For an annotated list of previous posts in this series see the archived page:

Daniel Gullotta’s Review of Richard Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus

We finally arrive at the double-back-flip as Daniel Gullotta’s concluding word on his discussion of how wrong he believes it is to place Jesus in a Rank-Raglan scale.

Even if Jesus’ life merited a 20 out of 22 on the Rank-Raglan hero-type list (which it does not, as I have shown), this does not confirm his place amongst other mythological figures of antiquity. As the late folklorist Alan Dundes* pointed out, mythicists’ employment of this analysis does not have much to do with whether Jesus existed; it is merely an exercise in literary and psychoanalytic comparisons.124 The traditions of Jesus conforming to these legendary patterns does not negate his historicity any more than the legends connected with Alexander the Great, Augustus Caesar, and Apollonius of Tyana denies theirs.

(Gullotta, p. 344 — * Dundes, as we saw in the previous post, argues that Jesus certainly fits 17 of Raglan’s 22 points)

And here we will address what I offered two posts ago: a discussion of the rationale or place of the archetypes in any discussion of the historicity of Jesus.

After having gone to such lengths to persuade readers that the use of the Rank-Raglan archetypes was an intellectually dishonest ploy by Carrier, that the archetypes did not fit Jesus anyway, Gullotta concludes all of that by agreeing with what Carrier said in the very first place when pointing out that they do not prove the historicity or nonhistoricity of Jesus! The problem with Gullotta’s conclusion, however, is that he in fact repeats what Carrier himself said without realizing he could have quoted Carrier to make his point (supposedly) against Carrier! Carrier writes at length about how historical persons do indeed fit elements in the Raglan list and accordingly argues a fortiori.

[I]f a real person can have the same elements associated with him, and in particular so many elements (and for this purpose it doesn’t matter whether they actually occurred), then there should be many real persons on the list—as surely there are far more real persons than mythical ones.

Therefore, whether fitting more than half the Rank-Raglan criteria was always a product of chance coincidence or the product of causal influence, either way we can still conclude that it would be very unusual for any historical person to fit more than half the Rank-Raglan criteria—because if it were not unusual, then many historical persons would have done so.

(Carrier, pp. 231f)

Appeal is sometimes made to a satirical essay by Francis Lee Utley, Lincoln Wasn’t There, Or, Lord Raglan’s Hero, as evidence that Raglan’s archetypes have no value at all in assessing historicity. What is not always realized by those who point to Utley, however, is that he was writing satire and to make his case work he had to bend the rationalizations beyond breaking point as can be seen by an apologist making use of Utley’s assertions. Alan Dundes comments on Utley’s essay (p. 190):

The significance of Utley’s essay is that it underscores the distinction between the individual and his biography with respect to historicity. The fact that a hero’s biography conforms to the Indo-European hero pattern does not necessarily mean that the hero never existed. It suggests rather that the folk repeatedly insist upon making their versions of the lives of heroes follow the lines of a specific series of incidents. Accordingly, if the life of Jesus conforms in any way with the standard hero pattern, this proves nothing one way or the other with respect to the historicity of Jesus.

Carrier might add, of and by itself it allows Jesus a one in three chance of being historical.

Carrier’s point is that it is very unusual (he says it has never happened) that a historical person scores as high as many obviously mythical persons, including Jesus, on the list. (Is it kosher at this point to turn the tables and ask if the reason Gullotta was so keen to limit the number of Raglan’s points against Jesus to as few as four was to use the list to argue for Jesus’ historicity?)

And that means we can put that specific data (the Rank-Raglan-assigning data) in our background knowledge and see what it gets as an expected frequency: how often are people in that class historical vs. ahistorical? Because, given the fact that Jesus belongs to that class, the prior probability that Jesus is historical has to be the same as the prior probability that anyone we draw at random from that class is historical.

(Carrier, p. 239)

What is Carrier’s final argument, then? It may surprise Gullotta to learn that Carrier, in arguing a fortiori, was prepared to accept that chances of Jesus being historical even though a high scorer on the Raglan list was one in three.

Again, even if we started from a neutral prior of 50% and walked our way through ‘all persons claimed to be historical’ to ‘all persons who became Rank-Raglan heroes’, we’d end up again with that same probability of 1 in 3. For example, if again there were 5,000 historical persons and 1,000 mythical persons, the prior probability of being historical would be 5/6; and of not being historical, 1/6. But if there are 10 mythical men in the Rank-Raglan class and 5 historical men (the four we are granting, plus one more, who may or may not be Jesus), then the probability of being in that class given that someone was historical would be 5/5000, which is 1/1000; and the probability given that they were mythical would be 10/1000, which is 1/100. This gives us a final probability of 1/3, hence 33%. No matter how you chew on it, no matter what numbers you put in, with these ratios you always end up with the same prior probability that Jesus was an actual historical man: just 33% at best.

(Carrier, pp. 243f)

That is, Carrier is willing to concede for the sake of argument that a high number of the Raglan archetypes can be found to apply to many historical persons as well as many more mythical ones, one in three.

Given Gullotta’s insistence that Jesus fell short of even half the Raglan elements I suspect he would not be willing to argue that a third of all those we could find in the high end of the Raglan types would be historical. (One wonders if Gullotta’s criticism might have taken better turn if there was no prior animus against mythicism or presumption that any mythicist argument is by nature flawed in both motives and methods.)

So what is the point?

Is there any validity to using a twenty-two point Raglan scale or anything comparable in the first place? Should Carrier not have placed Jesus in a Rank-Raglan reference class to begin with?

I think we can begin to get a handle on that question if we reflect on one of the more mundane or Raglan’s elements as addressed by Dundes:

Raglan’s pattern provides a new vantage point for those who seek to understand the life of Jesus as it is reported in the gospels. For example, Bible scholars have bemoaned the lack of information about the youth and growing up of Jesus. Luke and John tell us almost nothing of the period between birth and adulthood. The point is that this is precisely the case with nearly all heroes of tradition. That is why Raglan included his trait 9 “We are told nothing of his childhood” (1956:174).

(Dundes, p. 191, my bolding)

Here an “argument from silence” finds significant explanatory power. The silence is to be expected in the creation of a mythical hero. (The only exception is that sometimes the hero displays some unusual quality through a childhood incident — another archetypal feature in some lists — as we read of the boy Jesus astonishing priests in the temple.)

It is true that Carrier did not have to begin by placing Jesus in such a mythical reference class. Carrier himself acknowledges that possibility. And it is not necessary to begin an argument for a mythical Jesus by setting him in such a category.

But what will have to be addressed at some point in the broader argument when all the evidence is being laid out on the table is the fact that, as Gullotta acknowledges,

- In the Paul’s letters Jesus fits 4 or 5 of Raglan’s elements;

- In the Gospel of Mark he fits at least 7 or 8 of them;

- In the Gospel of Matthew he fits at least 8 or 9;

- In the Gospel of Luke even more [though Gullotta stops short at Matthew, however]

and by the time we get to Justin Martyr and learn that Mary was descended from David along with various other details, we find that Jesus does indeed meet many more than half of the Raglan elements.

The question facing the historian is why so many mythical motifs are found in the life of Jesus according to his growing number of followers.

The historian is faced with a question. Are these mythical features imputed into the figure of Jesus in later generations of believers or do they originate from genuinely historical events? Or do they for some reason simply come out of the minds of followers and attach themselves to the historical memory of Jesus?

The answer to that question will not necessarily be that Jesus was a mythical figure from the beginning. Remember Cyrus, for example. Even Alexander the Great scores seven points. (Carrier argues with more mathematical precision and suggests that no historical person has scored more than half of Raglan’s twenty-two motifs.) What it means is that the probability that any figure who matches a large number of mythical points is more likely to be mythical than historical. We must always allow for exceptions, of course, and Carrier is willing to allow for every one in three being an exceptional historical person who just happens to have accrued more than eleven Raglan points.

Carrier begins with a prior probability of Jesus being mythical by placing him in the Rank-Raglan myth classification. That is, he begins with a prior probability that Jesus was historical at 33%.

He could have approached it differently and kept the RR classification tucked away at element 48 of background knowledge to be considered in the course of any examination of the evidence for Jesus. If he had done that then he would merely have delayed the moment of truth when that evidence would have been addressed and fed into the pool of all the other evidence for and against Jesus’ historicity.

It won’t really matter what you start with to determine prior probability, however, because whatever you don’t use for that will become a part of e (the evidence) anyway, which you will then have to deal with later, and when you do you will get the same mathematical result regardless.

(Carrier, p. 239)

The end result would have been no different if the evaluation is the same no matter at what point of the argument one addresses it: that at best only one in three persons who score high on the Rank-Raglan hero type list are historical.

Doesn’t this presuppose that Jesus began as a Rank-Raglan hero? No. Even if his story was rebuilt so that he would only belong to that class later (for example, if Matthew was the first ever to do that), it makes no difference. Regardless of how anyone came to be a Rank-Raglan hero, it still almost never happened to a historical person (in fact, so far as we can actually tell, it never happened to a historical person, ever). Many of the heroes in that class may well have also begun very differently and only been molded into the Rank-Raglan hero type later. Thus, being conformed to it later has no bearing on the probability of this happening. The probability of this happening to a historical person, based on all the evidence of past precedent that we have, is still practically zero. Even at our most generous it can be no better than 6%. Unless we reject the data we have and suppose that there were more historical persons in that class than the evidence suggests. But even when we do that, it goes beyond reason to estimate the number of such persons at any more than 1/3 of those in the class (and even that is beyond reason in my opinion). Which entails a maximum 33% prior probability that any member of that class was historical.

(Carrier, p. 244)

Or in other words, if all we had for Jesus is the mythic-hero list and nothing else then we could not decide whether Jesus was historical or not. At best we could only surmise that he had a one in three likelihood of having existed. What must tip the scale for or against that surmise is consideration of all the other evidence.

What if we began instead with Jesus being in the reference class of brothers of apostles?

If we began with the argument that Paul met Jesus’ brother, James, then we would need to be careful to think like a historical researcher (see other posts on Finley, Tucker, et al) and translate that into an argument that we have a manuscript from a certain date which stated that Paul met James, “the brother of the Lord”, and assess that evidence against other data, including the point that stories of Jesus over time came to resemble a typical mythical hero. If the other evidence is strong enough then the one in three probability of a historical person ringing a high bell on Raglan’s scale won’t decide the matter against historicity. But at least the historical researcher will have established a sound and honest argument.

–o0o–

Not finished yet…..

–o0o–

Carrier, Richard. 2014. On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press.

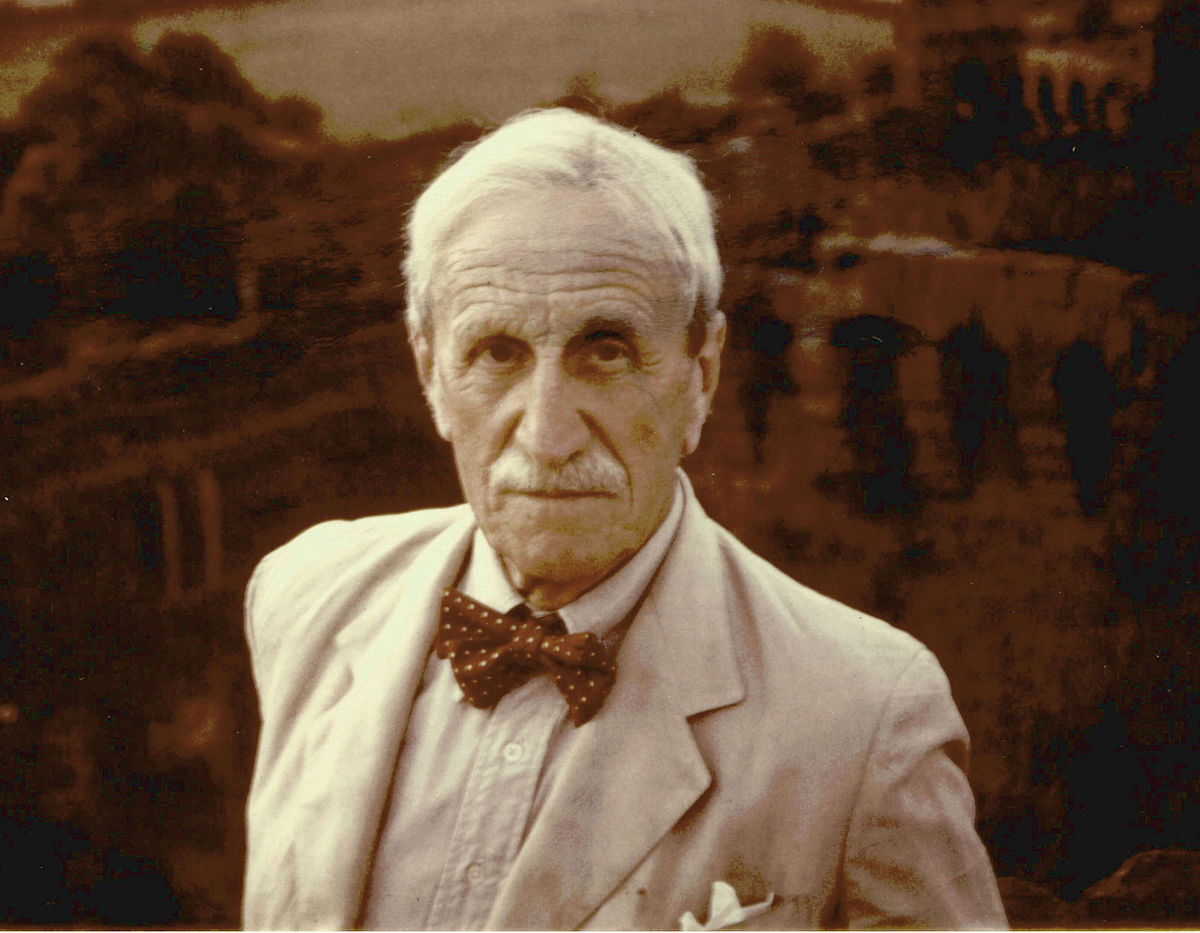

Dundes, Alan. 1990. “The Hero Pattern and the Life of Jesus.” In In Quest of the Hero. The Myth of the Birth of the Hero / [by Otto Rank]. The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama: Part 2 / [by Lord Raglan]. The Hero Pattern and the Life of Jesus / [by Alan Dundes] ; with an Introduction by Robert A. Segal. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press.

Gullotta, Daniel N. 2017. “On Richard Carrier’s Doubts.” Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 15 (2–3): 310–46. https://doi.org/10.1163/17455197-01502009.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Here is an interesting Rank-Raglan list compiled by Professor Thomas J. Sienkewicz which includes historical figures scoring over half on the scale: https://department.monm.edu/classics/Courses/Clas230/MythDocuments/HeroPattern/

I think Professor Thomas J. Sienkewicz has been guilty of stretching the criteria, I only checked the post for Tsar Nicholas and found at least a couple of the +1 to be very dubious indeed.

Sienkewicz’s treatment of Tsar Nicholas is not too dissimilar from Utley’s satirical application of RR to Abraham Lincoln.

What is of interest, though, is that Sienkweicz’s list contains at very best (e.g. if we are willing to believe names like those of Mohammad were also historical) one historical person to two mythical ones: the very best odds Carrier granted.

Neil, the previous post which A Buddhist commented on favorably I thought was remarkably well done, and I wanted to say that, before asking a question. (This one is good, too!) Above, it’s indicated that the scholars complain that there is little information about the youth of Jesus. But what about the infancy narratives? Given that, in the ferment of the original composition of all these stories, none of them were canonical, what prevents the scholars from considering those narratives as some type of evidence of J’s childhood? For that matter, why are the Gnostic or Nag Hammadi scriptures never considered? Wouldn’t the failure to consider them indicate a prejudice in favor of religious orthodoxy, and wouldn’t such a prejudice invalidate historical inquiry?

Clarke, your comment came to mind when I re-read the following in Carrier’s OHJ, p. 13:

A question I have often wondered about is what is the more likely: that a narrative with a historical setting might emerge out of “mythical view” of Jesus or that the mythical Jesus of the Nag Hammadi and other gnostic literature would emerge out of a historical event?

The conventional answer to this question always seems to be hijacked by our dating of the sources. And the dating of the sources is in turn governed by the conviction that the historical events did happen even though they have been lost behind mythical overlay and that our sources must by necessity be dated as close as technically possible to those events in order to have any function at all as the topsoil through which we must dig to find the evidence of “what really happened”.

The method and assumptions upon which the dating of our sources is based in historical Jesus studies is very similar, I think, to the situation that has long faced the studies of “biblical Israel” among “Old Testament” scholars. It took the “minimalists” — Philip R. Davies, Thomas L. Thompson, Niels Peter Lemche, Keith W. Whitelam — to break through that tradition of conventional thinking. They suffered enough at the hands of their peers but in the end their methods and revised perspectives continue to gain ground.

If they treated so badly those who questioned Abraham and David …..

Mack, Burton L. (1990). “All the Extra Jesuses: Christian Origins in the Light of the Extra-Canonical Gospels”. Semeia. 49: 169–176.

Carrier is willing to concede for the sake of argument that a high number of the Raglan archetypes can be found to apply to many historical persons as well as many more mythical ones, one in three.

Carrier (8 July 2018) [now bolded]. “James McGrath Gets Everything Wrong (Again)”. Richard Carrier Blogs:

Ibid. above:

Yeah, like many of the points in Gullotta’s criticism, Gullotta overplays his hand, but at the same time Carrier provided easy targets (however the point of his book was to provide a full overview of all the material). IMO the RR classification is so weak its not even worth mentioning, except in the context of a survey of all the material as Carrier is doing. All mentioning RR does is open one’s self up to just these kinds of criticisms. I mean its much more useful to just directly compare Jesus to Enoch and Elijah and Isaiah and other various messianic and apocalyptic stories from the 2nd century BCE – 1st century. These provide clear parallels instead of an abstract system that anyone will admit doesn’t prove anything.

So again, nothing Carrier said is wrong, and its all very legitimate, and Gullotta’s case is overstated and misrepresents what Carrier did say, but in the end the RR classification system was never worth defending in the first place, so really should just be left out of any serious case against historicity.

Still it was appropriate for Carrier to include it in this book, because the point of this book is to review all the proposals and points that had been put forward for mythicism, so it warranted a mention by Carrier to give a full survey of the relevant material. It’s just not a point worth anyone ever repeating again IMO :p

Carrier (15 November 2016) [now bolded and formatted]. “Two Lessons Bart Ehrman Needs to Learn about Probability Theory”. Richard Carrier Blogs:

Well, seeing as Christianity came about in the Roman empire and the gospels and Paul’s letters were written in Greek, you would have to also compare Jesus to Greco-Roman gods. It wouldn’t make sense to just compare Jesus to Jewish religious figures. You can’t get the full picture by ignoring the Greco-Roman side of Christianity, especially when there are so many similarities to Greco-Roman heroes/saviors. Some of the earliest writings we have on Christianity compares Jesus to the Greco-Roman heroes/saviors/mystery cults. If you take Judaism and mix it with Greco-Roman religion you get Christianity. It’s a perfect mix of both.

Lanzillotta, Lautaro Roig (2010). “Christian Apologists and Greek Gods”. In Bremmer, Jan N.; Erskine, Andrew. The Gods of Ancient Greece: Identities and Transformations. Edinburgh University Press. p. 453. ISBN 978-0-7486-4289-2 :

“[Per Justin Martyr] If divine figures, whether or not originally divine, such as Asklepios, Dionysos, Herakles, the Dioskouroi, Perseus, Bellerophon and Ariadne, were also transported to heaven after death, he [Justin Martyr] seems to argue, there is no need to ridicule Christian beliefs.”

Yeah, and when a lot of those divine figures also performed miracles like raising people from the dead, healing blind men, turning water into wine and were born to mortal women who were impregnated by a god there is no need to ridicule people for comparing them to Jesus.

There was a lot less Greco-Roman influence on the origins of the Jesus cult than most mythicists argue. And in fact these arguments significantly discredit the case against historicity.

The reality is that there was a lot of Greco-Roman influence on the DEVELOPMENT of Christianity. Also, many of the early apologists drew comparisons to Greek gods in order to try and legitimize Christianity. But the reality is that Jesus was a Jewish invention that got appropriated by Greeks and Romans. There was actually minimal Greco-Roman influence on the origins of the Jesus cult.

Basically the pre-war cult of Jewish and the post-war (First Jewish-Roman War) religion was Greco-Roman.

I get Carrier’s point that the figures who score well on the RR are mostly mythical, but I’m still trying to get my head around Carrier’s further inference that thereby scoring well on the RR makes it more likely than not that an individual is mythical.

– Consider this analogy to Carrier’s application of the Rank Raglan hero mythotype:

Freemasons generally exhibit the following 10 characteristics:

1 Compassionate: A real man does not intentionally cause pain, and is sensitive to the needs of others. He cares about other people’s happiness and is empathetic in their sorrows.

2 Faithful: It is vital that a man be true to himself and the people in his life. He does not cheat or betray, and submits to his chosen morals with integrity.

3 Confident: Self-assurance, not pride, is a driving force for a real man. He knows where he is going and why, and is following a path to achieve his goals.

4 Respectful: Every individual deserves respect, and a real man acts in a way that is respectful of all others he encounters, not just his superiors or figures of authority.

5 Humble: All men must be willing and able to account for the mistakes he has made, taking ownership to right any wrongs, and practicing humility when he falls short.

6 Courageous: Bravery and courage are aspects of humanity that all real men must enact. He stands up for what’s right, and always protects women, children and the weak.

7 Hard Working: All men and women have duties, and a real man works hard to fulfill his responsibilities, striving to succeed and to meet additional goals and aspirations.

8 Capable: A manly man respects and appreciates care and help from others, and yet is fully independent and capable to maintain his person, his home, and his livelihood.

9 Passionate: Whether it be in work, hobbies, or relationships, a real man is passionate about something.

10 Humor: Pride and ego have no place in a real man’s character. He should be able to laugh at himself and cultivate good humor in his interactions with others.

* This is all well and fine for describing the characteristics of Freemasons, but we wouldn’t extend the argument further to claim that if anyone exhibits most of these qualities, it is more likely than not that they are a Freemason. That an entity’s description agrees with the description of entities that fit into a certain category doesn’t imply that entity also belongs to that same category. There seems to be a paralogism here on Carrier’s part.

Anyway, I’m still thinking about it.

The Freemason list is a set of motherhood qualities telling the world that Freemasons are fine and good people like other fine and good people, displaying the motherhood characteristics we expect of good people of any belief system to have.

A Raglan list is quite different. It is a result of an analysis of hundreds, possibly thousands, of folk tales that has sought to find features that are common to the central hero in all of them and that make them different from other stories and central characters.

A comparable exercise with Freemasons would, I presume, identify a particular initiation ceremony at a certain point and with certain types of features happens to each member. Another, perhaps (I’m guessing), would be that a vow of secrecy is undertaken. That sort of thing identifies what is distinctive about Freemasons, not that they are “hard working”. But of course there are other organizations that have initiation ceremonies and vows. So we see that Freemasons belong to a certain “type” or “class” of organization. What would characterize them would be a list of common but distinctive attributes.

And then the question becomes one of frequency of the characteristics. Married couples make vows but don’t belong to such organizations. Initiation ceremonies are common to organizations or groups the world over but don’t mean they belong to something like Freemasons. So we come back to how many qualities (half or more? 80% or more?) make it LIKELY that someone belongs to a Freemason type organization.

I’m not sure I follow. To use your language, can we not say Freemasonry originally analyzed “hundreds, possibly thousands” of human personality characteristics “that has sought to find features that are common to the” ideal benevolent man “in all of them and that make them different from” other visions of a man that fall short of these categories?

The point is that, logically, an entity is not likely to belong to a class just because it scores well on a checklist that entities which actually belong to the class exhibit. For instance, being athletic, fast, powerful, well coordinated, athletic, etc, isn’t evidence that you are a football player.

Folklorist Alan Dundes has noted that Raglan did not deny the historicity of the Heroes he looked at, rather it was their common biographies he considered as nonhistorical. Furthermore, Dundes noted that Raglan himself had admitted that his choice of 22 incidents, as opposed to any other number of incidents, was arbitrarily chosen. Lord Raglan took stories about heroes as literal and even equated heroes with gods.

I think we need to keep in mind too that what we call “mythical heroes” scoring high on the RR scale in many cases were in fact regarded as historical figures from the distant past when the poets were crafting the stories about them (e.g., Achilles)

The point is to find distinguishing features of a story or character. Almost all the heroes of the story are of good character, basically well meaning and pursuing noble goals. But those points are not listed because they don’t distinguish the story characters from other heroes or characters in any other type of literature. Freemasons are of good character and well meaning etc. That’s nice. They are like all the other good people we know. Those are the sorts of features that are not listed in the RR class because they serve no distinguishing function.

Your last paragraph is incorrect. It is simply not the case that “many cases” of persons scoring high on the RR scale are or have been “historical figures” or figures found in any other form of literature or daily life. If that were the case then you would be right and the scale would be pointless.

Only be means of satire and absurd exaggerations and distorting the English language to breaking point can Abraham Lincoln be said to be part of the RR list. Ditto for Tsar Nicholas.

A very few historical persons score up to around half, perhaps, on the RR scale.

The RR scale is not a proof of mythicism but it does present data points that are best explained my mythical persons; it increases the likelihood, probability. Exceptions do not change the probabilities.

John, if someone doesn’t agree with the RR classification or its use for the question of HJ studies then it is quite okay to simply ignore it. Have you read Carrier’s OHJ? There are several points I disagree with in it, but I don’t think they make any significant difference to the final result. I suspect omitting the RR business from the discussion will not make any significant difference, either.

But for those of us who do accept its function and value it is something to be thrown into the mix to be addressed in the discussion.

What would really be significant if it could be shown that the RR classification has itself tilted the balance of all the evidence against Jesus being historical.

Accepting for the moment your description of Freemasons:

Suppose one were to assemble a representative sample of men showing most of the characteristics of Freemasons. Suppose further that two thirds of them turned out to be Freemasons, and that for some of the others it wasn’t clear whether they were Freemasons or not.

In that case, given another man showing most of those characteristics, we could reasonably infer that this man is probably a Freemason — about two chances out of three. Of course this estimate would be subject to revision on the basis of additional evidence about this man in particular, such as the presence or absence of the Masonic Square and Compass on the back bumper of his car.

Likewise, Carrier concludes that at least two thirds of Rank-Raglan heroes are non-historical. So if Jesus is a Rank-Raglan hero, he’s probably non-historical as well. That’s a baseline estimate prior to consideration of any more specific evidence.

In practice, there aren’t many Freemasons — about five million worldwide, according to my quick Googling. Of all men showing most of the characteristics of Freemasons, surely only a tiny fraction are actually Freemasons. So your example, considered intuitively, gives a misleading impression of Carrier’s logic.

This is what I am saying is the non sequitur.

Let’s take a more realistic example.

Suppose it were found that 82% of self-identified Republicans approve of President Trump’s performance. I think that’s about the right number, but it changes a bit every time another survey comes out.

Knowing that my next door neighbor considers himself a Republican, but knowing nothing further about his current political allegiances, can I not infer that there’s an 82% chance that he approves of President Trump’s performance?

If that’s a non sequitur, why? Why are the survey results not relevant?

Granted, with more knowledge about my neighbor, I could refine the estimate. If I know he attends an Evangelical church, my estimate goes up. If I know that his car sported a Kasich sticker in the 2016 primaries, my estimate goes down. In either case, we’re talking about probabilities, not certainties. Surely the survey results are a good place to start.

But if it’s not a non sequitur (i.e. it’s just a sequitur), then why is the exact same logic a non-sequitur in the case of Freemasons or Rank-Raglan heroes?

“But the reality is that Jesus was a Jewish invention that got appropriated by Greeks and Romans. There was actually minimal Greco-Roman influence on the origins of the Jesus cult.”

When I say Christianity is influenced by Greco-Roman religion I’m specifically talking about Paul’s letter’s and the other books of the New Testament. Whether there was a Greco-Roman influence before Paul I don’t know for sure but It wouldn’t be surprising seeing as there were hellenized Jews before the 1st century CE. The evidence that by the time of Paul and especially the Gospels Jesus had been turned into a Greco-Roman-Jewish savior/hero is pretty overwhelming.

Perhaps indirectly relevant, the influence of ancient philosophy on the thinking of Paul:

• Troels Engberg-Pedersen: Paul and the Stoics

• Th. D. Niko Huttunen: Paul and Epictetus on Law

• Abraham J. Malherbe: Paul and the Popular Philosophers

Cf. Neil Godfrey (8 April 2012). “Ehrman sacrifices Paul to launch his attack on mythicism“. Vridar.

Carrier is actually a little more clear about what he means by his use of the Rank-Raglan mythotype in some of his interviews than he is in his book “On The Historicity Of Jesus.” To illustrate his argument, Carrier says if you take all the individuals that are mythologized to the extent Jesus is and put their names in a hat, the highest likelihood of pulling the name of an historical person (as opposed to a mythical person) out of the hat is 1/3.

Carrier does actually introduce the “pulling out a name from many in a hat” analogy on page 238 of OHJ as he enters the Rank-Raglan section proper on page 240.