This continues the previous post on Jesus: An Historian’s Review of the Gospels by Michael Grant. Why two posts on this? Since some New Testament scholars point to Michael Grant as evidence that academics outside biblical studies employ the same methods and reach the same conclusions about the historicity of Jesus as they do, won’t hurt to address his work in some detail.

This continues the previous post on Jesus: An Historian’s Review of the Gospels by Michael Grant. Why two posts on this? Since some New Testament scholars point to Michael Grant as evidence that academics outside biblical studies employ the same methods and reach the same conclusions about the historicity of Jesus as they do, won’t hurt to address his work in some detail.

For Michael Grant, Jesus was better and greater than any other person in the history of the world. If the Gospels say he did or said something that reminds us of what other persons have said or done, Grant is always quick to expostulate that Jesus said or did it with such greater force or power that he made it sound or look unprecedented. Usually he just makes this declamation of Jesus’ superiority as if it must be a self-evident truth. At the same time he generally informs readers exactly what was in the mind and feelings of Jesus, too. Recall from my earlier post:

He felt an immovable certainty that he was the figure through whom God’s purposes were to be fulfilled. This absolute conviction of an entirely peculiar relationship with God was not unknown among Jewish religious leaders, but in Jesus it became a great deal more vigorous and violent than theirs. (Jesus, p. 77)

and

Jesus’ extreme obsessional conviction of a unique relationship with God makes any attempt to fit him into the social, institutional pattern of his time, or into its habitual concepts of thought, a dubious and daunting proposition. (Jesus, p. 78)

When in the Gospel of Luke we read of Jesus making an observation well known from rabbinical literature, that a poor woman giving her few pennies was making a greater sacrifice than any of the rich donors, Grant explains:

This story is exactly paralleled in rabbinical literature. And yet Jesus applied it more aggressively, for according to Luke, he accompanied his utterance by an attack on the Jewish scribes or doctors of the Law who ‘eat up the property of widows.’ Jesus carried his championship of the underdog beyond the bounds set by other Jews of the age. (p. 57)

Even the most banal teachings attributed to Jesus are said to be given a sharpened edge by Jesus:

Nor were Jesus’ ethical precepts for the most part original or novel, since ninety per cent of them were based upon injunctions that had already been offered by other Jewish teachers.

However, Jesus sharpened certain of these themes. (p. 25)

This is all Grant’s own imaginative fantasies being projected into the literary Jesus, of course. Gospel sayings of Jesus are quite trite so Grant attempts to rescue them by saying Jesus said or felt them “more vigorously”, “more powerfully” or “more sharply” than anyone else.

By now I think some readers will begin to understand why Grant’s biographies of ancient persons are generally for popular, more than scholarly or graduate student, consumption.

.

A New Testament scholar’s evaluation of Michael Grant’s “historical Jesus”

Barry W. Henaut, author of Oral Tradition and the Gospels: The Problem of Mark 4, introduces his study with a quotation from Michael Grant’s Jesus, an historian’s review of the Gospels:

Barry W. Henaut, author of Oral Tradition and the Gospels: The Problem of Mark 4, introduces his study with a quotation from Michael Grant’s Jesus, an historian’s review of the Gospels:

[A]mong the host of Commandments Jesus singled out two as supreme, Love of God and of our neighbour. This pairing of the two ordinances in absolute priority over all other injunctions occurs elsewhere in Jewish thought after the [Hebrew Bible] and may not, therefore, be Jesus’ original invention. But the stress he laid on it was unprecedentedly vivid.

Henaut comments:

What could be more Christ-like than the Golden Rule? The forcefulness of this aphorism, particularly in the Sermon on the Mount, for many captures the essence of Jesus. Michael Grant seems to be engaged, not so much in the historian’s craft, but rather in stating the obvious.

But times change. A dozen years later the Jesus Seminar would overwhelmingly deem the Golden Rule an inauthentic saying.

In light of the extensive literary parallels from Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Zoroastrianism and Judaism there is no way of knowing whether Jesus ever uttered this aphorism. The early Christian community had access to a variety of sources for this sentiment and may have ascribed it to Jesus at any time prior to the Gospels. What initially looked self-evident now becomes a victim of what Van A. Harvey calls the morality of historical knowledge. Grant’s presentation has become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The vivid presentation of Jesus in the Gospel narrative, which Grant recognizes to be a secondary composition, nevertheless has formed the basis of his reconstruction.

Grant has filtered the Gospels through the hermeneutics of C.H. Dodd and J. Jeremias, a method that is now outdated. (p. 13, my bolding)

So it appears that at least one New Testament scholar recognizes exactly what Michael Grant is doing and it is not doing history in the same way classicists or other historians do history with their documents. He is doing outdated New Testament hermeneutics.

.

How Michael Grant does “history” on Jesus

So how does Michael Grant approach the study of Jesus? Are his normal approaches to historical investigation up to the task? Sadly, he says, “No, they are not.” He needs something far more sophisticated! He turns to an Anglican missionary and bishop, Stephen Neill, for the answers:

The extraction from the Gospels of evidence about the life of Jesus is a singularly difficult process. Students of the New Testament, it has been suggested, would be well advised to study other, pagan fields of ancient history first — because they are easier! For the study of the highly idiosyncratic Gospels requires that all the normal techniques of the historian should be supplemented by a mass of other disciplines though this is a counsel of perfection which few students, if any, begin to meet. (Jesus, p. 197)

Impressive! And Michael Grant is not making this up. He is referring to the words of Bishop Stephen Neill who wrote (among other prominent works) The Interpretation of the New Testament, 1861-1961. (That work has since been updated by another Anglican bishop, N.T. Wright. A search to learn more of Bishop Neill unhappily ends with the discovery of a brilliant but sadistic soul who left a secret trail of tormented victims throughout his career. His Wikipedia page waits for an update. I am unable to read Neill’s book for myself since it is only available online to American citizens.)

Michael Grant claims to be writing “as an historian”, but he looks to the theologians to see how they should approach the Gospels as a special case. Indeed, Grant liberally splashes his pages with citations pointing to New Testament scholars such as G. Bornkamm, C.H. Dodd, R.H. Fuller, J. Jeremias, D.E. Nineham, Geza Vermes and Stephen Neill.

But let’s backtrack a moment to catch up with one of those moments where Grant appears to turn his back on any notion that the arcane arts of theologians are required to extract reliable information from the Gospels.

.

Comparing elephants and disciples

The closest Grant comes to addressing normal historical methods is when he writes:

Certainly, there are all those discrepancies between one Gospel and another. But we do not deny that an event every took place just because pagan historians such as, for example, Livy and Polybius, happen to have described it in differing terms. That there was a growth of legend around Jesus cannot be denied, and it arose very quickly. But there had also been a rapid growth of legend round pagan figures like Alexander the Great; and yet nobody regards him as wholly mythical and fictitious. (Jesus, p. 200)

I wonder how many of Grant’s peers cringed when they heard that he was comparing the Gospels with the Histories of Livy and Polybius. Of course no-one disputes events if Livy and Polybius describe them differently. Firstly, look at the different ways Livy and Polybius describe Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps. The facts are not in dispute. One does not say Hannibal crossed the Alps after he invaded Italy and another before; one does not say he crossed with his army while another says the army crossed without him. These would be the sorts of differences we would expect if Livy’s and Polybius’s accounts are comparable to what we find in the Gospels. Rather, most of the differences are perceptions of the character of Hannibal: the patriotic Livy hates him while Polybius, a Greek historian, is more neutral. Yes, the Gospels also contain different attitudes towards the disciples, towards Jews and Romans. But they also contain much more significant contradictions that really do undermine their credibility as accounts ultimately derived from singular noteworthy events.

It is important to register that significant Gospel contradictions are cogently accounted for by entirely different narrative logic and theological interest of each author. In the Gospel of Mark, for example, Jesus calls his disciples at the commencement of his ministry, but in the Gospel of Luke Jesus commissions them only after he is well into his ministry, performing miracles and attracting large crowds. In Luke the disciples from the beginning are commissioned to be authoritative participants in the labours of Jesus. There are clear theological reasons for the difference and the narrative structures are completely different in order to convey these variant theological messages. (See Reasons for Luke to change Mark’s account of the calling of the disciples for more details. Of course there are many other examples of Gospel contradictions, some far more well known than this particular illustration.)

So the authors of the Gospels clearly do not consider their compositions to be historical records of events that really happened or that they are writing “history”, but they evidently understand that they are writing “parables” (Crossan’s term) that can be changed to convey different theological messages.

But that doesn’t mean that Jesus didn’t really call disciples at some time, does it? That is the rhetorical question that usually is thrown up in defence of the view that the Gospels are ultimately derived from genuine or distorted historical tradition of some kind. It is a meaningless point. Just because the stories told about John Henry and Paul Bunyan could have happened doesn’t mean they therefore did happen. Criteria other than “could have happened” are required. Michael Grant is embarrassing his profession for this gaffe. We will see why as we proceed.

We know who Polybius and Livy were, when they were born, where they lived, whom they knew and met, their political and social status, where they traveled, and why they wrote their respective histories of Rome. That is, we understand their interests and reasons for writing, and their interest and ability in writing a generally factual history. Their works find independent support in other sources. Contrast the Gospels: We have no idea who wrote them, when, for whom or why. Scholars speculate with informed guesses but can do no more. The Gospels of Mark and John do not even read like genuine history or biography. Their story flow and messages convey more mysteries than answers. They read like cryptic theological parables intended for select audiences “in the know”. It has recently been suggested, on the strength of seriously applied literary genre theory, that Mark is, indeed, a form of Jewish novel.

For all of these reasons (each one could be elaborated into a full post) it is nonsense to suggest that the Gospels should be read by historians in the same way they read Polybius and Livy.

Grant does sound very much like a theologian when he writes that historians attempt to determine what can be believed in ancient writings

on the basis of historical deductions and arguments which attain nothing better than probability [and] the usual standards of historical persuasiveness. (Jesus, p. 201)

What Grant is overlooking when he writes this is his many years of familiarity that comes from working with ancient sources. He has forgotten or has ceased to be consciously aware of what makes much found in the works of Polybius and Livy persuasive: our knowledge of the authors of those works and their reasons and intents in writing, the genre of their writings and the functions they served; the extra-textual confirmations of the general reliability of their works. It is all of that knowledge — too easily lapsing through familiarity into a subconscious recess of one’s mind — that justifies judgements of “probability” and “persuasiveness” in the case of classical sources.

.

Post-Freudian historian-theologian

Didn’t Albert Schweitzer say that reconstructions of the historical Jesus up to his own day had all been, in effect, reconstructions in the respective images of their Dr Frankensteins? Will Grant’s Jesus be more like Grant than the “real Jesus”?

Grant acknowledges Schweitzer’s point as he found expressed by Gunther Bornkamm saying that of all the tens of thousands of books written about Jesus “all” had failed insofar as they “all superimposed” or unconsciously projected their own modern viewpoints into the past.

So how does one explain this track record of failure if the methods of historical Jesus are so much more advanced and complex than anything found in more banal historical studies? Grant might have said that some of the tools used by scholars were developed after Schweitzer, but in fact the primary tool Grant himself relies upon, the criterion of embarrassment, was widely used among scholars well-known to Schweitzer.

The solution, Michael Grant implies, is that since Schweitzer there is little excuse for any scholar falling into that projection trap. The reason? Sigmund Freud! Scholars since Freud, he says, can do much better. Armed with the knowledge of how the devilish subconscious works, historians can henceforth be on their guard against anachronistically injecting their own world-views into the past:

The solution, Michael Grant implies, is that since Schweitzer there is little excuse for any scholar falling into that projection trap. The reason? Sigmund Freud! Scholars since Freud, he says, can do much better. Armed with the knowledge of how the devilish subconscious works, historians can henceforth be on their guard against anachronistically injecting their own world-views into the past:

[L]et us at least, in this post-Freudian epoch, be on our guard against introducing unconscious modernizations, so that we can then get on with our task of discovering and isolating the specific , and often to ourselves alien, features peculiar to the first, and not the twentieth, century AD. (p. 198)

.

Raptured by the optimism of the Second Quest

Simultaneously Grant acknowledges that the biblical scholars in his own generation who are studying the historical Jesus have learned to be more hopeful than Schweitzer was in surveying the scholarship up to his own time.

The task has often been declared impossible on the grounds that our information is too little and too late, and can do no more than create the picture of a picture, and can yield only a whisper of Jesus’ voice. But nowadays more and more scholars appreciate that this conclusion is unduly pessimistic. T. W. Manson, for example, has declared: ‘I am increasingly convinced that in the Gospels we have the materials — reliable materials — for an outline account of the ministry as a whole.’ J. Knox, too, believed us to be ‘left with a very substantial residuum of historically trustworthy facts about Jesus, his teaching and his life.’ And now Geza Vermes expresses ‘guarded optimism concerning a possible discovery of the genuine features of Jesus’.

And Michael Grant presents his book on Jesus as a legitimate contribution to the new quest for the historical Jesus:

Note that Vermes speaks of a possible future discovery. For, in spite of all this vast literature, the historical reconstruction of the life and history of Jesus has as yet hardly begun. Those were the words of Stephen Neill, published in 1962, and the passage of a few more years has not impaired their accuracy. So the further attempt that has been made in the present book is surely in itself not unjustified. . . . (Jesus, p. 198)

Is this because they had learned to apply the methods used by other types of historians? Not at all. Grant does not explain why this renewed optimism. But New Testament scholars know the reason. . . .

In 1954, after Albert Schweitzer had effectively dashed hopes of recovering the historical Jesus, Ernst Käsemann revitalized hopes of uncovering “the real Jesus” with his publication of “The Problem of the Historical Jesus”. This ignited what is known as the “New Quest” for the historical Jesus. Käsemann introduced the sorts of tools that were to make historical Jesus studies such a complex task quite unlike the comparative simplicity of the historical studies that Grant was used to. These tools were the application of form criticism to peel away layers of history behind the Gospel texts, and the criterion of double dissimilarity. Double dissimilarity means that we can only be certain about those words of Jesus that are unlike anything found in Judaism or early Christianity.

That a little professor named Dodd

Should spell, if you please,

His name with three D’s

When one is sufficient for God.

Grant is heavily (I would even say exclusively) indebted to New Testament scholars for his views about Jesus. He opens his life of Jesus with theologian C.H. Dodd’s popular view that Jesus taught a “realized eschatology” — a message that the Kingdom of God was already here on earth in the life and work of Jesus — as that view was modified by another theologian, G.E. Ladd. Ladd argued that Jesus taught both a “here and now” and a futuristic eschatology.

Jesus, then, fully and urgently participated in the current Jewish belief that the end of the world as we know it — the coming of the Kingdom of God — was imminent. But what was much more original, indeed the most original of all his beliefs, was the combination of this idea with the further conviction that the Kingdom had already begun to arrive . . .

It was true that the Jewish doctrine of the imminent Kingdom of God had long alternated with a belief that the Kingdom was in another sense eternal and that all which needed to happen in the future was for it to be realized, brought into effectiveness, upon earth. But that is not at all how Jesus put the matter. In striking, disconcerting contradiction (or so it seems at first sight) with his assurance of the imminence of the Kingdom, he also stated quite categorically on other occasions that it was already here. ‘If it is by the Spirit of God that I drive out the devils, then be sure the Kingdom of God has already come upon you’ . . . . This is a statement so alien to the thought of his time that once again it must be attributed to Jesus himself rather than to the Gospel writers or their sources [Grant here cites both Ladd and Dodd]. . . . This is not just the traditional Jewish statement that the Kingdom of God is always present. It is a far more remarkable assertion that salvation is beginning to be present here and now because Jesus himself has brought it in. (Jesus, pp. 20-21, italics original, bolding mine)

Grant is entirely indebted to the scholarship of theologians — and their arguments based on dissimilarity and other criteria — for his portrait of Jesus.

Here is one more instance. Grant draws upon the 1963 publication, Historicity and the Gospels, by theologian H.E.W. Turner, as his source for the following argument from dissimilarity (if not double dissimilarity) for another historical nugget about the historical Jesus:

A strong reason for regarding [Jesus’ parables] as basically genuine is the decline, indeed the disappearance, of this mode of teaching in the early Christian Church: parables would not, therefore, have been included by its members, the evangelists, unless Jesus had actually uttered them. (Jesus, p. 91)

Let’s look at some other instances where Grant draws upon other criteria found in the treasure-chest of theologians to flesh out his Jesus. One of Grant’s favorites is the criterion of embarrassment. The arguments will be very familiar to anyone who has any acquaintance with what New Testament scholars say about the historical Jesus. I am prepared to wager that one will find little comparable argument in his biographies of Julius Caesar or Nero. I sat through many classes studying Julio-Claudian emperors from the Roman sources in translation and I don’t recall once anyone suggesting that a detail must be true because the historian was conflicted between what was expected from him and what he really did not want to write, because of sheer embarrassment, if he could have avoided doing so.

.

Embarrassed Christians and their embarrassing historical riches

It would not be wrong to say that Michael Grant is presenting a layman’s synopsis of what a few theologians have written about Jesus. Anything he does in addition to that is far from scholarly. Although Grant sometimes reminds readers he is writing as “an historian”, he at no point informs readers what his methods of historical inquiry actually are. All of his justifications for any claim about Jesus come straight from the texts of religion and religious scholars.

Just a few of many instances:

When the evangelists attribute the same view [of the end of the world] to Jesus we must believe them since they would not have included a forecast which remained unfulfilled unless it had formed part of an authentic, ineradicable tradition. (Jesus, p. 19)

The embarrassment caused by this dilemma [Jesus being baptized for forgiveness of sins] is enough to refute modern denials that the Baptist ever baptized Jesus at all. For, once again, the evangelists would have been only too glad to omit this perplexing event; but they could not. 24 [The endnote is to: 24, R. H. Fuller, The Mission and Achievement of Jesus (SCM, 1954), p. 52.] (Jesus, p. 49 — Grant has forgotten he has no idea who the authors were yet he follows theologians’ precise reconstructions of their motives and interests!)

As every Gospel agrees, Jesus’ female followers remained conspicuously faithful to him right up to and after his death . . . . Since this superiority of the women’s behaviour was so embarrassing to the Church that its writers would have omitted it had it not been irremovable, there is every reason to regard it as authentic . . . ‘ In Jesus’ attitude toward women,’ C. G. Montefiore rightly remarked, ‘we have a highly original and significant feature of his life and teaching.’ (Jesus, p. 85.)

Jesus’ own family were among those who rejected him. . . .

Jesus’ desertion by his family, so contradictory to the pious birth-legends in Matthew and Luke, must have been one of the saddest events of his life, and he struck back with characteristic force:

If anyone comes to me and does not hate his father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters . . . (he) cannot be a disciple of mine.

This, once again, was an outrageous saying ensconced in the genuine tradition; indeed, so immovable that Luke not only preserved it but repeated it, making Jesus declare that such abandonments would not lack due rewards in the Kingdom of God. (Jesus, pp. 126-127 — of course Michael Grant, as much as the theologians he is following here, overlooks that family rejection is a standard motif that applies to those called by God as a matter of course.)

[Jesus’ Cleansing of the Temple] is so disconcerting, in its suggestion of violence, that it cannot be dismissed as a false concoction by the evangelists. Indeed, Matthew and Mark, at least, as their severe abbreviations of the story indicate, must have found it uncomfortably discordant with Jesus’ pacific reputation. Yet they could not leave it out because it was so firmly lodged in the record. (Jesus, p. 149 — again Michael Grant overlooks the very convenient plot function of this incident, not to mention its nature of a prophetic fulfillment, that offer strong reasons for thinking it to be a literary fabrication, as Burton Mack and Paula Fredriksen well recognized.)

The story of Judas must in its main lines be genuine, because it was too shameful for the evangelists to have invented. (Jesus, p. 155)

Then follows the horrible conclusion of the story, the Crucifixion. This, again, must be true because no one would have invented such a degraded end, a fatal objection to Jesus’ Messiahship in Jewish eyes. (Jesus, p. 166)

The fallacy of this criterion of embarrassment has been pointed out many times recently. Embarrassment is a factor to consider when assessing a writer’s interpretation of events, but it is only in biblical studies, as far as I am aware, that it is used to justify the wholesale certainty that an entire event itself did indeed happen.

.

“Let the scriptures be fulfilled”

A few rationalist sceptics might regard with some suspicion any story about Jesus that is said to be a fulfillment of an Old Testament prophecy. I am quite sure Michael Grant would have given scant credence to any suggestion that Alexander the Great might have decided to conquer his world in order to fulfill the Delphic or Theban oracles, or that Julius Caesar left the security of his home on the Ides of March in order to give some credibility to a seer. But Jesus is different. Grant does insist that very much of what Jesus said and did was said or done explicitly to fulfill a prophecy! How does he know? He says the Jews of his day were always looking for ways to see how history was going to be fulfilled or acted out anew in their own day. (He does not offer evidence for this assertion, but let’s continue. If nothing else, Grant does write a good story.)

We see here Michael Grant the theologian most consummately at work. If in the above sections of this post we saw how he followed the lead of theologians in ascribing anything attributed to Jesus as genuine if it were UNlike anything Jewish, here we find him attributing to Jesus anything that is so utterly LIKE the Judaism of his day as necessarily genuine. Jesus did indeed, says Grant, consciously seek to live a life that could be said to “fulfill the scriptures”:

Thus the entire course of history, it appeared to the Jews, was specifically directed by God in such a way that subsequent events would correspond to those earlier ones — which had, indeed, according to this view, been expressly designed to anticipate what was to happen later. . . .

Now this Jewish attitude was fully, consistently and perseveringly maintained by the early Christians, whose New Testament deliberately presented the career of Jesus as a mass of detailed fulfilments of what the Torah, the prophets and Psalms had foretold. . . .

As historians, however, we have to consider typology an essential factor because it often guided the course of events. To the followers of Jesus the entire Old Testament seemed replete with prophecies . . . about Jesus . . . . And it was a view that he himself shared. . . .

[D]oes this mean that he had deliberately arranged to act so that his action should fulfil the text in question? Or must one instead conclude that the happening has been subsequently invented . . . .

[I]n his earthly career, too, Jesus was said to have emphasized the same connection incessantly. ‘Let the scriptures be fulfilled,’ was his alleged declaration when he was arrested, according to Mark. . . .

Once again, there is every reason to agree that this correlation of Jesus’ experiences with the ancient scriptures does, indeed, go back to himself. As [conservative theologian] J. W. Wenham points out,

He uses persons in the Old Testament as types of himself (David, Solomon, Elijah, Elisha, Isaiah, Jonah), or of John the Baptist (Elijah); he refers to Old Testament institutions as types of himself and his work . . . . (Jesus, pp. 12-14)

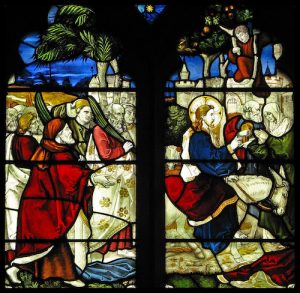

So when Jesus was said to be fulfilling the prophecy of Zechariah that Judah’s king would arrive riding on a donkey, Grant says that this was not a fabrication of an evangelist, but a deliberate historical act by Jesus who was consciously acting out the Zechariah prophecy:

Thus by acting out this passage of Zechariah . . . Jesus was able to stress that any such belief in his earthly, victorious Messiahship was misguided. His mission was of quite another kind.(Jesus, p. 144)

True, the story [of the Cleansing of the Temple] is in close conformity with Old Testament prophecies — which in the case of other Gospel narratives sometimes suggests that the evangelists have had recourse to fiction. . . . But the existence and demonstration of biblical predictions and prefigurations does not prove that the Gospels are inventing the story. On the contrary, it appears, as in his entry to Jerusalem, that Jesus deliberately modelled his actions on these scriptural foreshadowings. (Jesus, p. 149)

And so forth. According to Grant and many theologians, Jesus consciously chose to act out in his life what he expected others would recognize as Old Testament prophecies of his life.

.

Miracles? He must have done something!

So how does the historian explain the accounts of Jesus performing miracles?

Grant says that “Jesus must have done something” so it is quite within our rights to find rational explanations for the miracles. Except, that is, for the nature miracles such as walking on water. Nothing like those miracles ever really happened.

What, in fact, did Jesus do? We cannot say for certain. But we can . . . rationalize. Rationalization, the foisting of materialistic interpretations upon the miracles, is a familiar process which has been with us for hundreds of years. It is not always very profitable. But in this case it is legitimate because Jesus must have done something. Possibly he made a distribution of a few loaves and explained its symbolical, universal significance. Or he may even have gathered together enough food to be distributed by his disciples to the whole crowd. . . . But in any case he did or said something . . . . (Jesus, p. 42)

I wonder if Michael Grant ever suggested any other ancient person “must have done something” in order to rationalize a popular tale of a miracle. Hercules? Samson?

I could go on but this is surely enough to make the point. Michael Grant is writing like another New Testament theologian and not like an historian of any of the Caesars.

.

Lunatic, liar, or Lord?

To cap this all off, let’s return to Grant’s opening chapter where he calls upon C. S. Lewis’s precursor who uttered one of the earliest forms of Jesus having been either “lunatic, liar or lord”.

As J. Duncan wrote in 1870, ‘Christ either deceived mankind by conscious fraud; or he was himself deluded; or he was divine. There is no getting out of this trilemma.’ Perhaps not, but the admission that he was ‘deluded’, that his forecast proved wrong, is merely another way of saying what many others would accept: that in assuming human shape Jesus also took on human limitations. (Jesus, p. 20)

Of course not. Michael Grant is writing as an historian. We know he does not believe he was a fraud. Grant cannot say Jesus was divine. But he does say ‘in assuming human shape’ this historical person [Alexander, Romulus, Caesar, Paul, . . . . ] ‘took on human limitations’. Surely it is clear. Michael Grant at no point writes of Jesus as if he were even genuinely human, let alone historical.

And he relies entirely upon the esoteric, the arcane, methods of theologians to craft his portrait of this man he concedes was unlike any other in the history of the world.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Here is my work on this topic so far, with number four in this new series produced during the past couple of days, and then finished in the way it is now earlier today. I have been working on this problem mentally for the past seven years after being an intense theist since age 20 (I’m now 56) and brought up since age 4 believing the Bible. Number four is my way of solving the integrity or lunatic problem of a historical Jesus. Thanks so much for all of the info presented in the post above!

#2 Constructing The Real Jesus Series: Jewish Temples, the Abomination of Desolation, Mark’s Composition Time, and OT & NT Themes

https://www.facebook.com/AtheistStandardsForChildren?ref=ts&fref=ts#!/AtheistStandardsForChildren/posts/272075346258634

#3 Ten Tangibles For Constructing the Real Jesus

https://www.facebook.com/AtheistStandardsForChildren?ref=stream#!/AtheistStandardsForChildren/posts/272585162874319

#4 Constructing The Real Jesus Series: Did Jesus Believe in Miracles?

https://www.facebook.com/AtheistStandardsForChildren/posts/273726816093487

I find this to be an engaging article. I don’t know much at all about the author, other than he had some coursework in Polybius and Livy, so obviously he knows a good bit about classical history. Having had my own smatterings of training in both history and theology, I am impressed with the author’s thinking, because I have done my own thinking, and what he finds as the issues pretty well line up with what I find them to be. No, the Gospel writers weren’t historians; they were Christian propagandists, in the better sense of that word. They were promoting a new Way of life, and they cast their ‘pamphlets’ in the best possible light. Two of them (Matthew and Luke) evidently built their pamphlet on a third (Mark), and the Fourth (John) may or may not have built his on any one or all three of those. What I find to be lacking in such thinking as this author’s is the psychological aspect. He knows about Freud and the subconscious, so he is aware of the potential volatility available once psychology and the subconscious is brought into the discussion. I think that Jesus was centuries ahead of his contemporaries when it came to probing the subconscious with ambivalent, ambiguous statements, such that it was impossible for his “reporters” to keep up with any consistent way of reporting what He had said. By the time these reports were used by the Gospel writers, the confusion was worse confounded. Neither the orthodox Jews nor the early Christians could make head or tails of just where Jesus was “coming from.” The nearest any theologian has come to understanding Him, to my mind, is C. H. Dodd. Therefore, I wonder if The Jesus Seminar has really rendered Dodd “arcane.” Dodd makes more sense to me than Schweitzer, and I have studied the work of both men regarding the eschatology of Jesus’ teaching.