We have deep depth.*

In a recent interview focused on Jesus mythicism, Dale Allison said:

Re memory: My wife and I disagree about our memories all the time. About things that happened years ago, months ago, weeks ago, days ago, or hours ago. It happens so often that it’s a standing joke, and we’ve reconciled ourselves to the fact that, when there is no third witness, we can’t figure out who is right and who is wrong. Heck, sometimes we both must be wrong. But we’re not mythographers, because what we are almost always misremembering is related to something that happened. It’s faulty memory, not no memory. (emphasis mine)

He likens the issue of reliable memory in Jesus studies to the problem of how Socrates was remembered differently by his contemporaries. But Socrates, he asserts, still existed. He then likens the problem of the historical reliability of the New Testament to a court case. (I refer to Neil’s recent post on the Criterion of Embarrassment as to why a court case is a terrible example.)

It’s also worth thinking about conflicting testimony in court. When people disagree on their recollections of an accident or crime scene, we don’t conclude there was no accident or no crime. We just say that memories are frail and then try to find the true story behind the disagreements. I’ve argued in Constructing Jesus that we can try a similar approach with the sources for him.

That concept — finding “the true story behind the disagreements” — leads us to the notion that the gospels (and Paul) provide the gist of the stories about Jesus. They can tell us, Allison imagines, what Jesus was really like, even if the details have been changed over time because of our “frail” memory.

It’s like déjà vu all over again.*

Even fabricated material may provide a true sense of the gist of what Jesus was about, however inauthentic it may be as far as the specific details are concerned.

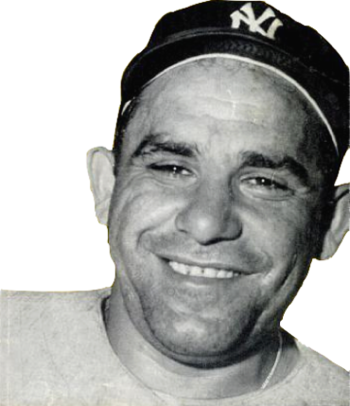

Or as Yogi Berra put it:

I really didn’t say everything I said.

I’d like to believe that Yogi really said most of the things he said, but I also know that we humans love our myths. And one of my favorite myths is that Yogi is some sort of unwitting Zen master who spontaneously utters cryptic, timeless Yogi-isms: nuggets of wisdom wrapped in apparent nonsense.

You can observe a lot by just watching.*

As an American I can’t help but have a fondness for the myths of the Founding Fathers. In grade school I recall drawing in crayon a young George Washington, standing next to a fallen tree, holding an ax, and saying, “I cannot tell a lie.” I’m pretty sure he was wearing a powdered wig in my rendition. Naturally.

We know that Washington almost certainly never chopped down a cherry tree and then ‘fessed up to his dad. But does the gist of the story reveal something about George’s character? In other words, do the myths of Washington provide a window into the past? — the echo of a “memory” of our first President?

The future ain’t what it used to be.*

Suppose we’re living 10,000 years from now on a new planet — after a devastating war and and ensuing “dark age.” Our knowledge of the past is incomplete. All we know about George Washington is contained in the fragments we have from children’s books printed in the 19th century.

What could we say that we probably know about old George? Could we assume that the story about cutting down the cherry tree, although fabricated, “may provide a true sense of the gist of what Jesus Washington was about, however inauthentic it may be as far as the specific details are concerned“? That’s one possible interpretation.

However, we would also be aware that the claim of his unfaltering honesty could have arisen from Washington’s carefully crafted public persona. The badge of honesty may have resulted from a successful propaganda campaign. That is, we may be able to say that people in the age in which the stories were written “remembered” Washington as an honest man, but we may not know the real man.

A third alternative, to which I subscribe, is that we don’t really know what the story means until we know why it was written. And there’s good evidence that both this story, along with the story of Young George and the Colt, arose out of a desire to instill virtue in children by means of examples. In short, the impetus behind these myths comes not from a shared social memory of Washington, but from a strong desire to teach children to tell the truth.

To assume without physical evidence, while relying completely on fragmentary, secondary, literary evidence, that a story reflects a memory is begging the question.

It’s pretty far, but it doesn’t seem like it.*

The problem I have with a lot of these new “memory” studies, popping up like so many mushrooms in the soft, pungent muck of NT scholarship, is the frequent assumption that each passage in the gospels or in Paul’s letters that alludes to something Jesus did or said is a memory of the authentic Jesus. Yes, it might be “refracted on a trajectory” or distorted by “frail memory.” Hell, it might even be true fiction! As Anthony Le Donne wrote of Allison’s work:

[W]hat Constructing Jesus will be celebrated for 50 years from now is Allison’s thesis that even haggadic fictions can betray memory in ways that are helpful to the historians.

Before reflecting upon the reasons for the story’s existence, they start thinking about memory. Even after dispensing with historicity, they insist that some kernel of truth is hidden within.

It gets late early out here.*

Just what in the world is going on here? L. Michael White in Scripting Jesus hit the nail on the head.

In part, the problem here is the term “memory.” For many people working in the area of Gosple studies, it is taken to imply an “authentic kernel of teaching or a historical episode” that is preserved more or less without variation in later oral reports. But is that really what is reflected in studies of oral tradition? Even Kenneth Bailey‘s work, which served as the basis for [James D.G.] Dunn’s model [in Jesus Remembered], suggests a rather different notion of memory. (White, p. 100, emphasis mine)

White recounts Bailey’s description of tales told in gatherings of modern villages in the Middle East. But while it’s true that Bailey himself wrote about “informal, controlled oral tradition,” passed down from generation to generation, his actual research revealed something else.

On the other hand, closer examination of Bailey’s own sources shows that many of these stories as preserved are far removed from early authentic accounts of what really happened. Instead, they were often episodes or stories that were shaped through the later experience of those village communities and then passed down in this later, evolved form.

In one case, the story discussed by Bailey even reflects a conscious and collective effort of villagers to concoct a fictional account to cover up an accidental death.

In another, the original episode was fancifully embellished into a story of a Christian preacher’s nighttime encounter with a band of robbers, who then converted to Christianity. Such elements never appear in the earliest version, yet it is this fanciful version that is “remembered” in later storytelling.

In a third, the traditional Bedouin folk tale was intentionally altered in oral presentation by one respected village elder in order to make a new didactic point; meanwhile, the villagers knew quite well what he was doing. Yet both the original version and the altered one were preserved in later storytelling. (White, p. 101, my bold emphasis and reformatting)

It ain’t over ’til it’s over.*

Note well that the villagers now “remember” a false version of the story. What is now true for them is a story that fulfills a purpose different from history. Quoting White again:

What this all means is that, although stories were indeed preserved and passed on in the life of these villages, they usually represent some sort of “constructed memory” that reinforces the identity and self-consciousness of the community, not just “what really happened.” (White, p. 101, emphasis mine)

What’s missing from the much of the research in memory studies within NT scholarship is the acknowledgment that the majority (if not all) of the stories in the gospels are almost certainly “constructed memories,” generated and maintained by communities of worshipers. They are not memories that were distorted over time by human frailty; they are fictions that reinforce community identity. As such, we cannot apply a magic lens to rectify the distorted image. The true story behind the fiction has been erased, or it might never have existed in the first place.

Instead, we need some method or methods by which we can separate what has been constructed from what has been left intact. But even that statement presupposes that the collection of stories must contain some truth, and we simply don’t know that.

Allison again:

You can doubt everything if you want to. It’s a question of what’s more plausible, and it’s my sense of things that positing an historical Jesus leaves us with fewer problems than the alternative.

I don’t doubt because I “want to,” but because honest analysis of the facts leads me there. That said, I will agree with part of that last sentence. The only valid argument left to Jesus historicists is whether the historical model is more plausible. But that’s cold comfort, since it could easily lead us to a Jesus who “probably existed,” but whom we know nothing about.

- Quotes attributed to Yogi Berra

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Memory doesn’t happen in some foolproof vaccuum inside our brain, its creation is subject to all of the failures of reasoning and cognitive biases that have shaped cognition itself (it might be more accurate to say that our brains are nothing but cognitive biases). Case in point: Memories can be easily fabricated, especially in groups. Considering that group dynamics are how a lot of religions get formed and spread, the hypothesis that many, if not all, of the “memories” of Jesus were fabrications should carry a bit more weight.

James Dunn wrote

It seems to me that it’s easy to explain. The earliest believers understood the resurrection as a part of the coming of the kingdom of God. They preached it that way and the language inevitably got attributed to Jesus. Whether the historical Jesus spoke about the “kingdom of God” a little, a lot, or not at all, I would expect that any stories about him would be filled with it because the stories were being told to propagate belief in the resurrection and that’s how the resurrection was understood.

Even if there was a historical Jesus, the gospels only contain a tiny portion of what he said and did, and the portion that they contain is only going to be that portion that is useful in explaining the resurrection. Even if the gospels somehow contain genuine memories, it’s not the gist of the historical Jesus, but that portion of him that fits with the belief in the resurrection.

ALLISON

We just say that memories are frail and then try to find the true story behind the disagreements.

CARR

Yes, when Luke disagrees with Mark (or Matthew or Q or whatever), what happened was he just plain forgot what was written in the document he had in front of him and tried his best to reconstruct it (rather than just read it again)

Similarly, when Matthew wrote about Jesus being born in Bethlehem, it was because he had simply forgotten that Jesus came from Nazareth.

And when Paul doesn’t mention things Jesus did, it was because everybody already knew all about Jesus but they simultaneously had frail memories of what they all knew all about.

But , despite their ‘frail memories’, Paul never gives them a gentle reminder of a parable or a healing , because why waste paper writing about what everybody knew. Much better to fill up the 16 chapters of your *enormous* letters with words of praise of love or reminders that only one person can win a race.

Mainstream Biblical studies is an endless source of amusement.

Exactly.

Because if Jesus and the apostles actually existed, why in the world would the apostles think their only truly crucial function would be to accurately record and preserve the exact facts and words of wisdom of the most important earthly being the world had ever seen? It’s not as if someone’s eternal salvation might depend on it, after all.

And why should we expect them to have coherent memories? It’s not as if they were supposedly right there in the same room as the guy, hearing the same words, stories, and history. Or able to ask one another if they all heard the same thing. It can get really noisy, you know, in the Levant what with all the jet traffic and boom boxes blaring. Super easy to mistake the word ‘Bethlehem’ with the word ‘Nazareth’. That’s just a trivial mistake.

What is important to remember is that they got the big historical events recorded accurately. Like the facts about the Sermon on the Mount, perhaps the most influential of the teachings of JC. A huge gathering of thousands of people, hearing a groundbreaking and revolutionary gospel, guaranteed to be the talk of the county for months. Obviously, the fact that no account by any independent historian survives or is even referenced must be due to selective suppression by the … um.. by…. by the Church. Yeah, that’s the ticket. Or the Romans. Or by the Church. Probably one of those two.

If the apostles only truly crucial function was to accurately record and preserve the exact facts and words of wisdom of Jesus, I would expect to see some reflection of that in the earliest writings of the church. What I find instead is a collection of letters in which the things Jesus said and did during his life don’t seem to have any importance whatsoever. I don’t see any indication in the epistles that Jesus was considered the most important earthly being the world had ever seen. Rather, it is only when he becomes a supernatural being and reveals himself supernaturally that he is significant.

And how do we know that they recorded the big historical events accurately? How could we possibly establish that the Sermon on the Mount was actually a single message rather than a compilation of various things Jesus was thought to have taught produced decades after his death. Everything we know about how the mind remembers things leaves very little room for confidence.

CARR: “. . . he just plain forgot what was written in the document he had in front of him and tried his best to reconstruct it (rather than just read it again).”

Scholars like Dunn imagine that Matthew had heard a different oral tradition that he liked better. Oddly, Matthew would copy Mark, often word for word, and then abruptly change to a preferred, different tradition that he liked better, rather than just write down the complete “better” tradition in his own words.

You can doubt everything if you want to. It’s a question of what’s more plausible, and it’s my sense of things that positing an historical Christian Rosenkreuz leaves us with fewer problems than the alternative.

My current thought is that some sort of minimal historical Jesus may have slightly more explanatory potential than not, but plausibility in the absence of sufficient evidence is still just speculation. Allison can be remarkably honest about the inherent limitations of the sources, but I still think that he is fooling himself if he thinks that he can know the gist of the real historical Jesus rather than just a theoretically possible historical Jesus.

A story was created in which the character of Jesus fulfills the law and Old Testament ”prophecies”.

The rest of the details, rather than staying loyal to a genuine tradition based on apostolic succession, emerged, changed and were reshaped in response to external influences (the destruction of Judaea in primis) and the needs of individual communities – including the very convenient idea that Jesus was ”historical”.

This is because in canonical Gospels there could be clues to so many controversies, disagreements and schisms in the early Christian communities: there was no ”Truth” for them to agree on – they were involved in the active production of a faith.

You can doubt everything if you want to. It’s a question of what’s more plausible, and it’s my sense of things that positing an historical Esther leaves us with fewer problems than the alternative.

It could be that positing a “historical Esther” based on The Book of Esther would leave us with “fewer problems” than an ahistorical one. But would it get us any closer to the truth? Because the truth matters more than convenience. It is the enormous cultural prestige of the Bible that blinds us from alternative explanations, not anything inherent to the texts themselves. The sanctity of the Bible must be protected, because Western culture has far too much emotionally invested in it being true on some level to allow honest and objective scrutiny.

The phrase, “a historical Jesus leaves us with fewer problems than a mythical one” pops up regularly like a mantra, but I have yet to see it accompanied by a list of what problems are solved more easily by that historical person. The entire historical Jesus quandary and uncertainties surrounding Christian origins are all generated by the problems tossed up by the historical Jesus model. Mythicism is generated by a recognition that the historical model hasn’t worked.

I was reading through Niels Peter Lemche’s The Old Testament: Between Theology and History today, and I found his discussion of the theological consequences of “the collapse of history” quite relevant to both my personal project and the so-called “mythicism” debate. The problem, I think, is the Bible occupies to distinct domains: theology and history. Unfortunately for the rest of us, the theology of the believers rests upon the historicity of Bible. Therefore, from that perspective, having an historical Jesus does indeed present fewer problems to the believer because his theology can remain intact.

I was originally thinking of William Dever as the person who best exemplifies this dynamic. He accuses so-called minimalists of being post-modernists and even “nihilists,” but the fact is that their history is manifestly modern in that it seeks to understand the objective truth behind the composition of the Old Testament. Far from running away from the meta-narrative, they are positing their own. That being said, Dever is correct in that the “minimalist” history of Israel reduces his theology to nothingness, but only because Dever does not have a mind as nimble as Thomas Brodie’s to reconcile his continued belief in the absence of the historicity of the Bible stories. Dever, like Allison, is more than willing to sacrifice his own integrity to protect the integrity of his belief system.

In my opinion one should never underestimate the human ability to compartmentalize. Evolution was no less threatening to the faithful and yet Christians still soldier on despite its overwhelming acceptance in academia. Just as easily as Genesis was contrived, this theological conflict was “resolved” in the minds of many a believer through the harmonization between doctrine and science in the comforting narrative that God engineered natural processes as a Rube Goldberg machine to achieve his ends. You don’t need an elaborate reconciliation between competing cognitions for the irrational mind to do what it does naturally. Heck, historicity poses just as much of a problem to theology by reducing the incredible miracle-working savior Jesus to the obscure peasant Jesus yet many Christians have no issue conflating the two and even appealing to the consensus to establish the resurrection as an historical fact by extension.

I tend to think that much of the dogmatism behind the historical model is grounded in the esteem of a cultural icon rather than the supposed desperation of a religious narrative.

TIM

you omitted a not-so-famous Yogi-ism.

A few years ago, Yogi’s wife, Carmen, asked him where he wanted to be buried.

“You were a star in the Bronx, but we’ve made our home here in New Jersey. And you grew up on The Hill [in St. Louis]. Where do you want us to bury you, Yogi?”

Yogi’s answer: “Surprise me.”

I like it. And as with most of the Yogi-isms I’ve heard, if it isn’t true, I don’t want to know.