The Forgotten Stooge

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Can’t we all just get along?

In a recent post, Tom Verenna urged us all to stop using derogatory words to describe people whom we disagree with. He did that hipster thing where his sentence gets broken up into one-word, emphatic, staccato commands:

This. Has. Got. To. Stop.

That. Is. So. Cool.

Wait a second. What, exactly, has got to stop? Oh, here it is. This:

Someone disagrees with an argument made by someone else and they decide this person must be ‘incompetent’ because their argument is different.

If you’re at all familiar with the art and science of political speech and propaganda, you will recognize that sentence as a prime example of what we call “framing.” Before explaining Neil’s complaint against McGrath’s inadequate review, Tom needs to pre-explain or frame the argument.

Tom would have us believe that Neil’s gripe has nothing to do with Dr. McGrath’s longstanding pattern of over-the-top behavior whenever he gets the slightest whiff off Jesus mythicism. Not at all. It’s about “someone” not liking someone else’s “different” argument.

A different drummer

So what is McGrath’s “different” opinion? I’m glad you asked. Let’s list a few and then discuss.

- Mythists don’t follow “the rules of scholarly inquiry.”

- “Mythicist language is designed to make lies sound truthful.“

- Mythicism is just like creationism.

- Mythicism is just like “9/11 trutherism.”

- Mythicists are just like the people who think Sandy Hook was a conspiracy.

- Mythicists are just like birthers.

I could go on. You can find many more “scholarly observations” using fairly simple Google searches. For example, here’s how you can search for specific words, restricted to the Cakemix site:

site:www.patheos.com/blogs/exploringourmatrix "mythicist"

In case after case we see that McGrath disagreed with an argument made by someone else and decided that, because his or her argument is different, that person must have psychological reasons and ulterior motives for being “wrong.” McGrath feels compelled, no doubt as a public service, to explain the personal motivations for mythicist behavior. McGrathian conjecture knows no boundaries. Perhaps they have some pathological predisposition to believe in conspiracy theories, or they have an obsession with parallelomania. Perhaps they are insane.

McGrath, in his review of Thomas Brodie’s memoir, made a passing reference to “the bankruptcy of Jesus mythicism,” accusing Brodie of having “complete disregard for other possibilities.” Naturally, he doesn’t indict Brodie alone — all mythicists must be tarred with the same brush.

Exemptions for scholars

I bring all this up to illustrate the rules of engagement. McGrath can take broad swipes at every mythicist, even to the point of comparing them to denialists of all stripes — truthers, birthers, YEC-ers, you name it. And for Saint Thomas of Verenna, that’s just hunky-dory.

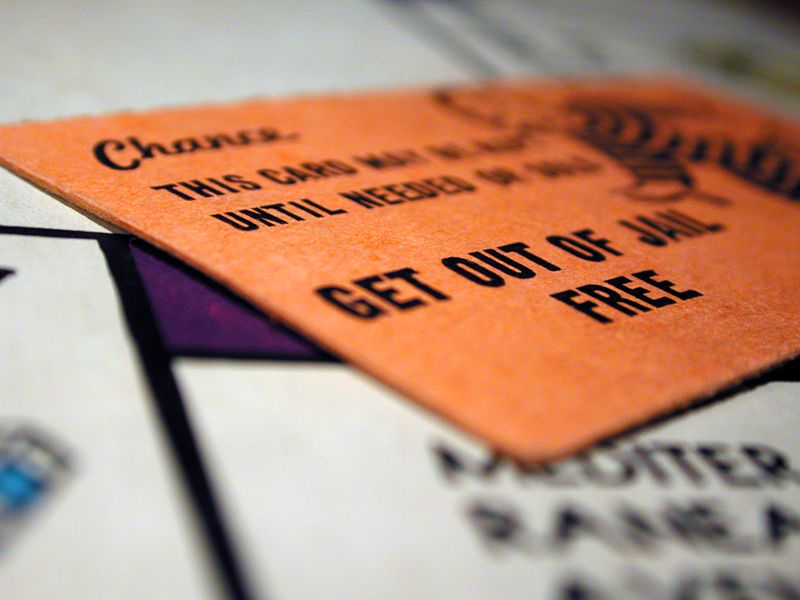

But if Neil says that McGrath’s inability to get the basic facts right points either to dishonesty or to incompetence, then he has crossed the line. One must always first extend the professional scholar the courtesy of an “out” — a get-out-of-jail free card. Namely:

As an academic, James has many responsibilities–responsibilities that an amateur like Mr. Godfrey cannot understand fully (as he does not have these same responsibilities–nor would he likely want them).

At this point, a less charitable observer — me, for example — might note for the record that the very busy, very professional McGrath has plenty of time to blog about Doctor Who, and when he does, he almost never gets the details wrong. No, it is always those posts that draw upon his core expertise (you know, his job as a New Testament scholar) or relate to his favorite bête noire (you know, mythicism) in which he makes glaring errors. But that would be uncharitable.

You might think because someone has come forth as a public intellectual, that he would be held to a higher, not lower, standard. That’s hopelessly naive. On the contrary, McGrath gets special dispensation. Didn’t you know that? And will Neil take these helpful hints in the magnanimous spirit with which they were offered? Probably not, laments St. Tom:

He will likely interpret this very post as some aggressive move against him, rather than the constructive criticism it is.

So there.

What is competence?

I do not broach the subject of scholarly incompetence lightly. While I may from time to time poke fun at the “anxiety of historicity” that pervades much of today’s NT scholarship, the vast majority of scholars are quite competent. They may have blind spots, but so do we all.

In fact, competency (the basic ability to do one’s job, or perform a basic skill, like “review a book”) is a sliding scale. You can be wrong about something and still be marginally competent. I’m reminded of a story I heard while I was an undergrad at the University of Maryland. A professor told us that one of his colleagues had recently taken a tour of historical sites around the Aegean Sea and parts of the Mediterranean. It was there that she first encountered the squat toilet.

Impressed, she began to write a short paper on this fascinating contraption. How wonderful and considerate it was, she opined, to find these lovely foot-washing devices after a long day of trudging through dry landscapes and dusty ruins. Fortunately, someone stopped her before she published it. Apparently, nobody on the trip stopped her from putting her feet in the toilet. All these years later I wonder if, supposing her paper had been published, she could have claimed it was all in fun.

That’s a pretty big blind-spot, and it does make you wonder about somebody’s competency when he or she doesn’t know such basic things. For example, awhile back we took McGrath to task for not understanding the basics of the Documentary Hypothesis. We’ve also poked fun at him for citing scholars who argue the exact opposite of what he claims they are. I could relate more examples of other basic errors, but the point is none of these mistakes alone proves incompetence. It is rather the pattern of error and, moreover, McGrath’s inability to admit he is wrong and refusal to learn from his mistakes that lead me to the conclusion that he is not competent.

A long time ago, I gave up on directly asking McGrath questions. He won’t answer. He will not engage you in an open, honest dialog. So I’ve stopped trying. I will, however, reserve the right to point out his continuing mistakes as well as his bad faith in dealing with mythicists.

Was Paul a tentmaker?

What sort of bad faith am I talking about? Well, here’s a prime example from McGrath’s scathing remarks about Brodie’s suggestion that Paul’s supposed profession may have something more to do with theology than with history.

His treatment of the case of Paul, like Brodie’s work on Jesus, illustrates both the usefulness of detecting literary parallels, echoes, and borrowings, and the bizarre results of taking that approach to the extreme that Brodie does, into the realm of unchecked paralellomania [sic]. His argument that mundane details about Paul were fabricated on the basis of earlier literature includes the claim that the reference to Paul having been a tentmaker was inspired by references to tents in the Jewish Scriptures, including God spreading out the heavens like a tent (p.151). Using such an approach, being willing to claim even identical prepositions as evidence of literary dependence, is a method which could claim that absolutely anything is derived from absolutely anything else. The sad thing is that the bizarre extremes to which Brodie is willing to go to make one text wholly derivative from another cheapens and detracts from the legitimate points he makes about the smaller number of texts and points of contact that have strong evidence in their favor. (emphasis mine)

That’s quite an accusation. Does Brodie really claim that some writings are based on others because of “identical prepositions”? Perhaps so, but McGrath doesn’t give us any specifics. Naturally, he doesn’t have to provide specifics, because busy scholars get a free pass.

Note the scare words in that paragraph. Brodie’s ideas are “bizarre” and “extreme.” Brodie, McGrath is telling us, has failed to show restraint. How do we know he’s gone too far? Because he’s reached the wrong conclusions. You see, sophisticated NT scholars know how the game is played. A writer needs to find that Goldilocks Zone, where the Jesus porridge is ju-u-u-ust right. Anyone out on the “fringes” can be ignored (and insulted), because they either accept too much material as authentic or because they accept too little.

So, to McGrath’s specific point on Paul as a tentmaker: Is this an outlandish idea? Well, let’s examine all of Brodie’s reasons, and not just the ones McGrath scoffed at. First of all, Brodie admits that the reference in Acts 13:3 sounds legitimate. However, he says that before we take it at face value, “it is necessary first to investigate the literary relationship of tent-making to the Septuagint image of the tent and to the image of Paul as an architect (1 Cor. 3:10-11).”

- The term in 1 Corinthians is quite specific: σοφὸς ἀρχιτέκτων (sophos architektōn) or “wise master builder or architect.” Cf. to the Jewish tradition of calling wise Rabbis, doctors of the law, and their followers “builders of the law.”

- “In Isaiah, God spreads out the earth as a tent.”

- “[T]ents are given a central role among people of the desert.”

- In John’s gospel, we’re told that the Word sojourned or “tented among us.” (John 1.14) In Greek: ἐσκήνωσεν ἐν ἡμῖν (eskēnōsen en hēmin).

He could also have mentioned the importance of the tabernacle (portable tent shrine) in the OT as the precursor to the Temple in Jerusalem. YHWH dwelt or “tented” with his people wherever they might roam. He might also have discussed the importance of the tabernacle in the Epistle to the Hebrews.

Stop answering our rhetorical questions!

But the main point to understand is this: The New Testament is replete with examples of additions, deletions, and alterations that have their roots not in tradition, but in authorial invention. Brodie’s sin is answering that rhetorical question: “Why would anybody make it up?” Brodie says, “Here’s why, and here’s how.” And that drives people like McGrath round the bend.

We should mention that occupations in the New Testament and in later Christian tradition often have theological meanings. We have fishermen who become “fishers of men.” We have Mary, who was supposed to have been a weaver (or a spinner of wool) — and who created the very temple veil that split down the middle during the crucifixion. Some people still believe this story is true.

Jesus picked up his hammer and saw . . .

Finally, we have a muddied reference to Jesus as a laborer or carpenter. On this last point, Geza Vermes had this to say in Jesus the Jew: A Historian’s Reading of the Gospels:

Was he a carpenter himself, or was he only the son of a carpenter? The confused state of the Greek text of the Gospels usually indicates either a) a doctrinal difficulty thought by some to demand rewording; or b) the existence of a linguistic problem in the expression in Hellenistic terms of something typically Jewish. Here the second alternative applies The congregation in the synagogue voices astonishment.

‘Where does he get it from?’ ‘What wisdom is this … ?’ ‘Is not this the carpenter/the son of the carpenter … ?’

Now those familiar with the language spoken by Jesus are acquainted with a metaphorical use of ‘carpenter’ and ‘carpenter’s son’ in ancient Jewish writings. In Talmudic sayings the Aramaic noun denoting carpenter or craftsman (naggar) stands for a ‘scholar’ or ‘learned man’.

This is something that no carpenter, son of carpenters, can explain.

There is no carpenter, nor a carpenter’s son, to explain it.

Thus, although no one can be absolutely sure that the sayings cited in the Talmud were current already in first-century AD Galilee, proverbs such as these are likely to be age-old. If so, it is possible that the charming picture of ‘Jesus the carpenter’ may have to be buried and forgotten. (p. 23, emphasis mine)

Was Vermes a parallelomaniac using unsound methods to reach “bizarre extremes”? Brodie, after all, said that Paul’s identification as a tentmaker could have literary, metaphorical meanings that later became historicized. Certainly, then, Geza Vermes is to be pitied, because the cited text above “cheapens and detracts from the legitimate points he makes” in his other, more palatable writings. Right?

I’m joking, of course. Geza Vermes believed in the historical Jesus, so he’s allowed to posit the notion that the carpenter myth “may have to be buried and forgotten.” In fact when Vermes died earlier this year, McGrath called him a “renowned scholar of ancient Judaism and the historical Jesus.” No pity. No scorn. McGrath had only nice things to say about the great scholar.

Tommy can you hear me?

But none of that makes any difference to Verenna. Fractured facts? Bad logic? Inconsistencies? So what? He’s too upset to bother with such trivialities.

He concludes with this lachrymose plea:

So maybe we can start treating each other with a little more respect here? Maybe we can do away with all the polemical name calling? It is intolerable and I find that I have a hard time reading through all the vitriol to find the point that is being made.

Cry. Me. A. River.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Very well put – I often find the hand-wringing in discussions about the origins of the figure of Jesus over credentials and methodology seems to hinge on the conclusions one reaches; the ‘historicists’ are happy to accept any argument from anyone who comes to the correct interpretation but will turn on and denounce anyone no matter how lauded in the past for their expertise if the deviate from the dogmatic assertion of the traditional story.

As a sort of appendix to this post, let me paste here a friendly little back-and-forth between Steven Carr and Tom Verenna.

Ah, the sweet smell of civility and respect.

Mr. Carr is a bit of a gadfly, but he’s also keen-eyed and usually right. No wonder he gets on people’s nerves. 🙂

“Brodie’s sin is answering that rhetorical question: “Why would anybody make it up?” Brodie says, “Here’s why, and here’s how.” And that drives people like McGrath round the bend.”

Indeed, one could say that New Testament criticism’s primary focus is devise schemes to prevent people from seeing what it plainly is, i.e., narrative theology based solely on literary sources. No oral history at all.

I knew something was up with Brodie when he included (in “The Birthing of the NT”) the possibility that the entire historical picture of Paul was fraudulent, based on the close literary dependence of sections of the epistles to sections in the LXX. Your typically brain-washed NT scholar would *never* have even thought of that, much less come right out in print with it. It isn’t a thinkable thought within NT studies.

Keep up the Brodie posts. He deserves to be championed.

Everything you say is true – but it is also true that using an emotionally charged word like “INCOMPETENT” is just going to keep the flames stoked. After all, a professional scholar’s only stock in trade is his competence, and without that, he might have to get a job at McDonald’s.

That’s why I prefer the term “Mythicist Derangement Syndrome” (based on the American political competing charges of Clinton Derangement Syndrome of Bush Derangement Syndrome – just google those terms.) It allows for a general competence on all issues other than the particular one that sets off the derangement. It is a form of temporary insanity that has the possibility of a cure.

The question I posed on Tom’s post was whether a person can be a “competent” phrenologist. I could imagine a rigorous course of study and internship, but that wouldn’t change the fact that those little bumps simply don’t contain the information that the phrenologists are trying to get from them. As the methodology is hopelessly flawed, I think that the best one could hope for is to be a “proficient phrenologist.

I think the problem with historical Jesus studies is analogous; the information is simply not there. I am open to the possibility that someone can make a persuasive case for the likely existence of some sort of minimal historical Jesus, but I do not think that our sources contain any credible information about his life or ministry. The reason that scholars can come up with “absolutely anything” is because our sources are inherently (and I suspect irretrievably) problematic. What McGrath doesn’t see is that his historical Jesus is just one of those anythings.

What really struck me was this knee-slapper:

“And if one were to simply direct James to the information responsibly–you know, like civil human beings will do–then James can then correct or amend his claims based upon information he may have missed.”

Of course. And this is from a person who will not allow me to post on his blog any corrections or notices of oversights to any critical posts he writes about me.

Not to mention his blatant admission that he never read Salm’s book on Nazareth when he attacked it, and even said he didn’t have to read it to review it!

And this is the person who suddenly tried to make up and treat me like a buddy when I began to review his book, ‘Is This Not the Carpenter?’

Exactly. He’s living on another planet. It’s like we’re in a Kafka novel and characters like St Thomas are trying to completely screw our minds into disbelieving all we are experiencing.

Hello,

I am new here. I do not know who Tim Widowfield is. I tried to look him up through google, and I indeed found articles by him, yet I did not find a page about him, personal page, wikipedia page, nor any.

Can anyone explain to me who Tim Widowfield is?

Thank you in advance.

He’s a male biped, about 5’11”. You can read more about him here — http://vridar.org/about/

Thank you very much.