Recently, while watching our favorite apoplectic antimythicist discuss “The Case of the Historical Jesus,” something the Clarence L. Goodwin Chair in New Testament Language and Literature said caught my ear. Here’s what he said:

Historians tend to discount miracle claims and those kinds of things right off the bat, because even if they were to investigate them, the things that people call miracles tend to be things that are inherently improbable . . . But talking about things like walking on water, turning water into wine — most historians won’t even bother discussing those things, because the most a historian ever does is say something is probable. And a historian is never going to tell you that something inherently improbable is probable. And so those kinds of things can be set aside from the outset. (James McGrath, 2016)

Actually, two things drew my attention here. The first is the term inherently improbable, and the second is the claim that historians set aside miracle claims.

Inherently improbable

If you search among books, articles, and academic papers, you’ll find the term inherently improbable used quite frequently in the sciences, liberal arts, religious studies, and the law. But in philosophy (especially logic), you’ll also find people writing about it with some ambivalence.

What exactly do we mean by inherent probability? In his book, Acceptable Premises: An Epistemic Approach to an Informal Logic Problem, James Freeman cites John Nolt’s definition.

We are not talking about a statement’s being probable relative to a set of premises. Rather, we are talking about a statement’s being probable simpliciter. As Nolt points out in (1984), we may distinguish two senses of statement probability. Inherent or absolute probability is “the probability of a statement in and of itself” (Nolt 1984, p. 193). Nolt points out that this sense of probability “can easily be defined in terms of possible worlds. The inherent probability of a statement is just the frequency among all possible worlds of the worlds in which it is true” (1984, p. 193). (Freeman, 2005, p. 16, emphasis mine)

So far, it looks as though the question of miracles fits. On the face of it, in and of itself, would you consider the claim that a miracle occurred inherently improbable? You might think so, but read on.

Given this definition, it is easy to see that it is totally inappropriate to define acceptability in terms of inherent probability. For this definition will require us to count as unacceptable statements whose truth is manifest. For example, suppose you are 5’6″ tall and I can see that you are because you are standing next to a ruler painted on the wall. But, given all the heights you could possibly be, and given the contingency of your existence to begin with, in what proportion of worlds are you 5’6″ tall? Presumably, the proportion of such worlds is very small. So it is inherently improbable that you are 5’6″ tall — and consequently the claim that you are is not acceptable. (Freeman, 2005, p. 16, emphasis mine)

Imagine the set of possible universes in which you exist. Now imagine the set of all possible universes.

In fact, because “in most worlds you don’t even exist” (Nolt 1984, p. 193), it is inherently improbable that you do exist even when you are standing in front of me. I must find the claim that you exist unacceptable! But this is nonsense. Inherent probability is no criterion of acceptability. (Freeman, 2005, p. 16, emphasis mine)

So we see that the notion of inherent probability fails to help us, because it doesn’t take into account what we know about the background knowledge of a situation. Rather than inherent probability, both Nolt and Freeman prefer instead to use epistemic probability, which Nolt defines as “the best estimate of the statement’s truth, based on everything we know.” (Nolt, 1984, p. 193)

It is also worthy of note that negative statements tend to be inherently more probable than affirmative ones. It is inherently improbable, for example, that you have 3,129,732 hairs on your head. The denial of this statement has a much higher probability — in fact, it is inherently almost certain.

Despite its philosophical interest, inherent probability is of little practical value. Usually when we seek the probability of a statement, we want the best estimate of the statement’s truth, based on everything we know. It is of little use to be told, for example, that it inherently improbable that you have the plague, if all the evidence says that you do. Thus what interests us for most practical epistemic probability. The epistemic probability of a statement (the term comes from the Greek word episteme, meaning “knowledge”) is the frequency of worlds in which the statement is true among worlds in which all of what we know about the actual world is true. (Nolt, 1984, p. 193, emphasis his).

Of course in legal circles when people call testimony inherently improbable, they simply mean that it sounds wholly implausible. Similarly, when McGrath calls the miracles in the Bible inherently improbable, he’s alluding to the fact that they describe events that “based on everything we know” seem highly unlikely. The world doesn’t work that way. We assume that the world of the first century of the Common Era operates under the same rules as today’s world. Blindness isn’t healed with spit. Humans don’t walk on water. Virgins don’t give birth to god-men.

Do real historians set miracles aside?

McGrath advances the notion that historians “set aside” all these miracle claims. Bart Ehrman, a New Testament scholar who also likes to call himself a historian, puts it this way:

What about events that do not happen all the time? As events that defy all probabilities, miracles create an inescapable dilemma for the historian. Since historians can only establish what probably did happen in the past, and the chances of a miracle happening, by definition, are infinitesimally remote, they can never demonstrate that a miracle probably happened. . . .

I should emphasize that historians do not have to deny the possibility of miracles or deny that miracles have actually happened in the past. Many historians, for example, committed Christians and observant Jews and practicing Muslims, believe that they have in fact happened. When they think or say this, however, they do so not in the capacity of the historian, but in the capacity of the believer. In the present discussion, I am not taking the position of the believer, nor am I saying that one should or should not take such a position. I am taking the position of the historian, who on the basis of a limited number of problematic sources has to determine to the best of his or her ability what the historical Jesus actually did. As a result, when reconstructing Jesus’ activities, I will not be able to affirm or deny the miracles that he is reported to have done. (Ehrman, 1999, p. 196-197)

Christorians must deal with the conflict between the impossibility of miracles on the one hand, and an audience that believes in them on the other. This conflict often leads to painful, self-inflicted contortions like the one above. But when real ancient historians describe, for instance, the miracles supposedly performed by Roman emperors, they don’t ramble on for five pages, hemming and hawing about how they can’t judge one way or another about the veracity of these claims. They didn’t happen.

Notice how easily and quickly all of us can come to that conclusion. We didn’t have to stop and ponder over the inherent or epistemic probability. They didn’t happen. None of us — lay person or professional — anguished over the “inescapable dilemma” of low probabilities. Why is that?

The logical inconsistency of miracles

Perhaps we didn’t worry about it because miracles aren’t simply improbable. They’re inconsistent. By that I mean the statement of the premise (the report of a miracle) is, by definition, impossible. It is false in all possible worlds. John Nolt, in his book Informal Logic: Possible Worlds and Imagination, explains as follows:

Situations which hold in some worlds but not in others are termed contingent, and statements describing them are contingent statements. Some contingent statements are true in the actual world, and some are actually false. . . . The statement “Germany developed nuclear weapons during World War II” is contingent and, fortunately, false.

There are also, as you know, situations which are logically impossible. The existence of a four-sided triangle is one. You can’t coherently imagine it. Statements describing these situations (e.g., “Four-sided triangles exist”) are termed inconsistent. (Nolt, 1984, p. 169, emphasis his)

An inconsistent statement is impossible in all worlds. Hence, by logical necessity, it is false in our world. Nolt offers the following examples:

- The earth is both flat and not flat.

- My house is a round square.

- 2 + 2 = 3

- Olaf is a husband who has never been married.

- Nothing is green, but my plants are green.

We must rate as false those statements that are mathematically and physically inconsistent with reality. Let’s do a little thought experiment. You know that iron is much denser than water. In fact, the density of water is 1.00 g/cm3, while the density of iron is 7.78 g/cm3. Even if you didn’t know that iron is nearly eight times denser than water, you intuitively knew that a chunk of iron will not and cannot float in water. That statement is true in all worlds.

5. But as one was felling a beam, the axe head fell into the water; and he cried out and said, “Alas, my master! For it was borrowed.” 6. Then the man of God said, “Where did it fall?” And when he showed him the place, he cut off a stick and threw it in there, and made the iron float. 7. He said, “Take it up for yourself.” So he put out his hand and took it. (2 Kings 6:5-7, NIV)

Is it “unlikely” that Elisha caused this axe head to float in water? Or, to use Ehrman’s language, is the probability “infinitesimally remote”? No. In no possible world can an object with a mean density of 7.87 grams per cubic centimeter float in water. Hence, it is an inconsistent statement. (Note: Copper is 8.96 g/cm3.)

The story in 2 Kings doesn’t describe an unusual event; it describes an impossible event. By definition, a miracle is an event that could not occur without supernatural intervention. If I told you that I just ran a four-minute mile, you would consider that highly improbable because in most worlds, it isn’t true (inherently improbable), and because very few people can run that fast, none of whom are over 50 years old (epistemically improbable). So my contingent statement is probably false.

Now suppose I told you I just ran a marathon faster than the speed of light. Is the probability that statement is true “infinitesimally remote”? Not at all. The probability is exactly zero. It is a false statement in all worlds, because nothing in any known world can travel faster than 186,000 miles per second.

What we’re saying here is wholly consistent with the common definition of miracles. A miracle is not a simple parlor trick; it is the suspension or reversal of known physical laws. In Christianity, the belief in miracles has everything to do with the belief that God, having created the natural world, is not bound by its rules. All right, but let’s be clear on the full implications of that belief.

Whose magisterium is it anyway?

Some theologians (hence, some Christorians) believe in the doctrine of Non-Overlapping Magisteria. They contend that science can explain the physical world, but only faith (i.e., their religion) explains the supernatural, metaphysical world. However, belief in miracles requires a belief that one magisterium — religion — does overlap the other. In fact, in a Venn diagram, one magisterium completely contains the other. If supernatural forces can impinge on the natural world at any time, then the magisterium of science is merely a tenant inside the larger world of all things natural and supernatural.

The tools of science — observation, experimentation, physical models, theories, mathematics, etc. — by definition only work in the physical world. So, if you want to posit a universe in which some greater force or forces exist outside those boundaries, go ahead. But please understand that if that’s true, you can’t prove it or describe it using these tools.

How do real historians deal with reports of miracles?

Ehrman and McGrath say that history can only establish the probable, and they’re correct. So, I would conclude, if you claim Jesus performed miracles, you aren’t doing history. You are working in a realm outside the domain in which our tools have any meaningful use. You are attempting to assign probability to an event that is, by definition, not merely improbable, but impossible in all worlds.

Next, Ehrman and McGrath say that miracles are highly unlikely. They are categorically wrong. Miracles have zero probability. They are inconsistent with the physical universe. By definition, they cannot and do not occur in any possible world.

Finally, McGrath says we can set aside miracles, and Ehrman says he can neither confirm nor deny their existence. Again, they are categorically wrong. Ancient historians who write about the lives of the Caesars do not set aside miraculous claims; they explain them. That’s their job.

Why do we have claims that Vespasian healed a blind man? How do such stories come about? Who would invent them and for what purpose? What can we learn from them? See: “A Healing Touch for Empire: Vespasian’s Wonders in Domitianic Rome” by Trevor Luke.

Anyone who thinks historians set aside stories of the supernatural does not know what the hell he is talking about. Scholars posing as historians shouldn’t misinform the public, nor should they teach their students such nonsense.

Ehrman, Bart D.

Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, Oxford University Press, 1999

Freeman, James B.

Acceptable Premises: An Epistemic Approach to an Informal Logic Problem, Cambridge University Press, 2005

Nolt, John Eric

Informal Logic: Possible Worlds and Imagination, McGraw-Hill, 1984

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

http://www.amazon.com/Die-sechste-Stunde-historischen-Naturkatastrophen/dp/3869351934/

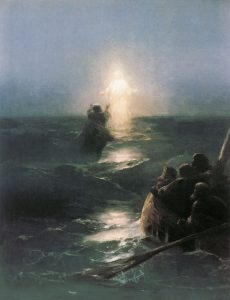

Wouldn’t Jesus walking on water have been a better illustration than a stick –stuck back into a primitive axe head– causing something heavier than water to float [off the bottom]?

Hi, what a great topic. A few comments:

Firstly, when we consider a term like “inherently improbable”, I think we should ask if it is really something which needs to be defined?

To consider an analogy: In physics, we talk about the “distance” of two things all the time, but we can also encounter the term “very distant”. But we don’t worry how “very distant” is defined because it is understood to have no physical meaning: all there is is the distance and “very distant” is just linguistic sugarcoating.

Similarly with probability. The books I am aware of that defines (in an exact sense) probability only considers one concept: the probability. So I would strongly advocate the view that we only talk about probability as one thing.

If we did that, probability would refer to a conditional structure: “The probability of X given other knowledge Y” (i.e. epistemic probability), and the term “inherently improbable” would be a shorthand for something like “on very general considerations the proposition has a very low probability” (compare to “very distant”).

Secondly, I would be worried about defining probabilities in terms of “possible worlds” because you very easily get into all sorts of problems, but that’s a whole other digression (I can give you references if you are interested).

Thirdly, regarding the reason for excluding miracles:

Next, Ehrman and McGrath say that miracles are highly unlikely. They are categorically wrong. Miracles have zero probability. They are inconsistent with the physical universe. By definition, they cannot and do not occur in any possible world.

I think a point a theist (and many philosophers) would raise is that you are considering a too narrow definition of a possible world. For instance, we should also consider possible worlds with different laws of nature, where God existed, where we lived in a simulation and so on.

In other words, they would say that the statement you are making is this:

P(“Miracle occured” | “The laws of nature are never violated”) = 0

which they would say was true but that you, because of your finite knowledge, could not “know” that “the laws of nature are never violated” and so the probability that we should assess is this:

P(“Miracle occured” | “The laws of nature describes the world well at the moment”) = ?

To put this objection in a different way, if we consider there might be a possible world where something like God exist, we could not say it was not our world and so we should not assume this information (not that I believe God exists or that miracles happen).

The second point they would likely bring up is that the miracles in the bible do not have to violate the laws of nature. To take the floating ax-head, what *could* have happened is this: The motion of the water molecules determine the state the water is in. The motion is random (in statistical mechanics we would say it follow the Boltzmann distribution) and so by pure chance the motion of the water molecules could have converged to form a very strong updraft below the ax-head causing it to float. In classical statistical mechanics this is no problem at all; it is just very, very unlikely (i.e. so unlikely we would never see it if the universes history happened a billion times over), so even if we accept that probabilities has to be defined in terms of “possible worlds” that conforms to our laws of nature we cannot reject many miracles as *impossible*.

I agree with you that the quote by Ehrman, “I will not be able to affirm or deny the miracles that he is reported to have done” (I did not know he had ever written it so strongly) is very odd. Actually I can’t believe he actually believes what it says if taken literally, but I think the rejection of miracles can be done using common probabilistic considerations (their low prior probability compared to the quality and strength of evidence) and that the various low-probability paradoxes can be resolved with more detailed analysis.

Tim H.: “The motion is random (in statistical mechanics we would say it follow the Boltzmann distribution) and so by pure chance the motion of the water molecules could have converged to form a very strong updraft below the ax-head causing it to float.”

You are not describing a miracle in this case. You are instead describing the rationalization of a miracle. In such a case, we have the report of a phenomenon that was misunderstood. That’s similar to the notion that Moses and his group of migrants got the the edge of the Sea of Reeds, and a highly unlikely but totally natural wind came and blew a trough in the water that allowed them to cross.

But if you rationalize a miracle, it stops being a miracle. It becomes instead an extremely rare natural event that was misunderstood. Hence, your statement — “so even if we accept that probabilities has to be defined in terms of “possible worlds” that conforms to our laws of nature we cannot reject many miracles as *impossible*” — is a nonstarter. The rationalization of miracles is the rejection of miracles. By taking that path, you’re saying that the supernatural world did not impinge on the natural world.

great post thnx [ to be continued]

Tim H.: “I think a point a theist (and many philosophers) would raise is that you are considering a too narrow definition of a possible world. For instance, we should also consider possible worlds with different laws of nature, where God existed, where we lived in a simulation and so on.”

If the laws were different such that a phenomenon in this world that is impossible becomes possible in that world, then it is simply following a different set of natural rules. It is then not a miracle.

Tim H.: “. . . because of your finite knowledge, could not “know” that “the laws of nature are never violated” . . .

Consider the doctrine of the two natures of Christ. He is 100% human and 100% divine, simultaneously. This doctrine is self-contradicting and can only be accepted as a mystery and a miracle. It is false in all worlds (i.e., in all possible permutations of our universe), because it is an inconsistent statement. It is just as inconsistent as a square circle or a triangle with four sides.

Can I know, even with finite knowledge, that 1 + 1 never equals 4? Yes. Because by definition, a world 1 + 1 != 2 is inconsistent, incoherent, and impossible.

If a theist wants to imagine a world in which such things are possible, then he must agree that none of our tools will work in that world. It’s a magical world where probability and mathematics have no meaning. It’s pure fantasy and silliness.

“If the laws were different such that a phenomenon in this world that is impossible becomes possible in that world, then it is simply following a different set of natural rules. It is then not a miracle.”

I think most philosophers who adheres to Kripkes possible-world semantic considers a possible world as one which is can be described in a logically consistent fashion, that is, as inclusive a definition as possible. So what they would ask is how we can know that a world with one or more God-like creature is logically impossible? (i.e. a world with some entity in it which could change the state of the world depending on what it was thinking, for instance decide to make the ax-head float on top of the water).

Regarding 1+1=2 example, such a world can be ruled out as being logically impossible, but I don’t see how the idea of a creature that can change the conditions of the world depending on what it is thinking is logically impossible. Alving Platinga for instance clearly believes in such a creature and I haven’t seen many other philosophers attacking him on that point alone.

somewhat akin to 1+1 = 2 is Euclid’s 5th postulate that given a straight line and a point, one and only one line that goest through the point is parallel to the first line. Yet there are whole useful geometries where that is not true.

Likewise, if we are in a simulation, the simulation programmer could interject agents that temporarily break the laws using laws from greater environment in which the simulation exists. A simulation perhaps could be built that strictly followed Euclid’s laws.

Lowen: “Euclid’s 5th postulate that given a straight line and a point, one and only one line that goest through the point is parallel to the first line. Yet there are whole useful geometries where that is not true.”

Yes, and in those non-Euclidean geometries parallel lines intersect only because certain Euclidean postulates were relaxed. And in those non-Euclidean constructs, we can predict at exactly what point and at what angle the lines will cross. If they did not obey those rules, it would be a miracle.

Lowen: “. . . the simulation programmer could interject agents that temporarily break the laws using laws from greater environment in which the simulation exists.”

In that case the event would appear to be a miracle, but is in fact operating under rules that are unknown to the actors inside the simulation. They are not aware of the full set of natural, physical rules, but they would be wrong to argue for a supernatural explanation.

I am trying to see if I understand your post correctly. According to your view a “possible world” is one which is logically consistent, operate under laws of nature (which may be different than ours) and where there is no “magic”, i.e. a world with a being which can make things happen by it’s whims is impossible. Therefore a world with a god which makes an ax-head float is impossible. Is this correctly understood?

I guess you would then also accept this argument for atheism?:

1) In no possible world can there be a creature which violates the laws of nature (i.e. makes ax-heads float or raise Jesus from the dead) (assumption)

2) Therefore, it is not possible there is a creature which violates the laws of nature (Kripke, definition of possible)

3) The christian God violates the laws of nature

4) Therefore, the christian God is not possible

5) Therefore, the christian God does not exist

It is of course a matter of definition, but I think many would say that your definition of a possible world is too strict. I wonder what you would say to defend that premise?

Just so we’re clear, I’m using “possible worlds” in Nolt’s sense. Namely, these are imaginary worlds that don’t exist, but they help us understand things, make sense of inferences, assign probabilities, assist with inductive logic, etc. That’s different from the sort of modal realism that says all possible worlds really exist simultaneously with our own.

I’m suggesting that a world in which “impossible things are possible” is incoherent. Hence, what I wrote above:

If you want to argue that worlds are possible in which the impossible happens — well, you certainly have the right to believe whatever you want, but I don’t think you can say anything particularly useful about it. Nor do I think for even a second that we live in such a world.

Hi,

I wasn’t trying to imply you are a modal realist (but I am assuming you are using something akin to Kripkes possible-world semantic where necessary means “true in every possible world etc.”). What I am getting at is how we could convince a skeptical philospher that a world much like our own but with a God who once in a while intervene supernaturally is impossible. I have to disagree that we can’t describe such a world at least in general terms (the OT in the bible does that), however we might of course have problems describing it exactly. But that’s a problem that affect all sorts of possible worlds: we don’t even know if our world is describable exactly using laws of nature and we certainly don’t know what that description is.

But more to the point, with your definition of the many-world semantic, does the above “proof that god exist” follow?

If you want to argue that worlds are possible in which the impossible happens — well, you certainly have the right to believe whatever you want. Nor do I think for even a second that we live in such a world.

I don’t think we live in such a world either. But if it comes down to what we think is true and not what we can demonstrate, then isn’t the proof that miracles take place in risk of simply assuming the conclusion?

1) Assume supernatural violations of the laws of nature is impossible (how I understand the assumption in the OP)

2) Assuming the supernatural is impossible, supernatural events such a miracles do not take place.

As I understand the common definition of a possible world, there may very well be “possible worlds” (not assuming modal realism) with supernatural events. Heck, I think Harry Potter is a possible world because I can’t see how it is logically contradictory. But the chance we live in one is very low and so the chance we should accept a miraculous claim about a miracle comes out as very near zero. That’s a weaker statement than an assumption that supernatural events are impossible in all worlds but IMHO much easier to support.

Tim Hendrix” “operate under laws of nature”

I’m not sure the laws of nature define how things operate; they seem to provide understanding of how things operate – how factors relate to each other.

Yah, sure, I am talking in a qualitative way. The distinction I see in the OP is between a world that operate mindlessly and in a fixed way and in a world where a supernatural agent can will things to happen.

Tim Widowfield: “But if you rationalize a miracle, it stops being a miracle. It becomes instead an extremely rare natural event that was misunderstood. Hence, your statement — “so even if we accept that probabilities has to be defined in terms of “possible worlds” that conforms to our laws of nature we cannot reject many miracles as *impossible*” — is a nonstarter. The rationalization of miracles is the rejection of miracles.”

That’s true if we define miracle to involve breaking the laws of nature (which I agree is the most common definition), but a person could claim that on his view the miracle is simply the floating of the axe-head, regardless of whether it came about by breaking the laws of nature or by an *extremely* improbable event, and God’s role in the miracle was to organize the world just such that the random motion of the molecules conspired to lift the axe-head just at that moment.

Tim H. “God’s role in the miracle was to organize the world just such that the random motion of the molecules conspired to lift the axe-head just at that moment.”

Random events, by definition, are not predictable. In a purely Newtonian world, with knowledge of every possible particle in motion, one could conceive of the possibility of predicting any given event, or even intruding (with butterfly wings?) slightly to change the trajectory of the universe. If so, then the God you describe is merely a very capable scientist with extraordinary skills and knowledge. He would appear to be magical, but only in the Arthur C. Clarke sense of the word.

In the real world, of course, things do occur at random, so even if you could overcome the practical limitations, you can’t predict the unpredictable. Only a transcendent, supernatural being could do so.

Getting back to our discussion of ancient history, no historian would lose sleep over whether Vespasian really performed miracles. Nor would he or she “set aside” these stories. Further, no historian would invent weird scenarios in which people thought they witnessed miracles, but were mistaken.

No, these reports were Roman propaganda. That’s the simple explanation. No need to agonize over it. It’s only when we shift over into reports that appear in religious texts (hence, less reliable from the get-go) do we see people bending over backwards to make sense of nonsense.

I am afraid we are getting sidetracked (that’s also my fault). I read the OP as being about whether we should believe that certain events took or not place in the ancient world which we call “miracles” today. I.e. if the ax-head floated or if Jesus rose from the dead, so that the question was not if God caused the ax-head to float but if the ax-head floated.. that’s a matter of what Ehrman meant by “miracle” so let’s just go with your definition and say it isn’t a miracle unless a God-like creature caused it to happen via some kind of violation of the laws of nature.

I don’t disagree with you that we can and should conclude that the stories of miracles (whether by Jesus, Sai-Baba or Vespasian) are not true, but I think there are reasonable objections to the argument on the many-world semantic. For instance I think many philosophers, including many atheistic philosophers, would say that you use a too narrow definition of “possible world” if you exclude a world with a God-like creature.

Tim H.: “. . . if you exclude a world with a God-like creature.”

I’m not sure what all you mean by that. To a primitive person, you would appear “god-like.” But you wouldn’t be capable of suspending the laws of physics.

To a naive person, a magician sawing a lady in half would have “appeared” to have performed a miracle. But I assume we all believe that apparent miracles are possible. Is anyone seriously debating that point? The only debate is whether actual miracles occur.

Ehrman differentiates between miracles as understood by modern people versus miracles as understood by people living in ancient times. Suffice it to say that today when people use the term miracle, they generally mean “supernatural violations of natural law, divine interventions into the natural course of events.” (Ehrman, 1999, p. 193)

Since he believes historians have no access to the supernatural, he argues that miracles are “problematic.” I contend that they’re only problematic if you worry about insulting people who adhere to a religion that still exists. If we were talking about magical dung beetles in ancient Egypt, nobody would have a problem with saying, “Oh, that never happened.”

http://vridar.org/2012/03/16/miracles-and-historical-method/

To clarify, by “. . . a world with a God-like creature.” I mean exactly the term you used in the Ehrman quote, “supernatural violations of natural law, divine interventions into the natural course of events.”.

Do I understand your argument in the OP correctly that you are saying that there are no possible worlds where there can be “supernatural violations of natural law, divine interventions into the natural course of events.”?.

About the floating axe head–there’s a possible world where the axe head hovers on the surface of the water _as if_ floating, but I think it’s right to say it’s logically impossible for the axe head to actually _float_ on the surface of the water. Floating necessarily involves comparative densities etc and once you’ve got an axe head hovering right at the surface of a body of water, all that is out the window. Whatever it’s doing, it’s not floating.

>A miracle is not a simple parlor trick; it is the suspension or reversal of known physical laws. In Christianity, the belief in miracles has everything to do with the belief that God.

Very Well said i think the problem with the figure of JC’s is that its soo neck deep in supernatural aura that you just cant separate miracles from his supposed life because if you do then there’s nothing left , For example In my free time i once tried to remove all miraculous instances and Future predictions found in KJV Mark and guess what the end result was only 5-6 pages long unconvincing story.

Excellent article, and very informative. Thanks.

It’s such a good argument that you put forth, I don’t see any strong refutation to it from theists. Even IF we granted god’s existence (if he’s perfect, he exists in a possible world. if he exists in a possible world he exits in all possible worlds etc.), he wouldn’t be able to work miracles in ANY possible world, which brings us back round to the Euthyphro dilemma!

There are possible worlds where UNC classes are fictional that include this world. Perhaps Ehrman has to deal with that issue on such a daily basis that the miraculous passing grades athletes get at UNC make him open to things like water-walking and iron floating.

Dr. James McGrath’s “MYTHICIST RIDDLE:” Why is mythicism just as fundamentalist as fundamentalist Christrianity?

Can you find the answer to the riddle below (Carrier vs. McGrath)? For a hint to solving the riddle, see the book “Man, Myth, Messiah (2016),” by Dr. Rice Broocks, pp. 141-170.

THE CLUES TO THE RIDDLE:

(1) Carrier points out on his blog that the Jesus stories could have been invented as a Scam. The Gospels seem to me to be written on two levels. On an everyday level, they contain lots of exciting miracle stories to “sell” Jesus to the masses. On another esoteric level, they contain a lot of scriptural intertextuality to make Jesus appeal to the learned class. Seneca famously pointed out that “religion is true to the masses, false to the wise, and useful to the rulers.” But what does this have to do with mythicism?

(2) From the first, the Jesus of mythicism is one of high Christology. In Mark we read Jesus describing himself in ways that go far beyond that of a normal, mortal man, where the focus is on atonement theology, not just Jesus being a traditional messiah trying to become king of the Jews: “31 And he began to teach them that the Son of Man must suffer many things and be rejected by the elders and the chief priests and the scribes and be killed, and after three days rise again (Mark 8:31).” Jesus taught that the Hebrew scriptures were fulfilled in him “today (see Luke 4:16-21).”

(3) The way for Jesus was prepared for Jesus by John the Baptist, a purely literary figure in the bible (whether or not there was an historical John the Baptist). The character of John the Baptist was created by the gospel writers as a hagaddic midrash on Malachi 4:5-6, and Isaiah 40:3-4. Building on this foundation of the midrash and intertextuality of John the Baptist, Mark says “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ ; AS IT IS WRITTEN IN THE PROPHETS.” Mark then immediately interprets John the Baptist as a forerunner of the Messiah (a la Elijah in II Kings 1:8). Mark then clothes John similar to Elijah (Mark 1:6. II Kings 1:8.) He then says John ate locusts and wild honey,the food of the wildernes in which Elijah lived (and so on and so on). John’s character is haggadic midrash through an through. Following this, as Price says, Jesus’ baptism by John is midrashic all the way down: The heavenly voice (bath qol) speaks a conflation of three scriptural passages. “You are my beloved son, in whom I am well pleased” (Mark 1:11) combines bits and pieces of Psalm 2:7, the divine coronation decree, “You are my son. Today I have begotten you;” Isaiah 42:1, the blessing on the returning Exiles, “Behold my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen, in whom my soul delights;” and Genesis 22:12 (LXX), where the heavenly voices bids Abraham to sacrifice his “beloved son.” And as William R. Stegner points out, Mark may have in mind a Targumic tradition whereby Isaac, bound on the altar, looks up into heaven and sees the heavens opened with angels and the Shekinah of God, a voice proclaiming, “Behold, two chosen ones, etc.” There is even the note that the willingness of Isaac to be slain may serve to atone for Israel’s sins. Here is abundant symbolism making Jesus king, servant, and atoning sacrifice. In view of parallels elsewhere between John and Jesus on the one hand and Elijah and Elisha on the other, some (Miller) also see in the Jordan baptism and the endowment with the spirit a repetition of 2 Kings 2, where, near the Jordan, Elijah bequeaths a double portion of his own miracle-working spirit to Elisha, who henceforth functions as his successor and superior. And, as Price further points out about the intertextuality of John the Baptist, Usually scholars allow some core of historical reporting to underlie the story of the Baptizer’s death (though any reading of Mark must be harmonized with some difficulty with Josephus), recognizing just a bit of biblical embellishment to the narrative. For instance, it is apparent to all that Herod Antipas’ words to his step-daughter, “Whatever you ask of me I will give it to you, up to half my kingdom,” comes from Esther 5:3. Herod’s painting himself into the corner of having to order the execution of his favorite prophet may come from Darius’ bamboozlement in the case of Daniel (Daniel 6:6-15) (Miller). But it is possible that the whole tale comes from literary sources. Price points out that MacDonald shows how the story of John’s martyrdom matches in all essentials the Odyssey’s story of the murder of Agamemnon (3:254-308: 4:512-547; 11:404-434), even to the point that both are told in the form of an analepsis or flashback. Herodias, like Queen Clytemnestra, left her husband, preferring his cousin: Antipas in the one case, Aegisthus in the other. This tryst was threatened, in Clytemnestra’s case, by the return of her husband from the Trojan War, in Herodias’, by the denunciations of John. In both cases, the wicked adulteress plots the death of the nuisance. Aegisthus hosted a banquet to celebrate Agamemnon’s return, just as Herod hosted a feast. During the festivities Agamemnon is slain, sprawling amid the dinner plates, and the Baptizer is beheaded, his head displayed on a serving platter. Homer foreshadows danger awaiting the returning Odysseus with the story of Agamemnon’s murder, while Mark anticipates Jesus’ own martyrdom with that of John. The only outstanding difference, of course, is that in Mark’s version, the role of Agamemnon has been split between Herodias’ rightful husband (Philip according to Mark; another Herod according to Josephus) and John the Baptizer.

John the Baptist was not the forerunner of and earthly king or leader, but rather the forerunner of the Lord Himself (see Luke 1:16-17). John denies that he is the Messiah himself, but proclaims that the lord will come after him (see John 1:19-20, 26-29).

(4) Jesus declared that he was the messiah (John 4:25-26). Unlike the prophets who spoke while saying “Thus says the Lord,” Jesus said “Truly I say to you,” to let the reader know that when Jesus was speaking the Lord was speaking. It was a high Christology through and through. Jesus taught with an authority only reserved for God. Jesus not only taught the Law of Moses, but felt he had the authority to upgrade it (see Matthew 5:21-22). He also felt he had the authority to forgive Sins (see Mark 2:1-12), an act that was only ever ascribed to God in the Hebrew tradition. No prophet ever claimed the ability to forgive sins except Jesus.

(5) Jesus truly was truly INVENTED as a dying/rising God by way of imitation and haggadic midrash. He was invented intertextually from The Suffering Servant of Isaiah 53:4-11. Some like Ehrman argue the Servant typology is meant to refer to “The Jewish People,” not a “messiah,” but Jesus in the gospels is portrayed as being a representative of the “type” of Israel (eg. Jesus was 40 days in the desert, like the Jews were 40 years in the wilderness; The Jews story has a Joseph, Jesus’ story has a Joseph, etc., etc.), so Isaiah 53 fits the Jesus story nicely. We also see the same thing happening with Jesus and Psalm 22. The story of Jesus’ birthplace was written as a midrash on Micha 5:2. The “piercing” of Jesus comes from Zechariah 12:10. The idea that Jesus was a king who was greater than all the kings of the earth comes from Isaiah 9:6-7. The timetable of Jesus in history (the crucifixion being around AD 30) comes from Daniel 9:25-27. Jesus has the descriptive title of The Son of Man (from Daniel 7:13-14). which would never be given to a mere man (let alone told from this that all nations would worship him). Jesus’ characterization as “The Son of God” is a midrash on Psalm 2:1-12. Jesus is characterized as equal with God and the same as God (see John 1:1-3, 14-18; John 8:56-59), and he is identified as the creator “see Colossians 1:15-17. John the Baptist prepared Jesus’ way while The Old Testament describes John’s “type” as preparing the way FOR GOD (Malachi 4: 5-6). Jesus described himself as The Good Shepard who would gather his sheep (see John 10:14-16), while the Old Testament uses the the same description for God (see Jeremiah 23:3). “Lord” is the same Hebrew word used for “God,” and Jesus is given this title in several New Testament passages. Paul calls Jesus “Lord (kyrios)” in Romans 10:9. Paul further associates this title with God in his citation of the Old Testament (see Romans 9:27-28). The earliest prayer of the Christian community uses the phrase “Maranatha,” which translates as “the (our) lord has come.” This phrase is Aramaic, so it probably originated with one of the earliest Christian communities. “Mar” has the same meaning as “kyrios,” and it is used in Old Testament passages to refer to God. The expression is also used in the Didache, which is a very early source. It is an expression that Paul uses (see 1 Corinthians 16:22), which occurs shortly after the early creedal formula in 1 Corinthians 15. This creed describes Jesus paying the Sin debt, which further reflects his divine nature. Ehrman and Carrier (unlike McGrath) argue there is a high Christology in Paul, and I would add it would make sense if this was present among all early Christians, since Paul knew the early church leader James, the brother of the Lord, and it would be odd if Paul and James had massively different Christologies since Paul never mentions anything about that.

(6) It is not surprising that the New Testament writers would invent the story of the resurrected Jesus, since they clearly had no problem with inventing wildly implausible resurrection stories AS THOUGH they were based on eye witness accounts. For example, in Matthew we read “51 At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom. The earth shook, the rocks split 52 and the tombs broke open. The bodies of many holy people who had died WERE RAISED TO LIFE. 53 They came out of the tombs … and went into the holy city AND APPEARED TO MANY PEOPLE (Matthew 27:50-54).”

So as I said at the beginning, Dr. James McGrath’s “MYTHICIST RIDDLE” is: Why is mythicism just as fundamentalist as fundamentalist Christrianity?

Can you find the answer to the riddle with the text I presented above (Carrier vs. McGrath)?

********As I said, for a hint to solving the riddle, see the book “Man, Myth, Messiah (2016),” by Dr. Rice Broocks, pp. 141-170.

lol

THIS SENTENCE FROM SECTION 5 SHOULD READ:

Jesus is characterized as equal with God and the same as God (see John 1:1-3, 14-18; John 8:56-59), and he is identified AS the creator (see Colossians 1:15-17).

John, explain to me what any of what you just wrote had to do with the original post, or I will block this wall of text.

Hi Tim. Sorry it has taken me so long to get back to you, but my health is not very good and I can’t get to the computer as much as I would like. As for my post, I just read your post about McGrath and I started thinking about how he likens mythicism to be the intellectual equivalent of young earth creationism, so I just wrote about that. Sorry if I went to far off topic. I will be more careful in the future. I enjoy blogging here at Vridar and didn’t mean to cause a problem.

No worries.

Actually it can, provided it displaces enough water to offset its weight (Archimedes’s Principle). A famous example was given by the “ironclad” ships used in the American Civil War.

(Not quite sure what the density of copper has to do with it, though).

I can’t remember why I noted the density of copper. It must have seemed interesting to me at the time.

Ships made of iron or steel float because their average density is less than the density of water. The overall density of an aircraft carrier is not 7.87 grams per cc. If it were, it would sink. Any object with a mean density greater than water will sink.

Here’s a fun page that explains buoyancy, upthrust, average density and why big metal ships float.

http://www.explainthatstuff.com/how-ships-work.html

[quote]Any object with a mean density greater than water will sink[/quote]

While it’s true that all objects with a lower density will float, this is only a sufficient condition, not a necessary one. So the above statement is not correct.

The only factor that matters is the weight of the water displaced by the object. (The physical explanation is that, before the object enters the water, the water where it’s about to go is pushing down on the water below it, because of gravity, and the water below it is pushing back, to resist compression, with a force which is just sufficient to counter the weight of the water above it. When the object enters and displaces the water above, the water below doesn’t “know” that the water above it is gone and continues to push with the same force.)

Any object that has a lower mean density will float, because the force from the water below pushing it upwards has to be greater than its own weight pulling it downwards.

However it is possible for an object with a higher mean density to float, if it can displace an equal or greater weight of water. (Physically speaking, the more water there was above, the more water there will be pushing back from below to support the object).

In principle, any object can be made to float, no matter how high its mean density, by making it flat enough and wide enough.

For example, people can float on the Dead Sea when lying down but not when standing up, because a prone torso displaces enough water, while a pair of feet doesn’t. (Biblical aside: I wonder if any apologists have tried to explain Jesus walking on the water by a temporary local increase in the density of water? Or maybe he was just wearing a giant pair of flippers?)

A solid iron ship would be extremely short, extremely wide and completely impractical. In practice, ship builders make the average density of their ships well below that of water by including plenty of air, which has a very low density. This allows them to produce a useful shape but has the disadvantage that anything which raises the mean density above the intended level, such as overloading with cargo or water getting into the hull, has a significant impact on buoyancy and increases the risk of sinking.

To sum up: saying that say that ships float because they have a lower average density than water is correct but does not give the full story about flotation. (On reflection, this may not have been the best example of the point I was trying to make). However, saying that any object with a higher average density must sink is not correct.

Obligatory wikipedia reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buoyancy