Recall the Gospel of Matthew’s portrayal of Jesus delivering a parable of the sheep and the goats at the last judgement: Matthew 25:31-41. Now that’s a parable with a message about good works and no hint of any need to believe in Jesus or the saving grace of Jesus’ death and resurrection. What are we to make of this parable? Here is Bart Ehrman’s view:

What is striking about this story, when considered in view of the criterion of dissimilarity, is that there is nothing distinctively Christian about it. That is to say, the future judgment is not based on belief in Jesus’ death and resurrection, but on doing good things for those in need. Later Christians—including most notably Paul (see, e.g., I Thess. 4:14-18), but also the writers of the Gospels—maintained that it was belief in Jesus that would bring a person into the coming Kingdom. But nothing in this passage even hints at the need to believe in Jesusper se . . . . It doesn’t seem likely that a Christian would formulate a passage in just this way. The conclusion? It probably goes back to Jesus.

(Ehrman, Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet, p. 136. “Coincidentally” Ehrman has posted again on this same line of argument.)

Such an argument demonstrates the power of later “orthodox” Christianity to guide the vision and judgment of a modern scholar. Ehrman relies upon the writings of Paul’s “genuine letters” and the canonical gospels to define his view of what was Christian “tradition”, even how to define Christianity.

It is all too easy to overlook the noncanonical literature that also sheds light on earliest Christianity and at the same time to forget that Paul was a disruptive presence, a most controversial figure, among other early Christians — as his own letters testify.

Another early writing from around the same time as the Gospel of Matthew is the Didache. The Didache purports to be a message by “the twelve apostles to the nations” and it at not point indicates any interest in, or even knowledge of, Jesus as a crucified figure. The eucharist is an important instruction in the Didache but it is a thanksgiving meal without any suggestion of association with a sacrament commemorating the death of Jesus.

Other scholars have also noted Q’s absence of interest in a crucified Jesus.

So to make a judgement that a saying in a gospel is not “distinctively Christian” because it does not conform to Paul’s preaching is to limit one’s view of the landscape of earliest Christianity.

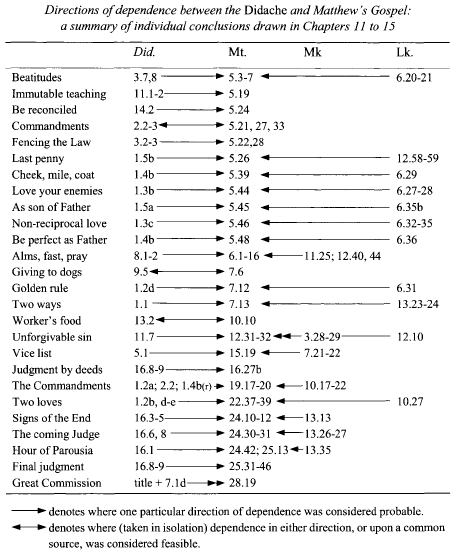

It may even be of interest to note how one scholar sees the relationship between the Gospel of Matthew and the Didache:

Garrow, Alan. 2013. The Gospel of Matthew’s Dependence on the Didache. NIPPOD edition. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 243

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Today on his blog Ehrman wrote:

“Perhaps the criterion can be clarified by providing a couple of brief examples of where it might work. As we have seen, Jesus’ association with John the Baptist at the beginning of his ministry is multiply attested. In some traditions, Jesus is actually said to have been baptized by John. Is this a tradition that a Christian would have “made up”? Well, probably not. For it appears that most early Christians understood that a person who was baptized was spiritually inferior to the one who was doing the baptizing. This view is suggested already in the Gospel of Matthew, where we find John protesting that he is the one who should be baptized by Jesus, not the other way around. What conclusion could be drawn? If it is hard to imagine a Christian inventing the story of Jesus’ baptism, since this could be taken to mean that he was John’s subordinate, then it is more likely that the event actually happened. The story that John initially refused to baptize Jesus, on the other hand, is not multiply attested (it is found only in Matthew) and appears to serve a clear Christian agenda. On these grounds, even though John’s reluctance cannot be proven to be a Christianized form of the account, it might appear to be suspect.”

My comment I posted (awaiting moderation) was:

“Just because later writers found Jesus baptism by John embarrassing doesn’t mean Mark found it to be so. Mark may simply have been inventing a theologically charged story to show Jesus succeeding John the Baptist was even greater than when Elisha succeeded Elijah. As Bob Price says: “In view of parallels elsewhere between John and Jesus on the one hand and Elijah and Elisha on the other, some (Miller, p. 48) also see in the Jordan baptism and the endowment with the spirit a repetition of 2 Kings 2, where, near the Jordan, Elijah bequeaths a double portion of his own miracle-working spirit to Elisha, who henceforth functions as his successor and superior.””

King, Karen L. (2008) [now reformatted]. “Which Early Christianity?”. In Harvey, Susan A.; Hunter, David G. The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Studies. OUP Oxford. pp. 70, 80. ISBN 978-0-19-927156-6. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199271566.003.0004 :

Paul also never says the Red Sox lost the World Series in ’67 so therefor they must have won.

I think Ehrman is just afraid to let go of the laast shred of his belief and I feel bad for him as his earlier books convinced me there is no basis for Christianity.

Didache struck me decades ago as Matthew without the plot. I don’t see any need for the ‘Lost Gospel’ of ‘Q’ with Didache, an actual extant document, as an ur-text. The dates are problematic? The dating of the New Testament appears to me to be massively circular as it is reasoned. If we had disinterred G.Matthew and Didache in the same cache as Eugnostos and The Wisdom of Jesus Christ the emperor’s nudity would be obvious.

Another connection with Elijah/Elisha occurs in one of the non-canonical gospels: Jesus appears at the Jordan and the river reverses course and backs up to its source, leaving the entire bed dry; not just parting it as in the Elijah/Elisha story. More transvaluing and going one up on the original by JC!