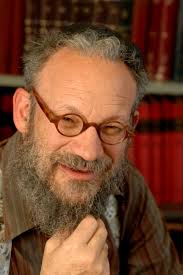

Daniel Boyarin is a Jewish scholar of some repute. His work is worth consideration alongside what often amounts to little more than Christian apologetics thinly disguised as disinterested scholarship. In The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ Boyarin argues that the Christian belief in a suffering messiah who atones for our sins was far from some bizarre offence to Jews but in fact was itself an established pre-Christian Jewish interpretation of the books of Isaiah and Daniel.

“But what about Paul writing to the Corinthians about the cross of Christ being an offence to the Jews?” you ask. And in response I will step aside and allow a professor of ancient history at Columbia University, Morton Smith, to explain that most Christians have badly misunderstood that passage: see Was Paul Really Persecuted for Preaching a Crucified Christ?

So this post will look at Daniel Boyarin’s argument for the very Jewish (pre-Christian) understanding of the suffering messiah.

The idea of the Suffering Messiah has been “part and parcel of Jewish tradition from antiquity to modernity,” writes Boyarin, and therefore the common understanding that such a belief marked a distinct break between Christianity and Judaism is quite mistaken.

The evidence for this assertion? This post looks at the evidence of Isaiah 53. (Earlier posts have glanced at Boyarin’s discussion of Daniel in this connection.) Christians have on the whole looked at Isaiah 53 as a prophecy of the suffering Messiah. Fundamentalists have viewed the chapter as proof-text that Jesus is the Christ (Messiah). Jews, it has been said, reject the Christian interpretation and believe the passage is speaking metaphorically about the people of Israel collectively. Before continuing, here is the passage itself from the American Standard Version:

53 Who hath believed our message? and to whom hath the arm of Jehovah been revealed?

2 For he grew up before him as a tender plant, and as a root out of a dry ground: he hath no form nor comeliness; and when we see him, there is no beauty that we should desire him.

3 He was despised, and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and as one from whom men hide their face he was despised; and we esteemed him not.

4 Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows; yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted.

5 But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities; the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed.

6 All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way; and Jehovah hath laid on him the iniquity of us all.

7 He was oppressed, yet when he was afflicted he opened not his mouth; as a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and as a sheep that before its shearers is dumb, so he opened not his mouth.

8 By oppression and judgment he was taken away; and as for his generation, who among them considered that he was cut off out of the land of the living for the transgression of my people to whom the stroke was due?

9 And they made his grave with the wicked, and with a rich man in his death; although he had done no violence, neither was any deceit in his mouth.

10 Yet it pleased Jehovah to bruise him; he hath put him to grief: when thou shalt make his soul an offering for sin, he shall see his seed, he shall prolong his days, and the pleasure of Jehovah shall prosper in his hand.

11 He shall see of the travail of his soul, and shall be satisfied: by the knowledge of himself shall my righteous servant justify many; and he shall bear their iniquities.

12 Therefore will I divide him a portion with the great, and he shall divide the spoil with the strong; because he poured out his soul unto death, and was numbered with the transgressors: yet he bare the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors.

Here is Daniel Boyarim’s startling claim:

[W]e now know that many Jewish authorities, maybe even most, until nearly the modern period have read Isaiah 53 as being about the Messiah; until the last few centuries, the allegorical reading was a minority one.

Aside from one very important — but absolutely unique — notice in Origen’s Contra Celsum, there is no evidence at all that any late ancient Jews read Isaiah 52-53 as referring to anyone but the Messiah. There are, on the other hand, several attestations of ancient rabbinic readings of the song as concerning the Messiah and his tribulations. (p. 152)

In the Palestinian Talmud there is an amoraic [i.e. from between 200 and 500 CE] passage (Sukkah 5:2 55b) discussing the meaning of a verse in Zechariah:

And the land shall mourn (Zechariah 12:12)

One opinion expressed is that this refers to the Messiah — that is, that the land will mourn over the Messiah. (The other view is that it refers to the death of sexual desire in the messianic age.)

Other traditions appear in the Babylonian Talmud from a later period (300 to 600 CE) “but very likely earlier” (p. 153). One of these is from Sanhedrin 98. The question is there asked “What is the Messiah’s name?” Different rabbis offer various answers.

After several views, we find: “And the Rabbis say, ‘the leper’ of the House of Rabbi is his name, for it says, ‘Behold he has borne our disease [the word here means ‘leprosy’], and suffered our pains, and we thought him smitten, beaten by God and tortured’ [Isa. 53:4].”

So here we find Jews interpreting Isaiah 53 as a prophecy of the vicarious sufferings of the Messiah.

Boyarin then mentions that on the previous page in the Talmud is a scene of the Messiah sitting among the diseased and poor at the gates of Rome, and understanding that he has a saving role to perform for these wretched sufferers by identifying with them.

One more passage is brought forth as a witness although Boyarin advances it with some caution. It is known only from “a polemic Testimonia (of a thirteenth-century Dominican friar)”. If genuine, it would be evidence that from the third century that rabbis interpreted the Suffering Servant of Isaiah 53 as the Messiah who must suffer to atone for sins. This is the passage:

Rabbi Yose Hagelili said: Go forth and learn the praise of the King Messiah and the reward of the righteous from the First Adam. For he was only commanded one thou-shalt-not commandment and he violated it. Behold how many deaths he and his descendants and the descendants of his descendants were fined until the end of all the generations. Now which of God’s qualities is greater than the other, the quality of mercy or the quality of retribution? Proclaim that the quality of goodness is the greater and the quality of retribution the lesser! And the King Messiah fasts and suffers for the sinners, as it says, “and he is made sick for our sins, etc.” ever more so and more will he be triumphant for all of the generations, as it says, “And the Lord visited upon him the sin of all.”

(I avoid further discussion of some of the debates about the authenticity of this passage here. Perhaps they can be discussed in comments if anyone is interested.)

Medieval Jewish interpreters

Boyarin cites a few medieval Jewish commentators who, though marginal to rabbinic Judaism, can nonetheless “hardly be suspected of Christian leanings”.

Yefet ben Ali, a Karaite: believed Isaiah 53 was a messianic passage and that the Suffering Servant was indeed the Messiah.

Rabbi Moshe Alshekh, a Kabbalist, but “a spotlessly ‘orthodox’ rabbinic teacher”, wrote,

I may remark, then, that our Rabbis with one voice accept and affirm the opinion that the prophet is speaking of the King Messiah, and we ourselves also adhere to the same view.

Rabbi Moses ben Nahman, a leading Spanish Jewish intellectual, acknowledges that according to the midrash and the Talmud Isaiah 53 speaks of the Messiah — although he himself disagreed.

Conclusion

The evidence testifies that the Jews have never spoken with one voice on the meaning of Isaiah 53 and the identity of the Suffering Servant. It cannot be said that the Christian interpretation was original nor that it constituted a break with “Judaism” or the religion of Israel.

Indeed, in the Gospels these ideas have been derived from the Torah (Scripture in its broadest meaning) by that most Jewish of exegetical styles, the way of midrash.

Even if the Christians originated this particular midrash [and by midrash Boyarin means “a way of multiply contextualizing verses with other verses and passages in the Bible, in order to determine their meaning” p. 148] the way they did so (“the hermeneutical practice they were engaged in”), their religious thinking, imagination and interpretation was entirely Jewish.

There is no essentially Christian (drawn from the cross) versus Jewish (triumphalist) notion of the Messiah, but only one complex and contested messianic idea, shared by Mark and Jesus with the full community of the Jews. The description of the Christ predicting his own suffering and then that very suffering in the Passion narrative, the Passion of the Christ, does not in any way then contradict the assertion of Martin Hengel that “Christianity grew entirely out of Jewish soil.”

Gospel Judaism was straightforwardly and completely a Jewish-messianic movement, and the Gospels the story of the Jewish Christ. (pp. 155-156)

I’m also interested in the equating of “bearing our diseases” in Isaiah 53 with “leprosy”. Is there any significance with the not insignificant role of lepers in the Gospel of Mark: 1:40-45 and 14:3.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Leprosy? I would think about a possible link with Simon Magus (or Simon the leper)…

I don’t know. This flies in the face of most of what I’ve read on the subject. The Suffering Servant, as I’ve understood it, is not a Messianic figure. The next thing this author may claim is that the Messiah was expected to be crucified and raised from the dead. Then the author can become a Christian convert, or maybe we’ll end up with one religion instead of two.

I am tempted to still view Christianity as hellenized Judaism. It seems a universalized form of an ethnocentric religion. It allows “spiritual Jews” to see themselves in scriptures their ancestors were never represented in.

It seems the fulfillment of the envy of Pagans for the normative laws of the Hebrew Bible.

It seems to me Philo of Alexandria proposes what became important ideas for Christianity including the Logos, and, that he is a hellenized Jew (using midrashic method).

I’m reading Philo now to see whether I can line up central principles of neoplatonism with the formulation of the biblical Jesus. It seems Philo applied his dualistic ideas and the concepts of macrocosm and microcosm pretty broadly. I will take care not to ascribe ideas to Philo that were not his. Thanks for being a great source of info, Neil Godfrey.

Philo proposed the Word made flesh.

“And even if there be ***not as yet any one*** who is worthy to be called a son of God, nevertheless let him labour earnestly to be adorned according to his first-born word, the eldest of his angels, as the great archangel of many names; for he is called, the authority, and the name of God, and the Word, and man according to God’s image, and he who sees Israel. If we are not yet fit to be called the sons of God still we may deserve to be called the children of His Eternal Image, of His most sacred Word;”

– Philo, “On the Confusion of Tongues,” (146)

And then the gospel story was written.

Nice! A generation ago, Philo and Josephus were the second and third authors added after the Bible itself, to a scholar’s reading list on Christianity. Sadly, that has been recently forgotten.

Hebrews 8.5 is Plato’s Theory of Forms.

Dr. Boyarin’s take on Isaiah 53 is thought-provoking and makes considerable sense.

But we cannot avoid the admission that when we attempt to reconstruct conceptual categories two thousand or more years old, upon whatever evidence (textual, archaeological, or otherwise) that happened to survive or be discovered to date, we are inherently engaged in speculation. Some of it may be more informed than others, some of it may be more congruent with other speculation, but essentially that is all that any of us are doing–from the most august and credentialed expert to the avid, educated amateur.

During Jesus’ day, what were the current Jewish concepts providing content to the titles of prophet, messiah, suffering servant, son of man, son of god, etc.? Doesn’t it seem likely that there were a kaleidoscope of such concepts–shifting in nature, form, and detail–that were largely dependent upon the historical and geographical context of the particular Judaism in question, whether it was more or less Temple-centered, more or less Temple-adverse, more or less traditional, more or less Hellenized, more or less militant toward Rome, more or less placating toward Rome, more or less affiliated with established sects like Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, etc.?

Not to put Dr. Boyarin in this camp by any means, but I am doubtful of anyone who contends that he or she, after several years of study or a lifetime of academic work, can clearly sort out this kaleidoscope and state definitively (or even confidently) that one single view of any one of these titles was predominant in any Jewish venue in or around the periods immediately preceding or following the destruction of the Temple.

That said, the “consensus” interpretation of Isaiah 53 has always bothered me, because the connotation of the piece, the vibe it always gave me as a reader, did not seem to jibe with a purely corporate figure, a metaphor for an entire people. How could an entire people, who suffer because of their sins, take all of those sins upon themselves and somehow become their own redeemer? Bit of a stretch.

@ Giuseppe — agreed. Interesting. One does wonder.

@ Ken — Dan Boyarin does indeed argue Christianity and Judaism (as we know them today) were not really separate religions (as we understand religions) for up to the first four centuries of the “Christian era”. (See So Long Indistinguishable for example.) Yes we read denunciations of each other, but we find the same denunciations directed at fellow Jewish and Christian sects also.

@ Phil — Yeh, Philo is a real eye-opener. Suddenly the gospels do not seem so unique after all.

@ newtonfinn — agreed about the difficulties trying to maintain the metaphorical interpretation. I’ve struggled with that, too. But then we have to ask what “Isaiah” himself had in mind when he wrote. Prefer to keep the comments here more pointed, though — they’re more likely to be read in blog-land that way, too.

P.S. (Epistemology, questions of speculation — we are aware of those well enough, but happy to discuss specifically in another context.)

“the gospels the story of the Jewish Christ.” Seems truer for the synoptics, esp. Matthew and Mark. Revelation is a Jewish text, which I mention because of dating issues. Recently read Pagels’ book on that text, hoping for some insight into its dating and composition, but didn’t get much. The dating of the gospels is important in estimating their degree of Jewishness, as well as their content. From the content, Luke is less Jewish and John not at all, and antisemitic. Gospels definitely derivative of Isaiah and Daniel, though, no question. This is why I tend to accept the earlier dating of Mark and Matthew, with Mark at about 70 CE and Matthew somewhere in the 80s. I know there are many who use much later dates.

I tend to date Mark early now for some of the same reasons you do. So many of its scriptural allusions to temple and its fall find most meaning at an earlier date. (Hope I’m not seeing these allusions through circularity, though.) But re John, Philo does not persuade you of John’s Jewishness?

Don’t take me for an NT scholar, Neil! I’m just a guy who reads the gospels. I see a note here in the ASV that says most of John’s prologue is written in a form resembling Semitic poetry, but what a Greek idea! Your description of Boyarin’s thesis makes sense, and I have no knowledge of the subject, but I’m merely saying that “from the content,” you have three stories about a sectarian conflict with Pharisees, and then you have John, which is about how the Jews think Jesus is a crazy Samaritan, and how they deliver him up to Pilate in exchange for Barabbas, because they hate him; i.e., they’ve gone from sectarian rivals to enemies. What’s Philo’s take?

My reading of Jewish Second Temple scholarship (not so much New Testament scholarship, perhaps) indicates that we cannot tease apart Jewishness from Hellenism so easily. Boyarin in one publication, iirc, even cites works that say Judaism was another form of Hellenistic culture. But this is pre-rabbinic Judaism of the Second Temple era. Philo contains many of the concepts we find in John — most notably the idea of a Logos figure appearing in human form (Moses) to dwell among his people.

While the prologue says Jesus came to his own and his own received him not, it does add that a few received him. We find in subsequent chapters that those who received him were expelled from the synagogue. They appear to have rejected their former earthly identities as Jews and, as Jewish factions were quite capable of doing at this time, labeled their factional opponents the “first born of Satan”.

Anti-semitic sentiments (the direction of the discussion below) appear to have found fuel in what were initially intra-Jewish denunciations. (Such are my thoughts of late. Remains to be seen where they are located a couple of years from now.)

Clarke: “From the content, Luke is less Jewish and John not at all, and antisemitic.”

Some recent scholars have concluded that John is not really antisemitic, and that the Dead Sea Scrolls give us some insights as to what he was actually saying. Consider, for example, the “sons of light” and “sons of darkness.” I can’t say I’m convinced either way, but it sure does seem that when John over and over says “the Jews,” he isn’t talking about Judaeans or “certain Jews,” but all Jews, and in a derisive, accusatory, antisemitic way.

Yes, and it should not surprise us that scholars recently conclude that John is not really antisemitic. Antisemitism is not in vogue, last time I checked, nor should it be.

It all depends on what is “meant” by “antisemitism”.

See e.g. Professor Denis MacEoin, “The New Racists” at

http://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/6415/christians-israel

Even if we find it hard to accept the point that the Suffering Servant was interpreted Messianically by some Jews in the pre-Christian era (though do also look at the post on Boyarin’s discussion of Daniel in this context, too) we cannot deny that among rabbinical Jews there were those who freely embraced the interpretation. That undeniable fact must force us to concede that the interpretation, or more particularly the manner in which the interpretation was derived, was not in itself offensive to Judaism or Jews. The traditional assumptions of (apolegetic) Christianity are open to doubt before we draw any other conclusions from the rabbinic evidence.

Excuse my ignorance, since I’m only an amateur, but it appears that all the sources Boyarin quotes are post Christian. Isn’t the question about whether or not pre-Christian Jews anticipated a suffering, dying and rising Messiah?

Yes, they are. And I often squirm when I see works trying to reconstruct early first century Galilee from third and fourth and fifth century rabbinic sources. But sometimes arguments can be made to justify the method and result.

It comes down to probabilities. The assumption is that it is extremely unlikely that rabbinic Jews would take on board a Christian interpretation — especially in the later centuries when there was strong hostility between Jews and Christians. The Talmudic texts claim to be documenting debates that have been handed down through tradition from the earlier times and that explanation makes more sense in this case.

Further, notice that some of the rabbinic references to a suffering messiah bear no resemblance to anything we know from Christian sources. Note in particular the scenario of the messiah at the gates of Rome. (In articles like this I like to take time to dig out and quote the Talmudic sources for myself but this time I opted to get the post up sooner rather than much much later that would have been required if I did the same this time.)

And then we have to ask for the origin of the Christian interpretations of Daniel and Isaiah. Where we see them using the same hermeneutical methods (“midrash”) as the Jews of the Second Temple era then we can have some confidence that the interpretation was influenced by that Jewish intellectual matrix.

Moreover, there are the text of Daniel and Isaiah themselves and other Second Temple interpretations. We see similar interpretations in this literature in relation to Isaac, for example — he was understood by some Jews to have actually been slain by Abraham then brought back to life, with his blood meanwhile atoning for the sins of all Jewish descendants. (See my posts on The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son.) And Daniel itself speaks of a dying messiah in its last chapters; and the Son of Man is said to be symbolic of the persecuted and suffering people who are raised back up again to a victorious state. We can trace the evolution of the interpretation of Daniel’s Son of Man from metaphor to a literal figure in Jewish texts.

Moreover, as Thomas L. Thompson and others have demonstrated, the concept of “messiah” in Jewish thought (Second Temple era) is far more fluid than traditionally assumed by many Christian scholars. The term applied to the High Priest whose death liberated those who had fled during his tenure to cities of refuge; Saul himself was called a messiah even at the time of his death on the battlefield, and so forth. See also

These are just a couple of examples. There are others. But putting it all together we have, I think, a very strong case for Paul’s concept of the messiah as discussed in Novenson’s Christ Among the Messiahs. (Paul’s writings are themselves evidence that the idea of a dying Messiah was a Second Temple Jewish idea.)

So I think we have reasonable grounds for accepting as a strong probability that the earliest Christians took their concept from the ideas in circulation in their day or at least put them together in a way that was entirely consistent with those wider Jewish ideas at the time.

Thanks for the question. Good one. Appreciated the opportunity to add these thoughts.

“here is the passage itself from the American Standard Version:”

JW:

Who Isaiah 53 refers to is not an interesting subject any more in polemics because Christian Bible Scholarship generally concedes that it refers to Israel but Jesus Neil, you are using a CHRISTIAN translation to present it? I mean isn’t that how Christianity got started (proof-texting from Christian translations of The Jewish Bible). As Yeshu Barra said, “Sounds like Deja Jew all over again.”

Joseph

So what is there in the ASV that misleads with any sort of “proof-texting” in its deviously mischievous translation in here?

Would you prefer I use a translation from Judaism Is The Answer site as you yourself do — kosher pristine and guaranteed to be “free” from all apologetic interests?

But you are quite right. I should have added the same translation Boyarin himself used. Maybe it was his own translation — in which case we might ask if that translation is biasing us towards his argument. If you care to type it all out for me and send it to me as a text file and get approval from either him or his publisher (whoever owns the copyright) I promise to include that here instead of or alongside my lazy copy and paste job from the first translation I saw on Mark Goodacre’s BibleStudyTools website.

Meanwhile, I do thank you for demonstrating the implausibility of Jewish interpreters ever adopting the Suffering Messiah motif via Christian influence.

Always thought the Book of Daniel and the Gospel narratives are closely linked, including the 70 Sevens “time frame”. Have any non-christian analysts investigated this in detail?

Suffering messiah maybe. The problem was the very non-Jewish idea of a suffering God. Which was far, far more Greco Roman, Dionysiac, than Jewish.

Yes. And when Boyarin starts quoting Rabbi Moshe Alshekh, to support his thesis, he’s not only post-Jesus, he’s post Aquinas.

Boyarin’s “thesis” is that the idea of a Suffering Messiah has been part of Judaistic tradition throughout most of the history of Judaism and it is only in the few centuries that the popular assumption that the idea is alien to Jewish thinking has so totally prevailed. Recall his point:

That’s the reason he has quoted rabbis and Jews well into the Middle Ages and beyond. It is to show that historically the concept has not been completely alien to Judaism as we today have come to believe.

I think Boyarin is right about Isaiah 53, but even if he isn’t Isaiah 53 could still have been used by the original Christian writers in haggadic midrash to generate the passion story in Mark. Even if no other Jews were viewing Isaiah 53 as referring to the messiah, Christians could still have been the first to do so. Recall in “New Testament Narrative as Old Testament Midrash” where Robert M. Price explains that:

“Thus modern scholars might admit that Hosea 11:1 (“Out of Egypt I have called my son”) had to be taken out of context to provide a pedigree for the fact of Jesus’ childhood sojourn in Egypt, but that it was the story of the flight into Egypt that made early Christians go searching for the Hosea text. Now it is apparent, just to take this example, that the flight into Egypt is midrashic all the way down. That is, the words in Hosea 11:1 “my son,” catching the early Christian eye, generated the whole story, since they assumed such a prophecy about the divine Son must have had its fulfillment. And the more apparent it becomes that most gospel narratives can be adequately accounted for by reference to scriptural prototypes, Doherty suggests, the more natural it is to picture early Christians beginning with a more or less vague savior myth and seeking to lend it color and detail by anchoring it in a particular historical period and clothing it in scriptural garb.”

So just like the original Christian writers took Hosea 11:1 (“Out of Egypt I have called my son”) as referring to Jesus (when “son” originally referred to the Jewish people in the Old Testament), so to did the original Christians rewrite Isaiah 53 to create the passion narrative, (along with Psalms, and the Wisdom of Solomon.)

The New Testament writers were pretending Jesus was fulfilling all kinds of Old Testament scripture in order to sell Him and win converts:

(A) 17 And Jesus said to them, “Follow Me, and I will make you become fishers of men.” (Mark 1:17)

(B) The Great Commission

16 Then the eleven disciples went to Galilee, to the mountain where Jesus had told them to go. 17 When they saw him, they worshiped him; but some doubted. 18 Then Jesus came to them and said, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. 19 Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, 20 and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age.” (Matthew 28:16-20)

(C) Sending out Emissaries

Just as Moses had chosen twelve spies to reconnoiter the land which stretched “before your face,” sending them through the cities of the land of Canaan, so does Jesus send a second group, after the twelve, a group of seventy, whose number symbolizes the nations of the earth who are to be conquered, so to speak, with the gospel in the Acts of the Apostles. He sends them out “before his face” to every city he plans to visit (in Canaan, too, obviously).

To match the image of the spies returning with samples of the fruit of the land (Deuteronomy 1:25), Luke has placed here the Q saying (Luke 10:2//Matthew 9:37-38), “The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few; therefore beg the Lord of the harvest to send out more workers into his harvest.”

And Jesus’ emissaries return with a glowing report, just as Moses’ did.

(Deuteronomy 1; Luke 10:1-3, 17-30)

The argumentation of Boyarin, and Godfrey after him, is an absolute disaster.

First of all, the arguments are all based in rabbinical sources. So, it’s impossible to asume that pre-Christian Judaism believed in a Suffering Messiah. It is a falacy of fake confirmation: I can demonstrate that Judaism beleived in a suffering Messiah in rabbinical ages (II Century and thereafter), so I am demonstrating that Judaism beleived in a suffering Messiah previous to Ist Century.

Excuse me. That’s a completely defecting reasoning.

Let’s see: Judaism asume that the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 is the people of Israel, not because a deduction, but because “the Servant” that continually appears in Isaiah 40 to 55 is explicitly identified as Israel (for example, Isaiah 49:3).

Boyarin argues that there is only one ancient source –Origin– that makes that identification, but forget to say that ther is no single textual source that speaks of Isaiah 53 as a messianic prediction of a suffering Messiah. Still with Origin as our very lonely source to support the idea of Israel as the suffering servant, those who take this interpretation as accurate are winning to the other side 1-0.

To relate Isaiah 53 with the Messiah is very common in Rabinnic Judaism, because it is a tipical belief influence by the exile. Exilic theology in a 100%.

The most ancient source that made this identification is the Targum Jonathan, that begins Isaiah 52:13 with the words “Behol my servant the Messiah…”, but it is absolutely clear that Isaiah 53 in the Targum is a voluntary distorsion of the original text, focused on the tragedy of Simeon bar Kochba.

That historical evente, the most traumatic for ancient Judaism, is the turning point in this issue: previous to the Bar Kochba’s revolt, no single jewish author spoke about a suffering Messiah, except Daniel 9:26 (that, in fact, did not speak about a suffering Messiah, but about a murdered Messiah). After Bar Kochba’s defeat, all jewish authors began to speak about him.

It’s so clear: if you make a full revision of the classical messianic expectations of Judaism since III Century, all af them are a nostalgy of Bar Kochba.

I insist: messianic traditions for Rabbinical Judaism are exilic theology.

How others interpreted Isaiah 53 is irrelevant, because the Christians often offered idiosyncratic understandings of the Septuagint, such as with Hosea 11:1 (“Out of Egypt I have called my son”).

You are absolutely correct when you write:

I have made the very same point myself when I see arguments like that.

But you are mistaken when you impute that argument to Boyarin. (And even more mistaken when you impute it to me as well!) Boyarin “assumes” nothing about the first century on the basis of rabbinic sources. In my series of posts on Boyarin I have pointed out his argument that Jews were not likely to have borrowed interpretations about the Messiah from Christians in the rabbinic era. Boyarin’s argument is that Christianity itself began from the matrix of Jewish religious ideas and ways of interpreting the Scriptures. These are arguments for continuity. There is no mindless “assumption” involved at all.

As for my own arguments, I have been posting along similar lines to what you argue re Bar Kochba and his influence on rabbinic ideas.

But there are also studies demonstrating that Daniel’s messianic concepts are linked to Isaiah 53, and we see a trajectory through Enoch to the later Jewish and Christian ideas.

Boyarin also holds that this Messiah was the pre-extant Jewish figure of Jesus Christ, “a simile, a God who looks like a human being” (p.31), namely Daniel’s Son of Man i.e. Angel of the Lord i.e. Philo’s divine Logos i.e. the late Second Temple era figure of a chief heavenly mediator. (see Garrett et al.) And he asserts “the theological controversy that we think exists between Jews and Christians was already an intra-Jewish controversy long before Jesus” (p.35), as per his assertion that the author of the Book of Daniel “wanted to suppress the ancient testimony of a morethan-singular [sic] God” (p.35).

I do apologize for your comment getting caught up in moderation for so long. That should not have happened. Anyway, it is published now.

The description of the Jewish people as “My servant” ends a chapter and the new chapter describing “My righteous servant” leading into Isaiah 53 begins.

The man described is G-d’s anointed king upon whom the spirit of G-d and the person of the spirit of the Holy G-d alights upon in Isaiah 11 and he is the teacher of righteousness who is Elijah.

Elijah arrives with the angel of the covenant of sin forgiveness and reconciles the sons to the fathers and the fathers to the sons through the teachings of the L-rd given to Moses at Horeb.

The description of the Jewish people as “My servant” ends a chapter and the new chapter describing “My righteous servant” leading into Isaiah 53 begins.

Jews For Judaism: Isaiah 53 Verse by Verse; with Commentary by G-d’s Righteous Servant of Isaiah 53 the Teacher of Righteousness Keith Ellis McCarty, Priest of the G-d of Israel https://keithmccartymccarty.wordpress.com/2017/07/08/jews-for-judaism-isaiah-53-verse-by-verse-with-commentary-by-g-ds-righteous-servant-of-isaiah-53-the-teacher-of-righteousness-keith-ellis-mccarty-priest-of-the-g-d-of-israel/