From Thomas Ferguson, Paul Jorgensen and Jie Chen:

As our Table 4 above showed [not shown here], Trump had largely financed his primary campaign with small contributions and loans from himself. As late as mid-May, he remained convinced that his success in using free media and his practice of going over the head of the establishment press directly to voters via Twitter would make it unnecessary for him to raise the “$1 billion to $2 billion that modern presidential campaigns were thought to require” (Green, 2017).

As the convention approached, however, the reality of the crucial role of major investments in political parties started to sink in. Some of the pressure came from the Republican National Committee and related party committees. Their leaders intuitively grasped the point we demonstrated in a recent paper: that outcomes of most congressional election races in every year for which we have the requisite data are direct (“linear”) functions of money (Ferguson et al., 2016). The officials could safely project that the pattern would hold once again in the 2016 Congressional elections (as it did – see Figure 3).56 But the Trump campaign, too, began to hold out the tin cup on its own behalf with increasing vehemence. As we noted earlier, small donations had been flowing steadily into its coffers. Unlike most previous Republican efforts, these added up to some serious money. But in the summer it became plain that the sums arriving were not nearly enough. In many senses, Trump was no Bernie Sanders.

. . . . .

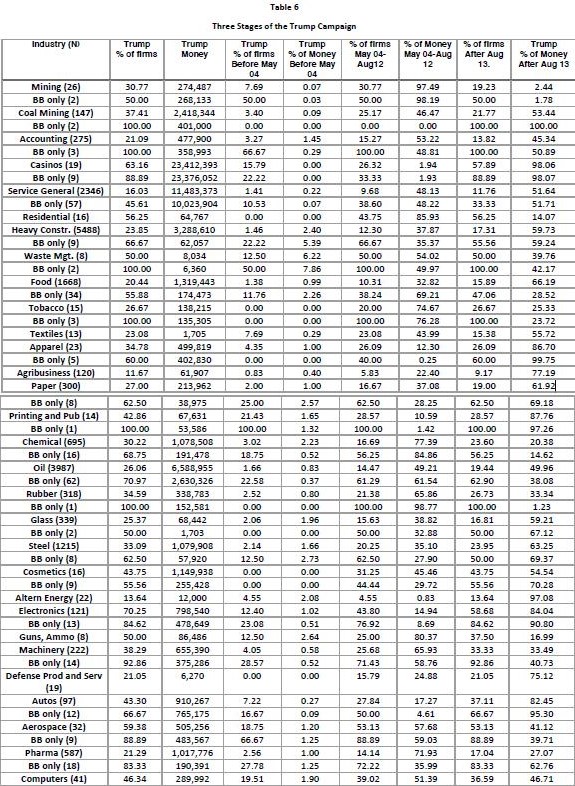

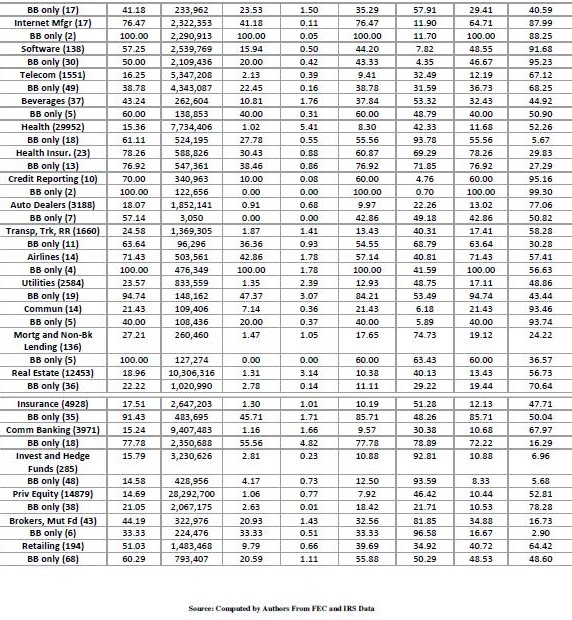

We are able to source the revenues to individual big businesses and investors and aggregate them by sector (Table 6) and also by specific time intervals. Our data reveal aspects of the campaign’s trajectory that have received almost no attention. It is apparent that Trump’s and Manafort’s efforts to conciliate the Republican establishment initially met with some real success. The run up to the Convention brought in substantial new money, including, for the first time, significant contributions from big business. Mining, especially coal mining; Big Pharma (which was certainly worried by tough talk from the Democrats, including Hillary Clinton, about regulating drug prices); tobacco, chemical companies, and oil (including substantial sums from executives at Chevron, Exxon, and many medium sized firms); and telecommunications (notably AT&T, which had a major merge merger pending) all weighed in.57

Money from executives at the big banks also began streaming in, including Bank of America, J. P. Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, and Wells Fargo. Parts of Silicon Valley also started coming in from the cold. Contrary to many post-election press accounts, in the end contributions from major Silicon Valley firms or their executives would rank among Trump’s bigger sources of funds, though as a group in the aggregate Silicon Valley tilted heavily in favor of Clinton. Just ahead of the Republican convention, for example, at a moment when such donations were hotly debated, Facebook contributed $900,000 to the Cleveland Host Committee. In a harbinger of things to come, additional money came from firms and industries that appear to have been attracted by Trump’s talk of tariffs, including steel and companies making machinery of various types (Table 6).58 The Trump campaign also appears to have struck some kind of arrangement with the Sinclair Broadcast Group, which owns more local TV stations than any other media concern in the country, for special access “in exchange for broadcasting Trump interviews without commentary (Anne, 2017).”

Crisis

Crisis

In mid-August, as Trump sank lower in the polls, the crisis came to a head. Rebekah Mercer had her fateful conversation with Trump at a fundraiser. Manafort, already under pressure from a string of reports about his ties with the Ukraine and Russia, was first demoted and then fired. Steve Bannon took over direction of the campaign and Kellyanne Conway was promoted to campaign manager (Green, 2017). . . . .

Breaking Through

But within hours after Bannon and Conway took over, press accounts reported that “Bannon and Conway have decided to target five states and want to devote the campaign’s time and resources to those contests: Florida, North Carolina, Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania. It is in those states where they believe Trump’s appeal to working-class and economically frustrated voters has the best chance to resonate.” (Costa et al., 2016). Their strategy clearly evolved to embrace a few other states, but this retargeting had a vital counterpart on the financial side.

The focus on the old industrial states attracted more money from firms in steel, rubber, machinery, and other industries whose impulses to protection figured to benefit from this focus. But the bigger story over the next few weeks was the vast wave of new money that flowed into the campaign from some of America’s biggest businesses and most famous investors. Sheldon Adelson and many others in the casino industry delivered in grand style for its old colleague. Adelson now delivered more than $11 million in his own name, while his wife and other employees of his Las Vegas Sands casino gave another $20 million. Peter Theil contributed more than a million dollars, while large sums also rolled in from other parts of Silicon Valley, including almost two million dollars from executives at Microsoft and just over two million from executives at Cisco Systems.

A wave of new money swept in from large private equity firms, the part of Wall Street which had long championed hostile takeovers as a way of disciplining what they mocked as bloated and inefficient “big business.” Virtual pariahs to main-line firms in the Business Roundtable and the rest of Wall Street, some of these figures had actually gotten their start working with Drexel Burnham Lambert and that firm’s dominant partner, Michael Milkin. Among those were Nelson Peltz and Carl Icahn (who had both contributed to Trump before, but now made much bigger new contributions). In the end, along with oil, chemicals, mining and a handful of other industries, large private equity firms would become one of the few segments of American business – and the only part of Wall Street – where support for Trump was truly heavy.59

In the final weeks of the campaign, a giant wave of dark money flowed into the campaign. Because it was dark the identity of the donors is shrouded. But our scrutiny of past cases where court litigation brought to light the true contributors suggests that most of this money probably came from the same types of firms that show up in the published listings. In our data, the sudden influx of money from private equity and hedge funds clearly began with the Convention but turned into a torrent only after Bannon and Conway took over. We are interested to see that after the election some famous private equity managers who do not appear in the visible roster of campaign donors showed up prominently around the President. An educated guess on the sources of some of that mighty wave is thus not difficult to make, though the timing of the inflow from the big private equity firms by itself is suggestive. In the end, total spending on behalf of Trump from all sources totaled slightly more than $861 million – within reasonable hailing distance of the Clinton campaign’s $1.4 billion (including Super Pacs, etc.), especially considering how late serious fundraising efforts started.

(Ferguson, Jorgensen, Chen, pp. 42-45)

Ferguson, Thomas, Paul Jorgensen, and Jie Chen. 2018. “Industrial Structure and Party Competition in an Age of Hunger Games: Donald Trump and the 2016 Presidential Election.” Institute for New Economic Thinking, Working Paper No. 66, January. https://www.ineteconomics.org/research/research-papers/industrial-structure-and-party-competition-in-an-age-of-hunger-games.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!