debate. Yet there is a case of mythologizing that will provide an instructive digression here. It comes from a satire . . . .

(Litwa, 13)

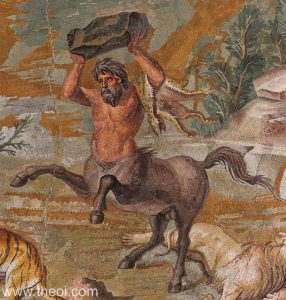

When Palaephatus writes of “wonders” he does so for the express purpose of explaining why he believes they have nothing miraculous in their origin at all. So when he talks about the myth of Centaurs it is only to argue that the myth was entirely natural:

When Palaephatus writes of “wonders” he does so for the express purpose of explaining why he believes they have nothing miraculous in their origin at all. So when he talks about the myth of Centaurs it is only to argue that the myth was entirely natural:

Now some people . . . are too credulous and believe everything that is said to them. Others, of a more subtle and inquisitive nature, totally disbelieve that any of these tales ever happened. My own belief is that there is a reality behind all stories. For names alone without stories would hardly have arisen: first there must have been deeds and thereafter stories about them.

As for the many forms and monstrous shapes which have been described as once having existed, but which now do not exist — these, I believe, did not exist in the past either. For anything which ever existed in the past exists now in the present and will exist hereafter. . . . But the poets and early historians in order to astonish people have turned certain past events into unbelievable and wonderful tales. Now I know that such tales cannot be true, but at the same time I understand that there would not be stories if there were not real events behind them.

Here is how the same author “speculated” (he says he toured the world and spoke to all sorts of people, especially the “elders”, to learn the “truth”) the myth of the centaurs originated:

. . . But even if there are some people who believe that such a beast once existed, it is impossible. Horse and human natures are not compatible, nor are their foods the same: what a horse eats could not pass through the mouth and throat of a man. And if there ever was such a shape, it would also exist today. The truth is as follows.

In the days when Ixion was the king of Thessaly, there was a herd of wild bulls on Mt. Pelion, which made the mountain range impassable. The bulls would come down into the inhabited areas and lay waste the orchards and crops and destroy the livestock. So Ixion made a public proclamation that he would reward with a great deal of money any man who killed the bulls. Some young men from the foothills . . . got the idea of training their horses to carry riders: previously horseback riding was unknown; people only used horses with chariots. But these young men mounted their horses and rode them to where the bulls were: there they attacked and hurled their javelins at the herd. . . . [T]hey eventually killed the bulls and won for themselves the name “Centaurs”, because “they stuck the bulls.” [kent– = to prick; tauros = bull].

So the Centaurs got their money from Ixion, but pride in their wealth and their achievement caused them to become insolent: they engaged in many wicked deeds, in particular against Ixion himself. . . . [T]he Centaurs became drunk and carried off the wives . . . ; they put the women on their horses and fled back to their own homes. . . . Now as they were riding off, all that was visible to those who watched them from a distance was the back of the horse without the head and the top part of the man without the legs. The sight was a strange one, and people said: “Its . . . Centaurs who are overrunning us!” From the shape they saw and the words they said the unbelievable myth was fashioned . . . .

(Palaephatus, 29-32)

A Gospel comparison would be if we read that Jesus did not walk on water but there happened to be a sandbank hidden just beneath the waves and so it only looked like he walked on water. Rationalizations like that would, of course, rob the gospels of all their meaning.

As for Strabo and Pausanias, again, I think by now we can see that their descriptions do not match what we read in the gospels.

But as indicated above, Litwa will give a reason for this difference between the gospels and ancient Greco-Roman historiography.

How Were Tales of Wonder Thought to Originate?

Litwa uses the satirist Lucian’s account of the Death of Peregrinus for its explanation of how tales of miracles were thought to arise. From Lucian he notes a four-step development:

- Storytellers were known to love adding wondrous elements to a tale for the sake of entertaining listeners.

- The more gullible hearers would accept the tales as true and as the embellished tale was retold more people would come to believe it, even those not thought of as gullible, even wise and experienced people could believe it.

- Such tales could spread with lightning speed. . .

- Even recent events could be adorned with fantastic extras, especially if they depicted a modern person acting out an ancient mythic hero (72)

- It mattered not that a real person was the centre of the story; even a real person could become “mythologized”.

Such might be the model of how mythical tales emerge and spread according to Lucian and “common wisdom”, but I think we are entitled to question its plausibility.

- Were the miracles added to the life of Jesus for entertainment value, to make his shaman status sound much more dramatic than stories of other shamans?

- How likely is it, for example, for the more sophisticated classes to embrace a story because of the numbers of “gullible” increase?

How likely is such a model to explain the canonical gospels emerging late in the first century? It may work, but it surely needs testing, careful thought, before going along with it.

Restoring the Core?

Litwa proceeds to call upon Origen’s comparisons of Greek myths:

Before we begin our reply, we have to remark that the endeavour to show, with regard to almost any history, however true, that it actually occurred, and to produce an intelligent conception regarding it, is one of the most difficult undertakings that can be attempted, and is in some instances an impossibility. For suppose that some one were to assert that there never had been any Trojan War, chiefly on account of the impossible narrative interwoven therewith, about a certain Achilles being the son of a sea-goddess Thetis and of a man Peleus, or Sarpedon being the son of Zeus, or Ascalaphus and Ialmenus the sons of Ares, or Æneas that of Aphrodite, how should we prove that such was the case, especially under the weight of the fiction attached, I know not how, to the universally prevalent opinion that there was really a war in Ilium between Greeks and Trojans?

And suppose, also, that some one disbelieved the story of Œdipus and Jocasta, and of their two sons Eteocles and Polynices, because the sphinx, a kind of half-virgin, was introduced into the narrative, how should we demonstrate the reality of such a thing? And in like manner also with the history of the Epigoni, although there is no such marvellous event interwoven with it, or with the return of the Heracleidæ, or countless other historical events. But he who deals candidly with histories, and would wish to keep himself also from being imposed upon by them, will exercise his judgment as to what statements he will give his assent to, and what he will accept figuratively, seeking to discover the meaning of the authors of such inventions, and from what statements he will withhold his belief, as having been written for the gratification of certain individuals. And we have said this by way of anticipation respecting the whole history related in the Gospels concerning Jesus, not as inviting men of acuteness to a simple and unreasoning faith, but wishing to show that there is need of candour in those who are to read, and of much investigation, and, so to speak, of insight into the meaning of the writers, that the object with which each event has been recorded may be discovered.

(Origen Against Celsus, 1.42)

I imagine some readers might pause and ask if they are meant to understand that the historical Jesus has the same sort of basis as the historicity of the Trojan War (universally prevalent opinion) or the historicity of the return of the sons of Heracles.

So when Litwa explains that . . .

The ancients were willing to believe the historicity of their mythography, and they were fairly confident that they could distinguish the mythical elements from the historical core. Therefore, to make the mythoi believable, experienced historians could put them back “into historical form” . . .

(Litwa, 15)

. . . we must pause again and wonder how that concept applies to the canonical gospels. There were gnostic attempts to convert gospel stories to parables or coded symbolic tales; and the Gospel of Mark can be argued as being essentially a full scale narrative parable, but most of us would find it difficult to accept that such views of the gospels held any deep and widespread traction in antiquity.

Uniformity – the Principle of Historicization

Litwa brings out the point I made above about Palaephatus working to reduce explanations for mythical tales to ordinary and universal human events. He is right to do so, but I expect in later chapters it may become clearer how this comparison relates to the canonical gospels.

Litwa cites a historian of ancient history, Gary Forsythe, and I will also quote him. He is discussing the way the ancient historian Livy handled acts of divinities in his history of Rome:

One thing commonly shared among them is that Livy never attaches a miraculous element to these issues. The Fates, the Fortune of the Roman people, and the gods are viewed as having guided the course of human affairs through their normal operation. Thus, Livy appears to have been a theist who believed that the gods could and did influence the outcome of human events, but that they did so impersonally without transgressing nature’s laws. …… In addition, Kajanto is correct in concluding that in the Livian world view history is largely determined by the actions of men, not of the gods or of Fortune. As Livy stresses in s.9 of the praefatio, Rome acquired its empire through the virtues of its citizenry, not as the fortuitous gift of the gods or of fickle Fortune.17

(Forsythe, 93)

Again, we see contrast, not comparison, with the gospels. We must wait for Litwa’s explanation.

Litwa then cites Charles William Fornara, apparently to support the idea that ancient historiography could testify that “miracles could still happen”:

Miracles could still happen, to be sure, but they were not viewed as violations of nature. They designated divinely caused events that—because they were unusual and magnificent—inspired wonder or fear. To quote the author of Airs Waters Places (written about 400 BCE),

“I too am quite ready to admit that these phenomena [the inflictions of disease] are caused by god, but I take the same view about all phenomena and hold that no single phenomenon is more or less divine in origin than any other. All are uniform, and all may be divine, but each phenomenon obeys a law, and natural law knows no exceptions.”

(Litwa 16)

Such an assertion is surely a redefinition of a miracle in a way that it loses all meaning. What the ancient author is saying is that miracles do not happen but that gods do guide human events. If a miracle is redefined as a god guiding human events in a way to achieve divine will then we have something quite different indeed from what is considered a miracle in the canonical gospels. To quote Fornara in full:

One only was excepted, the supernatural, for belief in divinity had become irrelevant to historical explanation. As the author of Airs Waters Places affirmed of certain Scythians,

The natives believe that this disease is sent by God, and they reverence and worship its victims, in fear of being stricken by it themselves. I too am quite ready to admit that these phenomena are caused by God, but I take the same view about all phenomena and hold that no single phenomenon is more or less divine in origin than any other. All are uniform and all may be divine, but each phenomenon obeys a law, and natural law knows no exceptions.

(Fornara, 81)

Surely so far all of Litwa’s attempts to compare the canonical gospels to Greco-Roman historiography — and that is how I have interpreted his discussion, hopefully correctly — have stumbled somewhat over the way the tales of divine miracles are treated.

Further Examples of Historicization

Litwa presents more examples but unless I am missing a key point of his argument I fear they, too, leave a reader doubtful that the gospels are going to fare well by comparison. I am still waiting to read Litwa’s discussion of the differences that clearly arise.

One further instance is Dionysius of Halicarnassus and his discussion of an adventure of Heracles. (See our earlier quotation of Dionysius’s account in greater detail at The Relationship between Myth and History among Ancient Authors.) Litwa concludes:

One can see how elements in the second “historical” story correspond to parts of the “mythical” account. Heracles changes from a lone ranger to a powerful general; his nap in the field corresponds to his army sleeping on the plain; the stolen cattle correspond to the plunder taken by Cacus’s men; and the rocky fortress (later demolished) corresponds to Cacus’s original cave. Whoever historicized the mythos (perhaps Dionysius himself) made a significant effort to reinterpret the original story and make it more plausible in relation to the geopolitical conditions of the time. In essence, Heracles the maverick demigod becomes a model Roman general.

(Litwa, 17)

Plutarch’s accounts of Romulus and Remus being reared by a wolf and Theseus daring to fight and slay the Minotaur are further illustrations. A prostitute was called a she-wolf so we can more rationally find the origin of Romulus and Remus in that train of thought, and the Minotaur more likely developed from a story of a vast labyrinth — so Plutarch explains.

Is Litwa here suggesting that the stories of Jesus’ miracles arose in a manner not unlike the way myths emerged from a historical Heracles, or from a historical Romulus and a historical Theseus? If so, one can begin to suggest specific problems with such a thesis.

Litwa does add, however, that

Educated readers had trouble believing that these events happened (see chapter 12).

(Litwa, 18)

I look forward to reading chapter 12. If the gospels were written with an increasingly educated audience in mind, since, as Litwa has already pointed out, more sophisticated members were joining the churches, then I would think the way they are written, so unlike the way miracles are treated in the relevant Greco-Roman literature, would be counter-productive.

Historicization and the Gospels

“Jesus performed many human, or human-like, activities” —

I am left wondering what Litwa means by “or human-like” activities. How are these different from “human” activities? Is Litwa hinting that even modern readers must accept that Jesus really did perform miracles, something more than “human-like” activities?

But don’t misunderstand. Litwa certainly acknowledges differences between the gospels and Greco-Roman historie and he finally attempts to account for this difference in the context of all the above comparisons:

The evangelists were both similar to and different from these histori- cizers. They were different in that, by and large, they did not need to historicize their narratives of Jesus. Jesus performed many human, or human-like, activities; and many of his miracles could stand because of assumptions about his divine nature.

(Litwa, 18)

This statement, or explanation, pulls me up to try to think it through before proceeding. So Jesus is presumed to be, a priori, a divine man, unlike Heracles or Romulus or Theseus, — or the “first Centaurs”, etc. Does this not mean that the gospels are not about a historical character at all according to the Greco-Roman context? Is not that what all the historiographical samples Litwa has pulled out must tell us? Does not this assumption preclude the possibility of any comparison with the above “pagan” examples of historiography? Given those assumptions, there was no possibility that the stories began with Jesus walking on a sandbank or acting like any other shaman. There was no ballooning of mundane events. The assumptions of divine nature meant that Jesus’ miracles were seen as miracles in much the way they are narrated — from the get-go.

If so, then does it not follow that the stories are not meant to prove Jesus’ divinity? They are surely not written for outsiders but for believers. I can accept that conclusion but I am not sure many other students of the gospels would agree with it. Given what has been shown us about the nature of ancient Greco-Roman historiography it should be evident that most educated readers would simply dismiss the gospels as fables for the gullible.

Or am I mistaken here?

So much for the difference. But in what way are the gospels also “similar”?

Yet there is an underlying similarity in the way the evangelists and the Greco-Roman historicizers operated. Like the historicizers, the evangelists did not let the stories of Jesus appear as fables. They deliberately put the life of Jesus into historiographical form. They did so, I propose, for the same motives that contemporary Greco-Roman historians historicized their mythography: to make their narratives seem as plausible as possible.

(Litwa, 19)

I hope to find clarification further into the book. When Greco-Roman historians put “myths” into “historical form” they expressed them with some critical distance from them and so allowing the reader to decide if they should be believed or not; and the authors usually strongly hinted that they should not be believed as myths. More plausible explanations lay behind the myths. Or the gods merely directed human affairs without performing any real miracles. That is the fairly constant message that I think Litwa has himself demonstrated.

The Roadmap

M. David Litwa promises to work out the above thesis in the rest of the book. The introduction has left me with many difficult questions so I look forward to reading his further discussion. Litwa also says he will clarify how his thesis differs from the Jesus Myth theory. That proposal does leave me disappointed because I don’t see the point given that Litwa earlier made it clear that his thesis has nothing to do with the historicity of the events in the gospels. (We have also recently seen that both Richard Carrier and Raphael Lataster place no overwhelming weight on the gospels as evidence for or against the historicity of Jesus. Both say that the gospels could be used either to argue for “mythicism” or “historicism”.) I am much more looking forward to his promise to show how the gospels conform to “mythic historiography of the early Roman empire”. Finally there appears to be an apologetic twist at the end:

The book concludes with reflections on myth and historiography in the modern world, specifically why modern Christian believers still consider the gospels’ presumed historicity as a necessary support of Christian truth.

(Litwa, 19)

So now that we have completed such a lengthy set of posts to cover merely the introduction, let’s get into the main arguments. (Oh, but we have to tackle something about the Christ Myth theory first, the relevance I which I cannot understand, unless one wants to establish apologetic credentials, perhaps.)

Fornara, Charles William. 1983. Nature of History in Ancient Greece and Rome. University of California Pre.

Forsythe, Gary. 1999. Livy and Early Rome: A Study in Historical Method and Judgment. Franz Steiner Verlag.

Litwa, M. David. 2019. How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

. . .

Origen. 1869. “Contra Celsum.” In The Writings of Origen. Vol. 2, translated by Frederick Crombie. Edinburgh : T. & T. Clark.

Palaephatus. 1996. On Unbelievable Tales = Peri Apiston: With Notes and Greek Text from the 1902 B.g. Teubner Edition. Translated by Jacob Stern. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers.

| To order a copy of How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths at the Footprint Books Website with a 15% discount click here or visit www.footprint.com.au

Please use discount voucher code BCLUB19 at the checkout to apply the discount. |

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I’m a little confused

“Yet there is an underlying similarity in the way the evangelists and the Greco-Roman historicizers operated. Like the historicizers, the evangelists did not let the stories of Jesus appear as fables. They deliberately put the life of Jesus into historiographical form. They did so, I propose, for the same motives that contemporary Greco-Roman historians historicized their mythography: to make their narratives seem as plausible as possible.”

and

“Litwa earlier made it clear that his thesis has nothing to do with the historicity of the events in the gospels.”

I think this means he isn’t going to argue that any of the events described had (or needed to have) a historical basis, but am not sure if I am reading that right

I have been working through a whole series of apparent contradictions and inconsistencies in Litwa’s presentation of his case in his Introduction chapter. That’s the principle reason I have paused to read and re-read several ancient historians and post about them along the way.

You are correct to raise the confusion you have. Greco-Roman historians presented mythical characters in historiographical form by removing all the fantastical elements of the myths associated with them. That’s NOT how Jesus is presented.

The Gospels do NOT historicize the myths; the Gospels do NOT make their narratives seem as plausible as possible. At the end of the chapter Litwa “admits” that the Gospels appear to justify their MYTHICAL presentation of Jesus on the basis that they believed Jesus from the very outset was a DIVINE man! That is NOT how Heracles was presented as a historical person, or his deeds presented as consistent with any sort of historical narrative.

If you are confused by what I try to explain about Litwa’s argument it is because I also am confused even as I try to document it here as honestly, as directly, as simply and forthrightly as possible.

I really hope to find something more consistent with the evidence presented in future chapters. But at this moment I am as confused as you are.

These postings are driving me crazy, because this is all so relevant to the book I’m working on. But the benefit it this helps motivate me to work faster :p

“I propose that educated non-Christian readers in the Greco-Roman world would have viewed the gospels as something like mythical historiographies—records of actually occurring events that nonetheless included fantastical elements. . . . There was at the time an independent interest in the literature of paradoxography, or wonder tales.67 Literature that recounted unusual events especially about eastern sages would not have been automatically rejected as unhistorical.”

Yes, I agree with this. But at the same time, what we see when we look into paradoxography is that many of the tales are complete fabrications. Paradoxography was not historiography, but yet those stories were also believed.

It seems, from what you’ve posted, that what Litwa is missing is the role of prophecy in all this. This of course is what I focus on in my book, and I really work everything around the roll of prophecy in both practice and literature. I think so much of what’s being missed in what you’ve discussed so far is greatly illuminated by the role of prophecy. In many cases, prophecies were used to actually make accounts more “believable”.

A key thing to understand is that, of course, not everyone viewed everything the same way. No doubt Cicero would have scoffed at the Gospels, yet many people believed many things that Cicero found absurd. Yes, there were histories being written, but histories weren’t the only things that people believed to be true, even many scholars. Of course we know that the Stoics, the main school of thought at the time, believed in many miracles and prophecies and all manner of nonsense, despite being well educated.

Prophecies played a primary role in Roman politics and many accounts of various prophetic stories were taken extremely seriously by the Senate, and many such accounts looked very similar to Gospel accounts. These were not critical histories, but rather field reports of some wonder having taken place or some prophecy having been uttered or played out, etc. and the Roman Senate took actions based on these accounts. This is what I go over in my book.

But what we see when we dig into many of these other prophetic and miraculous tales is that they too were total fabrications. And yet these total fabrications were widely believed as true, even to the extent of influencing the action of the Senate and later emperors.

We can’t just hold Pausanias out as the model and claim that anything less than his level of sophistication was not deemed reliable and would have been discounted. Many stories were believed as true without being in the form of historiographies. One did not need to write historiographically in order to write accounts that would be widely perceived as true. They may have been scoffed at by the likes of Cicero or Cassius Dio, but that wasn’t the target audience.

I think, as you know, that Mark was writing fictional allegory, and that Matthew, Luke and John did all attempt to historicize Mark. But they seem to have been bound for some reason not to stray too far from Mark, and thus that is why they didn’t take on the genre of historiography. They certainly weren’t critical redactors of Mark from a skeptical perspective. The only critique of Mark is theological. It is clear that the later writers take Mark and make efforts to endorse the miracles and even add more. They take what are really allegorical vignettes and give them literal framing. They take allegory and present it literally. So if the question is, why didn’t they do a better job at it, I suppose the answer is that they didn’t need to because that’s not what was needed for their target audience.

“They are surely not written for outsiders but for believers. …it should be evident that most educated readers would simply dismiss the gospels as fables for the gullible.

Or am I mistaken here?”

I think so. Remember that many apologists were educated readers. They all believed these stories. And it is clear that their introduction to Christianity is through these stories.

Look at today. Look at highly educated people who believe total nonsense. It was no different back then. I don’t think the Gospels, any of them, were written for “existing Christians”. I think they were all written to introduce people to Jesus who had never heard of him before. There would have been no Christian people who already conceived of Jesus according to the Gospels when they were being written.

All we have to do is look at all of the conflicts between the Stoics and others to see that many people believed nonsense. I think maybe you’ve become biased by the intellectual giants of antiquity. Certainly there were very intelligent and critical thinkers who wouldn’t have entertained these fables. I mean the supposed Trypho is a perfect example. But those were the minority, even among the educated. All we have to do is look at the Roman Senate which made decisions based on the reading of livers from sacrificial animals and the flight patterns of birds. Serious decisions, even with self-defeating conclusions, were agreed to by the Senate based on prophecies and the reading of omens. Roman Senators weren’t uncouth hoi polloi.

So anyway, I find the subject fascinating and I can’t wait to get my book finished to contribute to it.

Neil writes: “Hence I find Litwa’s thesis difficult to accept in the light of what we know of Greco-Roman histories. In the gospels, the tales of wonder themselves must be understood as the historical events, essential to the historical narrative, not optional entertainment along the way. There are not “two worlds” in the gospels, mundane and wonders, but one world in which the wonders are as essentially historical as the preaching and the debates.”

I agree with this critique. In GMark, it is Jesus’s ability to sway the multitudes via his teaching and his miracles that discomfits the Council and causes them to keep tabs on him. The story is a standard dramatic plot: a charismatic outsider (here, who does miracles and teaches) poses a challenge to the authorities of the status quo. What will the authorities do? Will he succeed?

Regarding how educated non-Christians would have understood/read the canonical gospels, the answer is not at all simple. Each person was different, and occupied a different place in an ever-changing Christian landscape. When are they alive? Where are they?—this affects the Christianities they already know about. And individually, how much do they know about “Christianity” outside the four-gospel story?

I think Litwa is assuming that the four-gospel story was educated pagans’ introduction to Christianity. He may be extrapolating backward the orthodox position that Christianity started with the four-gospel story, and spread from there. Actually, people in antiquity had Christian beliefs prior to and outside the four-gospel story. (That’s why orthodoxy had to catholicize the Letters of Paul and canonize other nongospel texts.) Educated non-Christians would have known that Christianity was bigger than the four-gospel story! Certainly, in the second century, an educated non-Christian would perceive “Christianity” as a philosophical cult illustrated by the four-gospel story. As time went on, the four-gospel story became more central (see next paragraph), but I think that some educated non-Christians (and some Christians) would continue for many centuries to maintain the distinction: The uneducated took the stories literally, the educated understood them symbolically.

Simultaneously, uneducated (that is, illiterate or craft-literate) non-Christians were taking the four-gospel story literally. So were children who were brought up as Christians. So there was a movement from below to treat the story as true history, regardless of how educated people perceived it. (This movement, I think, did not cause the orthodox redefinition of the gospels as the biographies of Jesus of Nazareth, but certainly fuelled it once created.) As time went on, church leaders had to satisfy both kinds of believers and moved their doctrine accordingly.

Back to educated pagans’ perception of the four-gospel story. The four-gospel story is inherently dramatic; drama courses under it, almost visible in GMark: all of Jesus’s miracles in GMark are stageable in a theater. I am not the first modern person to think of GMark as a staged play. In antiquity, theater was the mass entertainment medium. Everyone went to the theater. I am sure that many educated pagans who encountered GMark recognized it was dramatic, and therefore could not be history, with or without miracle stories.

I add that the four gospels, in my opinion, are really low-quality tools on their own if your goal is to recruit nonbelievers. Again, we have to get rid of our (and Litwa’s?) assumption that the four gospels were the first Christian texts educated pagans read. Educated pagans must have known that Christians had other texts, and beliefs supported by authorities outside the gospels. And as time went on, educated pagans knew Christians and could interview them about their beliefs. I think that in general, in all times and places, educated pagans perceived the four-gospel story as myth, illustrative of the larger belief-cloud of the religion (including fulfillment of Scripture). Not a mixture of history and miracles.

I agree with most of what you said, but…

“The uneducated took the stories literally, the educated understood them symbolically.”

This is clearly not the case.

That this is not true is made obvious by the apologists. All of the apologists were very clear that the Gospel accounts were literally true, word for word. This is the case from the second century on down. Those that suggested some kind of allegorical reading were declared heretics and ejected.

Yet the Gospel of Mark drops heavy hints that its narrative is a parable, a symbol. I think it fair to suspect that at least some of the earliest readers and hearers interpreted it symbolically. But that is, granted, an inference, nothing more.

I wrote, “I think that some educated non-Christians (and some Christians) would continue for many centuries to maintain the distinction: The uneducated took the stories literally, the educated understood them symbolically.” To clarify, I meant that even centuries later, SOME educated Christians would have continued to see the gospel stories as symbolic. Some, as you say, were declared heretics and ejected. It’s fair to say that in any religious congregation, there will be a variety of beliefs and understandings. People join or remain members for a variety of reasons. We can’t infer that all members of every congregation, even those pastored by apologists, agreed with everything said from the pulpit. Furthermore, we don’t know how representative of “the average Christian” the apologists were. To me, the fact that they went to the trouble of apologizing shows they were on the defensive, from dissenters without, or maybe even within their congregations.

I agree, there may have been some people who understood Mark’s tale allegorically, but I think we also have to consider that Matthew was by far the more well known and read work. Mark, for the most part, just tagged along. Mark, it seems, was mostly ignored and only barely made it into the Bible. Perhaps some early Pauline initiates understood Mark.

In addition, I suspect if we look at the Derveni Papyrus we may see an example of how Mark may have been intended. The Derveni Papyrus is of course the famous scroll found in a burial mound that describes allegorical interpretation of the Orphic theogonies. According to the writer, most people fail to understand the Orphic works and even the Orphic rites. The writer criticizes the mysteries, or at least the initiates into the mysteries, because they fail to learn the secrets. They fail to learn the secrets because they don’t study the text. The failure to study the texts results from the failure to recognize their allegory and symbolism. The Orphic texts, we are told, are all encoded in enigmas and only those with ears to hear can truly understand them. Orpheus intentionally speaks in riddles so that only those devoted to the study of the texts can comprehend them. The writer tells us of ways to decode the Orphic texts to learn the mysteries.

If we concede that Paul was engaged in mystery religion, and that Mark is following Paul, then Mark is writing an allegorical mystery narrative. I explore this further in my book.

Whoops, this was supposed to be in reply to Neil.

@RGPRICE “If we concede that Paul was engaged in mystery religion and that Mark is following Paul, then Mark is writing an allegorical mystery narrative.” This is what it was taught in my time studying hermeticism following the path of the Golden Dawn.

In our work, the 7 principles were taught using the Mark. I have never seen anything published on that. Does it makes sense to you? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kybalion#The_seven_Principles

Let’s not confuse two different questions. We have no clear evidence to enable us to pin down the origins of either gospel. We can’t even definitely say when either was composed (the possible range covers a period between 70 and 170) or by whom or for whom or where . . .

By the time we come to unequivocal independent evidence we are looking at a quite different question: how to understand the acceptance (and interpretations) of these works by the “proto-catholic” branch of christianity.