The earlier posts, “Act 1” covered Brodie’s Part One of Beyond the Quest. That covered the period of Brodie’s intellectual discoveries from his late teen years till June 1972 (when he was about 30 years of age). Much of the setting was Trinidad. Brodie titled that Part of his book, his first four chapters, “The First Revolution: Historical Investigations” and explained its theme:

The earlier posts, “Act 1” covered Brodie’s Part One of Beyond the Quest. That covered the period of Brodie’s intellectual discoveries from his late teen years till June 1972 (when he was about 30 years of age). Much of the setting was Trinidad. Brodie titled that Part of his book, his first four chapters, “The First Revolution: Historical Investigations” and explained its theme:

Becoming aware that biblical narratives are not necessarily reliable accounts of history.

The posts covering this section:

- The Making of a Mythicist, Act 1, Scene 1 (Thomas Brodie’s Odyssey)

- Making of a Mythicist, Act 1, Scene 2

We now come to Part Two.

Part II

The Second Revolution: Literary Sources

Becoming aware of where biblical writers found much of their material

Chapter 5

The setting is Europe, Normandy. 1972. Brodie is studying for exams in Rome.

While in Trinidad he had taught the Gospel so Matthew knew it well. Now he was studying Deuteronomy when the abductive moment flashed:

Now I was focused on Deuteronomy when I suddenly said ‘That is like Matthew, that is so like Matthew’ — something about the sense of community, the discourses, the blessings and curses, the mountain setting. (p. 31)

Other similarities suggested themselves in the following days:

- aspects of the Elijah-Elisha narrative “showed startling similarities to Luke-Acts”

- the book of Wisdom’s confrontation between Wisdom and the kings of the earth was in some ways suggestive of the meeting between Jesus and Pilate in the Gospel of John

While in Jerusalem, at the École Biblique, a center of biblical historical and archaeological studies, Brodie continued his study of the Septuagint (Greek Old Testament) with Matthew in mind. Only flimsy and tenuous connections with Matthew could be noticed, however, until he reached Deuteronomy 15.

Since beginning this series I have discovered James McGrath’s distortion of Brodie’s book so where appropriate I should make clear what Brodie really says. McGrath speaks of Brodie’s “extreme parellelomania”. It is one thing to question and debate specific claims that certain passages were borrowed from others, but quite another to dismiss any such argument out of hand because we don’t like its implications. I emphasize the passages that clearly escaped McGrath’s notice.

Connections with Matthew seemed few and flimsy. Then suddenly, in Deuteronomy 15, the search came to life. The repeated emphasis on remission resonated with Matthew’s emphasis on forgiveness (Mt. 18). Both use similar Greek terminology. Obviously such similarity proved nothing. But further comparison revealed more links. And the Deuteronomic word for debt, daneion, is unknown elsewhere in the Bible — except in Matthew 18. Gradually the pieces of the puzzle began to fall into place. Matthew 18 had used first-century materials, including Mark, but it had also absorbed Deuteronomy 15. (p. 32)

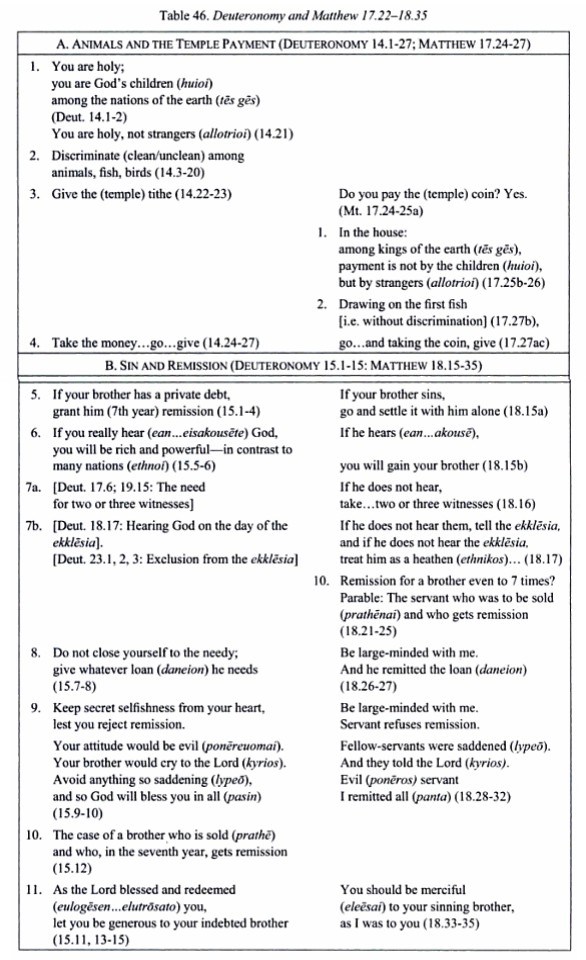

Here is a copy of Brodie’s table on this particular comparison from another work of his, The Birthing of the New Testament:

If you rely on that table alone you will be short-changing your understanding of Brodie’s analysis. That table forms a basis for an eight-page detailed analysis (link is to the Google book where those pages — 241 to 248 — can be read online).

If you rely on that table alone you will be short-changing your understanding of Brodie’s analysis. That table forms a basis for an eight-page detailed analysis (link is to the Google book where those pages — 241 to 248 — can be read online).

Obviously, Matthew does not reproduce Deuteronomy word-for-word. It was of the essence of the New Testament message that the existing scriptures needed reinterpretation, and so Deuteronomy is reinterpreted and synthesized. Even Mark’s gospel, despite all its newness and its New Testament character, had already been subjected to Matthew to a certain process of interpretation and synthesis. For instance, the episode . . . concerning the epileptic demoniac had been reduced by Matthew from sixteen verses to seven. . . If Mark often needed reinterpretation and synthesis, then all the more so did Deuteronomy.

Unlike Deuteronomy 14, Mt. 17.24-27 does not mention a variety of animals (clean and unclean) nor does it refer to the temple tithe. But it tells the incident of the temple tax and the fish. And unlike Deuteronomy 15, Matthew 18 is not directly concerned with granting remission (aphesis) to debtors and slaves. But it lays great emphasis on remitting or forgiving (aphiemi, 18.15, 21-22), and it illustrates forgiveness through a parable involving debtors and selling a debtor (into slavery; 18.23-25).

What emerges is that Matthew has modernized Deuteronomy 14-15, for instance by replacing the temple tithe with an incident involving the temple-tax. But he has also done something more fundamental: in accordance with a strategy which is found elsewhere in the ancient world and in the New Testament, he has internalized the older text. Where Deuteronomy was concerned with a remission which was primarily external, Matthew shifts the emphasis more clearly to the internal, to the remission which occurs within the heart.

The essence of this policy of internalization had already been indicated by Matthew in the Sermon on the Mount. . . . (p. 241)

Brodie sums up:

In the preceding array of similarities, there are indeed some which are obscure or questionable. . . .

But there is a whole series of similarities which in varying ways are striking or even unique:

- Position: both texts, taken in their totality, occur within the central discourse of their respective documents (within the second discourse in Deuteronomy, and within the third discourse of Matthew).

- Broad themes: Both texts deal with variations on the same ideas: temple payment and remission.

- Similarities of the subsections: Again and again, the basic elements of the Old Testament text may be found in adapted form in Matthew.

- Order: By and large, the order both of the themes and of the subsections is the same in both texts.

- Linguistic continuity: Several of the subsections share words or word-clusters which are (almost) without parallel in either testament.

Furthermore, the differences, great though they are, are not meaningless. Most of them can be accounted for through a few consistent practices: synthesis, modernization, and internalization, and through adaptation to the requirements of Matthew’s new narrative. Nor are these practices alien to what is otherwise known in Matthew. . . .

Therefore, it seems reasonable to conclude that Matthew engaged not only the broad outlines of Deuteronomy, as Frankemölle and Grassi [this link is to an English language abstract] indicated, but also the down-to-earth body of the text. He has synthesized part of Deuteronomy’s center and has adapted it for a new age. He has not written to destroy the law, but to fulfill it. (p. 248)

My own mixed responses

Excuse me while I interject here with my own responses to some of Brodie’s arguments. I sometimes find myself in a love-hate relationship with them. Some of his literary borrowings strike me as spot-on! But sometimes I have questions and want to take time to consider all the ins and outs before committing to the next step. Brodie’s deeper discussions do not come across to me as being for the impatient or lazy scholar or general reader. It takes time for me, at least, to consider fully his arguments and then to weigh and evaluate them. That’s why in the past I have skimmed his points, laid them aside, forgotten them, — only to return to them later and take a closer look — still not sure I lay them aside again, — until finally I settle down to think through point by point what he is arguing. Then I wonder.

Other readings in fact help me to appreciate some of Brodie’s points. Shwartley, Roth, Kee, Kelber and most recently Rikki Watts have made significant progress in helping us identify the idea behind the larger structure of the Gospel of Mark. Why is it structured the way it is, with Jesus

- crisscrossing the lake and wandering around Galilee and beyond, performing miracles, calling disciples and meeting religious challengers;

- followed by a middle “on the way” section in which he performs fewer miracles, teaches a lot about discipleship, speaks in riddles about his coming passion;

- and finally moving on from Jericho and into Jerusalem, being hailed as a king, cleansing the temple, debating authorities and finally being put on trial and executed as “king of the Jews”?

Is this structure based on historical reminiscence or is it a “re-writing”, embedding a “transvaluation” (for the benefit of a “new people of God”) of the history (Exodus – Sinai – Wilderness – Conquest – Temple – Kingdom) and prophecies (Isaiah’s New Exodus and Return) of Israel in the Old Testament?

If so, once we see Mark’s Gospel as a new history of a new people of God modeled upon the old, then I think it becomes a lot easier to accept some of Brodie’s detailed correlations as more plausible.

One thing is clear. Brodie’s arguments do NOT lend themselves to a facile “parallelomania”. They require study, thought, argument, rebuttal. By rebuttal I mean grappling with the detail. Testing them. Not mindlessly scoffing at them. They invite follow-up with the other scholarly works he cites for a broader context and appreciation (e.g. Frankemölle and Grassi). A lazy or incompetent scholar, or one inflicted with a “mythicist derangement syndrome”, would be left behind in such an exercise.

Brodie’s first feedback

The first response Brodie received to his Matthew-Deuteronomy link was “resoundingly negative” — it lacked, so the feedback said, both method and logic.

The solution?

Brodie was advised, no, he was “instructed” (he writes) by the same source to compare how Matthew worked with other Gospels and especially with Q.

But other scholars were not so negative in their assessments.

Langlamet, professor of Old Testament, said Matthew’s dependence on Deuteronomy made immediate sense to him (‘Some form of midrash’, he said). He had once thought of the idea, but had never developed it. Boismard, lecturing on John, simply asked, “Are you learning?’, and when I answered yes, he said ‘Then stay with it’.

And that’s what he did.

Soon the pattern of the Gospels’ literary dependence upon the Septuagint and on some of the epistles began to emerge.

We’ll look at that outline in the next post in this series.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Thanks for this series. I grew up being taught that God determined that Israelite history would prefigure and frame the coming internalized Gospel. The Reconstruction/Theonomy movement argued the same for me as I got older. It all made some sense to me but I always wondered why internalization had to evolve that way. Brodie and others have since offered a natural and better explanation for me.

Surely Brodie wasn’t the first person to notice Matthew’s literary dependence on Deuteronomy? If so, that alone would be a stunning indictment on the shoddy and naive methods of so-called scholars.

I think there are some very orthodox scholars who, being completely confident in their beliefs, see no problem in drawing out parallels between OT and NT stories. Here http://ntwrightpage.com/Wright_Paul_Arabia_Elijah.pdf for example N T Wright explains some of the implied biography of Paul (in the epistles) in terms of Elijah’s biography. Perhaps it is only those who feel threatened in their beliefs who must protest too much about paralellmania.