The focus of my response will center on Carrier’s

- claim that a pre-Christian angel named Jesus existed,

- his understanding of Jesus as a non-human and celestial figure within the Pauline corpus,

- his argument that Paul understood Jesus to be crucified by demons and not by earthly forces,

- his claim that James, the brother of the Lord, was not a relative of Jesus but just a generic Christian within the Jerusalem community,

- his assertion that the Gospels represent Homeric myths,

- and his employment of the Rank-Raglan heroic archetype as a means of comparison.

(Gullotta, p. 325. my formatting/numbering for quick reference)

We move on to the sixth and final focus of Daniel Gullotta’s critical review of Richard Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus:

his employment of the Rank-Raglan heroic archetype as a means of comparison.

Let’s begin with Gullotta’s own explanation of what this term means:

Developed originally by Otto Rank (1884–1939) and later adapted by Lord Raglan (FitzRoy Somerset, 1885–1964), the Rank-Raglan hero-type is a set of criteria used for classifying a certain type of hero. Expanding upon Rank’s original list of twelve, Raglan offered twenty-two events that constitute the archetypical ‘heroic life’ as follows:

1. Hero’s mother is a royal virgin;

2. His father is a king, and

3. Often a near relative of his mother, but

4. The circumstances of his conception are unusual, and

5. He is also reputed to be the son of a god.

6. At birth an attempt is made, usually by his father or his maternal grandfather to kill him, but

7. he is spirited away, and

8. Reared by foster-parents in a far country.

9. We are told nothing of his childhood, but

10. On reaching manhood he returns or goes to his future Kingdom.

11. After a victory over the king and/or a giant, dragon, or wild beast,

12. He marries a princess, often the daughter of his predecessor and

13. And becomes king.

14. For a time he reigns uneventfully and

15. Prescribes laws, but

16. Later he loses favor with the gods and/or his subjects, and

17. Is driven from the throne and city, after which

18. He meets with a mysterious death,

19. Often at the top of a hill,

20. His children, if any do not succeed him.

21. His body is not buried, but nevertheless

22. He has one or more holy sepulchres.While Raglan himself never applied the formula to Jesus, most likely out of fear or embarrassment at the results, later folklorists have argued that Jesus’ life, as presented in the canonical gospels, does conform to Raglan’s hero-pattern. According to mythicist biblical scholar, Robert M. Price, ‘every detail of the [Jesus] story fits the mythic hero archetype, with nothing left over …’ and ‘it is arbitrary that there must have been a historical figure lying in the back of the myth’.

(Gullotta, pp. 340f)

For an annotated list of previous posts in this series see the archived page:

Daniel Gullotta’s Review of Richard Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus

Let’s get some clarification and correction here. Otto Rank was on the lookout for Freudian meaning behind the myths and hence identified elements limited to the lifespan between the hero’s birth and his arrival at adulthood. Lord Raglan never read Rank and had no Freudian interest at all in relation to interpretations and analyses of myths. Contrary to Gullotta’s assertion Raglan did not “adapt” Rank’s “list”. Raglan developed his own list of 22 items, some of which by chance overlapped concepts on Rank’s earlier list.

Clearly, parts one to thirteen correspond roughly to Rank’s entire scheme, though Raglan himself never read Rank.65 Six of Raglan’s cases duplicate Rank’s, and the anti-Freudian Raglan nevertheless also takes the case of Oedipus as his standard.66

65. Raglan, “Notes and Queries,” Journal of American Folklore 70 (October-December 1957): 359. Elsewhere Raglan ironically scorns what he assumes to be “the Freudian explanation” as “to say the least inadequate, since it only takes into account two incidents out of at least [Raglan’s] twenty-two and we find that the rest of the story is the same whether the hero marries his mother, his sister or his first cousin” (“The Hero of Tradition,” 230—not included in The Hero). Raglan disdains psychological analyses of all stripes . . . .

66. For Raglan’s own ritualist analysis of the Oedipus myth, see his Jocasta’s Crime (London: Methuen, 1933), esp. chap. 26.

(Segal, p. xxiv, xxxix, xl)

Folklorist Alan Dundes set out Rank’s outline into a list format in order to compare it with Lord Raglan’s list of 22 points. Notice the way the Rank’s words have been changed for the sake of easier comparison. There is nothing wrong with that in context, but Daniel Gullotta is wrong to use Dundes’ reworded summary in place of Rank’s own outline when he is criticizing Richard Carrier for modifying some of the wording in Lord Raglan’s list.

| Rank (1909) | Raglan (1934) |

| 1. child of distinguished parents | 1. mother is a royal virgin |

| 2. father is king | 2. father is a king |

| 3. difficulty in conception | 3. father related to mother |

| 4. prophecy warning against birth (e.g. parricide) | 4. unusual conception |

| 5. hero surrendered to the water in a box | 5. hero reputed to be son of god |

| 6. saved by animals or lowly people | 6. attempt (usually by father) to kill hero |

| 7. suckled by female animal or humble woman | 7. hero spirited away |

| 8. — | 8. reared by foster parents in a far country |

| 9. hero grows up | 9. no details of childhood |

| 10. hero finds distinguished parents | 10. goes to future kingdom |

| 11. hero takes revenge on his father | 11. is victor over king, giant dragon or wild beast |

| 12. acknowledged by people | 12. marries a princess (often daughter of predecessor) |

| 13. achieves rank and honours | 13. becomes king |

| 14. — | 14. for a time he reigns uneventfully |

| — | 15. – 22. etc …… |

Here is Rank’s outline of the hero myth, but note that I have converted Rank’s paragraph into a list format:

The standard saga itself may be formulated according to the following outline:

- The hero is the child of most distinguished parents, usually the son of a king.

- His origin is preceded by difficulties, such as continence, or prolonged barrenness, or secret intercourse of the parents due to external prohibition or obstacles.

- During or before the pregnancy, there is a prophecy, in the form of a dream or oracle, cautioning against his birth, and usually threatening danger to the father (or his representative).

- As a rule, he is surrendered to the water, in a box.

- He is then saved by animals, or by lowly people (shepherds),

- and is suckled by a female animal or by an humble woman.

- After he has grown up, he finds his distinguished parents, in a highly versatile fashion.

- He takes his revenge on his father, on the one hand,

- and is acknowledged, on the other.

- Finally he achieves rank and honors

Gullotta rhetorically asks

Why does Carrier preference a hybrid Rank-Raglan’s scale of 22 patterns, over Rank’s original 12? Could it be because Rank’s original list includes the hero’s parents having ‘difficulty in conception’, the hero as an infant being ‘suckled by a female animal or humble woman’, to eventually grow up and take ‘revenge against his father’?

(Gullotta, p. 242)

Ever since I read Daniel Dennett’s warning against argument by rhetorical question….

I advise my philosophy students to develop hypersensitivity for rhetorical questions in philosophy. They paper over whatever cracks there are in the arguments. (Dennett’s Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, p. 178)

….I hear a warning alarm and I check things out.

Gullotta’s rhetorical question is rendered null when we see (as I have set out above) that Rank did not say “the hero’s parents [were] having ‘difficulty in conception'” at all. Rank said “the hero’s origin is preceded by difficulties such as” — and the difficulties facing a virgin fiancée and her betrothed in the Jesus’ story are well known.

Moreover, when I read more than the page with the table of numbered points and look into what Rank himself wrote about his outline of hero myths, I find that, contrary to Gullotta’s inference, Rank did indeed include Jesus as a hero who fit his model!

Rank cites for the example of Jesus the prophetic announcements, the virginal mother and miraculous conception, the attempt on his life, his being whisked away to safety. Rank singles out the following details from Luke and Matthew as the key motifs to support his placement of Jesus in the same category as Sargon, Moses, Oedipus, Cyrus (yes, he was clearly historical!), Romulus, Hercules, Zoroaster, Buddha:

- angel sent . . . to a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David

- thou shall conceive in thy womb, and bring forth a son, and shall call his name JESUS. He shall be great and shall be called the Son of the Highest

- seeing I know not a man?

- shall be called the Son of God.

- she was found with child of the Holy Ghost.

- the angel of the Lord appeared unto him in a dream

- And knew her not till she had brought forth her firstborn son

- she brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger

- wise men from the east

- Where is he that is born King of the Jews?

- Herod the king

- the angel of the Lord appeareth to Joseph in a dream, saying, Arise, and take the young child and his mother, and flee into Egypt

- slew all the children that were in Bethlehem, and in all the coasts thereof, from two years old and under

- for they are dead which sought the young child’s life.

So if, as Gullotta rightly pointed out, Lord Raglan held back from detailing the stories of Jesus against his “typical mythical elements” his predecessor, Otto Rank, did not — as we read in detail on pages 39 to 43 of The Myth of the Birth of the Hero.

Those terms Gullotta quotes (“difficulty in conception”) are not taken from his reading of Otto Rank but from another scholar, Alan Dundes, attempting to summarize and compare Rank’s views in a simplistic list. A more accurate summary would allow for the births of the following figures being allocated to the same class as Jesus — as Otto Rank does indeed allocate them.

- Sargon

- Moses

- Karna

- Oedipus

- Paris

- Telephus

- Perseus

- Gilgamesh

- Cyrus

- Tristan

- Romulus

- Hercules

- Zoroaster

- Buddha

- Siegfried

- Lohengrin

Unusual and otherwise miraculous births or conceptions and dire situations threatening the survival of the child would cover it. But one would need to read more of the book than the single page authored by a third party with a graphic layout of simplified tables to know that.

Gullotta’s criticism that Carrier was avoiding Rank’s list because it did not support the mythical interpretation of Jesus so far fails on three grounds:

- Rank himself argued that Jesus did fit a common mythical outline

- Gullotta uses a third party’s truncated summary of Rank’s points and so follows a distortion of what Rank himself wrote

- Rank’s model was an attempt to read Freudian analysis into myths and Raglan’s list was more useful as a more complete outline of myths from a literary perspective

But there is fourth failing in Gullotta’s criticism that I will now address.

Gullotta continues:

But the Rank-Raglan hero-type scale is a rather strange device employed by Carrier (and other mythicists), undoubtedly used to further tilt the scale in favor of mythicism.

(Gullotta, p. 341)

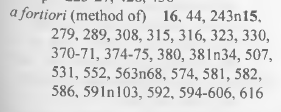

Ouch! That’s an insinuation of deceptive motive. There’s a problem, though. Not once in his review does Gullotta make a mention of any of the more than forty (40+!) times Carrier explains that he is bending over backwards to argue in favour of “historicism”, “against mythicism”, with respect to each piece of data. That is, he is arguing “a fortiori”. If there is any question whether a piece of data might favour either the hypothesis that Jesus was a myth or was a historical figure, Carrier opts in favour of it pointing towards Jesus being historical.

One would expect a reasonable or honest review to point out this little datum if that review at any point expressed an unsupported belief that the author was attempting to deceive his readers with a stacked deck.

Some points by Carrier that Gullotta ought to have addressed to balance his ad hominem innuendo that Carrier was attempting to slant the scholarship in his favour:

To ascertain these probabilities with the kind of vague, problematic and incomplete data typically encountered in historical inquiry, you must estimate all four probabilities as being as far against your most preferred theory as you can honestly and reasonably believe them to be. . . .

Nevertheless, because I want to produce a prior probability as far against myth as I can reasonably believe it to be, so as to produce an argument a fortiori to my eventual conclusion, 1 will ‘grant’ the fundamentalists their unwarranted assumption, even against our background evidence, and count Moses and Joseph as historical persons. . . .

When estimating probabilities, I shall use the method of arguing a fortiori, in each case I will settle on the probability that is the furthest in favor of [historicity] that I can reasonably believe it to be. . . .

But I am committed to erring as far against the mythicist hypothesis as is reasonably possible, so I will assume this ratio to be 2 to 1. . . . In fact, to argue even more a fortiori, I’ll allow (even against all reason) that there could be as much as an 80% probability that this would happen to a historical Jesus (which makes the odds 4 to 5), even though I think that’s absurd. . . . .

For the sake of arguing a fortiori, let’s just assume the traditional account of them is correct . . . .

A more ardent skeptic could disagree. Here 1 am arguing a fortiori, and as such granting historicity its best shot. . . . .

However, arguing a fortiori, I shall say it cannot reasonably be more than 80% likely. . . . .

I believe this passage has been multiply corrupted and originally said something a bit different from the present text (see earlier note), but to argue a fortiori, I shall operate on the assumption otherwise. . . . .

However, I must argue a fortiori, and to that end I shall say it’s reasonably possible these probabilities go the other way around. In other words, that Paul would speak like this on those two occasions could be only 50% expected on mythicism but exactly what we expect on historicity . . . . .

In other words, when arguing a fortiori, if we assume the evidence in the Epistles is exactly 100% expected on h (minimal historicity), . . . . .

Nevertheless, the a fortiori estimates are intended to be as generous to the biases of historicity defenders as I can reasonably be, to the point of outright Devil’s advocacy. . . . .

Thus, I have made two estimates in every case, one a fortiori (the most favorable to historicity as I can reasonably be), and the other realistic (closer to what I honestly think those probabilities actually are). That gives us an upper and a lower bound. . . . .

(Carrier, p. 16, 243, 288-89, 316, 507, 531, 563, 592, 594, 595, 596)

Even the index (p. 681):

So far we have seen Gullotta question why Carrier does not use the earlier and shorter Rank list rather than the longer Raglan list and we have seen that Rank, the Freudian, had a quite different interest and intent from Raglan.

We have next seen that Gullotta’s understanding of Rank’s list is derived from a simplistic summary by Dundes and conflicts with Rank’s own examples of how his mythical elements are to be applied. Rank’s own discussion places Jesus firmly within his mythical types. Gullotta’s inferences that Rank’s “list” would not suit Carrier’s purpose are thus seen to be void.

We have further seen that Gullotta’s insinuation that Carrier was using the Rank-Raglan classification scheme to stack the deck in favour of mythicism contradicts the clear statements of purpose and demonstrations of argument throughout his book. If Gullotta’s accusation is to carry weight it will need to be accompanied by supporting argument that addresses Carrier’s evident points to the contrary.

Next, Gullotta makes the following damning accusation:

Futhermore, Carrier changes Raglan’s traditional list and does not inform his readers how and why he is doing this. For example, Carrier changes the specificity of the ‘hero’s mother is a royal virgin’, to the more ambiguous ‘the hero’s mother is a virgin’.116 He modifies that the hero’s ‘father is a king’ to the far more open ‘father is a king or the heir of a king’ in order to include Jesus’ claimed Davidic lineage.117 He also excludes from his scale that the attempt on the hero’s life at birth is ‘usually by his father or his maternal grandfather’. Carrier adds the qualifying ‘one or more foster-parents’ when the hero is spirited away to a faraway country, while Raglan only states ‘foster-parents’.118 A significant change Carrier makes is that the hero is only ‘crowned, hailed or becomes king’ whereas Raglan states that the hero ‘becomes king’.119 Another important change made by Carrier is that the hero’s ‘body turns up missing’ whereas Raglan’s list has that the ‘body is not buried’.120 After examination, it is clear that Carrier has modified Raglan’s qualifications in order to make this archetypal hero model better fit the Jesus tradition.

(Gullotta, pp. 342f)

Gullotta has a point here. Carrier would have done better to have explained why he appears to have modified Raglan’s list. Nonetheless, the critical reviewer also had a responsibility to have actually read Raglan’s work so that his criticism was based on an informed understanding. Gullotta has taken a summary list, much more easily digested than a reading of full paragraph formats that discuss and explain the points, and pedantically applied a narrow literal reading of that list as the standard by which to fault Carrier. Had Gullotta read Raglan’s own explanations and examples he would have seen that his criticism was misplaced and that Carrier was working entirely within Raglan’s purview.

So Raglan begins his list of examples:

The pattern, then, is as follows:

(1) The hero’s mother is a royal virgin [Carrier adds, or virgin];

(2) His father is a king [Carrier adds, or heir of a king], and

(3) Often a near relative of his mother, but

(4) The circumstances of his conception are unusual, and

(5) He is also reputed to be the son of a god.

(6) At birth an attempt is made, usually by his father or his maternal grandfather, to kill him [Carrier excludes “usually by his father…”], but

(7) He is spirited away, and

(8) Reared by foster-parents[Carrier adds “one or more foster parents”] in a far country.

(9) We are told nothing of his childhood, but

(10) On reaching manhood he returns or goes to his future kingdom.

(11) After a victory over the king and/or a giant, dragon, or wild beast,

(12) He marries a princess, often the daughter of his predecessor, and

(13) Becomes king [Carrier adds ‘crowned, hailed or becomes king’]

(14) For a time he reigns uneventfully, and

(15) Prescribes laws, but

(16) Later he loses favour with the gods and/or his subjects, and

(17) Is driven from the throne and city, after which

(18) He meets with a mysterious death,

(19) Often at the top of a hill.

(20) His children, if any, do not succeed him.

(21) His body is not buried [Carrier writes, “body turns up missing”], but nevertheless

(22) He has one or more holy sepulchres.Let us now apply this pattern to our heroes . . . .

(Raglan, p. 138)

In the following table I have set out just six of Raglan’s twenty-two elements along with Raglan’s own illustrations of how he applied those elements to various mythical figures. The six I have selected are the same that Gullotta criticized Carrier for rewording in some way. Notice, however, how Raglan’s own application of those headings does in fact imply some rewording. One might say that the different approaches are those of the letter versus those of the spirit of the law.

| (1) The hero’s mother is a royal virgin |

(2) His father is a king | (6) At birth an attempt is made, usually by his father or his maternal grandfather, to kill him | (8) Reared by foster-parents | (13) Becomes king | (21) His body is not buried | |

| Theseus | Cousins wish to kill him | Reared by maternal grandfather | Unknown burial place | |||

| Heracles | Hera tries to kill him | |||||

| Jason | Mother is a princess | His uncle tries to kill him | Reared by a centaur | Unknown burial place | ||

| Bellerophon | Mother is a princess | Unknown burial place | ||||

| Pelops | Mother is a demigoddess | Father kills him and gods resurrect him | ||||

| Asclepios | Reared by a centaur | Becomes a man of power | Unknown burial place | |||

| Dionysos | No burial place | |||||

| Apollo | Hera threatens him | |||||

| Joseph | Mother is daughter of a patriarch | Father is a patriarch | Brothers attempt to kill him | Becomes ruler of Egypt | ||

| Moses | Principal family of Levites | Principal family of Levites | Pharaoh attempts to kill him | Reared secretly | ||

| Elijah | Becomes a sort of dictator | |||||

| Watu Gunung | Father is a holy man | No mention of his burial | ||||

| Nyikang | Mother a crocodile princess |

|||||

| Arthur | Father is Duke of Cornwall | No danger | Reared in distant part of country | |||

| Robin Hood | Father is either a Saxon yeoman or great noble | Becomes King of May and ruler of the forest | Various places of burial |

According to Raglan’s own interpretation, an element under the rubric of “father is a king” is read literally when the story involves kings but in other contexts a parent of some prominence in another field fits the bill. At the same time, very few myths contain all 22 elements so in the absence of any of them does not change the mythical character of a story that contains a good many others.

In the next post we’ll look at the rationale for the Rank-Raglan hero classification in the first place.

Carrier, Richard. 2014. On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Dundes, Alan. 1990. “The Hero Pattern and the Life of Jesus.” In In Quest of the Hero. The Myth of the Birth of the Hero / by Otto Rank. The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama: Part 2 / [by Lord Raglan]. The Hero Pattern and the Life of Jesus / [by Alan Dundes ; with an Introduction by Robert A. Segal. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press.

Gullotta, Daniel N. 2017. “On Richard Carrier’s Doubts.” Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 15 (2–3): 310–46. https://doi.org/10.1163/17455197-01502009.

Raglan, Lord. 1990. “The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama: Part II.” In In Quest of the Hero. The Myth of the Birth of the Hero / by Otto Rank. The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama: Part 2 / [by Lord Raglan]. The Hero Pattern and the Life of Jesus / [by Alan Dundes ; with an Introduction by Robert A. Segal. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press.

Rank, Otto. 1990. “The Myth of the Birth of the Hero.” In In Quest of the Hero. The Myth of the Birth of the Hero / by Otto Rank. The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama: Part 2 / [by Lord Raglan]. The Hero Pattern and the Life of Jesus / [by Alan Dundes ; with an Introduction by Robert A. Segal. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press.

Segal, Robert A. 1990. “In Quest of the Hero.” In In Quest of the Hero. The Myth of the Birth of the Hero / by Otto Rank. The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama: Part 2 / [by Lord Raglan]. The Hero Pattern and the Life of Jesus / [by Alan Dundes ; with an Introduction by Robert A. Segal. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Neil Godfrey: I seriously think that you should submit this series of blog posts to some more academic source – either the University of Newcastle or the scholarly journal where this review was published. Even if Gullotta was not dishonest in writing this review, he seems to have been so incompetent that other scholars should be informed about it.

Past experience has taught me that the group will circle the wagons to protect one of their own. The wagons will then turn into a pack of wolves and attack me. (We are not talking about a normal scholarly field.)

How and why would they attack you, since your writings are not mere allegations, but carefully cited counters to Daniel Gulotta’s flaws as a reviewer of Carrier’s book On the Historical Jesus?

I have removed for now my other comment (and that meant removing your reply to it) because you said I came across as accusatory without cause. I have no doubt been in the business too long now and no doubt fatigue too often gets the better of me.

It’s not a question of “how and why they would” attack me. They do. One of them, a scholar specialist in Aramaic, even wrote a book that was published by the Sheffield Press in which he devoted a lot of space to slandering me, and of course that involved a lot of blatant misquotation of me and ripping words out of context. Some scholars continue to commend his book as giving “the low down” on so-called “mythicists” like me.

Other well respected scholars have blogged both slander and falsehoods about me and what I have written. One of them not long ago even faulted me for my use of civil language in my criticisms implying I was trying to create a false impression of sincerity and honesty.

Even “fellow atheists” accuse my criticisms of certain biblical scholarship as being akin to Holocaust denial. Somehow one atheist group managed to even find a way to accuse me of spreading homophobia!

A story I have told before (forgive me long-timers) but it seems you may not be aware of it: when this blog made it to the rank of the top 10 biblioblogs there was deafening silence from the others (not the usual congratulations); very soon afterwards they got together and redefined biblioblogs in order to exclude vridar from their group altogether and to label it as a “fringe and conspiracy theory” outlier.

The attacks are clearly irrational and presumably grounded in ignorance.

As I said, we are not addressing a normal scholarly field here. Don’t get me wrong. There are many good biblical scholars and I continue to learn much from them. I have invested large sums of money in acquiring their books, either direct purchase or interlibrary loans. I have posted many times on the positives I have learned from them. But when it comes to the historical Jesus especially then something weird happens.

There was a heated debate among scholars of the “Old Testament” that was also very heated — over the existence of “biblical Israel”. The same tactics were used then, too, by the conservatives who literally slandered and falsely represented the arguments of “minimalists”. With the historical Jesus it is that same type of argument only magnified tenfold.

I guess people have gone into the discipline either as believers wanting to learn more about their faith, or as nonbelievers who want to follow up an interest in a faith they once had, etc etc etc. But to suggest that their very foundations, their bed-rock assumptions, are misplaced is to invite trouble.

My posts on Gullotta’s review are not just about Gullotta. Gullotta’s review is the product of a system, a collective, that allows for speculation over sound method, takes little cognizance of logical fallacies, remains largely bubbled off from other disciplines, even the field of history. But we live in a Christian culture, at least as far as its heritage goes, and even many people in other disciplines will defer to theologians when it comes to foundational cultural assumptions such as we have about Jesus.

Not all, because I do know that a good many other scholars raise their eyebrows at “theology” and “biblical studies” even having a presence in serious universities. But it is civil to keep quiet. It is even more necessary for the few seriously critical scholars within biblical studies who do question the historicity of Jesus to keep quiet, or to at least delay “coming out” until they are close to the point of retirement.

Thank you very much for your polite reply. I tend to assume the best of all people, especially people whom I only know through the internet.

I agree that we live in a culture whose consideration of Jesus from all perspectives are too contaminated by Christianity. Even many people who leave Christianity tend to carry with them the assumption (or make the conclusion) that Jesus was the wisest (or among the wisest) people on Earth – an attitude that, in addition to assuming his historicity, makes for difficulty in evaluating his teachings. This is why I look forward to reading Bad Jesus.

Or alleged teachings.

On this blog we have shown how seriously “they” misrepresented Earl Doherty’s arguments; we have seen how seriously “they” misrepresent Carrier’s. “They” have also misquoted and misrepresented my own criticism of some of their methods and arguments. “They” said nice things about this blog before they learned I was willing to give a fair hearing to certain mythicist arguments and from that moment on this blog was exiled from the biblioblogging community and relegated to the conspiracy theory shelf. Gullotta’s review with its many citations has done biblical studies in general a huge favour. It has absolved them all of any requirement of having to read Carrier’s book. That is its function. They are not going to get rid of it. I am the one they will in turn misrepresent and attack.

“I am the one they will, in turn, misrepresent and attack” — I wish you would be shown to be wrong, but, alas, wishes do not make reality.

Even better, offer Gulotta a chance to respond to your posts as a guest author here. I am sure someone as young, ambitious and sharp as he is would not turn that offer down….right?

In all fairness, speaking about him with such accusatory language is hardly the sort of language that will make him feel welcome. I merely mentioned Daniel Gulotta’s incompetence as a reviewer of Carrier’s book On the Historical Jesus, but incompetence can arise due to many factors and strike most people from time to time. You, on the other hand, are speculating about his rudeness towards you before it has manifested.

I second that motion.