This post is based on the theme of a chapter in St. Paul versus St. Peter: A Tale of Two Missions by Michael Goulder. I depart from Goulder’s own presentation in one significant respect: Goulder wrote as if 2 Thessalonians were a genuine letter by Paul (in which Paul writes about the future in a way he was never to repeat); I treat the letter as spurious (following many scholars in this view). At the end of the post I introduce an alternative scenario that might apply if more critical scholars are correct and the letter should be dated to the second century.

2 Thessalonians appears to be a letter written by Paul. It disarmingly warns readers to be on guard against letters that appear penned by “himself” yet are in fact forgeries. The letter proceeds to warn readers not to be misled by preaching that the Kingdom of God was “at hand” but that a sequence of events had to happen first. One must expect a delay in the coming of the end.

Now we request you, brethren, with regard to the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ and our gathering together to Him, that you not be quickly shaken from your composure or be disturbed either by a spirit or a message [word] or a letter as if from us, to the effect that the day of the Lord has come.

Do you not remember that while I was still with you, I was telling you these things?

And you know what restrains him now, so that in his time he will be revealed. For the mystery of lawlessness is already at work; only he who now restrains will do so until he is taken out of the way.

Then that lawless one will be revealed whom the Lord will slay with the breath of His mouth and bring to an end by the appearance of His coming (2 Thess. 2:1-8 NASB)

How could anyone have believed that “the day of the Lord” had already come? Goulder’s explanation:

The idea has gained force in three ways:

- Christians cry it out during services in moments of ecstasy (by spirit);

- they appeal to the Bible (by word), perhaps especially Malachi 4.5, ‘Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes’;

- and a letter has been received claiming to be from Paul.

(p. 85. My formatting. Goulder discounts the likelihood of forgeries on the assumption that the letter was written at a time when churches were very small and carried and authenticated by well-known persons.)

So let’s see how the author of this letter, the one writing in the name of Paul, introduces and sets out his view of prophecy to the churches.

He divides the prophesied scenario into three phases. One of these is the “here and now”; the remaining two belong to the future.

1. “Now is the time of pause”

The mystery of lawlessness is already at work. The world is full of cruelty and evil. Christians are being persecuted, as was pointed out in the preceding chapter. There is a force that is restraining this evil. It is not yet removed but it will be when time has come for the next phase.

2. “Next will come the revealing of the man of lawlessness”

The power of Satan will be unleashed when the terrifying “son of perdition” is revealed and proclaims himself to be God, sitting in the temple of God. There will be great signs and wonders. This will be the darkest hour before the dawn.

3. “Finally, he will be destroyed”

This happens when Christ comes. So Christ cannot have come now. The day of the Lord is not here yet. It is “obviously” future. To think otherwise is a “strong delusion”.

The Source of the Man of Lawlessness Prophecy

Where did all of this come from? Goulder believes the author (whom he takes to be Paul) took it straight from the Book of Daniel.

In the first chapters of Daniel the Jews are persecuted. (So also, it seems, are the Christian readers of 2 Thessalonians.) Daniel and his colleagues themselves were thrown into lions’ dens and fiery furnaces. Then in chapter 9 Daniel confesses in prayer that

All Israel has transgressed thy law (Dan. 9:11)

The angel Gabriel comes to explain to Daniel what is happening and what to expect. Angelic powers are in conflict and those from God are even being held back by opposing spirits for a time. But God’s angels do prevail in the end and His will is carried out. A great and terrible king will arise on earth who will stop the Temple sacrifice and set up “the abomination of desolation”. The figure

will exalt himself and magnify himself above every god, and shall speak astonishing things against the God of gods (Dan. 11:36)

But he will be destroyed and then will come the resurrection (Dan. 11:45; 12:2).

The spurious letter draws upon the prophecies in Daniel to overturn the teaching that the Day of the Lord has come. It teaches that we are living in only the first stage of evil time. There is yet to come a terrible event that will be followed by the coming of the Lord with judgement.

After Paul came the Gospel of Mark. This gospel appears to carry several marks of Paul’s influence. What follows is another one — or an influence of a letter in his name — that is suggested by Goulder.

The Gospel of Mark

In the thirteenth chapter of the Gospel of Mark Jesus delivers his famous prophecy of the end times. It is well known today among evangelicals, fundamentalists and a host of cults and sects.

Mark puts the prophecy in the mouth of Jesus but the language and thought are close to what we have read in the forged letter of Paul, 2 Thessalonians.

Take heed that no one leads you astray. (Mark 13:5)

Do not be disturbed [cf shaken in mind/composure]: this must take place but the end is not yet. (Mark 13:7)

The evils of the age are listed and then the verdict delivered:

This is the beginning of birth pangs. (Mark 13:8)

The same three-phase pattern of the 2 Thessalonians prophecy is found here:

- Phase 1: There are the present sufferings that must happen

- Phase 2: Then will come the “abomination of desolation” — then those who see this must flee. . . Greater dangers follow.

- Phase 3: After those days, after that tribulation, the sun will be darkened . . . then they will see the Son of Man coming in judgement and the resurrection follows (13:24ff)

The Mark 13 prophecy contains many allusions to the Book of Daniel. Goulder adds:

The only section of the chapter which does not have a lot of Daniel and Thessalonians behind it is the persecution paragraph, 13:9-13; and here the details are strongly reminiscent of Paul and his friends. (p. 88, my emphasis)

- You will be beaten in synagogues (Mark 13:9)

- Compare Paul’s Five times I have received of the Jews forty lashes save one. (2 Corinthians 11:24)

- You will stand before governors and kings (Mark 13:9)

- Compare Acts 23-26 and Paul before Felix, Festus and Herod Agrippa II

- The gospel must first be preached to all nations (Mark 13:10)

- This reflects Paul’s personal mission

- Don’t worry when called upon to speak when on trial since the Holy Spirit will speak through you (Mark 13:11)

- Compare the eloquence of Stephen and Paul when on trial.

- Brother shall deliver up brother to death (Mark 13:12)

- Does this echo Paul’s martyrdom — 1 Clement 5 (from 90s CE?) says Paul’s death was caused by Christian envy.

- You will be hated by all because of My name (Mark 13:13)

- Pious Jews, according to Acts, respected the Jerusalem Christians, but Paul was hated.

Goulder:

The cumulative effect of these parallels is to suggest strongly that Mark has little or no tradition of what Jesus actually said about the future.

He has a tradition, and it is the Pauline tradition [= 2 Thessalonians], embattled with the Petrine already doctrine. That tradition affirmed robustly that the kingdom could not have come yet, because scripture said not. Daniel had laid out three phases. . . . . Mark amplified that tradition, and ascribes it to the Lord himself . . . . (p. 88, my formatting and bolding)

The Gospel of Mark, Goulder argues as do many of his peers, was written after the desecration of the Temple and the Jewish War against Rome. Any moment, goes the theory, the “abomination of desolation” was about to be set up and “phase 2” begin.

This is another common perception I have difficulty accepting. The imagery in Mark, including the imagery of the miracles, are evidently allegorical or symbolic in some fashion when carefully analysed. Karel Hanhart follows this clear literary characteristic of Mark’s gospel right through to the scene of the empty tomb: he finds even that hewn out rock to be a midrashic adaptation of the Septuagint’s (Greek) passage of the desecrated temple being compared with a rock tomb (Isaiah 22:16). (See Was the Empty Tomb Story Originally Meant to be Understood Literally?) The cosmic imagery of the end-time in Mark 13, with falling stars and darkened sun and so forth, is taken from OT prophetic passages — e.g. Isaiah 13 — depicting the coming judgment of God and the end of great kingdoms and cities. I see every reason to think that the same imagery in Mark 13 should likewise be understood symbolically. In the year 70 God cast out the Jewish tenants of his vineyard and gave possession of his realm to the church.

If so, there is no need to tie the date of the Gospel of Mark to the year 70 or thereabouts. Its apocalyptic character may still have been relevant quite some years after that time.

The expected coming of the kingdom (Phases 2 and 3) did not eventuate as Mark is thought to have predicted — assuming the literalist interpretation of the apocalyptic imagery in Mark 13.

So after the Gospel of Mark, according to Goulder’s timeline, comes the Book of Revelation.

The Book of Revelation

Goulder writes of the author of Revelation as another “Pauline”. Ouch! I have tended to see (with Couchoud and others) Revelation as opposed to the theology of Paul. See, for example, The Christ of John’s Revelation — Nemesis of Paul’s crucified Christ. This is probably a good time to reflect upon the series by Roger Parvus with his demonstrations of the “zigs and zags” that we see in the wake of an attempt to make the original Paul fit for orthodoxy.)

But we’ll continue with Goulder’s case for now.

Revelation’s prophetic scenario continues with the prophetic phases. These are said to coincide with Mark’s phases:

Phase 1, the Now: compare Revelation 6 and the four Horsemen bringing war, disease, famine, death.

Phase 2, the Man of Lawlessness of 2 Thess. 2: compare Revelation’s Beast being worshiped and oppressing the church.

Phase 3, the slaying of the Man of Lawlessness and the resurrection: compare Revelation’s next two phases — one of the bowls of judgment bringing blood and darkness and death to the wicked and the other of the White Horse and the resurrection of the dead.

Goulder sees one other little modification to Revelation’s Phase 1 that may be of major significance.

The gap of a half hour silence

When the Lamb broke the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven for about half an hour. (Revelation 8:1)

Following this half hour silence are a string of woes “which bear a marked resemblance to events which took place in the 70s. (p. 90)

- The “terrifying comet” in 73 (cf the great star that fell to earth in Rev. 8:10f)

- The eruption of Vesuvius in 79 (cf Rev 8:8f and the smoke from the pit and torments upon mankind in 9:106)

- In 80 “the rumour went round that Nero had risen from the dead, and was leading the armies of Parthian cavalry from across the Euphrates” [See Dio Cassius 66.19] — compare Rev. 9:13-19.

The half hour gap was to account for the apparent delay in the expected appearance of the Man of Lawlessness and return of Christ that Mark had led readers to expect. The emperor who assumed power for the ten years after Nero (69-69) was Vespasian but he did not behave like the prophesied wicked monster. So perhaps Titus, his son, was to be the fulfilment. So there is a half hour gap in heaven between the Trumpets (the difficult “now” time) and the Seals (the rise of the great evil).

In this way the Lord’s prophecy of the end of history in mark 13 is subtly extended by a decade: so subtly that the Seer’s handiwork has hardly been noticed from that day to this. (p. 90)

I expect many readers will have their own reservations about Goulder’s explanation of Revelation’s half hour silence.

Is it really possible that. . . . ?

What is interesting is the possibility that all the Hal Lindsay and evangelical and fundamentalist and cultic end-time enthusiasts are following the prophetic tradition that was slipped into the Church by a forged letter.

–0O0–

An alternative

Goulder’s scenario rests upon the message of 2 Thessalonians being embraced by Paul’s early churches and taken over by the author of the earliest gospel. What if 2 Thessalonians were in fact penned much later? Its prophecy still seems to be generalized enough to indicate the Mark 13 prophecy was unknown to its author.

What if 2 Thessalonians were not written until much later? The fourth verse of its first chapter informs us that its audience was being persecuted.

Therefore, we ourselves speak proudly of you among the churches of God for your perseverance and faith in the midst of all your persecutions and afflictions which you endure. This is a plain indication of God’s righteous judgment so that you will be considered worthy of the kingdom of God, for which indeed you are suffering. For after all it is only just or God to repay with affliction those who afflict you,and to give relief to you who are afflicted and to us as well when the Lord Jesus will be revealed from heaven with His mighty angels in flaming fire, dealing out retribution to those who do not know God and to those who do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus. These will pay the penalty of eternal destruction . . . . (2 Thess. 1:4ff NASB)

When were the Christians persecuted in such a way? We can discount the theological romances of Acts. Second Temple Judaism was, one might say, “a very broad church”. Diversity of views were what made it what it was. Not that they all necessarily loved one another but can we really imagine under the “Pax Romana” Jewish bands being given permission by the state/priests to go out and kill Christians? Paul’s teachings, as we have seen in several series of posts here (e.g. Novenson’s) were as Jewish as any other Jewish sect of the period. The Neronian persecution was quite likely a myth, but if real, it was localized and over almost as soon as it started and certainly had no impact upon Thessalonian Christians. The Diocletian persecutions have been shown to have been another myth, too.

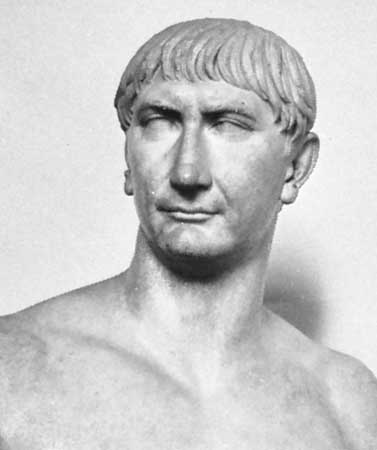

Our first evidence for the “persecution” of Christians comes from the turn of the first century and a series of letters between the Roman emperor Trajan and Pliny, who at the time (112) was the governor of Bithynia and Pontus, in modern-day Turkey. . . . The fact that Pliny has to make inquiries about [how to treat Christians] indicates that, before this point, there were no measures in place for the treatment of Christians. (Candida Moss, The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom, pp. 139-140.)

I quote below J. V. M. Sturdy’s arguments for dating 2 Thessalonians no earlier than the reign of Trajan. Back in 1928 Delafosse (Turmel) published an argument that the “Man of Lawlessness” in this letter was Bar Kochba, the Jewish rebel leader (“messiah”) who apparently also persecuted Christians in Judea in the time of Trajan’s successor, Hadrian. See Identifying the “Man of Sin” in 2 Thessalonians. Some of us might now be wondering about Herman Detering’s argument that if not the Gospel of Mark, then certainly his prophetic chapter 13 was either added (or expanded) in the light of the events of that war. See Little Apocalypse and the Bar Kochba Revolt.

Now this opens up a whole new set of questions and possibilities for the dating of the gospels. I’ll leave readers to ponder the possibilities and problems with all of this.

.

J. A. T. Robinson on the date of 2 Thessalonians:

II Thessalonians. To go into the challenges that have been made to the authenticity and integrity of this epistle and to its order in relation to 1 Thessalonians would take us far afield. The arguments are set out in all the commentaries. Suffice it here to say again that, after full examination of all the theories, both Kummel . . . and Best . . . come down decisively in favour of the traditional view that Paul wrote II Thessalonians, with Silas and Timothy (1.1), from Corinth within a short time of 1 Thessalonians, either late in 50 or early in 51.

The hypothesis of pseudonymity, despite the authentication of the personal signature in 3.17, would require a date at the end of the first century. Yet, as Kummel says, 2.4 (‘he … even takes his seat in the temple of God’) ‘was obviously written while the temple was still standing’. [The authenticity of II Thessalonians is defended by F. W. Beare, IDB IV, 626, even though he would question both Ephesians and I Peter and is doubtful about Colossians.] There is no sound reason for not accepting the usual dating. . . . (John A. T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament, pp.53f. My formatting)

J. V. M. Sturdy on the date of 2 Thessalonians:

2 Thessalonians is equally pseudonymous.* The decisive point here is that 2 Thessalonians has so many similarities with 1 Thessalonians in the midst of so many Significant differences that one is almost obliged to consider the theory of pseudonymity. [Cf. Perrin and Duling (1982: 208).] 2 Thessalonians contains many un-Pauline phrases and stylistic peculiarities. Krodel has advanced the interesting suggestion that 2 Thessalonians seems to imitate what may itself be an interpolated thanksgiving in 1 Thessalonians 2:13-16. [Krodel (1978: 77-79).]

There are substantial theological differences between the two letters. In 1 Thessalonians 4:15 the parousia is held to be imminent. 2 Thessalonians 2:1-12 seems to alter this perspective when it describes a sequence of events that must be accomplished before the parousia, as if the author is conscious of the fact that events had not happened as Paul had originally predicted. Yet, on the timescale proposed for 2 Thessalonians by those who claim it is a genuine letter, it is followed by 1 Corinthians 15 where the imminent perspective is repeated.

Also difficult to reconcile with the genuine Paul is the fact that in 2 Thessalonians 1:5-10 persecution is promised to the persecutors in a strikingly vindictive assertion of divine retribution. Perrin and Duling also detect a christological difference between the two letters in the tendency to equate God and Christ in terms of the theology of divine action. [Cf. Perrin and Duling (1982: 208).]

I therefore treat 2 Thessalonians as a product of the Pauline School and think it was written in deliberate imitation of 1 Thessalonians. Its date is probably quite late. The letter implies a general persecution of the Christians by the Romans. Given that there was no Domitianic persecution in 96 CE, this brings us to the second decade of the second century like 1 Peter and Revelation (or even later than this). Vielhauer says before c.110 CE because 2 Thessalonians is cited in Polycarp; but if Polycarp is either 135 (Harrison) or from the third century (my view), there is no problem in accepting the validity of this reference. I date the letter to the period 120-30 CE and believe that it reflects the Trajanic persecution, as do other texts from around this period.

*

This point is acknowledged by Evanson (1792); Schmidt (1801: II. 3); Eichhorn (1810-27); de Wette (1826; but he was more reserved in subsequent editions. and defended genuineness from the 4th edition onwards); Schrader (1835: V.41ff.); Mayerhoff (1838); Kern (1839); Lipsius (1854); van Manen (1865); Baur (1845: 480-92; 1855; 1866-67: 480); Bauer (1852); Lipsius (1854); Weisse (1855); Noack (1857: 313ff.); Volkmar (1867: 114); Hausrath (1868-74: II. 600); Hilgenfeid (1862; 1887: 642-52); Steck (1883); HoItzmann (1885: 229-30); Pfleiderer (1873: I. 29); Vies (1875); Hausrath (1868-74: II. 600); Bahnsen (1880: 681-705); von Soden (1885b); von Weizsacker (1886: 190.258-61); Spitta (1889: 497-500); Bruckner (1890: 253-56); Martineau (1890: 555); Rauch (1895); Wrede (1903); Hollmann (1904); Wendland (1912); Loisy (1922: 135; 1935: 89f.); Jillicher and Fascher (1931: 67. not in earlier editions); Barnes (1947: 224f.); Bultmann (1958: 191, by implication): Braun (1952-53; 1962: 205-209); Masson (1957: 9-13); Schoeps (1961: 51); Fuchs (1960); Eckhart (1961); Day (1963); Bornkamm (1970: 243); Wurzburg (1969: 96-105); Pearson (1971); Marxsen (1964); Giblin (1967); Trilling (1980); Krodel (1978: 77-79); Schenke and Fischer (1978: 191-98); and Beker (1991: 72-75). Davidson (1868) held that 2 Thessalonians had a genuinely Pauline basis but contained later interpolations; Schmidt (1885) championed a similar view. Spitta (1893: 109-54, 497ff.) held that Timothy wrote the letter.(J. V. M. Sturdy, Redrawing the Boundaries, pp. 58f. My formatting)

.

On there being no Domitianic persecution:

Thompson (1990). See also Collins (1984) and d. the following comment from a secular historian:”No convincing evidence exists for a Domitianic persecution of the Christians” (Jones 1992: 117). Earlier scholars who discuss the Domitianic persecution include Hartman (1907); Bergh van Eysinga (1908); Lelong (1912:xxxi); Canfield (1913: 72-85); Merrill (1924: 148-73); Henderson (1927: 45); Last (1937); Enslin (1938: III, 313, 325); Milburn (1944-45); Knudsen (1945); Beare (1947: 32); Moreau (1953; 1956: 36-40); Sparks (1952: 142); Ste Croix (1963); Barnes (1971: 150); Sweet (1979: 24£); and Downing (1988). Those who accept the hypothesis of a Domitianic persecution include Smallwood (1956) and Syme (1988: 29). Jaubert (1971: 69) admits there was no persecution under Domitian but still assigns 1 Clement to 96. (p. 95)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

About the question of markian dependence from Paul, I derive this too audacious and curious inference:

Mark 14:48 :

Mark 15:27 :

1 Cor 9:21 :

It’s possible to see an irony in Mark 14:48 and/or 15:27 that brings to the extreme paradox the point by Paul in 1 Cor 9:21 (and in Gal 2:20, ”crucified with Christ”):

the outsiders see two bandits, i.e., outlaw, but only insiders can see that with Christ are crucified oi hanomoi, ”without law”, the true Christians Torah-free. The Jesus enemies see him as a mere bandit outlaw, but he is free-Torah. Like Paul.

The problem is that there is no clue that the two bandits are positive figures, no clues of their being gentiles (because otherwise my guess would be more strong).

There is a clue. It is in Mark 10:35-40. The two bandits are as much faint echoes of James and John as Simon of Cyrene is of Simon Peter.

On the other hand (or in conjunction with the above?), we have the fact that Mark regularly alludes to OT passages without drawing explicit attention to them (Mark 15:28 is a gloss).

1. What are the implications for dating “Pauline” letters re the reported order of Caligula to set up his statue in the Jerusalem Temple?

2. Does not “Daniel” have VERY great importance to the chronology, dating and content of the canonical gospels, “Revelation” and some epistles?