John Drury, DD, in The Parables of the Gospels, explains why it is very doubtful that Jesus ever spoke the parable of the Good Samaritan. The evidence points towards the real author of this parable being the same person who was responsible for the work of Luke-Acts. For convenience we’ll call him as Luke.

The parables of Jesus in the Gospels of Mark and Matthew are strongly allegorical. In the Gospel of Luke their allegorical character takes a back seat. The parables in this third gospel are found to be more “realistic stories which are rich in homely detail and characterization.” (Drury, p. 111)

It is not likely that different traditions, one recalling allegorical parables spoken by Jesus and the other more realistic stories of his, went their own distinct ways so that Matthew heard one sort and Luke the other. I think it’s more reasonable to suggest that we see the creative hands of the authors at work.

The All Important Mid-Turning Point

Another indicator that Luke’s creative imagination was responsible for the parables unique to his gospel is their structure.

L [i.e. unique to Luke] parables have a characteristic shape of which the most striking feature is that the crisis happens in the middle, not, as so often in Matthew’s parables, at the end. (Drury, p. 112)

It is this “middle” part of the story, or the mid-point in time, that is the turning point. Not that this observation is original with Drury. It is a familiar pattern to students of Luke’s parables ever since Conzelmann’s The Theology of Saint Luke.

This pattern is in fact a characteristic of all of Luke’s work, so much so that Drury can say

The pattern in the L parables is deeply embedded in Luke’s mind. It is the pattern of the whole of his history. Jesus in his Gospel is not history’s end but its turning point, setting it on a new course in which Judaism drops away and the Christian Church goes triumphantly forward. (p. 113)

So the story of Jesus begins in a narrative rich in allusions to the patriarchal stories of Genesis and Judges, proceeds to portray Jesus as the new Elijah (contrast Mark and Matthew who gave this role to John the Baptist), and follows up Jesus’ mission with the growth of the church as seen in his parables and in Acts. Jesus is the mid-point or turning point of the grand narrative.

This carries over to Luke’s eschatology. In Luke we read less of the end of the age, period, than we do of the end of a person’s life. But that end of the individual’s life is not the end of the story. Consequences of the life led follow. The individual’s end is the turning or mid-point. In the parable of the rich fool, for example, the crisis comes with his unexpected death and this is followed by the punishment he must receive in his afterlife. For Luke the “end” is moved from the cosmic to the individual level.

It’s the way Luke thinks and the way he designs narratives. He didn’t just happen to inherit a subset of parables from Jesus that coincidentally matched his own literary-narrative style and no-one else’s. The parables of Jesus in Luke’s gospel are Luke’s own creations.

If only by symmetry of pattern, the L parables fit perfectly into Luke’s perception of the historical significance of Jesus’ biography.

By contrast Matthew was “very ready to end his parables with the end of time.”

The All Important Individuals

Mark’s parables were generally about nature but he introduced people into his parable of the vineyard. God’s ambassadors met with persecutors.

Matthew added people to some of Mark’s nature parables (e.g. the seed growing secretly became the parable of the wheat and the tares and included dialogue between a farmer and his labourers) and introduced new parables all with human agents. The people in Matthew’s parables are all collective stock figures, classes of people who were either good or bad by nature. The most tolerance he would show towards the wicked was a willingness to let them be until their day of judgment fell.

Luke takes the personal element to its next level. The people in Luke’s parables are individuals, not collectives. They are not cast in black or white but are able to change, repent, mix good actions with wrong motives. This more realistic psychological awareness is true of Luke’s characters generally and not just those in parables. Zacchaeus has a change of heart; the prodigal son does a turnabout in relation to his father; the unjust judge does not want to put himself out but in the end does the right thing out of self-interest; among other cases.

Luke’s people have understandable motives, they are something more interesting than sons of light or sons of darkness, and they have the limited but critical freedom of decision which we all exercise. (p. 116)

The Less Important Allegory

Jesus’ parables in Luke are not without allegory but the distinctly Lukan parables can well be understood without reference to allegory. The people themselves act out the message in a way for anybody to understand. The parables are not supernaturally revealed wisdom. There is no need for a key to unlock mysteriously coded meanings.

People interact so intelligibly that a modest knowledge of human character is all we need to grasp them. They are wisdom parables in the older and more mundane sense of wisdom – that art of coping which the Book of Proverbs put in aphorisms. As stories they are like the Joseph saga or the court chronicles of David and Solomon. (p. 116)

Allegory is not totally absent, however. Samaritans, we come to realize, are symbolic of “the other”. The good Samaritan contrasted with the religious elites, the Samaritan leper among the nine other lepers, are precursors to the episode in Acts where the church expands beyond Jerusalem to evangelize Samaria. Suggestive symbolism enriches the prodigal son parable: the father represents God, the elder son represents mainstream Judaism, association with pigs brings gentiles to mind. At the same time, however, the key message of the parables can be understood without knowledge of their allegorical tapestry.

Notice. . . . .

The friend at night (Luke 11:5-8) Drury sees the rousing of the neighbour as the crisis. One might assign the neighbour turning away from his friend’s need as the crisis but the story but the narrative world consists of a guest turning up unexpectedly and the urgent need to feed him, followed by coming at midnight to a friend with a request, and eventually the friend’s relenting to the request.

Note also the rich dialogue and change of heart among the characters.

And he said unto them, Which of you shall have a friend, and shall go unto him at midnight, and say unto him, Friend, lend me three loaves;

For a friend of mine in his journey is come to me, and I have nothing to set before him?

And he from within shall answer and say, Trouble me not: the door is now shut, and my children are with me in bed; I cannot rise and give thee.

I say unto you, Though he will not rise and give him, because he is his friend, yet because of his importunity he will rise and give him as many as he needeth.

The tower builder (Luke 14:28-30) — he fails to appreciate the mid-term crisis being in such a hurry to finish:

For which of you, intending to build a tower, sitteth not down first, and counteth the cost, whether he have sufficient to finish it?

Lest haply, after he hath laid the foundation, and is not able to finish it, all that behold it begin to mock him,

Saying, This man began to build, and was not able to finish.

The kings at war (Luke 14:31-32) — also a lesson on the importance of planning for the “middle stage”:

Or what king, going to make war against another king, sitteth not down first, and consulteth whether he be able with ten thousand to meet him that cometh against him with twenty thousand?

Or else, while the other is yet a great way off, he sendeth an ambassage, and desireth conditions of peace.

The unjust steward (Luke 16:1-12) we see the turning point of the parable is the resourceful facing of the crisis mid-narrative. Again, the focus on individuals and dialogue to convey the message.

And he said also unto his disciples, There was a certain rich man, which had a steward; and the same was accused unto him that he had wasted his goods.

And he called him, and said unto him, How is it that I hear this of thee? give an account of thy stewardship; for thou mayest be no longer steward.

Then the steward said within himself, What shall I do? for my lord taketh away from me the stewardship: I cannot dig; to beg I am ashamed.

I am resolved what to do, that, when I am put out of the stewardship, they may receive me into their houses.

So he called every one of his lord’s debtors unto him, and said unto the first, How much owest thou unto my lord?

And he said, An hundred measures of oil. And he said unto him, Take thy bill, and sit down quickly, and write fifty.

Then said he to another, And how much owest thou? And he said, An hundred measures of wheat. And he said unto him, Take thy bill, and write fourscore.

And the lord commended the unjust steward, because he had done wisely: for the children of this world are in their generation wiser than the children of light.

And I say unto you, Make to yourselves friends of the mammon of unrighteousness; that, when ye fail, they may receive you into everlasting habitations.

He that is faithful in that which is least is faithful also in much: and he that is unjust in the least is unjust also in much.

If therefore ye have not been faithful in the unrighteous mammon, who will commit to your trust the true riches?

And if ye have not been faithful in that which is another man’s, who shall give you that which is your own?

The prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32) — The mid turning point; psychologically developed individuals; optional allegory.

And he said, A certain man had two sons:

And the younger of them said to his father, Father, give me the portion of goods that falleth to me. And he divided unto them his living.

And not many days after the younger son gathered all together, and took his journey into a far country, and there wasted his substance with riotous living.

And when he had spent all, there arose a mighty famine in that land; and he began to be in want.

And he went and joined himself to a citizen of that country; and he sent him into his fields to feed swine.

And he would fain have filled his belly with the husks that the swine did eat: and no man gave unto him.

And when he came to himself, he said, How many hired servants of my father’s have bread enough and to spare, and I perish with hunger!

I will arise and go to my father, and will say unto him, Father, I have sinned against heaven, and before thee,

And am no more worthy to be called thy son: make me as one of thy hired servants.

And he arose, and came to his father. But when he was yet a great way off, his father saw him, and had compassion, and ran, and fell on his neck, and kissed him.

And the son said unto him, Father, I have sinned against heaven, and in thy sight, and am no more worthy to be called thy son.

But the father said to his servants, Bring forth the best robe, and put it on him; and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet:

And bring hither the fatted calf, and kill it; and let us eat, and be merry:

For this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found. And they began to be merry.

Now his elder son was in the field: and as he came and drew nigh to the house, he heard musick and dancing.

And he called one of the servants, and asked what these things meant. . . . .

The rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31) — Drury sees the rich man being careless of the crisis before him in Lazarus.

There was a certain rich man, which was clothed in purple and fine linen, and fared sumptuously every day:

And there was a certain beggar named Lazarus, which was laid at his gate, full of sores,

And desiring to be fed with the crumbs which fell from the rich man’s table: moreover the dogs came and licked his sores.

And it came to pass, that the beggar died, and was carried by the angels into Abraham’s bosom: the rich man also died, and was buried;

And in hell he lift up his eyes, being in torments, and seeth Abraham afar off, and Lazarus in his bosom.

And he cried and said, Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus, that he may dip the tip of his finger in water, and cool my tongue; for I am tormented in this flame.

But Abraham said, Son, remember that thou in thy lifetime receivedst thy good things, and likewise Lazarus evil things: but now he is comforted, and thou art tormented.

And beside all this, between us and you there is a great gulf fixed: so that they which would pass from hence to you cannot; neither can they pass to us, that would come from thence.

Then he said, I pray thee therefore, father, that thou wouldest send him to my father’s house:

For I have five brethren; that he may testify unto them, lest they also come into this place of torment.

Abraham saith unto him, They have Moses and the prophets; let them hear them.

And he said, Nay, father Abraham: but if one went unto them from the dead, they will repent.

And he said unto him, If they hear not Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded, though one rose from the dead.

The unjust judge (Luke 18:1-7)

And he spake a parable unto them to this end, that men ought always to pray, and not to faint;

Saying, There was in a city a judge, which feared not God, neither regarded man:

And there was a widow in that city; and she came unto him, saying, Avenge me of mine adversary.

And he would not for a while: but afterward he said within himself, Though I fear not God, nor regard man;

Yet because this widow troubleth me, I will avenge her, lest by her continual coming she weary me.

And the Lord said, Hear what the unjust judge saith.

And shall not God avenge his own elect, which cry day and night unto him, though he bear long with them?

The publican and the Pharisee (Luke 18:9-14)

And he spake this parable unto certain which trusted in themselves that they were righteous, and despised others:

Two men went up into the temple to pray; the one a Pharisee, and the other a publican.

The Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself, God, I thank thee, that I am not as other men are, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even as this publican.

I fast twice in the week, I give tithes of all that I possess.

And the publican, standing afar off, would not lift up so much as his eyes unto heaven, but smote upon his breast, saying, God be merciful to me a sinner.

I tell you, this man went down to his house justified rather than the other: for every one that exalteth himself shall be abased; and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted.

The master and slave (Luke 17:7-10)

But which of you, having a servant plowing or feeding cattle, will say unto him by and by, when he is come from the field, Go and sit down to meat?

And will not rather say unto him, Make ready wherewith I may sup, and gird thyself, and serve me, till I have eaten and drunken; and afterward thou shalt eat and drink?

Doth he thank that servant because he did the things that were commanded him? I trow not.

So likewise ye, when ye shall have done all those things which are commanded you, say, We are unprofitable servants: we have done that which was our duty to do.

The rich fool (Luke 12:16-23)

And he spake a parable unto them, saying, The ground of a certain rich man brought forth plentifully:

And he thought within himself, saying, What shall I do, because I have no room where to bestow my fruits?

And he said, This will I do: I will pull down my barns, and build greater; and there will I bestow all my fruits and my goods.

And I will say to my soul, Soul, thou hast much goods laid up for many years; take thine ease, eat, drink, and be merry.

But God said unto him, Thou fool, this night thy soul shall be required of thee: then whose shall those things be, which thou hast provided?

So is he that layeth up treasure for himself, and is not rich toward God.

And he said unto his disciples, Therefore I say unto you, Take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat; neither for the body, what ye shall put on.

The life is more than meat, and the body is more than raiment.

Luke’s Sources for the Good Samaritan

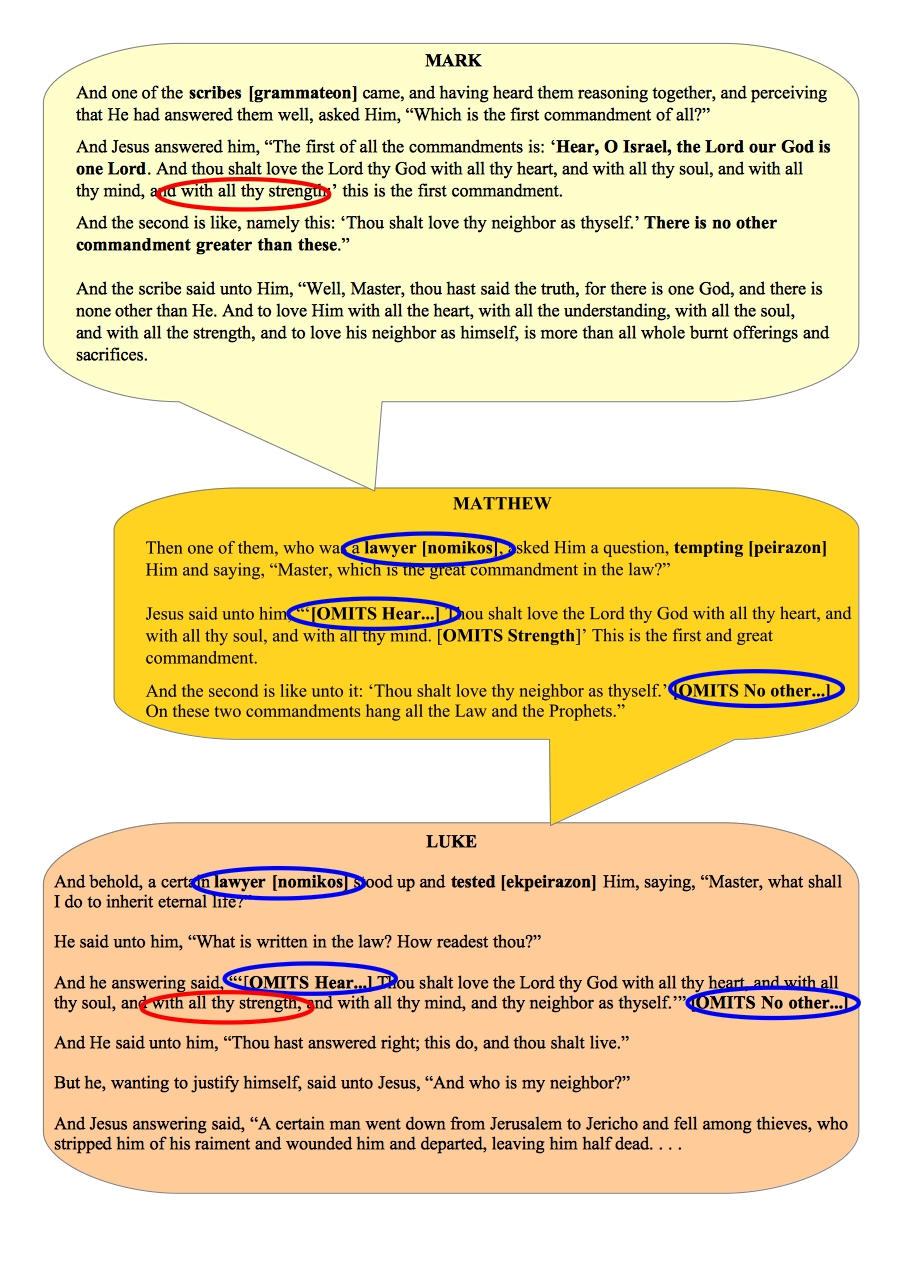

John Drury believes that he evolution of the Good Samaritan parable can be traced from literary sources: Matthew, Mark and 2 Chronicles. The sequence is this:

- Matthew adapted Mark’s version of the exchange.

- Matthew omits phrases from Mark’s account and exchanges Mark’s “scribe” with a “lawyer”.

- Luke built upon Matthew’s version although he did not forget Mark entirely. See the diagram below for the details.

- Luke characteristically added more interesting dialogue and interaction between Jesus and the lawyer.

- Luke further built on Matthew’s legalistic interpretation (“These are the greatest commandments and that’s that! What more is there to say?”) by taking the opportunity to stress the importance of kindliness and humanity (as he had done earlier in the Sermon on the Plain). Hence Luke introduces another parable about people, the Good Samaritan.

But why did Luke choose to have a Samaritan along with Jewish “clergy” as his foils?

But why did Luke choose to have a Samaritan along with Jewish “clergy” as his foils?

The answer very likely is to be found when we step back and take in Luke’s larger themes. For Luke the Jerusalem Temple is a central motif from the birth of Jesus to the final chapters of Acts. Luke’s story at one level is about the failure of the Temple and its eventual replacement by another service, one represented in the parable by the Samaritan. Recall from above the way Luke’s Samaritans take on the meaning of “the other”, those outside the Jewish nation. The parable is a microcosm of the larger theme of the failure of Judaism and its replacement by Christianity.

But what of the narrative details of the Good Samaritan story?

The Good Samaritan parable is essentially an illustrative story. As explained above this form of parable is typical from Luke. Such stories are familiar from the Old Testament.

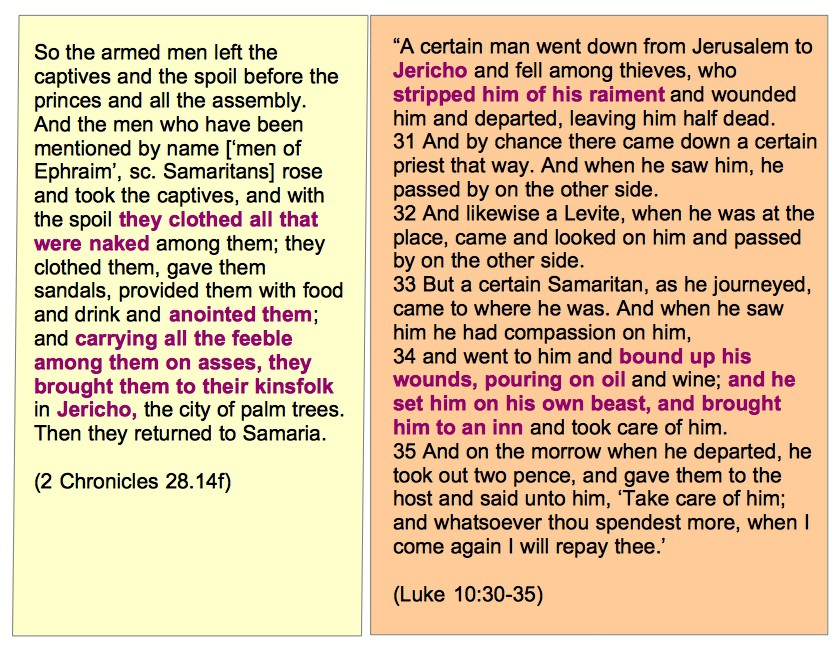

As we have seen, realistic stories as vehicles of ethics and theology were an older genre in the Old Testament than the historical-allegorical parables of Ezekiel. The Joseph and David sagas are examples. Esther and Judith show the genre flourishing in post-exilic Judaism. And from post-exilic Judaism comes the source of this good Samaritan story, a narrative in 2 Chronicles 28. (p. 134, my bolding)

God punished Ahaz, the king of Judah, because he burned incense under trees and on hills and for other wicked deeds. The punishment consisted of Syrian and Israelite armies waging war and slaughtering and capturing many tens of thousands of Ahaz’s troops. The king of Israel, Pekah, and his leading military officer, Zichri, led 200,000 captive women and children back to the gates of Samaria, the capital of the kingdom of Israel.

Before they entered the city, however, a prophet named Oded came out and castigated the Israelite king for his brutal treatment of his related tribe. So brutally had he treated Judah that God himself was now angry with him and his kingdom of Israel. Other leading men emerged from Samaria to add their voices to Oded and to demand that the captives be treated kindly.

Luke is not copying from 2 Chronicles word for word but he does appear to have adopted the significant ideas of

- clothing the naked,

- anointing,

- providing food and drink (at an inn in Luke),

- carrying the weak on asses

- and Jericho.

And for good measure

The parable contains twelve words which occur only here in the New Testament: a usual feature of L parables, attributable to their richness of detail. (p. 134)

I think this all adds up to a good case for the Good Samaritan along with other famous parables unique to Luke were the author’s own compositions. It is not likely that Luke was attempting to incorporate a popular orally transmitted tale supposedly from Jesus.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

But Q!

Good point! I’m not into Q myself and I can’t find much about it on Vridar because it isn’t a category and you can’t search for “Q” very effectively. And I don’t see a series on Mark Goodacre’s “The Case Against Q”. Am I missing anything?

OK, just figured out to search “The case against Q”. I see several posts there.

FWIW, I really dislike reading the King James Version. In small doses, it’s fine, but lots of it makes me annoyed.

I’ve not written much on Q partly because it’s far too complex a topic and there are already some excellent websites covering the arguments as I’m sure you know. To do justice to the arguments both for and against would require me to do far more intensive study and reading than I have allowed myself time for.

I’m obviously biased in favour of the arguments for literary relationships and intertextuality but at the same time I understand that presenting only one side of an argument (such as in this post) is really side-stepping the question of Q and not by any means refuting Q as an alternative.

Sorry about the 1611 quotations. I think I just grabbed that one after seeing the default NIV failed to convey some important distinctions in the original text. Normally I at least go for the 21st century ed of KJV if KJV at all. Will try to keep your disapproval in mind for next time! 😉

Whenever in any studies of Luke and/or Matthew the perspectives on the textual relationships to Mark and Q are missing, my interest in them is much diminished.

I don’t think you can get a clear view on the motives of the original authors of these gospel stories without discussing in detail what they did to these two sources as well.

Drury does not allow any room for addressing Q in the way I think you mean. He believes Luke used Matthew and Mark. No Q.

The Samaritans get slandered pretty badly in the Bible and in Rabbinical writings but there is evidence that the so called First Temple was in Samaria’s Mount Gerizim and not Jerusalem.

The “lost tribes” of the Bible were the Samaritans.

Actually, if you were to consider all the extra-biblical evidence we have, the earliest known temple would have been that in Elephantine, as the high priest there claimed it existed long prior to the Persian conquest of Egypt. In terms of the archaeological record, we don’t have any evidence of Solomon’s Temple (recall the “Second Temple” was built on exactly the same site to exactly the same specifications) or of the Elephantine temple that was destroyed by the Egyptians, and the evidence we have of the Samaritan temple places the initial building to early in the so-called Persian Period (and perhaps slightly before the time of “return” from exile) with a significant expansion occurring around the time of Antiochus III the Great. Moreover, according to Israel Finkelstein, the archaeological record seems to help identify anachronisms in the story of the building of the Second Temple that place the story to the time of Herod (or maybe slightly earlier in the late Hasmonean period).

My theory is that the Judaism of the Old Testament, and especially the Primary History, was essentially unknown prior to the Seleucid conquest of the region, that the fictional Solomon was an intentional reference to Ptolemy II, who was associated with the founding of the syncretic Yawheh cult, and that the destruction of the fictional Solomon’s Temple was an intentional echoing of Adam and Eve being cast out of Eden for disobeying Yahweh. What was Solomon’s “Original Sin”? He failed to build his temple where the original version of Deuteronomy appears to have mandated: Mount Gerizim. The whole point of the Primary History was to legitimize the Samaritan Temple as the proper central seat of cultic power in the region and to delegitimize the Ptolemies.

Some, including Thomas L. Thompson, would argue that the Samaritans only had the Torah, not the full Primary History, but that argument fails if you accept, as Thomas L. Thompson does, Calum Carmichael’s argument that Deuteronomy was written in part based on the stories of Israel’s first kings, which are found in Samuel and Kings (books that the Samaritans don’t have today). The obvious retort is that the Samaritans must have copied the Torah from the Jews in Jerusalem, but there is far more evidence to indicate that the folks in Jerusalem were the plagiarists. For example, the stories of David and Solomon are polemics against the Ptolemies, and the laws the Ptolemies (and David and Solomon) violated were honored by the Seleucids. A better explanation for the Samaritan’s lack of a Primary History outside of the Torah is that the latter books formed the seeds of the Samaritan Temple’s destruction by the Ptolemaic loyalists who became known as the Hasmoneans in that the latter books unintentionally allowed the Ptolemies to argue that Jerusalem was the proper seat of cultic power. The authors of the Primary History were far too subtle on the point that Yahweh’s covenants with David and Solomon were null and void because of David’s and Solomon’s violations of those covenants. As Thompson has argued, the kingdom of Judah was a reference to Ptolemaic Egypt, and based on that, my theory is that the authors, in arguing that the House of David (the House of Ptolemy) remained legitimate rulers of Judah (Egypt), merely intended to indicate that the Ptolemies remained rightful rulers of Egypt (and perhaps the offered a promise the Seleucids would not seek to overthrow Ptolemaic rule of Egypt).

As you can probably tell, I believe the Primary History originated as Seleucid propaganda, most likely in the time of Antiochus III, designed to legitimize the shift of cultic power in the region from Ptolemaic loyalists (in Judah) to Seleucid loyalists (in Samaria). The combination of the archaeological record and the extra-biblical written record (including Josephus) supports this interpretation of the nature and purpose of the Primary History, and that’s because my theory starts from such evidence instead of from the Primary History itself.