Previous posts in this series:

This post needs to be read in conjunction with How Dating the Dead Sea Scrolls Went Awry — #1. We concluded in that post with: “the resetting of the palaeographic dates to conform with artefacts in Qumran was based on three assumptions, all of which were “deeply flawed.”

.

Assumption 1:

All pottery more recent than the Iron Age (age of Assyria, Babylonia, etc) was the product of a settlement in the first century CE era.

Doubts:

The second excavation (1953) uncovered activity from the first century BCE.

Recall that jar embedded in the floor of Locus 2 — it was of the same kind found in Cave 1 with the scrolls.

Coins were found there from the time of Antigonus Mattathias, 40-37 BCE, one right beside that jar.

That jar in Qumran’s Locus 2 was now re-dated to the first century BCE. That is, that room was now BCE, not CE.

But the first century CE date held for the Qumran “community” by arguing that the room was swept clean and re-used through the first century CE by the “community” or people who would be related to the scrolls.

That is, despite the discovery of BCE setting, the CE date for the scrolls failed to budge. 1951 saw the date revised and that revision uncritically held fast despite the new archaeological discoveries.

Although excavator of the site Roland de Vaux belatedly acknowledged in a public lecture that the scroll jars in the caves were indeed from the first century BCE (1959) and eventually published the same point (1962) he never provided specific details. I can imagine that such vagueness did little to prod a critical reevaluation of the widespread acceptance of the first century CE date for the scrolls.

.

Two other assumptions filled the gap left by the awareness of evidence that there was BCE settlement activity and the site was not exclusively CE.

Assumption 2:

(a) A single group controlled and inhabited Qumran throughout the period 150 BCE to 68 CE. (Apart from a short hiatus around the turn of the century.)

(b) Scrolls would have continued to be deposited throughout the entire duration of that settlement — that is, they would have continued to be deposited up to the time of the Jewish War.

Doubts:

This assumption likewise began to crumble:

As is well known, many archaeologists have rejected this second foundational assumption. That is, they reject a Ia/Ib or Ib/II continuity in people and function at Qumran (e.g. Bar Adon, Humbert, Hirschfeld, Magen, Peleg). (Doudna 2017, p. 241)

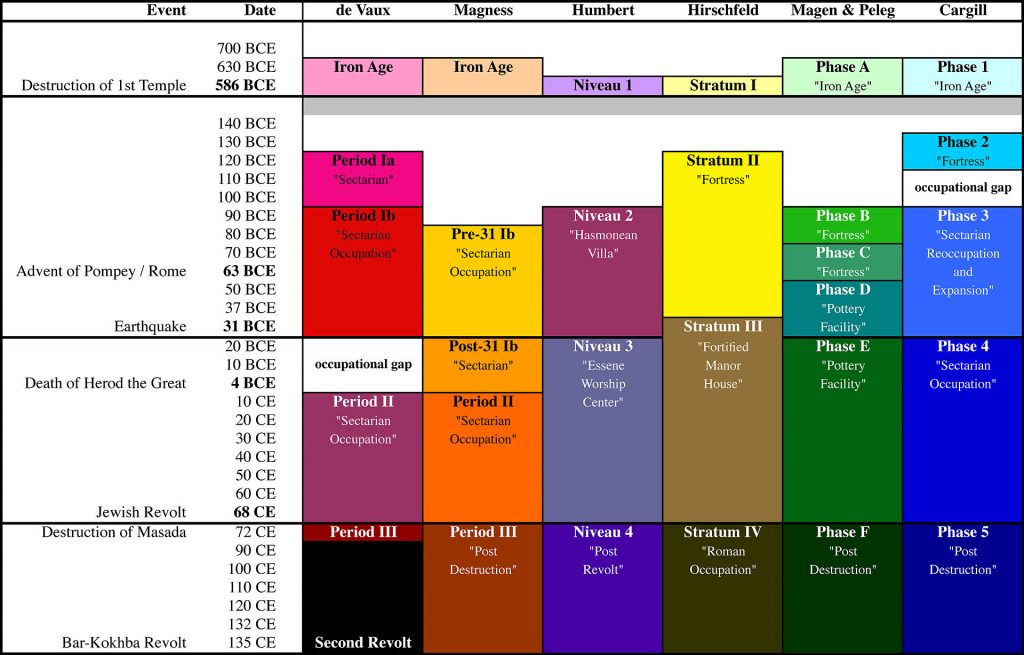

The following table gives us the idea:

Other models propose a non-sectarian community in the final phase up to 68 CE (Bruce and Pfann); and previous posts have set out Stacey’s view that site was a seasonal industrial area linked to Jericho.

Of particular significance is that a number of archaeologists believe the evidence points to the scrolls having been deposited in the caves prior to the first century CE. The scrolls were tucked away in the caves before the time of the occupants of the Qumran site in the first century CE.

Each of these last-named (de Vaux, Bruce and Pfann, Stacey) suppose the latest inhabitants of first-century CE Qumran ending at the First Revolt postdated the major scroll deposits of Cave 1Q, Cave 4Q, etc. In this way a notion of discontinuity in principle between earlier scroll deposits and different, later, non-cave-scrolls-related first-century CE people and activity at the site before the destruction of the First Revolt has been present from the beginning in some de Vaux-aligned archaeological interpretations of Qumran (e.g. de Vaux), even though this point has not generally been appreciated.

In any case, the variety of archaeologists’ conjectures concerning which of Qumran’s pre-70 CE occupants were and were not involved with the deposits of scrolls in the caves betrays the arbitrary nature of such reconstructions. (Doudna 2017, p. 242)

.

Assumption 3:

The refugees or fugitives who left domestic pottery and jars in the caves at the time of the Jewish War (ca 68 CE) were also responsible for depositing the scrolls.

Doubts:

This assumption represents a classic instance of the association fallacy.

But as has often been pointed out, there are countless examples of caves with relics of human activity from different eras of time unrelated to each other in the same cave. No good argument has been set forth for excluding this interpretation — so common in other caves — in the case of scroll-bearing caves of Qumran which also had domestic pottery from the time of the First Revolt (e.g. the scroll jars and scroll deposits date late first BCE; refugee activity dates ca. 60s CE/First Revolt). (Doudna 2017, p. 242)

.

Continuing. . . .

Doudna, G.L. 2017. “Dating the Scroll Deposits of the Qumran Caves: A Question of Evidence.” In The Caves of Qumran: Proceedings of the International Conference, Lugano 2014, edited by Marcello Fidanzio, 238-246. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

http://www.neverendingvoyage.com/sassi-matera-italy/

http://www.boredpanda.com/italian-cave-restaurant-grotta-palazzese-polignano-mare/

http://www.andalucia.com/nerja/caves.htm

Caves being repurposed.