[Daniel] Ellsberg was called The Most Dangerous Man in America by President Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger. Now Ellsberg, an articulate and energetic seventy-nine years old, was passing on the baton to Assange—and going one step further. He agreed that Assange was a ‘good candidate for being the most dangerous man in the world’ and he should be ‘quite proud of that’. He also had some advice for Assange. He was ‘not safe physically wherever he is’. —

About two days ago I watched this press conference. The editor-in-chief sums up the fundamentals of journalism in a democratic society: If it’s newsworthy, if it’s in the public interest, and if it’s true — it should be published.

So many of knew Julian Assange’s days in the Ecuadorian embassy were imminently threatened but was not expecting the arrest so soon.

I know many readers of this blog have no time for Assange. I cannot deny I find his narcissism very unlikeable. But that’s not the point, of course. (And yes, I know the reasons others loathe him go well beyond his personality.)

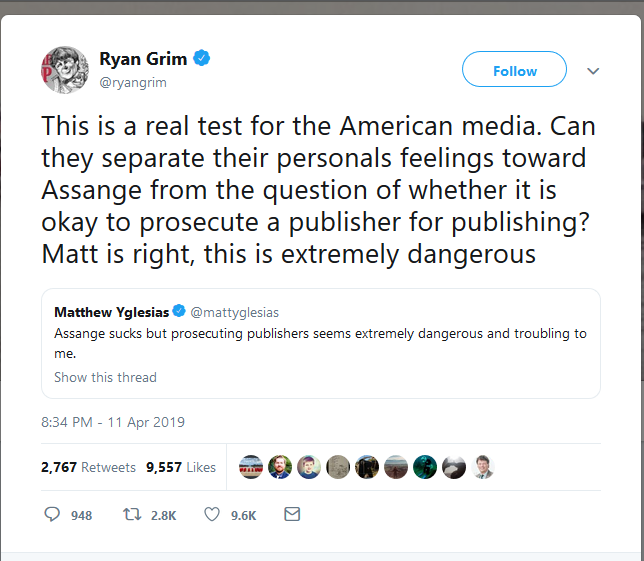

A Real Test

-o0o-

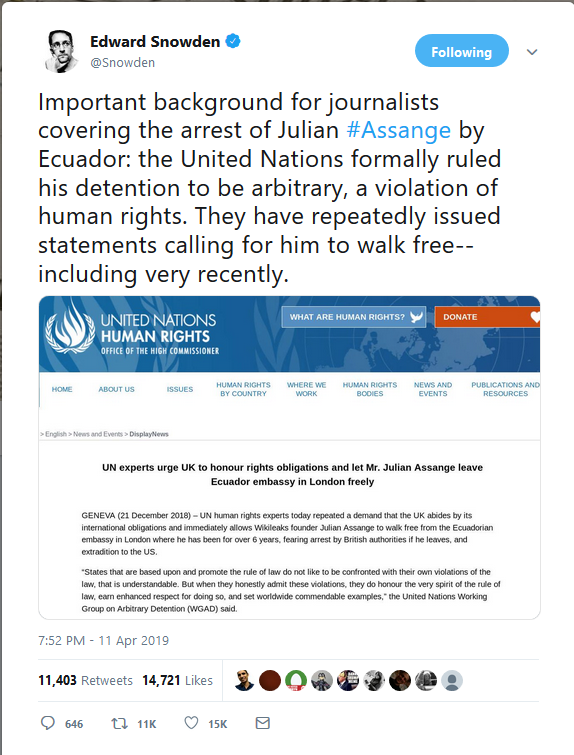

Important Background

-o0o-

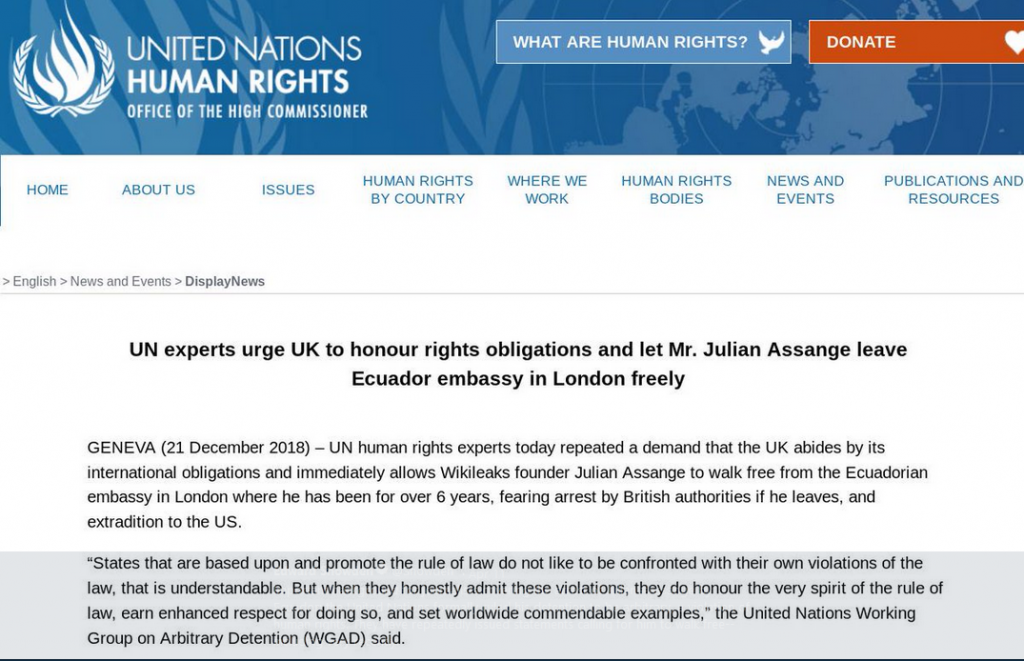

The excerpt of the UNHR document in easier to read size:

The full document is at https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24042&LangID=E

-o0o-

Good Bullshit-free Analysis and Summary

….

-o0o-

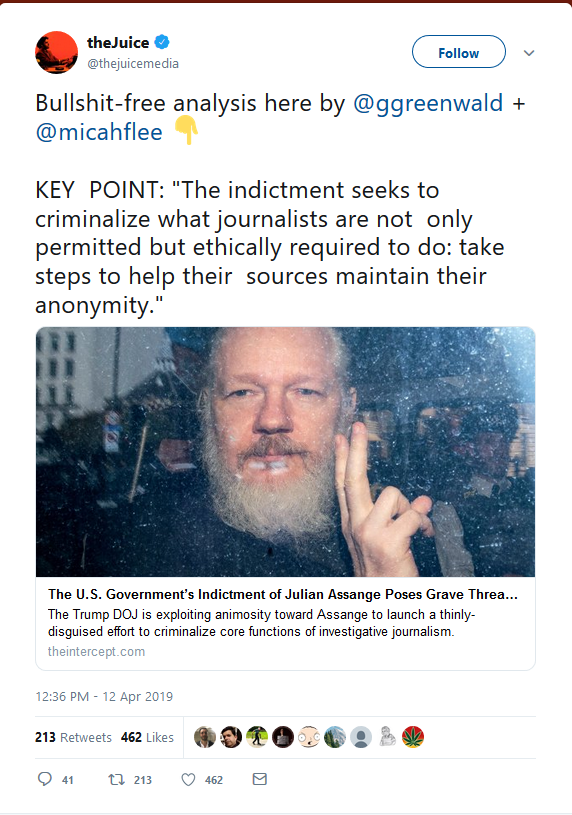

Link to that Good Summary of What Just Happened / “Bullshit-free Analysis”:

Greenwald, Glenn, and Micah Lee. 2019. “The U.S. Government’s Indictment of Julian Assange Poses Grave Threats to Press Freedoms.” The Intercept (blog). April 12, 2019. https://theintercept.com/2019/04/11/the-u-s-governments-indictment-of-julian-assange-poses-grave-threats-to-press-freedoms/.

-o0o-

Criminalizing Journalism

-o0o-

Exposing Evidence

-o0o-

Assange’s Australian Lawyer Comments

-o0o-

The Video Clip

-o0o-

And finally, a pdf file of the seven page U.S. indictment:

-o0o-

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Looks like the U.S. govt will have to prove that Assange had reason to believe the leak would be advantageous to a foreign govt. (Indictment & U.S. Code provision).

Assange is a publisher, like Katharine Graham who published the Pentagon Papers. A couple of years ago a film was made of the affair with Meryl Streep playing the hero who took the risk of defying the government by exposing its unsavory secrets.

Maybe in 30 or 40 years Assange will be seen as the hero in this story…

An outstanding perspective. Thank you.

I am a long-term follower of this wonderful website, but I usually don’t feel myself qualified to comment on most of the issues discussed here.

In this specific case, I have to say that other viewpoints are available. Assange and Wikileaks may have done some service in revealing the extent to which US forces in Afghanistan overstepped the boundaries of legitimate action in wartime. But they then went on to release a whole shedload of diplomatic and other material that its authors and recipients had every right to consider as confidential, and which could be calculated to do damage or worse to the Governments concerned.

Assange and his colleagues assert that none of this stuff should be confidential in the first place. If that principle was followed through across the board, diplomacy would in effect become impossible. But of course he and his acolytes are not consistent: they have never bothered to reveal anything about the diplomatic or military communications of Russia or China, to name just a couple of examples. Maybe they can’t find anything. Maybe they haven’t tried. Maybe they have been encouraged not to try.

Not being qualified to discuss matters, for better or worse certainly hasn’t held me back too much.

There are multiple questions.

One is whether it is in fact true that Wikileaks (WL) published nothing from Russia. I have read responses to this sort of criticism that it in fact has, but I don’t know. There are similar criticisms about WL’s not having published anything against Israel, though I have also read that it has published US correspondence about Israel that could be embarrassing for Israel. Some go so far as to assert that Assange must therefore be a Mossad operative. However I have read that it has published US correspondence about Israel that could embarrass Israel’s government. Not knowing what has been submitted to WL, I personally have no knowledge of what they have that hasn’t been published, whether it includes a lot from Russia and China–or Israel, I don’t know. I may be wrong, but my impression that they have solicited material from everywhere, though like you I don’t know how hard they have tried.

WL have set forth material where civilians are killed and, according to some, in a methodical and malicious fashion. I have personally examined little of the material. Questions arise. We can think of governments and militaries of the past who have done so much cold-blooded killing of civilians (“war crimes”) that according to international law, I am given to understand, it is one’s requirement to resist and complain as publicly as possible even at the risk of being imprisoned or killed. In such cases many people would not think highly about claims to secrecy and confidentiality. On the other hand, others assert that killing lots of civilians always happens in war, and that some wars are good, also that some governments are so good that they can appropriately withhold significant disturbing material from their subjects. What does one think of killing civilians and in what situations? Is one’s government and military of a different sort than some of the blatantly horrible ones of the past, or is one living in a bubble in believing them to be especially different? When does it need to be made public and under what conditions (for example, does one publish information about a particularly unnecessary massacre if a secret operative’s cover might be blown)? etc etc etc.

There are many questions. Scrutiny from different perspectives, including even unusual ones, may be helpful.

Hi Steve and thanks for the comment. One reason I have not posted here for the last day or two is because I have withdrawn to finish reading/re-reading a couple of serious studies on WikiLeaks and Assange up to 2010/2011. You will be interested in the following comments in relation to your concerns —

In discussions with WikiLeaks and other major newspapers as they prepared to release the diplomatic cables the media was careful to be sure that no innocent persons were put at risk and they also considered the arguments put out by governments trying to persuade them not to publish:

The previous chapter describes in detail the many, many hours invested in carefully reading through documents before their release and removing names that woud possibly be put at risk.

Contrary to what WikiLeaks was accused of doing there was no mass dump of hundreds of thousands of cables and what was released was carefully redacted beforehand to protect persons who would otherwise be endangered.

Contrary to many accusations at the time the leaks probably did far more damage to Russia than the United States.

There are pages detailing the evidence released in the documents for Russia security and intelligence services being in charge of mafia gangs operating not only in Russia but throughout Europe.

There is no evidence for the major damage supposedly caused by the release of the documents:

Fowler, Andrew John. 2011. The Most Dangerous Man in the World: The Inside Story on Julian Assange and the WikiLeaks Secrets. Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Press.

Leigh, David, and Luke Harding. 2011. Wikileaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy. London: Guardian Books.

This looks like an appropriate moment to comment on Jim West’s bent comment on Assange (I’d try to point out to Jim his failure to do due diligence in checking his sources before posting but each time I have posted to him before he ignores me or posts on his blog a straight out lie about what I wrote.)

He wrote at https://zwingliusredivivus.wordpress.com/2019/04/11/julian-assange-is-putins-lapdog/

That quote comes from Leigh and Harding. Here is that passage in context. It opens with a quote from Declan Walsh, the Guardian‘s Pakistan-based correspondent:

As for being a Russian lapdog, my previous comment quoted enough to demonstrate that WikiLeaks published far more damaging material about Russia than it did about America. I don’t expect Jim to change his mind or apologize, though.

Noteworthy how this posting on Assange follows “All the Way”.

I wonder whether this topic is has made it much into the public discussions in Australia, whether, for example, candidates in the election have commented on it.

My understanding, from the publisher’s comments at Talking Points Memo, is that there is a bright-line distinction between what’s permissible and what’s not. It’s based on a very simple criterion: who initiated the disclosure. The first disclosure from Chelsea Manning to Wikileaks falls squarely on the protected side: Wikileaks had nothing to do with what she did – that was solely her action. To use the example from TPM: it dropped into their laps from the sky. Once they started helping her and asking her to make more disclosures, though, it equally clearly falls on the other side. This is apparently long-standing and settled law in the US; it’s not a case where the Trump administration is trying to stifle the press.

I don’t find arguing from a position of moral outrage to be particularly productive; the jury will decide whether there is enough evidence to convict, and again from the TPM analysis, the maximum sentence is apparently 5 years, not life.

What is settled law is not the full issue here. Daniel Ellsberg, one of the heroes of our time, violated settled law in releasing the Pentagon Papers, and has told of being prepared to spend a long prison term as the likely consequence for his action. In Ellsberg’s case, the charges against him were thrown out on a procedural technicality by a judge and he was not convicted, but it could easily have gone the other way. Similarly, Vanunu of Israel and many others. Public opinion matters in cases such as this. There is a rich and honorable tradition in America of civil disobedience in which sometimes the moral thing to do is wilful violation of settled law, the right thing for the public to do is support it, and the right thing for juries to do is refuse to convict even in the face of unequivocal evidence of illegality.

You’re drawing the wrong parallel from history.

Manning was Ellsberg. Assange/Wikileaks was the NY Times.

Manning did go to jail.

If all Assange/Wikileaks did was what the NY Times did, there should be no criminal liability.

Assange’s defenders spend a lot of time on allegations in the indictment that merely provide context but that are not an element of the charged offense. As a lawyer, Glenn Greenwald knows better, which makes his tweet extremely disingenuous.

Simply put, Assange is charged with a conspiracy to hack a government computer. The facts as alleged indicate that the conspiracy resulted in a failed attempt to hack that yielded no additional information.

In his article, Glenn argues that “two facts in particular have been utterly distorted by the DOJ and then misreported by numerous media organizations.”

Glenn’s first fact, that the “key allegation” is not new is irrelevant. Yes, the Obama administration exercised its prosecutorial discretion and chose not to seek an indictment of Assange for trying to help crack a password, but that exercise did not and does not preclude the Trump administration from taking a different approach.

Glenn’s second “fact” is a howler that is flatly rebutted by paragraph 9 of the indictment. The password Assange allegedly attempted to help in cracking was the administrator’s password, i.e., the password of a super-user with greater access privileges than Manning enjoyed. Seriously. The DOJ says it right there in paragraph 9. Glenn just makes stuff up.

To be clear, while I don’t care about Assange one way or another, I do care about protecting free speech and a free press. As a lawyer, I likely would have let the Obama administration’s decision no to pursue and indictment here stand because there is a big difference between charging somebody and convicting them, but that’s a judgment call, and seeking an indictment was within the realm of reason.

I have grown weary and wary of Glenn’s work these days because it is often intentionally misleading. As soon as he speaks up, I fact check him and usually find he is saying misleading things, if not outright lies.

It is good to focus on facts. I personally have come to the conclusion that I need to be skeptical of any source. I therefore try to go to disparate sources, hoping to gain some sense that might be approximately correct. I can honestly right that I would not be astonished if my current impression on this and other matters turn out to be badly wrong.

It is good that you noted that there may well have been a violation of law, despite the clamor that the matter is one only of free speech and freedom of the press.

Nevertheless, I believe that there are a couple of things that are more important than the law, as important as it is: facts, and what is right.

First, the facts, and not just of whether law was violated. There is considerable muddle about what happened in general with various hacks or leaks, for example. People of different opinions have axes to grind; many write confusingly; others with potentially useful knowledge may in theory be under gag orders or may otherwise have reason not to want to stick their necks out.

Second, even more important is what is right. Slavery was legal at one point in the US. In fact, if I recall my history correctly, it was a felony to help an escaped slave, according to law tested in courts with legal propriety. Later racial segregation was legal, and after full and apparently legally proper judicial review.

Another problem with focusing on law more than on the constellation of facts or on ethics is the matter of selective prosecution. At least in some US jurisdictions, at least in some eras, for example, it has been or was common for governmental officials to arrest, prosecute, and punish blacks disproportionately for offenses for which whites were typically not arrested. Perhaps those who might embarrass the powers that be were at special risk for stringent prosecution in grey zone areas for severer charges, as well as annoying, even torturous or lethal extrajudicial treatment by officials deriving great power from their positions and their connections, including with the established press. Meanwhile whites with connections, such as those who might be embarrassed by any questioning the Jim Crow system, literally were able to get away with murder.

I do not mean to imply that prosecuted or persecuted blacks were always innocent, or that the persecuted never ever violated the law or ethics. Moreover a variety of really bad actors over the years have undoubtedly improperly claimed to be victims of persecution in order to get away with having done all sorts of bad stuff.

There are many, many, many laws and as you suggest sometimes there are prosecutions and sometimes not. Very hard to figure out.

Hi Scot,

You said:

“Glenn’s second “fact” is a howler that is flatly rebutted by paragraph 9 of the indictment. The password Assange allegedly attempted to help in cracking was the administrator’s password, i.e., the password of a super-user with greater access privileges than Manning enjoyed. Seriously. The DOJ says it right there in paragraph 9. Glenn just makes stuff up.”

However, in the Intercept article, Greenwald/Lee state:

“Each account is protected by a password, and Windows computers store a file that contains a list of usernames and password “hashes,” or scrambled versions of the passwords. Only accounts designated as “administrator,” a designation Manning’s account lacked, have permission to access this file.”

I’m not sure what you mean by “Glenn just makes stuff up”. Yes, it’s a bit of a catch 22, for in order to use another person’s username, Manning (allegedly) needed to access the hashes which was only possible via the administrator’s info. But Greenwald/Lee did mention this in the article.

Richard G.

Publisher or Source? — A Debated Question

. . . .

. . . .

Fowler, Andrew. 2011. The Most Dangerous Man in the World: The Explosive True Story of Julian Assange and the Lies, Cover-Ups and Conspiracies He Exposed. Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Press.

The issue of whether Assange is a journalist or not (he is) seems irrelevant. There is no journalist’s privilege to commit crimes or attempt to commit crimes. Remember when News Ltd hacked celebrities phones, i.e. committed crimes, to get good stories which their readers loved? It would have been just as bad if News Ltd encouraged others to hack those phones for them and, as an inducement, promised not to reveal the names of those who did the hacking for them. No one would claim that Assange can’t be charged with rape (or something similar) in Sweden “because he is a journalist trying to get a story”. Naturally Assange will not be charged in the US with publishing something, but with a clearly defined crime.

One could argue that governments concoct false or weak charges of criminal activity to intimidate journalists they don’t like, but that is a different issue, which has to be addressed by showing the crime has not been proved, or convincing the British authorities that the US charges have an illegitimate purpose, and extradition should not be granted.

I assume first Assange has to face some skipping bail charges in the UK (again, an ordinary criminal charge, against which a journalist has no special immunity).

Publisher or Source? — The Debate, continued

Leigh, David, and Luke Harding. 2011. Wikileaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy. London: Guardian Books.

Hi Neil,

Yesterday, Chris Hedges, on his TV show, On Contact, interviewed Vijay Prashad regarding the Assange arrest. I couldn’t find it on youtube, but here it is from RT’s website:

https://www.rt.com/shows/on-contact/456464-assange-arrest-extradition-prashad/

Richard G.

Thank you to all who contributed to this rich and vital discussion. The law is an ass. Those in power exploit it to their advantage. Julian has embarrassed them and they have sought to punish and shut him up and thereby set a precedent and warning to other whistle-blowers and journalists. It’s up to us in Australia now to keep contacting our members of parliament to demand that our government take steps to bring Julian home and rethink our foreign policy and distance itself from the US, recognising that those who control the US government and it’s military-industrial complex are the bully that is provoking non-Christian religious people such as Islamic extremists to actually be more aggressive against Australia ! We need a song, and I had better write it – “Middle Class Get of Your Arse”.