Nathan recently chastised me:

Why the double standard, Neil?

Barely a month ago you were empathizing with the Japanese by laying blame on the U.S. for Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, noting that “the U.S. had just cut off 80% of Japan’s oil supply so [Japan] was obviously faced with a situation of complete capitulation or war with the U.S.”

Yet now, rather than empathize with Israel as well, you seem to lay the blame on them for the Six-Day War when you talk of the “myth of 1967 being the war when the Arabs attacked Israel,” and then refer to “the territory from which Israel launched its attack on the Arabs.”

Why not mention that the Soviet’s and Syria were spurring an Arab attack by incorrectly reporting Israel had plans to invade Syria? Why not mention that Nasser had asked and been granted his request to have UN peace-keeping forces removed from the Sinai Peninsula, and then had begun amassing Egyptian troops in the Sinai? Why not mention that Nasser was blockading Israeli ships in the Straits of Tiran? Why not mention that Jordan’s King Husayn had flown to Cairo to sign a defense pact with Egypt? In other words, Neil, why not mention the fact that, like Japan, Israel itself was faced with a situation of war? (Yes, Neil, these questions are rhetorical. Given your obvious agenda, it’s quite clear why you wouldn’t mention these things.)

I promised Nathan a response in a full post. So here we go.

Let’s take these points one by one:

- Why not mention that the Soviet’s and Syria were spurring an Arab attack by incorrectly reporting Israel had plans to invade Syria?

I did. I wrote two days after the post about Japan the following about the 1967 War:

The Soviet Union, supporter of the Syrian government, in response sent a report to Syria’s ally Egypt to warn that Israel was moving its forces towards the northern border and planning to attack Syria. Egypt’s president, Nasser, was pressured to take some decisive action to maintain his credibility as leader of the Arab nations:

The report [from the USSR] was untrue and Nasser knew that it was untrue, but he was in a quandary. His army was bogged down in an inconclusive war in Yemen, and he knew that Israel was militarily stronger than all the Arab confrontation states taken together. Yet, politically, he could not afford to remain inactive, because his leadership of the Arab world was being challenged. . . . Syria had a defense pact with Egypt that compelled it to go to Syria’s aid in the event of an Israeli attack. Clearly, Nasser had to do something, both to preserve his own credibility as an ally and to restrain the hotheads in Damascus. There is general agreement among commentators that Nasser neither wanted nor planned to go to war with Israel. (252f)

Nasser decided on three-fold action to impress the Arab public . . . .

…

- Why not mention that Nasser had asked and been granted his request to have UN peace-keeping forces removed from the Sinai Peninsula, and then had begun amassing Egyptian troops in the Sinai?

I did. I wrote in the same post (within two days of my Japan post):

Nasser decided on three-fold action to impress the Arab public:

1. He sent a large force into the Sinai

2. He ordered the removal of the U.N. peacekeepers from the Sinai

…

- Why not mention that Nasser was blockading Israeli ships in the Straits of Tiran?

I did. That was the third point in the above list.

3. He closed the Straits of Tiran to Israel shipping

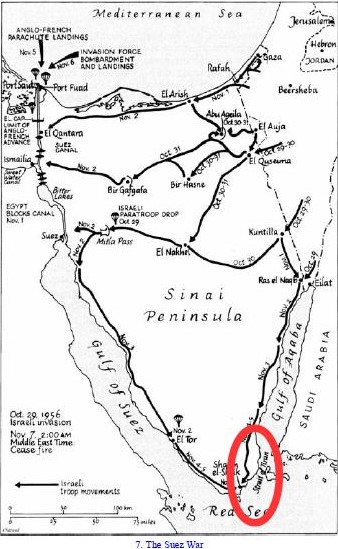

I even added a graphic to that same point:

…

- Why not mention that Jordan’s King Husayn had flown to Cairo to sign a defense pact with Egypt?

You caught me out on that one. But can you explain how a “defense pact” is evidence for a plot to wage a non-defensive war of aggression? Till then, I think you should take note of what I did post about Jordan and King Hussein:

The fighting on the eastern front was initiated by Jordan, not by Israel. King Hussein got carried along by the powerful current of Arab nationalism. . . . On 5 June, Jordan started shelling the Israeli side in Jerusalem. This could have been interpreted either as a salvo to uphold Jordanian honor or as a declaration of war. Eshkol decided to give King Hussein the benefit of the doubt. Through General Odd Bull, the Norwegian chief of staff of UNTSO, he sent the following message on the morning of 5 June: “We shall not initiate any action whatsoever against Jordan. However, should Jordan open hostilities, we shall react with all our might, and the king will have to bear the full responsibility for the consequences.” King Hussein told General Bull that it was too late; the die was cast. Hussein had already handed over command of his forces to an Egyptian general. He made the mistake of his life. Under Egyptian command the Jordanian forces intensified the shelling, captured Government House, where UNTSO had its headquarters, and started moving their tanks into the West Bank. (260)

…

- Given your obvious agenda, it’s quite clear why you wouldn’t mention these things.

Well, since you can now see that I had indeed mentioned almost all of those things you said that I “would not mention”, has your view of “my agenda” changed in any way?

Before replying I suggest you read that post and in particular the General Dayan’s admissions about responsibility for the war.

Meanwhile, in the words of Prime Minister Begin in 1982:

In June 1967 we again had a choice. The Egyptian army concentrations in the Sinai approaches do not prove that Nasser was really about to attack us. We must be honest with ourselves. We decided to attack him.

This was a war of self-defence in the noblest sense of the term. The government of national unity then established decided unanimously: We will take the initiative and attack the enemy, drive him back, and thus assure the security of Israel and the future of the nation.

We did not do this for lack of an alternative. We could have gone on waiting. We could have sent the army home. Who knows if there would have been an attack against us? There is no proof of it. There are several arguments to the contrary. While it is indeed true that the closing of the Straits of Tiran was an act of aggression, a causus belli, there is always room for a great deal of consideration as to whether it is necessary to make a causus into a bellum.

General Matityahu Peled in Haaretz (March 19, 1972).

The thesis that the danger of genocide was hanging over us in June 1967, and that Israel was fighting for its physical existence is only a bluff which was born and developed after the war.

Cooley, John K. 1973. Green March, Black September: The Story of the Palestinian Arabs. London ; New York: Routledge. pp. 161-163:

In the West and in Israel, a widely-accepted theory is that the Arab states, possibly with Soviet help, planned Israel’s extermination in June I967. These plans necessitated Israeli pre-emptive action. But this thesis received a rude jolt inside Israel itself in I972 with the outbreak of a public debate, scarcely reported at all in the British and American press, among high-ranking Israeli army veterans of the I967 war.

It all began, as reported in Haaretz of March I3, I972, with the fiat assertion of Reserve General Matityahu Peled that ‘the claim that Israel was under the menace of destruction is a “bluff.” ‘ Dr. Peled, a lecturer on Middle East history at the University of Tel Aviv, spoke in a public discussion on Amos Elan’s book, The Israelis, Founders and Sons. Dr. Peled contended that Elan, despite his unorthodox approach to some of the popular myths about Israel, had uncritically accepted some axioms which were not true.

In June I967, said Dr. Peled, Israelis were threatened with destruction “neither as individuals nor as a nation . . . the Egyptians concentrated 8o,ooo soldiers in Sinai, and we mobilized hundreds of thousands of men against them.” This made the Israeli Government’s task of explaining the war more difficult, Dr. Peled asserted, because it had been generally accepted that Israel should not wage war for political purposes, but only if by remaining passive or on the defensive, it faced extermination. Dr. Peled maintained that the war was caused by the Soviet Union’s attempts to change the region’s power balance in its own favour and to replace the ‘American settlement’ reached in I957 after the Suez War with a Soviet one. The Arabs had a secondary role, and had not been in any position to destroy Israel since 1948.

Before the uproar over these heterodox statements had died down, they were echoed from a singularly different quarter: former General Ezer Weizman, who had commanded the Israel Air Force for many years before his recent entry into politics and who is unanimously regarded by his countrymen as a leading hawk. In a lecture reported in Haaretz of March 20, 1972, General Weizman said he would “accept the claim that there was no threat of destruction against the existence of the State of Israel. This does not mean, however, that one could have refrained from attacking the Egyptians, the Jordanians and the Syrians. Had we not done that, the State of Israel would have ceased to exist according to the scale, spirit and quality she now embodies.”

General Weizman expanded on these views, contested by many Israelis who insisted there was indeed a threat of physical liquidation by the Arabs, in an article published in Haaretz on March 29, 1972:

A state does not go to war only when the immediate threat of destruction is hanging over its head … The threat of destruction was already removed from Israel during the War of independence …

The question asked now is whether there was a danger of destruction in the State of Israel on the eve of the Six Day War, or not. There is no doubt that the Arabs threatened us with destruction, because they wished it then, and maybe this is still their wish. The heart of the question, however, is aimed at our estimation of the Arabs’ capacity to destroy us.

Had the Egyptians attacked first, they would have also then suffered a complete defeat, in my opinion. The only difference is that the war then would have been prolonged; to command control of the air, maybe thirteen hours would have been needed instead of only three . . . On the Eastern front, it was Jordan who first opened fire. Despite this we conquered the West Bank swiftly. It is a historical fact that we moved up the Golan heights only on the morning of June 9 and, this too, after much disputation. If indeed the Syrian enemy threatened to destroy us, why did we wait three days before we attacked it?

We entered the Six-Day War in order to secure a position in which we can manage our lives here according to our wishes without external pressures . . . From the long-range historical view, the Six-Day War was a direct continuation of the War of Independence. After the stage of “preventing destruction”, which was completed between the first and second truces, the natural objective of the war became — whether the then leadership was conscious of this or not — the creation of a situation in which Israel could apply most of its efforts and resources to realize the Zionist objectives … not that we initiated the Six Day War; we certainly did not cause it. But since it was imposed on us, our national instincts led us to take advantage of it beyond the immediate military and political problems it came to answer. In other words, the objectives of the war changed and expanded through the process of fighting, short as it was.

All these Israeli statements, concerning the Russians, Syria and the real causes and objectives of the Six-Day War, give a rather different view from the popular Israelo-Western idea, and, for that matter, the popular Arab one. The classic Israelo-Western view, developed by commentators, is that the sequence was roughly this: Israeli reprisals against fedayeen attacks from Syria, restrained as they were, led to more Syrian warmongering; next, Syrian and Soviet intelligence fed President Nasser with false reports of an Israeli build-up against Syria and of aggressive Israeli intentions which did not exist; Nasser then mobilized under his treaty obligations with Syria and ‘closed’ the Straits of Tiran after expelling the United Nations shield from Gaza and Sinai; Israeli forces then moved on June 5 only because of an imminent Egyptian threat of attack (though we now know that President Nasser heeded both Soviet and US warnings not to attack first, while warning his High Command of the probability of a surprise Israeli attack). The classic Arab and Soviet view of the war’s causes, also at least partly controverted by the Israeli statements we have seen, was roughly that Israel conspired with its Western supporters, especially the United States, to attack the Arabs, seize and colonize new territories from them (which latter it did do) and force them to install new governments which would have to accept an Israeli diktat of peace on Israeli terms (which it did not, or could not, do). The Israeli statements over the war’s origins, therefore, suggest that the truth lay in fact somewhere between the extremes of the two popular myths.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“have UN peace-keeping forces removed from the Sinai Peninsula”

Note that Israel refused to have any UN peace-keeping forces on the Israel side of the line.

Indeed. That detail alone belies the claim Israeli authorities genuinely believed they were faced with imminent annihilation.

Hi Neil,

Since you referenced Gen. Peled, are you familiar with his son, Miko? In particular, his book, The General’s Son?

Richard G.

No, I was not aware of Miko or his book. But both look very interesting from the Wikipedia launch pad. Thanks for the notice.

Incidentally, Neil, I noticed you didn’t mention this:

“I know how at least 80 percent of the clashes there started. In my opinion, more than 80 percent, but let’s talk about 80 percent. It went this way: We would send a tractor to plough someplace where it wasn’t possible to do anything, in the demilitarized area, and knew in advance that the Syrians would start to shoot. If they didn’t shoot, we would tell the tractor to advance farther, until in the end the Syrians would get annoyed and shoot. And then we would use artillery and later the air force also, and that’s how it was.”

— Moshe Dayan, Israel’s former Minister of Defence, describing how to provoke a military incident on the Golan Heights. From a 1976 interview with Yediot Ahronot newspaper, given on condition that it not be published till after his death. Cited in Ari Shavit’s The Iron Wall, p.236-237.

Tut tut.

I do believe that was mentioned in my initial post.