For all posts in this series: Roger Parvus: A Simonian Origin for Christianity

Previous post in this series: Part 12: A Different Perspective on the Corinthian Controversy (conclusion)

| We finally come to the question of how my Simonian hypothesis would deal with the inconsistent Pauline position regarding the Mosaic Law. Like resurrection, the Law was a subject about which Simon of Samaria’s teaching differed significantly from that of the proto-orthodox. So if the Paul who authored the original letters was Simon, we can expect to find in the canonical versions signs of proto-orthodox intervention aimed at the correction of his errors on that issue.

Most of what the Apostle wrote about the Law was in the context of its relationship to sin and justification. It is thought that Gal. 2:16 is the earliest mention in the letters of justification/righteousness/rectification (dikaioō; dikaiosynē) by faith apart from works of the Law. Teachers— again, apparently connected to the Jerusalem church—were pushing his Galatian faithful to receive circumcision and observe at least some parts of the Law. The teachers were likely preaching a justification that was in some way connected with the Law. The Apostle responded with a letter that put a different twist on this. |

Justification and Law in the Apostle’s gospel

Regarding justification by faith William Wrede long ago pointed out that:

The Reformation has accustomed us to look upon this as the central point of Pauline doctrine, but it is not so. In fact the whole Pauline religion can be expounded without a word being said about this doctrine, unless it be in the part devoted to the Law. It would be extraordinary if what was intended to be the chief doctrine were referred to only in a minority of the epistles. That is the case with this doctrine: it only appears where Paul is dealing with the strife against Judaism. And this fact indicates the real significance of the doctrine. It is the polemical doctrine of Paul, is only made intelligible by the struggle of his life, his controversy with Judaism and Jewish Christianity, and is only intended for this. (Paul, p. 123)

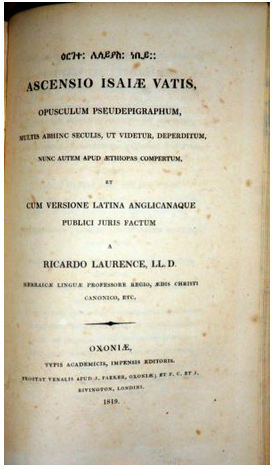

But if justification by faith was not at the center of the Apostle’s gospel, he did see it as at least a nonnegotiable implication. And this makes sense if, as I proposed in posts 7 through 9, the written source of his gospel message was the Vision of Isaiah. For the Vision foretells that preachers will be sent out into the whole world (Ascension of Isaiah 9:17, in the L2 and S versions), but does not say that the Law or Law observance will be part of what they preach. The Law is not mentioned at all in the Vision nor does it say anything about a distinction of Jews from Gentiles. It condemns the spirit rulers of this world and offers a life in heaven to their subjects, but gives no special prerogatives to the Jewish ones. The idea that the message must first be offered to Jews and only afterwards to Gentiles is absent.

But if justification by faith was not at the center of the Apostle’s gospel, he did see it as at least a nonnegotiable implication. And this makes sense if, as I proposed in posts 7 through 9, the written source of his gospel message was the Vision of Isaiah. For the Vision foretells that preachers will be sent out into the whole world (Ascension of Isaiah 9:17, in the L2 and S versions), but does not say that the Law or Law observance will be part of what they preach. The Law is not mentioned at all in the Vision nor does it say anything about a distinction of Jews from Gentiles. It condemns the spirit rulers of this world and offers a life in heaven to their subjects, but gives no special prerogatives to the Jewish ones. The idea that the message must first be offered to Jews and only afterwards to Gentiles is absent.

One could easily conclude that if the Vision doesn’t require circumcision or Law observance as conditions for liberation from the rulers, it is wrong for preachers of the gospel to require such. Apparently all that is required to benefit from the preached message is to believe it and, while waiting for the imminent destruction of this world, to conduct oneself in a way pleasing to the God who graciously initiated the rescue.

Moreover, in the Vision the sinfulness that is spotlighted is that of the rulers of this world. It is their pride that God forcefully condemns. He sends his Son to

judge and destroy the princes and angels and gods of that world, and the world that is dominated by them. For they have denied me and said: “We alone are and there is none beside us.” (Ascension of Isaiah 10:12-13).

In the Vision men come across not as the guilty, but as the victims. Their plight is to live in a dark world run by rulers whose “envy of one another and fighting…” make it a place where “there is a power of evil and envying about trifles” (Ascension of Isaiah 10:29). The “angels of death” (10:14) keep those who have died locked in Sheol until the Son comes to free them.

In Galatians a similar emphasis has been noted by some scholars:

The redemption is, according to Paul, in a phrase which is brief and yet exact, release from the misery of this whole present world (Gal. 1:4). Every other conception of it, even release from sin, would be too narrow. The character of this present world is determined by the fact that men are here under the domination of dark and evil powers. The chief of these are the flesh, sin, the Law and death. (William Wrede, Paul, p. 92)

For Paul, the problem that needs to be addressed is not so much ‘sins,’ transgressions of divinely given commandments, as Sin, a malevolent enslaving and godlike power under which all human beings are held captive. (Martinus C. de Boer, Galatians: A Commentary, p. 35)

So it may be that the Vision of Isaiah holds the key to a correct grasp of what Paul meant by “justification.” Scholars have always had a hard time explaining that doctrine. A big part of their problem may be their belief that God and men were the parties at odds. Justification becomes easier to understand if God’s beef was with the sinfully proud spirits who ruled the world. In this case the Son’s intervention in the world not only vindicates God vis-à-vis these pretentious rulers, it also vindicates men in regard to them. God, by initiating the destruction of the world and its rulers, has in effect acquitted their subjects. His condemnation of the rulers has freed those they heavy-handedly ruled. Continue reading “A Simonian Origin for Christianity, Part 13: Simon/Paul and the Law of Moses”