We often hear it said that historians deal with probabilities, not certainties. Thus Bart Ehrman explains in his latest book:

Historians, of course, can ask what probably happened in the past, for example, in the earthly ministry of Jesus with his disciples. And historians can establish with relative levels of probability that this, that, or the other tradition is likely something that happened or didn’t happen. But history is all a matter of such greater or lesser probabilities. When dealing with a figure such as Jesus, these probabilities are established only by critically examining the memories that were recorded by later authors.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 31). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. [My bolded emphasis in all quotations.]

Interestingly Ehrman assumes as a certainty (not probability) that the gospel narratives were sourced from “memories” of Jesus (whether personally experienced or fabricated memories) and sidesteps an entire area of biblical scholarship that argues the evangelists themselves imaginatively created the narratives of Jesus inspired by analogous tales in the Jewish Scriptures and other writings. He also uses the language — e.g. “that were recorded by” — we associate with historical “reports” or “records” thus further entrenching his bias in the mind of the reader. But we’ll leave Ehrman’s own contradictions aside for now and focus on the more general principle.

Anyone who has read scholarly works relating to Christian origins is familiar with the language of probability, possibility, maybe, likelihood, etc. Too often, however, this same language magically transforms itself as the argument proceeds into certainty. As Jacob Neusner in Rabbinic Literature and the New Testament complained of “pseudocritical” scholarship, it is commonly characterized a number of faults including

the use of “presumably,” “must” or “may have been,” and “perhaps,” a few sentences later magically converted into “was” and “certainly.” (p. 88)

A serious possibility

Let’s start with the reverse of history: forecasting the future. The past is past and gone but reverse our perspective for a moment and problems with vague and loose language become immediately obvious. The following cases are taken from Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction by Philip E. Tetlock and Dan Gardner. In early 1951 the CIA published a National Intelligence Estimate warning that a Soviet Union attack on Yugoslavia “should be considered a serious possibility.” What does that phrase mean to you?

But a few days later, Kent was chatting with a senior State Department official who casually asked, “By the way, what did you people mean by the expression ‘serious possibility’? What kind of odds did you have in mind?” Kent said he was pessimistic. He felt the odds were about 65 to 35 in favor of an attack. The official was startled. He and his colleagues had taken “serious possibility” to mean much lower odds. Disturbed, Kent went back to his team. They had all agreed to use “serious possibility” in the NIE so Kent asked each person, in turn, what he thought it meant. One analyst said it meant odds of about 80 to 20, or four times more likely than not that there would be an invasion. Another thought it meant odds of 20 to 80— exactly the opposite. Other answers were scattered between those extremes.

Tetlock, Philip; Gardner, Dan (2015-09-24). Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (Kindle Locations 858-864). Random House. Kindle Edition.

A fair chance

When in 1961 President Kennedy sought to know the chance a small army of Cuban expatriates landing at the Bay of Pigs would have in toppling Fidel Castro his Chiefs of Staff concluded that the plan had a “fair chance” of success.

The man who wrote the words “fair chance” later said he had in mind odds of 3 to 1 against success. But Kennedy was never told precisely what “fair chance” meant and, not unreasonably, he took it to be a much more positive assessment.

Tetlock, Philip; Gardner, Dan (2015-09-24). Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (Kindle Locations 872-873). Random House. Kindle Edition.

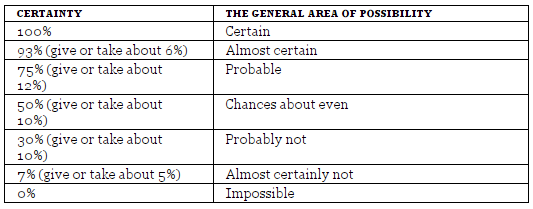

Sherman Kent of the CIA’s Office of National Estimates sought a remedy by setting out more precise meanings:

But the chart was never adopted.

Objections to using numbers

People liked clarity and precision in principle but when it came time to make clear and precise forecasts they weren’t so keen on numbers.

- Some said it felt unnatural or awkward, which it does when you’ve spent a lifetime using vague language, but that’s a weak argument against change.

- Others expressed an aesthetic revulsion. Language has its own poetry, they felt, and it’s tacky to talk explicitly about numerical odds. It makes you sound like a bookie. Kent wasn’t impressed. “I’d rather be a bookie than a goddamn poet,” was his legendary response.

Tetlock, Philip; Gardner, Dan (2015-09-24). Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (Kindle Locations 890-894). Random House. Kindle Edition. (My own formatting in all quotations)

Of course numbers can give a false impression of certainty and exactness where neither is possible.

[Y]ou cannot convert vague and dubious approximations (not to speak of nonsense and half-truths) into a mathematical science simply by transcribing them into the symbolism of mathematics. (Stanislav Andreski, Social Sciences As Sorcery, 131)

But there remains an honest use of numbers:

A more serious objection— then and now— is that expressing a probability estimate with a number may imply to the reader that it is an objective fact, not the subjective judgment it is. That is a danger. But the answer is not to do away with numbers. It’s to inform readers that numbers, just like words, only express estimates— opinions— and nothing more.

Similarly, it might be argued that the precision of a number implicitly says “the forecaster knows with exactitude that this number is right.” But that’s not intended and shouldn’t be inferred.

Also, bear in mind that words like “serious possibility” suggest the same thing numbers do, the only real difference being that numbers make it explicit, reducing the risk of confusion.

And they have another benefit: vague thoughts are easily expressed with vague language but when forecasters are forced to translate terms like “serious possibility” into numbers, they have to think carefully about how they are thinking, a process known as metacognition. Forecasters who practice get better at distinguishing finer degrees of uncertainty, just as artists get better at distinguishing subtler shades of gray.

Tetlock, Philip; Gardner, Dan (2015-09-24). Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (Kindle Locations 895-903). Random House. Kindle Edition.

Then there is the question of accountability and what Tetlock labels “the wrong-side-of-maybe fallacy.” It is easy to conclude that the weather forecaster was wrong if she said there was a 70% chance of rain and it didn’t rain but of course she was not wrong. Or at least we cannot tell from just one forecast like that. The only way to know if the forecaster is accurate is if we took a hundred occasions on which she predicted a 70% chance of rain and saw that it rained on around 70 of those 100 days. It is very easy to fallaciously assume that a probability figure has been proved wrong. So no wonder elastic language is so widely preferred:

So what’s the safe thing to do? Stick with elastic language. Forecasters who use “a fair chance” and “a serious possibility” can even make the wrong-side-of-maybe fallacy work for them: If the event happens, “a fair chance” can retroactively be stretched to mean something considerably bigger than 50%— so the forecaster nailed it. If it doesn’t happen, it can be shrunk to something much smaller than 50%— and again the forecaster nailed it. With perverse incentives like these, it’s no wonder people prefer rubbery words over firm numbers.

Tetlock, Philip; Gardner, Dan (2015-09-24). Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (Kindle Locations 917-921). Random House. Kindle Edition.

Tetlock and Gardner inform us that the Office of National Estimate’s move to using numbers only gathered pace “after the debacle over Saddam Hussein’s supposed weapons of mass destruction, and the wholesale reforms that followed”.

When CIA analysts told President Obama they were “70%” or “90%” sure the mystery man in a Pakistani compound was Osama bin Laden, it was a small, posthumous triumph for Sherman Kent. In some other fields, numbers have become standard. “Slight chance of showers” has given way to “30% chance of showers” in weather forecasts. But hopelessly vague language is still so common, particularly in the media, that we rarely notice how vacuous it is. It just slips by.

Tetlock, Philip; Gardner, Dan (2015-09-24). Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (Kindle Locations 925-928). Random House. Kindle Edition.

Hopelessly vague language is also common in historical studies of early Christianity. Let’s look again at those opening two quotations from Ehrman and Neusner:

Historians, of course, can ask what probably happened in the past, for example, in the earthly ministry of Jesus with his disciples. And historians can establish with relative levels of probability that this, that, or the other tradition is likely something that happened or didn’t happen. But history is all a matter of such greater or lesser probabilities. When dealing with a figure such as Jesus, these probabilities are established only by critically examining the memories that were recorded by later authors.

and

the use of “presumably,” “must” or “may have been,” and “perhaps,” a few sentences later magically converted into “was” and “certainly.”

Now compare these words with another passage from Ehrman also in Jesus Before the Gospels:

And so, for example, in what context would stories emerge about Jesus’s conflicts with the Pharisees, ending in a clever one-liner? Probably in a context where the Christians themselves were being confronted by non-Christian Jews, over their refusal, for example, to keep the Jewish laws of Sabbath. Since such stories show how Jesus bested the Pharisees on such issues, they would provide a sanction for the behavior of Christians decades later. Or in what context would stories of Jesus healing the sick or raising the dead emerge? Probably in contexts where Christians were trying to prove to outsiders that Jesus was the Son of God who had come in fulfillment of the prophecies of the healing power of the coming messiah. These stories, in other words, are not so much about Jesus as they are about the community that was telling the stories.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 48). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

“Would” indicates a mind-game, an imaginary historical scenario for which we have no evidence. “Probably” indicates a guess that is based on what we imagine would be happening in our imaginary scenario. “Are about” and “was telling” are unambiguous definite statements that we can “know”. See how the magic works.

Now Ehrman might be able to provide clear rationales for his conclusion in a work directed to a more scholarly audience but the point is that he has failed to do so here he has let his readers down.

Contrast the works of Richard Carrier. Proving history : Bayes’s theorem and the quest for the historical Jesus is like Tetlock and Gardner’s Superforecasting in which the argument for clearer thought and argumentation is presented. On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt is a demonstration of how to apply clearer argumentation that moves beyond the vague language that has long served the academy so well.

Neusner refers to “magic”. It really should be a mystery to everyone how such mind-games and guesses can pass as serious works of “history”. Carrier’s promotion of explicitly using Bayesian analysis is a genuine (and giant) step forward.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Ehrman’s language can be quite elastic. An event can be plausible in one paragraph, only to become something that “must have” happened in the next.

This sort of exercise has nothing to do with historical inquiry. It is bizarre make-believe scenarios built upon and elaborating the fundamental yet unsupported premise. I once compared how genuine historical inquiry into the development of social memory works: Tales of Jesus and Moses: Two Ways to Apply Social Memory in Historical Studies.

Suppose you had to give a modern account as to how Julius Caesar overcame Pompey and took control of

Italy. If you just look at the facts of the situation: Pompey had most of the Senate/Populace/Army behind

me him and Caesar was violating the laws of the Republic, in fact was declared an enemy of the Republic.

How in the world can Caesar drive Pompey out of Italy and eventually to a death by beheading in Egypt

a few years later ?

Now suppose most of those historical facts are missing from your account.

Yet you know, or at least believe that Caesar drove Pompey out of Italy, then out of Greece

and finally to Egypt…or was this a myth made up by Octavian to justify his becoming Caesar,

even though he, himself, was no great general. Octavian must have had all the histories of Rome

re-written once he became Emperor…in fact he was the illegitimate son of Antony who never suspected

his own son would hunt him and Cleopatra down in Egypt…and even kill his second cousin, Caesarea…

in double fact, Octavian arranged with his true father – Antony to have Julius Caesar assassinated.

If Jesus is a myth, then how do you explain Peter, Paul, James and John convincing contemporaries

of the mythical Jesus to convert to Christianity and why did the Jews persecute a sect based on

an imaginary man ? Jews accounts of Jesus and prayers agains the followers of the Nazarean

never deny that Jesus existed, only that He was not the Messiah.

Tim, you were not there, neither was I, but this type of pseudo- scholarship is sad in that it ignores a

simple truth – Jesus lived, His life influenced the Apostles and the Jews fought against it to the bitter

end, but they lost out.

How do you account for millions of Greeks believing in Zeus? By your argument, obviously Zeus must have been a real being.

We are not discussing whether Jesus was divine.

Just whether there is enough historical evidence to say that He lived.

The example of Zeus shows that often an obviously mythical being was taken as real. The fact that many believed in someone, does not prove that he existed.

“If Jesus is a myth, then how do you explain Peter, Paul, James and John convincing contemporaries

of the mythical Jesus to convert to Christianity and why did the Jews persecute a sect based on

an imaginary man?”

The same way Mormons converted thousands of followers based on the testimony of Joseph Smith. The same way Muslims converted billions based on the testimony of Mohammad.

But if you want to know what Paul actually converted people TO, reading his letters in their actual, pre-Gospel context tells you that apparently none of his converts needed any direct evidence; they seemed to be content with the visions of the apostles and hidden codes in the Old Testament. The life of Jesus, human being, was apparently of no concern, to Paul or anyone he was writing to. How did he do it? He must have been an extraordinarily persuasive man, but there have been others at least as persuasive, with evidence at least as poor, who have been arguably even more successful.

You miss the point.

Discussing whether Jesus lived or not.

Not His divinity.

You are the one who has introduced Jesus’s messiahship and divinity in your first comment. You fault us for not trusting documents that are primarily dedicated to persuading us to believe Jesus was the Christ and Son of God. (And you avoid my challenge to examine for yourself those other documents supposedly referring to Christians or Jesus.) It is clear that the question and methods used to answer it are only important to you because they are fundamental to your religious belief system.

Neil,

Can you please point out where I introduce Jesus’s messiahship and divinity in my first post ?

My inquiry and remarks are whether one should, as a historian, say there

is evidence, sufficient evidence in one’s view, to say that a man named

Jesus lived in first century Palestine, who was later said, by His followers

to be the Christ.

Yes. Here, in your first comment:

This is the standard apologetic argument used to “prove” Jesus was resurrected. I am sure you don’t mean to suggest that the apostles endured persecution because they believed Jesus existed as a historical figure. Of course not. You are implying that they suffered because of their beliefs about the divine identity of that person.

Then you conclude with:

You give away your entirely religious interest in the historicity of Jesus in that last line. It is clear that for you the historicity of Jesus is a matter of religious faith. It is based on believing religious texts telling you to believe that God entered history in the man Jesus.

You seem to be very reluctant indeed to bother responding to my answers to your questions there.

Again you have ignored my responses. So I’ll ask again: Do you think historians should take any literature at of any kind at face value to know what happened in the past? Do you think early Christian texts should be assessed any differently from any other ancient text before deciding what information they can reliably yield?

You replied to a much earlier post.

Any historian should look at all sources.

Then the historian has to decide which sources he

thinks are more important/more trustworthy and

write his history.

If you wish to write a history of Christianity in the

first century AD, examine every document you can find and weigh it in the balance of your judgement.

It would be fine if you explain why you take this text

more seriously than another and why you interpret the

text this way than that.

As for reliability, because we were not there,

we cannot speak reliably but only what we judge

to be the case or not.

I’m still waiting for you to engage with my response to your first comment.

What you say here about historical method is all truism. No one disagrees with any of it. So what, specifically, do you see as a fault with my arguments and methods? Do you know what my arguments and methods are? Or have you just come crashing in on assumptions and rumours of what you think I write? Please don’t repeat any of the appeals to incredulity in your previous comments — first engage with my responses to those appeals before repeating them. Or better still, try to engage with a particular fault you see with a particular claim or argument of mine. (i.e. stop trolling)

George, why do you bring up the question of mythicism here? Did you read the post? It is not about mythicism but something much more significant, a much larger question. (At least it is of more significance and broader relevance to anyone interested in the historical inquiry into Christian origins. Believers in a god-man Jesus will have other ideas but they don’t count as far as I’m concerned.)

But this once I will address your question though it does not conform to our comment policy that comments must be relevant to the post:

Your comment contravenes our comment guidelines by being irrelevant to the post. But I’ll address your points just this once more:

I addressed your previous comment and you are simply repeating some of the same arguments here. If you comment I think it is good form to read responses to your comments and engage with the arguments raised — don’t just repeat yourself and ignore the responses you get.

I have no evidence that Peter, James and John did convert anyone to “Christianity” — nor even Paul. The evidence i see before me indicates that there were people like Paul who led a certain sect within the panorama of Second Temple Judaism and that this sect over time came to distinguish itself more clearly from other Jewish sects. There is no evidence at all that prior to the fall of the Temple in 70 CE that anyone had any notion of a historical Jesus such as we read about in the gospels.

I don’t know of any evidence that Jews did persecute any such sect, at least prior to the second century. Paul himself said that he was personally attacked but that

was because he taught that the death of Jesus meant an end to the Law. Moreover, I think there were Jewish rivalries among certain sects but I don’t know what difference it would have made if some of them taught normal Second Temple Jewish ideas such as a heavenly Messiah figure who was an angelic or spirit being and only appeared in the form of a man.

You’ve evidently been reading a lot of apologetic propaganda. I invite you to take up the quest to actually see and read in translation the evidence for that Jewish prayer against the followers of “the Nazorean”. You might be surprised at what it actually says and how much certain apologists must read into it. As for your second assertion, what evidence are you relying upon exactly?

I trust you’ll attempt to seriously engage with some of the responses to your comments and are not here just to troll.

“I trust you’ll attempt to seriously engage with some of the responses to your comments and are not here just to troll.”

I doubt that very much. George Watson was banhammered from Cross Examined on Patheos after hundreds of comments of his unsupported nonsense being addressed without any rational engagement in discourse. The same off topic stuff he has posted here and more. Stuff that has been addressed ad nauseam, over and over again, c/w with links to some articles as evidence in support over here.

He has had the answers, but has decided to press reset and start fresh on a site he has not yet been excluded from commenting. I just hope that it was not my doing that led him here in the first place.

George is a troll to be sure, not really interested in any answers to his presuppositions. He is here to derail and his tactic’s include the Gish Gallop. BTW, he was a professor of Logic, Epistemology and Philosophy at THE top public uni in the U.S., among much more Walter Mitty claims, be warned.

The general question is what counts as Historical Evidence and do what degree can

we say it is probable that the events/persons claimed happened/existed.

If you wish to say that because you do not trust the Gospels, do not trust the Letters in the

New Testament, do not trust any Roman mention of Christians and do not think the Jewish

prayers and condemnations of Nazorean(s) really apply to Christians, then how do you explain

the spread of Christianity in the first century if Jesus did not live ?

Why do you ignore my reply to the first time you asked this question?

Do you really believe a historian should uncritically accept at face value all source materials and their versions of events?

Neil,

This is a reply to the longer reply you made at: 9:36 UTC.

If you wish to claim that no one was converted to being a follow of Jesus until

the temple was destroyed in 70 AD, you are very much in the minority among scholars,

which is fine but then it seems incumbent upon you to explain how Christianity arose

after the Temple was destroyed. You can suppose that once the authority of the Sadducees

ended with the destruction of the Temple and so whatever various forms of Judaism existed

were now free to find their own way without fearing behind brought to trial before the

High Priest, if you wish. Or you may choose to ignore trying to explain how the Church came

into existence after 70’s AD and just say: I can find no convincing historical evidence.

In that case, why don’t the writers of the Gospel/Paul just have Christ crucified weeks before

the rebellion against the Romans began and then tie in the destruction of Jerusalem to the

failure of the Jews to accept the Christ. Or move it to 132 AD just before the final rebellion.

Much tidier. Of course you don’t have to speculate on why they did not, just say:

I have no evidence.

But it is not that there is no evidence, but that you reject the evidence other accept, and one can rightly wonder, if a pristine Gospel and Trial Records of the High Priest and of Pilate were found

and dated to 35 AD, would you accept them as Historical or some ancient forgery or modern forgery

and if so why.

What power after the second rebellion did Jews have to persecute anyone ?

If, after the first rebellion the Jews no longer had a High Priest or King to try the brand new

Christians, why should Paul renounce the Law and say he was persecuted by the Jews – they

had know religious/civil power to do anything against Paul, let alone enforce the Law of God.

Why doesn’t Paul and others in the New Testament just say:

See the Leaders of the Jews handed Jesus over to the Romans, the Procurator did not want to crucify

Him, but he did so to please the High Priest and the mob.

Now God has destroyed Jerusalem and the Temple and the Law is no more…

You can ignore trying to answer those questions, but no serious scholar is going to take your

simple dismissal of Jesus/Paul/Peter/James, the trial and death of Jesus unless you can

answer questions along those lines.

It is rather as if all the copies of the Declaration of Independence were lost when the

British burned Washington and you are going around saying:

See, we don’t actually have the original Declaration, I see no evidence that it was written in

1776…if fact it is a product of Andrew Jackson…

The prayers against the Nazareans, and the Talmudic references have been attacked by those

who cannot bear the thought that Jesus lived. I will stand with the Jewish scholars who accept

that they refer to Jesus and Christians. However, if you wish to cite some sources for me to

read concerning them, I am willing to read them.

If you have any Ancient Jewish text that says explicitly that Jesus never lived

please let me know, as I have been asking people for one(s) for years.

I hope that I have answered the question you wanted asked.

I find the web-site somewhat confusing and have had a hard time finding your reply

and to which reply of mine your are making reference.

I wrote no such thing. Your reading comprehension is too lacking to have a reasonable conversation.

You have absolutely no idea of what I have written and argued about the evidence, do you. So why are you bothering to waste your time here? Nor do you have the slightest skill in mind-reading.

I see you do just absolutely love to concoct a lot of imaginary arguments that you think are genuine alternatives in my own thinking yet have not bothered to try to find out one single post where I explain my own views. You ignore my own comments and the links I have included in them to explain more detail and proceed to suggest I must be thinking any one of some other range of utter nonsense.

Goodbye, Mr Troll. Welcome to my spam list.

“… how do you explain Peter, Paul, James and John convincing contemporaries

of ‘the mythical Jesus’ to convert to Christianity” — How does Mormonism work? How does Islam work?

“and why did the Jews persecute a sect based on an imaginary man?” –perhaps they didn’t. Perhaps the persecutions are way overstated?

” Jews accounts of Jesus and prayers against the followers of the Nazarean never deny that Jesus existed, only that He was not the Messiah” Appeal to belief is a fallacy

“Contrast the works of Richard Carrier. Proving history : Bayes’s theorem and the quest for the historical Jesus is like Tetlock and Gardner’s Superforecasting in which the argument for clearer thought and argumentation is presented. On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt is a demonstration of how to apply clearer argumentation that moves beyond the vague language that has long served the academy so well.”

I have to disagree. In PH and OHJ Carrier is well aware of the benefits using probabilities could potentially give us (self-consistent ways of doing inference), however he ignores that those benefits assumes we have the *right* probabilities and the *right* logical structure of the propositions which we certainly do not. In addition, PH provides the reader with a very inaccurate picture of Bayesian probability theory. To give two examples from PH and OHJ:

1) The only serious application of Bayes theorem in PH is to the criteria of embarrassment. It is treated without a variable indicating if a text is actually embarrassing. I dare say this oversight is only possible when one decides to frame an otherwise simple intuition symbolically. It is also why Carrier concludes the criteria works in reverse and other treatments reverses that conclusion. So which is correct?

2) In OHJ Carriers use of reference classes in conjunction with the Rank-Raglan criteria is simply a textbook example of a fallacious statistical argument in which a method (reference classes) is applied in a manner obviously contrary to where it is applicable. The argument implies that given the four Gospels alone, Jesus almost certainly did not exist. There is a caricature of statisticians as people who ignores the real complexity of a problem in favor of a too simple model treated as objectively true, for instance the statistician who woke up after his wedding and wondered: “At this rate where will I make room for the other 7 women in a week?”. In treating the rank-raglan criteria Carrier is exactly arguing we should ignore all the historical details in the Gospel compilation and focus on their resemblance in some aspects to other documents which are very different.

This is also a good example of where Carrier believes that the use of Bayes theorem guarantee coherent results but appears not to be aware that reference classes violates Bayes theorem such that that result does not hold.

Did you read the book?

Ignoring the real complexity is exact opposite of what he does, which is probably the most complex case on historicity to date,

and Rank-Raglan criteria alone are hardly presented as sufficient to establish non-historicity.

Reference classes work fine, we don’t normally believe in existence of RR heroes, unless there’s some evidence to the contrary,

and this evidence is exactly what historicists fail to provide thus far.

Yes, I have read both books. I do not know if the books are the most complex case on historicity and my comments do not relate to the validity of the historical information found in the books (I am not the right person to ask). What I wrote in my post is that given the *Gospels alone* Jesus very likely did not exist (I believe it is about 6% chance he existed) according to OHJ.

Reference classes work well as an approximation in some cases, not so well in other. My claim is that the case Carrier considers is one where they do not work well. I agree most RR heroes do not exist, however the problem with such an argument is that it ignores the historical circumstances. For instance, most people mentioned in surviving Josepheus manuscripts do exist, so a similar prior computed based on that information alone would give Jesus almost certainly did exist. You can read arguments supporting these claims in my review you like.

Setting aside that we can’t be sure if Josephus mentioned him (and he most probably didn’t), notice that the first half of Antiquities deals almost exclusively with nonexistent people, some of them belonging to the RR class.

Anyway this objection is not valid, because even if we assigned the ‘mentioned by Josephus’ class probability close to 1, and included both that and RR, it wouldn’t affect the prior, because probabilities are multiplicative.

It has to be so, otherwise we could get insanely high prior in case of characters like Spiderman, by assigning them to the ‘people with names’ class.

That’s why we have to use the ‘comic book superheroes’ class in case of Spiderman, and the RR class in case of Jesus, possibly along with any other relevant classes.

Hi,

I am on my ipad so this will be brief. You are right probability theory in principle allowed any decomposition, but that result simply does not hold when one use reference Classes and assign probabilities from frequencies. If you believe otherwise, please just try to find any reference that proves the claim.

re spiderman, what we ought to do is use all available information. Reference Classes is throwing away information.

No, that’s not how it works.

Nothing is thrown away. Given the evidence is good enough, it can counter the prior.

Now RR is important information itself.

See, there’s no physical evidence, all we got is claims, so, the real question is, how credible are these claims?

What RR says, is that at the place and time people often claimed that fictitious characters with the specific set of attributes existed. This is indeed a relevant information, do you have any good reasons you choose to throw it away?

When you say nothing is thrown away, do you mean what we ought to do or what Carrier does?

I do not advocate ignoring the rank raglan information.

Can i ask you a question: do you believe that only given the gospels there is a 93% chance jesus did not exist?

Replying to the comment below, there’s no button there for some reason.

“Can i ask you a question: do you believe that only given the gospels there is a 93% chance jesus did not exist?”

That’s not what Carrier argues in the book.

He says that gospels have no effect on probability, and that I agree.

Most gospel information about JC is nonsense, so there’s no reason to believe in what’s left, therefore gospels provide no useful information.

On the other hand, if all we had were gospels, there would be no reason to consider historicity of a hypothetical man about whom nothing can be known for sure.

I agree Carrier says the Gospels have no effect on the probability Jesus existed, however if you follow his assumptions that’s not what actually argues. Just do the math, with the same symbols as in OHJ:

h : Jesus is historical (i.e. the scenario Carrier outlines)

~h : Jesus is not historical (i.e. the scenario Carrier outlines)

Gospels : Evidence of the gospels

Then Carrier assumes:

P(Gospels|h) = P(Gospels|~h)

in which case:

P(h|Gospels) = P(Gospels | h)P(h) / (P(Gospels | h)P(h) + P(Gospels | ~h)P(~h) ) = P(h) = 6.25%

I take it you do not agree with that conclusion?

No, I’m sure that’s not the case.

6,25% is the lower bound of the prior probability, the upper being 33%

Of course, if the gospels are irrelevant, then if you take into account only RR and the gospels, then the lower bound is 6,25%, but that’s not gospels alone, as you seem to interpret it.

However, you may have a point, even if it’s not how Carrier puts it,

because if we ignored the RR at the prior probability stage, then we’d be allowed to count the fact that the gospel character fits the RR class as evidence, and that would make gospels evidence against historicity, instead of being irrelevant.

Hi Zbykow,

6.25% is the most realistic estimate of the probability according to Carrier, 33% is the most absolutely most optimistic bound.

The probability I compute, P(~h|Gospels.b), *is* only based on the Gospels as evidence. According to Carrier, the RR class is supposed to be the *prior* probability and so this is correct use of terminology.

Asides that, how do we know that Jesus belongs to the RR reference class? To say that Jesus belongs to the Rank Raglan reference class is to say he was born of a virgin, that he was attempted murdered as a baby, that he meets a mysterious death, etc. etc. These things are known from the Gospels. So when we condition on the Gospels, we condition on the information that places Carrier in the RR reference class. Thus the 6.25% (or 33% as a most optimistic estimate) chance of Jesus existence appears directly implied in the text. Do you agree?

if we ignored the RR at the prior probability stage, then we’d be allowed to count the fact that the gospel character fits the RR class as evidence, and that would make gospels evidence against historicity, instead of being irrelevant.

Yes that’s what Carrier says but try to think about how that argument would have to run. We would have to say that all the biographical information the Gospels supposedly provides us about Jesus is irrelevant, however what is very relevant is that the Gospels says he is e.g. born of a virgin (along with the other pieces of information) and *those* facts strongly supports our claim Jesus was mythical to a certainty of 93.75%. So we have:

born of a virgin: Historically very significant.

Preaching work: Irrelevant.

Dies atop a hill: Very significant

Said to dine with friends: irrelevant

etc. etc.

“born of a virgin: Historically very significant.

Preaching work: Irrelevant.”

No, nobody says that claims of him being born of a virgin have any historical significance. In fact, we pretty much know he wasn’t, if he existed.

Historical significance of the claims is one thing, claims themselves another.

Historical Jesus is one thing, the gospel protagonist another.

Unlike the facts about the hypothetical historical Jesus, we can tell for sure what these claims say about the literary character, historical or not.

We are 100% sure, that the literary character JC as portrayed in the gospels belongs to the RR class.

Since we know that RR hero characters are usually fictional, then it follows that most likely there’s no historical figure behind the gospel stories, and nothing in them has any historical significance.

i

[i]i[/i]

No, nobody says that claims of him being born of a virgin have any historical significance. (…) We are 100% sure, that the literary character JC as portrayed in the gospels belongs to the RR class. [i.e. that he was born by a virgin among other things]

Since we know that RR hero characters are usually fictional, then it follows that most likely there’s no historical figure behind the gospel stories,

Okay I am a bit confused. According to you, the Gospels have little or no value in terms of establishing historicity. However you also appears(?) to agree with Carriers Rank-Raglan prior and so the conclusion implied in OHJ that conditional only on the Gospels the chance Jesus did not exist is most reasonably 93.25%? If not, could you tell what probability in the computation I showed you believe to be wrong? I can assure you they are all taken from OHJ.

We are 100% sure, that the literary character JC as portrayed in the gospels belongs to the RR class.

Since we know that RR hero characters are usually fictional, then it follows that most likely there’s no historical figure behind the gospel stories, and nothing in them has any historical significance.

We are also sure Jesus was a jew (and since most jews existed…) we are also sure Jesus is mentioned in our Josepheus manuscripts (and since most who are mentioned…) and so on and on.

Okay I am a bit confused. According to you, the Gospels have little or no value in terms of establishing historicity.

It was about historical significance.

Just like Spiderman comic books, they have virtually no historical significance, but they are strong evidence against historicity of Peter Parker, if you cared to undertake such an inquiry.

We are also sure Jesus was a jew (and since most jews existed…) we are also sure Jesus is mentioned in our Josepheus manuscripts (and since most who are mentioned…) and so on and on.

Not at all, we are not even close to being sure he was a Jew, since we can’t be sure he even existed.

We’re only sure that the literary character is claimed to be a Jew.

Then again, you are free to include as many relevant classes as you like, but generic classes lake that won’t improve your odds anyway.

Zbykow: I am not following you with Spiderman. So the Gospels are evidence against historicity?

I can’t help but noticing you did not address my questions in my previous post.

Then again, you are free to include as many relevant classes as you like, but generic classes lake that won’t improve your odds anyway.

Okay, but I am not interested in improving any odds. I am interested in how we ensure the use of other classes allows us to arrive at consistent results in practice. Say, suppose you begin with the “thought to be a jew”-class, then try to consider what probabilities you would have to assign to the gospels to arrive at consistent results.

“So the Gospels are evidence against historicity?”

In conjunction with our knowledge about the world and literature, yes they are.

“Say, suppose you begin with the “thought to be a jew”-class”

That would mean I failed to think of anything more specific and relevant to the problem, or that I really desired for the character to turn out to be historical.

Even take something like “A character from ancient religious literature said to be a Jew”. Not so obvious now huh?

Really, if you wanted to find out if Spiderman was historical, would the only class you could think of be “said to be an American”?

In conjunction with our knowledge about the world and literature, yes they are.

I.e. you agree that P(~h|Gospels.b) = 93.75% (according to our best estimates)?. I am just curious because it seems very counter-intuitive to me.

That would mean I failed to think of anything more specific and relevant to the problem, or that I really desired for the character to turn out to be historical.

But isn’t it a bit of an odd feature that you got so many classes to choose from (and based on what criteria?) and they all seems to require very careful arguments to arrive at the same result?

Really, if you wanted to find out if Spiderman was historical, would the only class you could think of be “said to be an American”?

I think you misunderstand my position. I do not agree that reference classes can be used in this manner because I believe you enviably end up violating the rules of probability theory, i.e. you are not being Bayesian. Please notice this is just the mainstream view in statistics, I do not think you can find any textbook which support this usage of reference classes contrary to the impression OHJ might leave one with.

“I.e. you agree that P(~h|Gospels.b) = 93.75% (according to our best estimates)?. I am just curious because it seems very counter-intuitive to me.”

What’s counter intuitive about that?

IMO the probability is about the same as in case of any other ancient literary supernatural being, so 93% seems to be within the range.

“But isn’t it a bit of an odd feature that you got so many classes to choose from (and based on what criteria?) and they all seems to require very careful arguments to arrive at the same result?”

No, the best class usually affects the result the most, if you use some generic classes along with RR, you still get about the same probability as if you used RR alone.

“I do not think you can find any textbook which support this usage of reference classes contrary to the impression OHJ might leave one with.”

Because it is very basic, the principle is used extensively e.g opinion polls, it’s just so obvious there’s no need to rediscover it every time it’s used.

Hi zbykow,

What’s counter intuitive about that?

IMO the probability is about the same as in case of any other ancient literary supernatural being, so 93% seems to be within the rang

Well, for starters I don’t see how it follows given only the Gospels that Jesus underwent a death burial and resurrection in the supernatural realm as is part of ~h. What you are saying is this is 93% certain given only the Gospels but I don’t think that probability is very intuitive.

No, the best class usually affects the result the most, if you use some generic classes along with RR, you still get about the same probability as if you used RR alone.

What does it mean to use a generic class alongside the RR?

Because it is very basic, the principle is used extensively e.g opinion polls, it’s just so obvious there’s no need to rediscover it every time it’s used.

The question put forth in polls are very simple (i.e. well-specified) and so simply counting the frequencies is quite accurate (I.e. you are interested in answering: “Given you only know a person is from the population in a given country, how would he or she answer this question”. I.e. you have very limited information).

That’s why I consider it quite different than what Carrier is doing. I don’t know how we can come to a sort of agreement on this issue. You seem to be of the opinion that the use of reference classes as Carrier use them is unproblematic and so common in statistics nobody would bat an eye; I believe it is so obviously asking for problems that it is highly controversial!. I suppose we could solve it by finding references in the literature that support our view. Here is one which discuss the problems of using reference classes:

http://philrsss.anu.edu.au/people-defaults/alanh/papers/rcp_your_problem_too.pdf

“for starters I don’t see how it follows given only the Gospels that Jesus underwent a death burial and resurrection in the supernatural realm”

You said you feel it’s counter intuitive that gospels are evidence for non historicity,

so please don’t redefine your problem in the middle of an argument.

Of course supernatural realm don’t necessarily follows from gospels, and we already are discussing the realm issue elsewhere.

“What does it mean to use a generic class alongside the RR?”

A subject may belong to more than one class. You can choose to include more than one and compute the probability the usual way.

“The question put forth in polls are very simple (i.e. well-specified) and so simply counting the frequencies is quite accurate”

Just as in our case. How many known members of the RR class are believed to be historical figures? Simple enough.

Any more evidence we got go elsewhere, and because of how BT works, given the evidence is strong enough we still could get a result way above the initial prior, possibly close to 1.

You said you feel it’s counter intuitive that gospels are evidence for non historicity,

so please don’t redefine your problem in the middle of an argument.

Of course supernatural realm don’t necessarily follows from gospels, and we already are discussing the realm issue elsewhere.

Right from the beginning I have been talking about Carriers hypothesis of mythicism ~h and all my questions/assertions has been about ~h. You may consider another idea about mythicism and it may be very plausible given only the Gospels, but this is not what I or Carrier discuss and we do not have the numbers in OHJ to talk about it. All there is to my point is that according to Carrier the probability of ~h given only the Gospels is 93% (p(~h | Gospels.b) = 93%) and ~h includes the information about death and burial in the supernatural realm. It seems we are in agreement that this number is worryingly high.

A subject may belong to more than one class. You can choose to include more than one and compute the probability the usual way.

You can take the union of two classes.. combining two classes otherwise does not appear immediately obvious to me.

Just as in our case. How many known members of the RR class are believed to be historical figures? Simple enough.

Any more evidence we got go elsewhere, and because of how BT works, given the evidence is strong enough we still could get a result way above the initial prior, possibly close to 1.

You misunderstand what I mean by simple. Take the case of P(Influenza|Fever). This is a simple case because the reference class is only those about which we know they have Fever. This is little information and there are many that matches all that information.

If we take Jesus then we have p(~h|b). But b is all our background information which Carrier spend about 100 pages to itemize. This is far from simple and so Carrier rather choose another reference class (The RR information). This brings us to the entire discussion about loss of information, approximations and so on and on. I would recommend you to try to work out what happens symbolically and perhaps give the article i linked a look.

“~h includes the information about death and burial in the supernatural realm.”

Yes it does, and RR does not, yet it’s still OK, because ~h still belongs to the RR class. RR is not the same thing as ~h and RR heroes need not all be identical.

“But b is all our background information which Carrier spend about 100 pages to itemize. This is far from simple and so Carrier rather choose another reference class (The RR information). This brings us to the entire discussion about loss of information”

Yes, that’s the idea, and your worries about loss of information are unjustified, since all information that’s left is accounted for elsewhere.

Try looking at the whole equation, instead of just a tiny part of it.

zbykow:

Yes it does, and RR does not, yet it’s still OK, because ~h still belongs to the RR class. RR is not the same thing as ~h and RR heroes need not all be identical.

Okay lets back up a moment. I hate to ask you the same question again and again, but I am honestly interested in your view and I feel you are avoiding the question:

Do you agree with the proposition that there is a 93.75% chance that ~h is true given only the Gospels [i.e. p(~h|Gospels.b) = 93.75% as is implied by OHJ]. That is, given only the gospels, there is a 93.75% chance Jesus underwent a death and resurrection in the supernatural realm?

Yes, that’s the idea, and your worries about loss of information are unjustified, since all information that’s left is accounted for elsewhere.

How do you know this? I.e. how do we prove this to someone who might doubt this is the case? I would invite you to re-write the probabilities in OHJ and see where that information is supposed to go.

“Do you agree with the proposition that there is a 93.75% chance that ~h is true given only the Gospels”

Once again:

1. Nobody but you says that (given ~h is as it stands in OHJ)

2. Yes it’s within range (given ~h is as it stands in PH)

3. Yes it’s within range, if you asked about ‘not h’

“How do you know this? I.e. how do we prove this to someone who might doubt this is the case?”

I’d encourage him to read the book.

All information left goes in P(e|h.b) and P(e|~h.b)

So to paraphrase your response, yes, you agree with the proposition that

P(~h|Gospels.h) = 93.75% (using our most plausible estimates)

where ~h includes the proposition that Jesus underwent death and burial in heaven?. I.e. that there is (at least) a 93.75% that Jesus underwent death and burial in heaven given only the Gospels?

I agree in a trivial sense that “I am the only one who says that”. However I showed how it follows from Carriers assumptions symbolically above; if you believe there is an error please point it out and I will happily acknowledge to be wrong. It is like if i say that a=3 and b=4 then i have not strictly speaking said that a+b=7, however it is certainly implied.

I’d encourage him to read the book.

All information left goes in P(e|h.b) and P(e|~h.b)

Not if we replace all the information in b with a lesser set of information (the RR information). Carrier newer proves this in OHJ and with good reasons. If you are interested, i could show you the computation?

No, that’s the opposite of what I wrote.

It also doesn’t follow from Carrier’s assumptions. In your example it follows from both gospels and his argument that the only significant version of non-historicity is ~h which comes from elsewhere.

That’s not gospels alone.

“Not if we replace all the information in b with a lesser set of information (the RR information).”

But we don’t.

RR is only used to compute the prior, all evidence is still weighed using all of b minus RR.

Zbykow: Okay, so what we have so far is:

1) It cannot be concluded that p(~H | Gospels.h) = 93.75% based on OHJ and in fact this is quite plausibly not true

2) It is however formally true (by simple computation, see above) that we can derive p(~h|Gospels.h) = 93.75% by applying Bayes to the numbers given in OHJ (that’s what I did above)

3) This is explained by there being some kind of formal (or at least syntactical) inaccuracy in OHJ which allows us to derive a false result, i.e. the “only significant version of non-historicity” argument.

It seems like we agree on 1 and 2, 3 is my attempt to restate what you wrote.

RR is only used to compute the prior, all evidence is still weighed using all of b minus RR.

I’m trying to work out what alternative decomposition you have in mind and I am not quite following you. Would you mind writing out what computation you have in mind?

What really goes on is this:

~H – Jesus is a mythical person historicized

~h – the usual supernatural realm etc..

What he does for the most part, is bayesian reasoning for H/~H

then he argues that ~h is the only valid version of ~H

However, in the book it appears in reverse order, hence the confusion.

Yes, he could put it better and make distinction between the two, but once you understand the argument, it doesn’t affect the conclusions.

Zbykow:

Well, saying that the symbols mean something else than how they are defined in OHJ makes it a bit hard for me to follow the conversation because I got the impression Carrier used the same definition of ~h throughout the book.. Perhaps I can ask him this on his blog.

The central issue remains, I think, that p(~h|b) != p(~H|b) because ~h contains more elements than ~H. So what probability is it that we compute? If we change between ~h and ~H when discussing the prior and the probability of the evidence, we still need to compute the probability of ~h to account for the difference. I don’t see anything in the text to suggest how this is supposed to be done.

“I got the impression Carrier used the same definition of ~h throughout the book.”

Yes but in 3.3 he also says that technically ~h should be ~H.

If you don’t agree with his reasons why they are about the same, for you it just becomes ~H and you can stop loosing sleep about that supernatural realm.

“The central issue remains, I think, that p(~h|b) != p(~H|b)”

These are just prior probabilities, they could be different, but in this case they’re equal, because they use the same reference class.

If you were making the argument, you could choose different.

If you really want something to be different, technically it’s P(~H|e.b) greater or equal than P(~h|e.b)

but remember we work with estimates, don’t try too hard making it into exact science.

Hi again Zbykow,

Yes but in 3.3 he also says that technically ~h should be ~H.

This is not the reading I get from 3.3. The way I read Carrier is that he defines ~h as including e.g. the burial and resurrection in the supernatural realm and then consistently use ~h throughout the book. 3.3 acknowledges that ~h is a subset of ~H, however he also argues that this can be ignored (based on an argument that I consider to be plainly faulty) and then proceeds with just using ~h in the subsequent chapters.

To take up a previous thread, I am still not absolutely clear where you stand with regards to the result

p(~h | Gospels.b) = 93.75%.

Which I have mentioned many times (see above). We seem to agree it follows (symbolically) from the assumptions made in OHJ and that, as it stands, do not conform to our intuitive judgement. However do I understand you correct to be saying that this result should really saying:

p(~H | Gospels.b) = 93.75%?

Because Carrier, at some point during OHJ, was imprecise in which probabilities represents ~h and ~H?

If you don’t agree with his reasons why they are about the same, for you it just becomes ~H and you can stop loosing sleep about that supernatural realm.

But I think it matters greatly if we use ~h or ~H in terms of the overall argument. Are you saying that it makes no difference in terms of explaining the evidence if ~h is replaced by ~H? I.e. that is it equally easy to explain e.g. the Gospels if we simply assume Jesus did not exist (~H) as it is if we assume Jesus did not exist but subsequent Christians came to believe or taught Jesus DID exist? (~h)?

Suppose you have two groups of people. About one group, you are told they simply don’t believe Muhammed exist, and about the other group you are told they believe Muhammed does exist or at least wish to teach this.

Over the next couple of decades, which of these two groups do you think are more likely to write something that resembles historical tales about Muhammed? (i.e. the Gospels)? The group about whom you don’t know if they believe Muhammed exists, or the group about which you know that they believe Muhammed exists?

We can raise the same question about the other more specific criteria which are part of ~h. For instance, if we assume a group teaches or believes Jesus died and was resurrected in the supernatural realm, whereas for another group we are not told such a thing, which group do you think more plausibly will leave behind stories like those of Paul where Jesus undergoes a form of death and resurrection?

If you really want something to be different, technically it’s P(~H|e.b) greater or equal than P(~h|e.b)

Indeed! And by the same logic, it is p(P5|b) greater than or equal to p(~h|b) = 93.75%. This alone does not teach us much except that we need to establish the probability of ~h since it may differ from ~H.

Look, I think many times in this argument you are more critical of what I say but accept what Carrier says and re-phrase it as statistical arguments; that’s understandable since I am a random person on the internet and Carrier has at least published one book which discusses Bayes. However I see these issues as quite black-and-white and Carriers argument for why what he does works (like why we can use ~h rather than ~H in 3.3) as very plainly falling apart when they are translated back into statements about probabilities. This is also why I think Carrier chooses to phrase these arguments in words and not using probabilities; something which is quite odd since the central argument in PH is that arguments should be stated using probabilities.

I implore you to go over these arguments, try to phrase them symbolically and see if they can indeed be made to work. When Carrier for instance says that the information not being used in the RR reference class “goes elsewhere” (a sentiment I believe you accept), try to work out what that actually means symbolically using the product rule. Wherefrom does the RR criteria information come and whereto does the background information not part of the RR criteria go? It isn’t exactly pretty and it is certainly not simple.

Just a last thought. I think we are discussing something about which it seems we both agree there is an objective truth. If you take the issues we have discussed in this thread, what would at this point convince you of one of the points I have made?

“Are you saying that it makes no difference in terms of explaining the evidence if ~h is replaced by ~H?”

In this case yes, because every argument in favor of non-historicity he makes is compatible with both. Your best bet would be to try and find some evidence expected on ~H but not on ~h.

“I.e. that is it equally easy to explain e.g. the Gospels if we simply assume Jesus did not exist (~H) as it is if we assume Jesus did not exist but subsequent Christians came to believe or taught Jesus DID exist? (~h)?”

If you put it this way they’d be exactly same thing, because “subsequent…” is already a part of background knowledge.

Also note that on ~h both subsequent and precedent communities believed or taught he did exist. They only disagreed on the nature of this existence.

You seem to be missing this point in your Muhammad example.

“And by the same logic, it is p(P5|b) greater than or equal to p(~h|b) = 93.75%. This alone does not teach us much except that we need to establish the probability of ~h since it may differ from ~H.”

You overestimate the significance of P5. It’s a given and IMO it shouldn’t even be a part of the hypothesis, but if it is it doesn’t hurt.

P5 is not the reason why ~h and ~H are not the same, P1-P4 are.

As to the 93% question, you seem to be unsatisfied with my answers so far and I can’t help it. Why don’t you just say what bothers you about it?

“Are you saying that it makes no difference in terms of explaining the evidence if ~h is replaced by ~H?”

In this case yes, because every argument in favor of non-historicity he makes is compatible with both. Your best bet would be to try and find some evidence expected on ~H but not on ~h.

“I.e. that is it equally easy to explain e.g. the Gospels if we simply assume Jesus did not exist (~H) as it is if we assume Jesus did not exist but subsequent Christians came to believe or taught Jesus DID exist? (~h)?”

If you put it this way they’d be exactly same thing, because “subsequent…” is already a part of background knowledge.

I think we are talking past each other. I realize for the most part I keep pointing at isolated aspects of the argument (“look! ~h is not ~H”) and you keep giving reasons why these isolated problems can be fixed with additional assumptions (i.e. “subsequent…” is part of our background knowledge). Then I say: “Yes, but in that case …” and around it goes. I am sure you also find this a bit frustrating :-).

If you look at my review, I have discussed most of the things we have brought up. For instance, the proposal that there are “things” in our background knowledge that guarantees the additional elements in ~h (compared to ~H), such as Jesus being crucified and burried in the supernatural realm, is discussed in my review of OHJ from p23 bottom to p27. I 100% agree we can easily think about something in our background knowledge that would do that!

The central claim in my review is not that each and every of these additional assumptions in and by themselves and strictly speaking are wrong, but when you look at the various assumptions together things break in a major way.

How does this happen in this case? Well, it is quite easy. You suggest in your above response that there is information in b such that the additional elements in ~h (compared to ~H) becomes exceedingly plausible. For instance, suppose we could add to b the information:

C1 : “later church tradition about an earthly Jesus”

(In this case there is an issue about the timing here, namely what “later” means. I take it that “later” means sometimes around the time of the Gospel compilation, that is within 50 years of the “supernatural Jesus” tradition found in Paul (according to Carrier).

Similarly, we can add other elements to our background knowledge that guarantees the other parts of ~h over ~H. Lets call all these parts C and then we have that b is composed of C and some other background information B. I.e.

b = B . C.

Then, conditional on b (which contains C) it is true that subsequent christians came to believe (or at least teach) that Jesus had an earthly existence. It’s trivially true now!

So why do I keep complaining? Well, if we take Bayes theorem seriously we have to take serious the assumptions it build upon. That means that when we add information to b (such as C) we have to be able to account for where that information goes in subsequent computations. In my review (p.24), I provide an example of how (seemingly) trivial information added to our background knowledge can dramatically affect our conclusions . That’s why I advocate we should be careful and not just rely on our intuitive judgement but actual computations and very clear definitions.

This is also why I keep asking you what formulas your arguments rest upon because to me it is not clear at all. So what formula is it that you use? Do you have something concrete in mind or is it more an intuition?

To illustrate the problems we get into, you wrote previously: RR is only used to compute the prior, all evidence is still weighed using all of b minus RR.. Lets try to make this concrete. You are saying there is other information R (presumably, part of the Gospels in the case of Jesus) which contains the RR relevant prior information. That is, the prior as established by the RR reference classes is really:

p(~H|R)

where

R : “Rank-Raglan information (born of a virgin, etc.)”

In addition to this we have to account for the difference between ~h and ~H. Lets suppose

~h = ~H . M

where M are the additional 5 elements of myth we have discussed up to this point (died and rose from the dead in the supernatural realm and so on).

So what exactly is it that you have in mind? My own thoughts is that we start from the joint distribution:

p(E,~H,M,R,B,C)

Since we want to use our RR prior we should have a factor p(~H|R). So:

p(E,M,B,C|~H,R)p(~H|R)p(R)

(we can ignore p(R) since it is just a constant). But what then? If C guarantees M (the additional elements in ~h compared to ~M) then we should condition M on C. Then we obtain:

p(E,B|~H,M,R,C)p(M|~H,C,R)p(C|~H,R)p(~H|R)p(R)

Using p(M|~H,C,R) = 1 by assumption (this is what places limits on what C can be) then

p(E,B|~H,M,R,C)p(C|~H,R)p(~H|R)p(R)

Okay so we got some of the way, but notice that this expression has two interesting features which differs from what is in OHJ:

1) Background information now figures as the evidence 2) we have a new conditional expression, P(C|~H,R).

To focus on the last expression neither you, Carrier or I have specified what C is. However if we assume C is a specific piece of information which makes “died in the supernatural realm” very plausible, presumably such a piece of information is at least somewhat surprising given only ~H and RR. After all, as far as I know, most of the RR-type hero figures are not thought to have died in the supernatural realm and had a resurrection, so even a basic frequency computation such as Carriers would push down this number. How likely? How unlikely? Well, to begin to answer those questions we got to specify what C is.

Ofcourse, the above does not capture your description RR is only used to compute the prior, all evidence is still weighed using all of b minus RR., so if you got some other computation in mind please just write it.

I don’t want to win an argument by demanding you give formulas, but I have tried to base my evaluation of OHJ on how well it conforms to the basic rules of probability — which is what Carrier himself suggest. I can appreciate we can have reasoned disagreement, however I hope you accept why I am reluctant to just accept reasoning which is not specific (from a formal point of view) and which is contrary to what I think I have derived.

Re. the p(~h|Gospels.b) = 93.75%. I think we are in agreement the result seems absurd if taken literally (i.e. with ~h rather than ~H) since the Gospels are not evidence that Jesus was buried in the supernatural realm. If you replace ~h with ~H, the result becomes more reasonable but I still don’t think the Gospels provide strong enough evidence to warrant such a conclusion. That’s just my own thoughts.

“p(~h|Gospels.b) = 93.75%. I think we are in agreement the result seems absurd if taken literally (i.e. with ~h rather than ~H) since the Gospels are not evidence that Jesus was buried in the supernatural realm.”

Here’s the mistake. They don’t have to support every single statement of the hypothesis. They only must not contradict any of them.

If we assume that either h or ~h is true, and conclude that gospels contradict h then they are indeed evidence for ~h.

“as far as I know, most of the RR-type hero figures are not thought to have died in the supernatural realm and had a resurrection, so even a basic frequency computation such as Carriers would push down this number.”

Another of the same kind.

An RR hero must only meet the RR criteria, anything else is irrelevant, it doesn’t matter if they were ever thought to live in a supernatural realm or to like ice cream, that doesn’t make them RR heroes any less.

“if we assume C is a specific piece of information which makes “died in the supernatural realm” very plausible, presumably such a piece of information is at least somewhat surprising given only ~H and RR”

Not surprising at all. It supports ~H and is not in conflict with RR.

“That means that when we add information to b (such as C) we have to be able to account for where that information goes in subsequent computations.[…]I provide an example of how (seemingly) trivial information added to our background knowledge can dramatically affect our conclusions . “

We don’t add anything to background knowledge. It’s just all we have at our disposal, and it goes simply wherever it’s relevant.

We can only fail to realize the relevance of some piece, or be ignorant of, or withhold if we’re dishonest.

That a piece of knowledge can change our conclusions is a truism.

Your calculations look all kinds of wrong.

M is not difference between ~H and ~h, its what they have in common. it doesn’t belong in background knowledge (it so happens that P5 does but it’s redundant as a part of ~h), and you freely swap e for b and h and back.

Look, if you used RR to calculate the prior, you can’t use it to judge the evidence, that means you can’t say gospels argue against h cause the character is portrayed as an RR hero, even if you think it’s the case, because it’s already accounted for, simple as that.

Carrier’s formula might look like P(h|RR) * P(e|h.(b-RR)) /…

Here’s the mistake. They don’t have to support every single statement of the hypothesis. They only must not contradict any of them.

If we assume that either h or ~h is true, and conclude that gospels contradict h then they are indeed evidence for ~h.

So in your view, my mistake is that the statement p(~h|Gospels.b)=93.75% does not imply directly that each of the components in ~h (such as Jesus being buried in the supernatural real) is at least 93.75% probable? I thought we had already agreed on this and that the conclusion seemed implausible. Otherwise just look above where I show this is indeed implied.

Insofar as your comment, we already agree that ~h and ~H (bare mythicism) are not the same. So we can’t assume that either h or ~h are true (despite what the notation might lead us to think). So even if we say the Gospels “contradict” h, by which I assume you mean p(h|Gospels.b) is low, we cant conclude that p(~h|Gospels.b) is high.

Tim: “as far as I know, most of the RR-type hero figures are not thought to have died in the supernatural realm and had a resurrection, so even a basic frequency computation such as Carriers would push down this number.”

Another of the same kind.

An RR hero must only meet the RR criteria, anything else is irrelevant, it doesn’t matter if they were ever thought to live in a supernatural realm or to like ice cream, that doesn’t make them RR heroes any less.

Well, ~h (which is what Carrier computes the prior of) include “buried in the supernatural realm”. So if i simply compute the prior probability of ~h using the RR reference class it is:

p(~h|RR) = (Characters in RR which matches ~h, which by definition includes being burried in the supernatural realm)/(Characters in RR)

(which is what a reference class suggest we do — if you don’t believe so please just provide a reference or your own definition) we get that p(~h|RR) is very low. You can say: No, I prefer to substitute ~h with something else. But this is just saying that you decide to not follow the definition or that you prefer to compute the prior probability of something else. Or you can say: No, I prefer to substitute h rather than ~h in the above definition and then use the result to conclude p(~h|RR) is high. However why make this choice and not the other? At best, it shows that the process of using reference classes is arbitrary. Do you see the problem?

If you want a reference on the above, just start with wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reference_class_problem and notice that in the article G is ~h. Please notice that *I* don’t think this is a valid way to determine a prior.

Your calculations look all kinds of wrong.

M is not difference between ~H and ~h, its what they have in common.

it doesn’t belong in background knowledge (it so happens that P5 does but it’s redundant as a part of ~h), and you freely swap e for b and h and back.

I think you go wrong here. Since ~h (Carriers myth theory) contains ~H (bare myth) what ~h and ~H have in common is exactly ~H (think about it). I defined M as being what is added to ~H to produce ~h: I.e. that Jesus was burried in the supernatural realm etc. This is just some basic notation so we have something concrete to talk about.

What do you mean I freely swap e for b and h? Please just provide whatever computation you have in mind and if it agrees with the rules of probability theory I am convinced.

Look, if you used RR to calculate the prior, you can’t use it to judge the evidence, that means you can’t say gospels argue against h cause the character is portrayed as an RR hero, even if you think it’s the case, because it’s already accounted for, simple as that.

Carrier’s formula might look like P(h|RR) * P(e|h.(b-RR)) /…

You are arguing based on what your intuition tells you we should do and not what probability theory actually tells us we have to do. Probability theory has to be the arbiter of truth and what you are saying just does not follow as far as I can see. Please just start with p(~h|b.E) and try to derive your expression, I promise you that it can’t be done symbolically.

I am not trying to browbeat you with math, however we must recognize we are arguing about what is essentially dressed up high-school math. If i wrote down a derivation of (for instance) the derivative of a function, and you told me that it “looked wrong”, I think it would be a fair request that you provided your derivation or at least showed exactly where I went wrong, exactly. I know it is impressive when Carrier (who has written a book on the subject) says that something can or can’t be done. He is very skilled rhetorically and convincing, but on this particular topic he is quite often wrong and if you notice very rarely provide math to substantiate what he says.

If you wish to continue the discussion we could perhaps do it on earlywritings.com:

http://earlywritings.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=2224

“I think you go wrong here. Since ~h (Carriers myth theory) contains ~H (bare myth) what ~h and ~H have in common is exactly ~H (think about it). I defined M as being what is added to ~H to produce ~h”

This.

~h is a subset of ~H, period. A guy said to be living in a supernatural realm (~h) is by definition, mythical (~H), however there are other variants of myth which don’t involve this (still ~H but not ~h).

Sorry. You can’t derive anything that makes sense, mathematically or otherwise, if you’re making basic mistakes like this.

Hi again Zbykow,

This.

~h is a subset of ~H, period. A guy said to be living in a supernatural realm (~h) is by definition, mythical (~H), however there are other variants of myth which don’t involve this (still ~H but not ~h).

Ah, I see why the confusion arises. So far we have talked about ~h and ~H as logical propositions. For instance in my definition above:

~h = ~H . M

the use of periods (and) and negation (~) indicates that we are discussing logical propositions. You are correct that if ~H and ~h are considered as sets then the set (~h) is a subset of (~H) and in that case it is true that the set ~h is contained in ~H. However, considered as propositions the definition of ~h is a series of conjunctions which encompass ~H:

~h = ~H . (myth element 1) . (myth element 2) … (myth element 5).

It is in this sense I meant ~H is what ~h and ~H have in common. None of this affects my derivation of the above formulas; they are just assuming a notation where we use logical propositions as we have used up to this point. Again I must re-ask the question: Where do I go wrong in your view? What is the right computation? .

By the way, if we assume set notation, then when you write:

M is not difference between ~H and ~h, its what they have in common.

Then what ~h and ~H have in common is the intersection of these two sets (~h) and (~H). In this case that would still not be M (considered as a set) but (~h). If you wish to accuse someone of being flat out wrong on the math it is advisable to check the computations twice :-).

By the way, regarding your comment: “Carrier’s formula might look like P(h|RR) * P(e|h.(b-RR))”, can you provide the derivation that leads to that? I am still not seeing it at all.

By the way, I invite you to discuss this topic further at earlywritings.com.

“It is in this sense I meant ~H is what ~h and ~H have in common.”

~H is not what ~h and ~H have in common, in any sense, ~h is.

I got a hunch that you still think P5 is somehow incompatible with ~H, but this is already going too long.