Twenty years ago the late Michael Goulder wrote an article in which he argued that Paul was the Fourth Gospel’s Beloved Disciple (“An Old Friend Incognito,” Scottish Journal of Theology, 1992, Vol. 45, pp. 487-513). It is no secret that the Fourth Gospel’s Jesus is very different from the Synoptic one. Goulder proposed that its Beloved Disciple too is a very different version of a disciple we all know and love: Paul.

According to Goulder’s hypothesis:

John was writing round the turn of the century, and had not known Paul personally. He did know at least some of the Pauline letters which we have; and he inferred from them, reasonably but erroneously, that Paul had been one of the Twelve Apostles. He also inferred from them that Paul had been present at the Last Supper, the Passion and the Resurrection. He found reason for thinking that Paul had been loved by Jesus; but his reconstruction was met with so much incredulity that he felt obliged to keep his hero incognito. (pp. 495-96).

Thus, according to Goulder, it was a misunderstanding of certain Pauline passages that led the author of the Fourth Gospel to form a conception of Paul quite different from the one in the Acts of the Apostles.

- The scholar suggested that the very expression “the disciple that Jesus loved” may owe its origin to a mistaken understanding of Gal. 2:20: “But the life that I now live in the flesh, I live in faith in the Son of God, who loved me . . .”

- And he noted how easily one could have wrongly inferred from the words of 1 Corinthians 9:1 (“Am I not an apostle? Have I not seen Jesus our Lord?”) that Paul, like the other apostles, had met and received his call to apostleship from Jesus during the time of the Lord’s public ministry.

One particularly interesting example brought forward by Goulder was 1 Corinthians 11:23 ff. (“For I received from the Lord, what I also handed on to you, that the Lord Jesus, in the night in which he was betrayed, took bread etc.”). Goulder showed that the Fourth Gospel’s peculiar Eucharistic scenario could have plausibly arisen from a misidentification of the two occasions referred to by the 1 Corinthians passage, to wit:

“I received from the Lord” when I reclined on his breast at the Last Supper . . . “that the Lord Jesus, in the night in which he was betrayed” after the Feeding of the Five Thousand, “took bread etc.”

In the Fourth Gospel the Beloved Disciple was present at the Last Supper, but there is no indication given that he was present at the earlier event. And in that gospel it is implied that it was at that earlier event—the Feeding in Jn. 6—that Jesus instructed his followers to observe a eucharistic eating and drinking. His eucharistic discourse is given on that occasion and, correspondingly, there is no eucharist celebrated at the Johannine Last Supper. Thus the Beloved Disciple would have learned from Jesus at the Last Supper what had transpired after the earlier event, the Feeding of the Multitude.

In this scenario, then, the betrayal by Judas was initiated on the earlier occasion, somewhat like the initial betrayal agreement in 14:10 of Mark’s Gospel. Which is why it was after the Johannine Feeding that Jesus spoke of the betrayal: “Did I not choose you twelve? Yet is not one of you a devil? He was referring to Judas, son of Simon the Iscariot; it was he who would betray him, one of the twelve” (Jn. 6: 70-71).

As Goulder sees it—and I agree—this kind of reading of 1 Corinthians 11:23 would explain quite well why the Fourth Gospel has the peculiar eucharistic scenario it does. (Again, I emphasize that Goulder is not arguing that the above explanations are the correct interpretations of the Pauline passages in question. What he is saying is that whoever wrote the Fourth Gospel could have composed it under the sway of such reasonable misunderstandings. And “the striking fact is that it is possible to find a basis for all the BD (Beloved Disciple) stories in the Pauline epistles, if that is what one is looking for.” (“An Old Friend Incognito”, p. 495).

Another example: John 21:23 mentions a rumor among the brethren that the Beloved Disciple would not die, but would remain until Jesus comes. It claims that the rumor was based upon a misunderstanding of something Jesus said. Now there are Pauline passages that could plausibly give rise to such a rumor. Goulder cites Philippians 1:25:

And convinced of this I know that I shall remain and continue with you all . . .

To which I would add 1 Thessalonians 4:15 where Paul says,

We tell you this, on the word of the Lord, that we who are alive, who remain until the coming of the Lord, will surely not precede those who have fallen asleep.

The “would not die” and “remain” of Jn. 21:23 can be seen as corresponding to the “who are alive” and “who remain” of 1 Thess. 4:15. The words of Jesus, “What if I want him to remain until I come” in Jn. 21:23 could have been taken to correspond to the “word of the Lord” in 1 Thess. 4:15. It is easy to see how, based on these passages, a belief that Paul would not die could arise.

One more:

In John 20:4 the Beloved Disciple outruns Peter to the empty tomb. Goulder suggests that this passage may be inspired by Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 9:26, “So that is why I run as I do, not aimlessly.” And taking this outrunning of Peter a step further, Goulder (and many other scholars too) detect an element of competition between the Beloved Disciple and Peter. As Goulder describes it:

At every step we seem to feel that he (the Beloved Disciple) is doing better than Peter—more intimate with the Lord, better connected (with the high priest), the first to believe in the resurrection, a faster runner, and so on.” (“An Old Friend Incognito” p. 495).

.

ADDING AN APELLEAN PERSPECTIVE

There is much in Goulder’s scenario that is persuasive. I think, however, that it is capable of being completed and its defects corrected with help from my own theory regarding the origin of the Fourth Gospel. Readers of my series of Vridar blog posts entitled “The Letters Supposedly Written by Ignatius of Antioch” are aware that in the last five posts of that series I argued that the author of the letters was an Apellean and that his gospel was some form of what became the Gospel according to John. I argued that canonical John is a proto-orthodox reworking of the “Manifestations” (Phaneroseis), the gospel written by the ex-Marcionite Apelles. This post will assume that those contentions are correct and will continue on to show how this theory can mesh with and fill out Goulder’s.

Apelles, as a former Marcionite, came from a background where “The Gospel” was viewed as Paul’s gospel. For Marcionites all the other apostles never really measured up. After Christ’s ascension the Twelve ultimately relapsed into a Judaized understanding of the gospel. Now there is no indication in the extant record that Apelles ever switched his allegiance, so to speak, from Paul to some other Apostle or disciple. He continued to use the Apostolicon:

He (Apelles) uses, too, only the apostle, but it is Marcion’s, that is to say, it is not complete. (Pseudo-Tertullian, Against All Heresies, 6).

And although he did create a new gospel with major input from his prophetess associate Philumena (whose name means ‘Beloved’), the ultimate source of that gospel was still apparently viewed as largely Paul. For Philumena claimed that the source of her information was a phantom (phantasma) who appeared to her

. . . dressed as a boy and sometimes stated he was Christ, sometimes Paul” (fragment from Tertullian’s Against the Apelleans, P.L. 42, 30, n. 1).

My examination of the Ignatian letters confirms this conclusion. They betray knowledge and use of a Johannine-like gospel but, sure enough, nowhere in them is there mention of John, the son of Zebedee. Not even in the letter the prisoner writes to the community at Ephesus—the city where, according to tradition, John spent much of his later life right up “until the time of Trajan” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 3.1.1). No, it is Paul who is praised in the Ignatian letter to Ephesus (IgnEph. 12,2). And although all agree that it was written in the second century, the apostle John does not show up alongside Paul in it or even receive a passing acknowledgment.

Now it might seem to be out of the question to identify Paul as the Beloved Disciple. After all, Paul was a persecutor of the early Christians, was he not? And didn’t his conversion to Christianity occur after Christ ascended back to heaven? But, remember, the persecutor scenario represents a proto-orthodox view of Paul, and Apelles came from a Marcionite background. Marcion rejected the Acts of the Apostles. And it is known that the verse in Galatians where Paul says he persecuted the church of God (Gal. 1:13) was not part of Marcion’s version of the letter. Apparently nowhere in Marcion’s Apostolicon was there anything about Paul being a former persecutor of the church (See Tertullian’s Against Marcion, 5,1).

Thus my Apellean theory can here lend support to Goulder’s hypothesis. An Apellean origin for the Fourth Gospel can explain both why Goulder’s Paul has the prominent role he does in that gospel and why “persecutor” is not part of his c.v.

.

WHY PAUL IS INCOGNITO

The Beloved Disciple, as Goulder recognizes, is quite a shadowy figure. The Fourth Gospel never clearly identifies him by name. And he first turns up, without introduction, more than halfway through the gospel: “It really is extraordinary to meet him for the first time at the Last Supper, reclining in the best seat on Jesus’ right!” (“An Old Friend Incognito”, pp. 494-495). Goulder supposes that it was the author who made his hero obscure. By keeping him incognito, the author hoped to avoid rejection of his new gospel by Jerusalem Christians who held that Paul was converted only after Jesus’ death.

The Beloved Disciple, as Goulder recognizes, is quite a shadowy figure. The Fourth Gospel never clearly identifies him by name. And he first turns up, without introduction, more than halfway through the gospel: “It really is extraordinary to meet him for the first time at the Last Supper, reclining in the best seat on Jesus’ right!” (“An Old Friend Incognito”, pp. 494-495). Goulder supposes that it was the author who made his hero obscure. By keeping him incognito, the author hoped to avoid rejection of his new gospel by Jerusalem Christians who held that Paul was converted only after Jesus’ death.

He therefore fell back on a simple expedient. He had no need to give the apostle’s name. He could let him remain incognito, and refer to him merely as ‘the disciple whom Jesus loved’. In this way his status as the favourite disciple could be repeatedly brought home, and his teaching duly legitimated. Those in his own circle would know whom he was referring to, and the ungodly would be given no occasion to blaspheme. (“An Old Friend Incognito”, p. 499)

But I find it hard to accept that explanation. It does not explain why the Beloved Disciple is missing earlier in the gospel. Could not the same expedient of referring to him merely as ‘the disciple whom Jesus loved’ have been used to describe, for instance, his call by Jesus? The calls of Andrew, Peter, Philip and Nathanael are there. Why not his? Could not the same expedient have been used to give the call of the Beloved Disciple the special attention it surely deserved?

Moreover, the shadowy portrayal of the Beloved Disciple is far from being the only problem with the current text of the Fourth Gospel. It shows many signs of dislocations and interventions. It is a rare Johannine commentator who can refrain from suggesting at least one rearrangement of the text to smooth over a rough spot.

I think, then, that my Apellean theory can better explain the sorry state of the text, including its unsatisfactory portrayal of the Beloved Disciple. The text was tampered with by the proto-orthodox redactor who reworked the Apellean gospel. It was he—not the author—who caused the obscurity. The proto-orthodox had their own scenario for Paul. They had already created a very different persona for him, one as a converted former persecutor of Christians. So they could not allow his persona as the Beloved Disciple in proto-John to remain intact. They hid his identity. But how?

I am convinced they did it by assigning one of the anecdotes about him (his call) to someone they named ‘Nathanael,’ and by assigning another one (his being raised from the dead by Jesus) to an individual they named ‘Lazarus’. Thus parts of his bio were severed from the rest of it and used to create Nathanael and Lazarus. In line with Goulder’s theory I will show how certain Pauline passages lend themselves to the kind of interpretation that reveal ‘Nathanael’ and ‘Lazarus’ as ciphers for Paul.

Note that this scenario in effect incorporates a number of particular proposals made previously by various scholars.

- As already noted, Michael Goulder proposed Paul as the Beloved Disciple.

- K. Hanhart is another proponent of that identification.

- H. Spaeth and M. Rovers held that the Beloved Disciple was Nathanael, and that identification has recently been argued by D. Catchpole.

- A. Hilgenfeld and O. Schmiedel held that Nathanael was Paul.

- H. Holtzmann argued that Nathanael was a symbol of Paulinism.

- E.F. Scott, in his The Fourth Gospel, says that “in the story of Nathanael the evangelist alludes symbolically to Paul.” (p. 48).

- In regard to identifying Lazarus as the Beloved Disicple, there are many scholars who have taken that position, including J. Kreyenbuhl, K. Kickendraht, B.G. Griffith, H.M. Draper, F.W. Lewis, F.V. Filson, J.N. Sanders, W.H. Brownlee, J.M. Leonard, V. Eller, M. Stibbe, and T.L. Brodie.

I submit that all of these scholars were partially right. What is needed is to combine their insights and complete them with the help that an Apellean perspective has to offer. The Beloved Disciple Paul was taken apart by the proto-orthodox redactor. He needs to be put back together again.

.

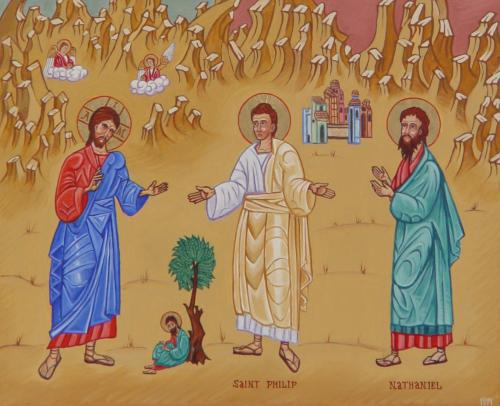

NATHANAEL

If one were to choose a Beloved Disciple just based on the call stories, I think practically everyone would choose Nathanael. More attention by far is given to his call. He is the only disciple who receives Jesus’ praise before he has even said a word: “Here is a true Israelite. There is no deceit in him.” And he is the only disciple in any of the four canonical gospels who believes in Jesus from the first moment he meets him: “You are the Son of God.”

If one were to choose a Beloved Disciple just based on the call stories, I think practically everyone would choose Nathanael. More attention by far is given to his call. He is the only disciple who receives Jesus’ praise before he has even said a word: “Here is a true Israelite. There is no deceit in him.” And he is the only disciple in any of the four canonical gospels who believes in Jesus from the first moment he meets him: “You are the Son of God.”

And Jesus is clearly delighted by his spontaneous faith in him; so delighted that he promises greater things to come, including a vision of “the sky opened and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man.”

Goulder, as noted earlier, called attention to how “at every step we seem to feel that he (the Beloved Disciple) is doing better than Peter”. I would argue that this is the case here too. Nathanael/Paul is the Beloved Disciple and his confession of faith that Jesus is “the Son of God” outshines Peter’s confession that Jesus is “the holy one of God.”

By identifying ‘Nathanael’ as the Beloved Disciple two difficulties disappear. After receiving such a grand introduction at the beginning of the gospel, he no longer completely vanishes from it until the very last chapter. And, correspondingly, the Beloved Disciple no longer just appears, without explanation or introduction, in chapter thirteen of the gospel.

And once we recognize that ‘Nathanael’ is just the proto-orthodox label applied to hide Paul’s name, we can understand why Jesus was made to vouch for his truthfulness. The words “there is no deceit in him” have in view statements of Paul like “The God and Father of the Lord Jesus knows… that I do not lie” (2 Cor. 11:31).

And the words of Jesus that foretell the disciple’s future visions (“You will see greater things than these. You will see the sky opened etc.”) look forward to Paul’s, “But I will go on to visions and revelations of the Lord” (2 Cor. 12:1). [The context makes clear that the vision was promised to Nathanael alone. But the proto-orthodox redactor apparently realized that the singling out of Nathanael for such a vision could provoke suspicion, so he awkwardly and sloppily made the “you” plural in the final sentence. That is, Jesus says to Nathanael, “You (singular) will see greater things than these. And he (Jesus) said to him (Nathanael), Truly, truly, I say to you (plural), you (plural) will see the heavens opened . . . ” etc.]

.

THE BOY DISCIPLE

The text I cited earlier about the source of the Apellean gospel contains an item that further strengthens the case for identifying Paul, Nathanael and the Beloved Disciple as the same person. The phantasma who appeared to Philumena and “sometimes stated he was Christ, sometimes Paul” came to her “dressed as a boy.” It seems reasonable to suppose there is some significance in the phantom’s appearance as a boy. It cannot be related to his being a voice box for Christ since, in Apellean and Marcionite belief, Christ descended to earth as an adult. But it would make sense from the standpoint of his being a voice box for Paul. For the name ‘Paul’ is the masculine form of the Latin word for ‘small’, ‘little’.

The text I cited earlier about the source of the Apellean gospel contains an item that further strengthens the case for identifying Paul, Nathanael and the Beloved Disciple as the same person. The phantasma who appeared to Philumena and “sometimes stated he was Christ, sometimes Paul” came to her “dressed as a boy.” It seems reasonable to suppose there is some significance in the phantom’s appearance as a boy. It cannot be related to his being a voice box for Christ since, in Apellean and Marcionite belief, Christ descended to earth as an adult. But it would make sense from the standpoint of his being a voice box for Paul. For the name ‘Paul’ is the masculine form of the Latin word for ‘small’, ‘little’.

But I think there is more than wordplay going on here. My suspicion is that, as Apelleans saw it, Paul, the Beloved disciple, had been the smallest disciple, a mere boy disciple of Jesus. And that ‘Paul’ was in fact an early nickname given to him precisely because he was only a boy when he became a disciple. Such a view could have arisen from a misunderstanding of 1 Cor. 15:9: “. . . for I am the least of the apostles.” And Eph 3:8: “Unto me, who am less than the least of the holy ones, is this grace given, that I should preach among the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ.” (my emphases). The word “least” in these passages can mean “small in size” and could be wrongly taken as a reference to a nickname received earlier in life.

In my opinion, seeing the Beloved Disciple as a boy makes better sense of several passages in the Fourth Gospel. At the Last Supper the Beloved Disciple reclined on the breast of Jesus. Johannine commentators assure us that such physical closeness between grown men was nothing out of the ordinary for the time and place that Jesus lived. Still, it seems to me that the incident makes better sense if the person lying on the breast of Jesus at the Last Supper was a child. It jibes better with what is said in Mark 9:36 about Jesus “taking him (a child) into his arms.”

The call of Nathanael, too, makes better sense if he was a child. The delight Jesus exhibits at Nathanael’s approach is reminiscent of the “Suffer the little children to come to me” episodes in the Synoptic gospels. And Nathanael’s expression of surprise that Jesus saw him under the fig tree makes me think of the typical surprise a child shows when, for instance, an uncle magically pulls a coin from the child’s ear: “How did you do that?!” And people have always wondered what Nathanael was doing under the fig tree. If he was a typical boy, he was doing what boys do under fruit trees: picking and eating fruit. And his words, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth” sound like many another boyish quip.

William Harwood, in his Mythology’s Last Gods, wondered whether Jesus’ words, “There is no deceit in him,” might be a hint that Nathanael was mentally retarded. I think it is rather a hint that Nathanael was an ingenuous child. And Jesus, by praising the boy’s candid nature, begins the defense of someone who later in life will be regularly calumniated as a deceiver by his enemies. Jesus is made to vouch in advance for Paul’s later veracity: “There is no deceit in him”.

To be kept in mind too is that the extant patristic record does retain some other traces of belief that the Beloved Disciple was not a young man, but a veritable boy. For example:

We maybe sure that John was then a boy (Latin: “puer”), because ecclesiastical history clearly proves that he lived to the reign of Trajan, that is, he fell asleep in the sixty-eighth year after our Lord’s Passion . . . (Jerome, Against Jovinianus, 1, 26)

.

NICODEMUS

“But,” one could reasonably object, “the Beloved Disciple seems to have been known to the high priest (Jn. 18:15). If the Beloved Disciple was a boy, how to explain that acquaintance?”

One possibility I see is by way of Nicodemus. He enters the narrative just a chapter after the call of ‘Nathanael’. And he seems to be the Fourth Gospel’s version of Gamaliel. He is described as a Pharisee and a ruler of the Jews (Jn. 3:1). Most Johannine scholars understand “ruler of the Jews” here to mean “member of the Sanhedrin”. And that the author of this gospel viewed the Pharisees as associated with the priests is spelled out, for instance, in Jn. 11:47: “So the chief priests and the Pharisees convened the Sanhedrin and said, “What are we going to do? This man is performing many signs.”

Jesus calls Nicodemus not just “a” teacher of Israel,” but “the teacher of Israel” (Jn. 3:10). We have, then, someone who, like Gamaliel, is presented as a Pharisee, a member of the Sanhedrin, and a singularly distinguished teacher of Israel. He comes “at night” to speak with Jesus, which is reminiscent of the ‘secret Christian’ status of Gamaliel in the Pseudo-Clementine Recognitions. And the reasoning of Nicodemus—that “no one can do these signs that you are doing unless God is with him” (Jn. 3:2)—has a certain affinity with the reasoning of Gamaliel in Acts of the Apostles: “But a Pharisee in the Sanhedrin named Gamaliel, a teacher of the Law, respected by all the people, stood up …. and said to them, ‘… if it comes from God, you will not be able to destroy them; you may even find yourselves fighting against God’” (Acts 5: 34, 39).

Now I acknowledge that the Johannine narrative establishes no explicit connection between a boy disciple of Jesus and Nicodemus/Gamaliel. But the topic of Jesus’ nocturnal conversation with the teacher of Israel was the need for rebirth from above in order to enter the kingdom of God. Many scholars recognize that this idea is basically the Johannine equivalent of the Synoptic “Amen, I say to you, whoever does not accept the kingdom of God like a child will not enter it” (Mk. 10:15; Mt. 18:3, my emphasis). That this verse has at some point been connected with the Beloved Disciple is witnessed to by Vatican codex 4222:

John, the most holy evangelist was the youngest among all the apostles. Him the Lord held (in his arms) when the apostles discussed who among them was greatest and when he said: `He who is not converted as this boy will not enter the kingdom of heaven.‘ It is he who reclined against the Lord’s breast. It is he whom Jesus loved more than the others and to whom he gave his mother Mary and whom he gave as son to Mary. (my emphasis)

(Robert Eisler, in his The Enigma of the Fourth Gospel, argues that the tradition behind this passage goes back at least to the late second/early third century CE).

So my suspicion is that the original text contained some connection between the boy disciple and Nicodemus/Gamaliel; that the boy was his pupil before his call by Jesus; and that it was he who told his Pharisee teacher about Jesus. In other words, I suspect that it was in proto-John that the story originated about Paul being “educated strictly in our ancestral Law at the feet of Gamaliel” (Acts 22:3). Thus the Beloved Disciple would have been known to the high priest (Jn. 18:15) because the boy had previously studied at the feet of the illustrious Nicodemus/Gamaliel.

.

LAZARUS

Lazarus is introduced suddenly in chapter eleven of the Fourth Gospel and is described by the words, “he whom you love” (Jn. 11:4). That description has caught the attention of many scholars and has understandably made Lazarus an intriguing candidate for Beloved Disciple. And he reclines with Jesus (Jn. 12:17), which of course the Beloved Disciple also does at the Last Supper (Jn. 13:23). It has always been troubling though, why there is not the slightest indication of ‘Loved Lazarus’ until so late in the narrative. The scenario I have proposed solves that problem.

Additional reasons why Lazarus makes such a good Beloved Disciple are

- that his home was in Bethany, near Jerusalem, so it would have been close enough to conveniently bring the mother of Jesus there after she was entrusted to him on Golgotha (Jn. 19:27).

- And his up-close and personal experience with grave wrappings could account for the Beloved Disciple’s insight in sizing up the situation of the wrappings in the empty tomb on the morning of the Resurrection (Jn. 20:5).

- Finally, his having already undergone death might explain how the belief arose that the Beloved Disciple would not die (Jn. 21:23).

Now it might seem that, if I am right about Nathanael’s status as a boy, there is no way that he can be the same person who is called ‘Lazarus’ in chapters eleven and twelve. For Lazarus is always viewed as being an older brother of Martha and Mary. But in fact there is nothing in the account to indicate the age of the brother. The pronouns are all masculine, but nowhere is the brother referred to as a man. There is nothing in the narrative to rule out his being a boy, the little brother—not the older brother—of Martha and Mary.

And his status as a boy would make his death all the more tragic and explain even better the grief of his sisters and of Jesus. Isn’t the death of the young considered to be among the saddest things in the human experience? Note how in the Synoptic accounts of raisings from the dead by Jesus the youth of the deceased is an element. Jairus’ daughter is a twelve year old “child” (Mk. 5:42). The widow of Nain’s son is a “young man” (Lk. 7:14).

So I see no reason why ‘Lazarus’ cannot be the continuation of ‘Nathanael’. The location of his home close to Jerusalem brings him close to his teacher Nicodemus/Gamaliel. In Acts 22:3 Paul says, “I am a Jew, born in Tarsus in Cilicia, but brought up in this city (Jerusalem).” The Johannine version of him was apparently from Cana in Galilee (Jn. 21:2), but brought up in Bethany (Jn. 11:1), just outside of Jerusalem.

But if the resurrected brother of Martha and Mary was the Beloved Disciple and ‘Lazarus’ is just a proto-orthodox substitute name to disguise his real identity as Paul, it would mean that Paul was believed, at least by some, to have been raised from the dead by Jesus. How could such a belief have arisen? Is there a Pauline passage, in line with Goulder’s theory, that could have easily been misunderstood to mean that Jesus had raised Paul from the dead?

I think there is a very likely candidate in the verse that stood at the head of Marcion’s and Apelles’ Apostolicon. The Marcionite version of Galatians opened with this verse:

Paul, an apostle, not from men or through man, but through Jesus Christ who raised him from the dead . . . (my emphasis)

Scholars of Marcionism routinely claim that Marcion must have interpreted this verse in a modalistic sense, namely, that Jesus had raised himself from the dead. Perhaps, but this attempt to read Marcion’s mind about the verse is really just a guess, and other scholars, including Hermann Detering, have pointed out that Marcion’s version of the Paulines also included a number of passages that clearly had Jesus being raised by the Father. In any case, it is easy to see how someone who used this reading of Galatians 1:1 (as presumably Apelles and Philumena did) could take it as saying precisely what it appears to say: that Jesus raised Paul from the dead.

.

BY ANY OTHER NAME

I will finish by tying up a loose end. I have argued not only that the Beloved Disciple was Paul, but also that ‘Paul’ was only a nickname. Which leaves the question: What was Paul’s given name believed to be?

I think the most likely answer is ‘John’. That is the name that came to be attached to the Fourth Gospel at least from the time of Irenaeus. And John was a common name, so it would not be cause for surprise that two of the disciples were thought to have shared it: John the son of Zebedee, and John nicknamed “the little one” (Paul). But I suspect that this latter John was also known by some Christians under another nickname, one which called attention to his alleged great longevity: “the Aged One” (Elder). Papias of Hierapolis (100 miles east of Ephesus), writing around 140 CE, knows of a John the Aged One, but makes no mention of a Paul. This is the opposite of what is in the Ignatian letters (Paul, but no John) which were written at about the same time and place.

The short-lived Apellean sect preferred to use the first nickname, Paul. The proto-orthodox, on the other hand, preferred to use either his given name, John, or—in the case of Irenaeus—his second nickname, the Aged One, as a way to make him distinct from the proto-orthodox version of Paul.

Roger Parvus

.

(I have reformatted some sections of Roger’s article for easier blog reading. — Neil)

.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“So I see no reason why ‘Lazarus’ cannot be the continuation of ‘Nathanael’.” Besides the fact that they have different names and their stories have nothing in common you mean. A whole lot of speculating in this post. Beware of theories that are on the lookout for facts.

It is speculative, yes, as any discussion of the identity of the Beloved Disciple must inevitably be, but it not without rationale drawn from the evidence. Nothing to “beware of”. This serves as an appendix to Roger’s series on the Ignatian letters. Articles that are tentative proposals for new ideas, speculative ventures that are not without support in the evidence, are valid enterprises and common enough, as the previous literature cited here [Goulder, Hanhart, Spaeth, Rovers, Hilgenfeld, Schmiedel, Holtsmann, Scott, Kreyenbuhl, Kickendraht, Griffith, Draper, Lewis, Filson, Sanders, Brownlee, Leonard, Eller, Stibbe, Brodie] testifies.

What is of interest in a theory is its explanatory power. Roger’s suggestion does make sense of a number of outstanding questions about the Gospel of John. That does not mean it is “true”. But it does allow it a place at the table for consideration.

Mark,

Unfortunately there aren’t any non-speculative solutions to the Beloved Disciple enigma.

As I indicated in my post, my starting point here was a conclusion I reached on other grounds: that proto-John was written by the ex-Marcionite Apelles and was converted by the proto-orthodox into canonical John. If so (and I realize that is still an “if”), the question becomes: How did the proto-orthodox carry out that conversion? I don’t see the plugging in of new names (Nathanael and Lazarus) as something that would be beyond them. The proto-orthodox were perpetrators of fraud and forgery on a massive scale (See Bart Ehrman’s Forged). I see no reason why the switching out of names would not also be in their fraud-and-forgery toolbox.

You protest that “they (Nathanael and Lazarus) have different names and their stories have nothing in common”. But there are mainstream scholars who have made a respectable case for Nathanael as Beloved Disciple, and other mainstream scholars who have made a similarly decent case for Lazarus. If a good case can be made that A = B, and also that A = C, the reason may be because B = C. I realize, of course, that the unquestioned assumption is always that the Beloved Disciple can be one named figure or another, but not both. But my theory is not bound by that assumption. For the substitution of new names may have been one of the ways the proto-orthodox hid the identity of Paul.

You wrote: “Beware of theories that are on the lookout for facts.”

True, but don’t dismiss out of hand a theory that can plausibly account for the facts. In this case, not just the facts that concern the portrayal of the Beloved Disciple (e.g. his anonymity, the absence of his call, his late and abrupt appearance in the narrative, his seat of honor at the Last Supper, the need to endorse his credibility in chapter 21, the rumor that he would not die). But also the facts that concern the Beloved Disciple’s Gospel as a whole (e.g. its lateness, its discontinuity, its dualism, its mildly gnostic character, its suppression of an Ascension scene, its exceptional antagonism to Judaism, its anti-docetism, its peculiar eucharistic scenario). I think a theory that can plausibly account for these merits consideration.

But is it really plausible to think that proto-John was written by an ex-Marcionite? I have given my reasons for that in another post. And there are bona fide scholars who have detected Marcionite elements in the Fourth Gospel. Among earlier scholars there was, for instance, Joseph Turmel. And among recent, Robert M. Price, who writes:

So I admit that my solution is speculative. And I acknowledge that in some particulars it is new. But that it is speculative is unavoidable . And that it is new I don’t see as a fault. Given the present impasse, I doubt the Beloved Disciple enigma will ever be solved without the help of some kind of new perspective. An Apellean origin for the Fourth Gospel might turn out to be the kind of perspective that is needed.

I appreciate the response. My comment probably didn’t deserve the lengthy response, but I will try to make it worth your while soon.

I think the issue is that you think there can be a solution to an enigma. But on specifics, your transitive property possibility would depend on the cases made that each name was the beloved disciple. Unless there is overlap or some relation between the two cases, then B won’t likely equal C because the two A’s are only trivially the same. Does that make sense?

The point of my warning is that theories looking for facts will pick and choose among them. I don’t know enough about gJohn to say whether you are cherry-picking facts, but I suspect that may be the case. Starting with a previous theory of yours and stretching it to cover a whole different problem is what makes me think that. You could be right, but I think it’s a longshot.

One can wonder. Trying to understand what went on to make the early documents what they are seems like trying to understand evolution of life-forms when we have nothing earlier than mammalian fossils. I wonder if Bayes theorem can be applied to this question. 😉

This also draws attention to those questions of the relationship between the Gospels of Mark and John, and those that ask if Mark was dramatizing a Pauline theology and if the young man in the tomb was a cipher for Paul.

But I also wonder about early Christian writings like Justin Martyr’s Trypho. We read there passages that sound quite like something from Paul and others from John but no hint of either name is ever raised.

Neil,

You wrote: “But I also wonder about early Christian writings like Justin Martyr’s Trypho. We read there passages that sound quite like something from Paul and others from John but no hint of either name is ever raised.”

My guess is that Justin knew the Pauline letters were reworked letters of Simon (a name he does raise several times) and so was wary of acknowledging them. Even with the name ‘Paul’ on them the reworked letters still contain a fair amount of Simon’s proto-gnostic ideas. It would be understandable if there was hesitation on the part of some of the proto-orthodox like Justin about the wisdom of trying to adopt/co-opt them—especially since Marcion had taken it upon himself to expose the tainted character of the letters.

Regarding the Johannine writings: As you know, I think they are of Apellean origin, and were largely based on the supposed revelations of Apelles’ prophetess associate Philumena. Again, I suspect that Justin knew of them and sparingly used material from them, but was careful not to acknowledge the source. It was probably only in the mid-150s that the proto-orthodox, with a push especially from Polycarp, decided to commit to a reworked, sanitized version of Apelles’ gospel.

Makes sense, and I should have understood that would be your response. It takes a while to think through all the ramifications of new ideas.

So, since “Paul” is really Simon Magus, it must be that both the proto-Orthodox and Apellean communities shared the misconception that he was named Paul? Are you suggesting that there was a real person, John Paul, who shared an appellation with Simon the Small, the author of the Pauline epistles? Or am I juxtaposing different ideas of yours that you developed over time?

No, I’m not suggesting there was a real first or second century John who was also Paul. I think that Apelles and Philumena believed Jesus was historical and had among his disciples one named John. And they believed that John became a disciple while still a child and, because of that, he acquired the nickname Paul. It was he, they thought, who later wrote the Pauline epistles. And it was he who years later, through a phantasm, revealed to Philumena the true gospel. He featured prominently in it as the Beloved Disciple.

I myself don’t subscribe to those beliefs. I’m inclined to think that there was a real first-century figure who at some point acquired the nickname Paul, but I suspect his given name was Simon and that he was from Samaria. He may have chosen the name Paul himself; or it was given to him by later followers; or perhaps the proto-orthodox imposed it when they reworked a Simonian letter collection. Hard to decide.

I think I misunderstood based on your description of Papias knowing of a John the Aged One. I know almost nothing about Papias but I assumed he was proto-orthodox.

The Apellean part of the hypothesis makes a great deal of sense to me. I’m trying to get my thoughts straight on how the proto-orthodox fit in. It must have been an awkward transition from the Apellean Paul the Epistlist-Evangelist (perhaps also named John) to the proto-orthodox Beloved Disciple presumed to be John the Evangelist and probably also John son of Zebedee but definitely not called Paul. If a proto-orthodox version of the text has lost all references to Paul or John but tradition has retained the connection to the name John (not to Paul).

If a proto-orthodox editor got hold of the Apellean version of gJohn full of references to Paul or John Paul, it seems an odd expedient to create the Beloved Disciple character, as well as Nathaniel and Lazarus, rather than change everything to John.

Greg,

I agree that, if the proto-orthodox did take in and turn the Apellean Gospel into GJohn, it must have been an awkward transition. And since the extant record provides few clear indications of this proposed scenario, I can only offer a few hunches:

I’m inclined to think that Apelles agreed to have his gospel modified and that he was one of those who turned away from Marcion to the church of God in the time of Anicetus (Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 3,3,4). That might in part explain why Irenaeus never mentions Apelles by name and never says a word about his particular errors.

And my suspicion is that the reason Apelles agreed to modifications of his Gospel was because Philumena at some point did something to cause him disillusionment. Tertullian says she “became a monstrous prostitute.” (I myself wonder whether the pericope about the adulteress in GJohn was added to that Gospel with her in view, by someone who knew of her role in that Gospel’s composition.) If indeed her reputation did take a hit, her credibility too would likely take a hit. Had she understood correctly everything the phantom told her? Had she unknowingly mixed truth with error? The Gospel based on her revelations might need to be sorted out, and Apelles may have agreed to let the proto-orthodox do the sorting.

Now, you write that “it seems an odd expedient to create the Beloved Disciple character, as well as Nathaniel and Lazarus, rather than change everything to John.” But I don’t think the proto-orthodox created the Beloved Disciple character. I think he was there from beginning to end in the Gospel of Apelles. He was there as a John, but with the understanding that he also had a nickname, Paul, that he acquired because he was a child disciple. So what the proto-orthodox had to do was modify the material enough that the Beloved Disciple would no longer be recognizable as the Apellean version of Paul. That entailed, among other things, taking some of his episodes (his call, his being raised from the dead) and changing the name on them (to a Nathanael and to a Lazarus). Readers would be allowed to keep the name John or put any name they liked—except Paul—on what remained of the Beloved Disciple figure. As it turned out, enough people remembered him as John that, as you noted, tradition has retained that name.

Another problem that the proto-orthodox would have had was: what to do about the phantom who supposedly was the means that the Beloved Disciple used to reveal the gospel to Philumena. They probably liked the idea of having a gospel that was dictated by one of Jesus’ disciples, but I expect they were not too keen on having it delivered by a phantom to a prophetess. Supposed phantoms are hard to control. And other self-claimed prophets might want to write gospels with the help of phantoms. So perhaps those were the circumstances that led to the proto-orthodox to change the “Beloved Disciple-would never-die” belief to the “Beloved Disciple-lived-to-an-extreme-old-age” fiction. Yes, the story would go, the Gospel did see light of day only recently, but that was because John was a very old man when he dictated it to someone (who was conveniently left unnamed).

It is worth noting that the ancient Antiochene tradition thinks Ignatius made an appearance in one of the gospel narratives. The Alexandrian tradition (Severus of Nesterwah) says that Jesus was making reference to Mark when he spoke about the mustard seed

Goulder was brilliant, though this is not his best guess. It does get one thinking about what the author(s) of John was/were trying to accomplish by writing yet another gospel. Paul exerts SOME force upon the gospel narratives, surely – but it is difficult to say precisely where and in what form.

I suppose I am wary of this hypothesis because sometimes it seems like John was written on another planet than the other three. I’m not even sure the author(s) of John knew who Paul was, or, if they had heard of him, thought much of him. .

I thought that the conventional wisdom held that the Book of Revelation emanated from an early stage of the “Johannine community” and that its attacks on “those who say they are Jews and are not”, “those who teach others to eat food sacrificed to idols”, etc were attacks on Paulinism.

But the evidence so often seems circumstantial. The strange thing is that Paul was such a divisive figure in the early second century, with a range of competing “biographies” suddenly appearing about him — Acts of Apostles, Acts of Paul and Thecla, Pastorals, and it’s when we first see the controversies over his collection of letters. He’s seen as the “real founder” of Christianity but nowhere appears in the external record until this late time. This does invite consideration that the name “Paul” is indeed nickname for someone who was also known by some other name for a long time. (The motif of “smallness” is a common enough one in “gnostic” literature.)

Paul was a real person who was known to many people along the routes of his missionary journeys. He stayed in several places for periods of time that lasted for many months. He wrote many letters (probably the overwhelming bulk of them have been lost) to his acquaintances. Therefore, the basic elements of Paul’s own story about himself was known to many people during his life and in the following decades.

In The Acts of the Apostles, we have a depiction of Paul that was written by an author who used the records and stories about Paul that were available and at least plausible for the author’s readers. This author writes very clearly that Paul never one of the living Jesus’s disciples.

So, how did the author of The Apostle According to John become convinced that Paul was one of the living Jesus’s disciples? Did he get the idea from other people who had some knowledge, stories or records about Paul?

Are we supposed to believe that there was one set of people who understood that Paul never had been a disciple of the living Jesus — and that there was another set of people who understood that Paul indeed had been a disciple of the living Jesus?

This is not a trivial difference of understandings about Paul. Rather, it is a fundamental difference of opinions.

I think this is kind of like trying to imagine that in ancient Greece there was one group of people who believed strongly that Pericles was an Athenian and another group of people who believed strongly that Pericles was a Spartan. It’s hard to imagine how such a fundamental difference of opinion about the man could have arisen and developed.

This is the conventional view of Paul according to the Church tradition.

But keep in mind that there is good reason to believe that the canonical Acts of the Apostles was not written until well into the second century.

Note further that the Acts of the Apostles does not tell us Paul was a letter-writer.

Note further still that around the same time another story of Paul appeared, one we know better as the Acts of Paul and Thecla. This presents a very different portrait of Paul from the one selected for our canon.

Note also that the Pastorals were written — also second century — in Paul’s name to give a quite different view of Paul from what we find in his letters.

It is difficult to try to imagine how someone might read Paul’s letters before any of this literature was ever produced.

Paul has seen/known Jesus prior to the Crucifixion:

1 Cor 9:1 Am I not free? Am I not an apostle? Have I not seen Jesus our Lord? Are you not the result of my work in the Lord?

1 Cor 15:8 and last of all, as to one untimely born, He appeared to me also

2 Cor 5:16 NAB Consequently,* from now on we regard no one according to the flesh; even if we once knew Christ according to the flesh, yet now we know him so no longer.

Gal 6:17 Finally, let no one cause me trouble, for I bear on my body the marks of Jesus.

… maybe Jesus struck Paul, as well, with a knotted cord, mortification aside.

Gal 3:1 You foolish Galatians! Who has bewitched you? Before your very eyes Jesus Christ was clearly portrayed as crucified.

… in this last, Paul speaks to Greeks who were in Jerusalem for Passover at the time of the Crucifixion.

Not one of the verses you cite says that Paul saw or knew Jesus prior to the crucifixiion. Your last verse does not give any indication that those he spoke to (Jews, not Greeks) knew anything about a crucifixion of a man at Passover in Jerusalem.

You are so indoctrinated with the Gospel story as a fact that you see evidence or proof for your story where none exists.

As I recall, J.B.Phillips in the intro to his New Testament in English (that I read in 1968), quoted a single ‘Paul-saw-Jesus’ verse like one of the above and suggested that he thought it pleasant to imagine the possibility of such an occurrence . So I dug up a few more, finally, this year.

As well, I felt uneasy using the word “Jews” when describing Paul’s Galatian audience “who were [more correctly: “had been”] in Jerusalem for Passover…” .

And, I opened with an inappropriate declaration, “Paul has seen/known Jesus…” when I should have had, “Paul may have seen/known Jesus…”

Thank you for the pertinent corrections!

Mike,

You wrote: “It’s hard to imagine how such a fundamental difference of opinion about the man could have arisen and developed.”

It would be hard to imagine how such a fundamental difference of opinion about Paul could have arisen if indeed, as you say, the basic elements of Paul’s life had been known to many people for many decades. I myself don’t think that they were. I think the name “Paul” saw light of day only around 130 CE when a proto-orthodox Christian put that name on some Simonian letters (letters of Simon of Samaria) as part of the changes made to co-opt those letters for proto-orthodoxy. Up to that point the Simonian letters would have been strictly internal documents. Simonians were known for their secrecy.

Assuming this is correct, it would mean that for people converted to some non-Simonian branch of Christianity after 130 (people like Marcion, Apelles, Philumena), the only way to piece together the life of the newly discovered Paul was by examination of the doctored letters themselves. [I agree with those who date the canonical version of Luke, Acts of the Apostles, and the Pastoral letters to around 150 CE. See, for instance, Robert M. Price’s The Pre-Nicene New Testament, pp. 497-98]. And, as Goulder points out, if someone were to form their conception of Paul only from the Pauline letters, he or she could easily end up with a portrait different from what became the orthodox one. One could easily (mis)take his call by Jesus to have occurred during the time of the Lord’s public ministry, and that important initial error would lead to others.

As I mentioned in my post, I find Goulder’s theory to be a particularly strong in its explanation of the Fourth’s Gospel’s unique eucharistic scenario. Ask yourself: If you thought Paul had already been a disciple during the lifetime of the Gospel Jesus and present at the Last Supper, how would you interpret this verse:

If you identify the time and place that Paul “received this from the Lord” as the Last Supper, you almost necessarily have to push forward the time and place of the institution of the eucharist to some earlier occasion. Which is what the Fourth Gospel does!

Thank you, Roger, for your thoughtful reply.

As I pointed out, your explanation indicates that there were two strong and fundamental opinions about Paul’s relationship to Jesus disciples — 1) Paul definitely was one of them, and furthermore he was “the beloved disciple”, and 2) Paul definitely was not one of them and furthermore he persecuted them.

I could accept rather easily that either of the two ideas might have become established, but not both of them.

That is my sticking point on your otherwise thought-provoking thesis.

Mike,

You wrote: “I could accept rather easily that either of the two ideas might have become established, but not both of them.”

To clarify: I do not claim that both ideas became “established”. As I explained in my 10th post on the Ignatians, I think the Apellean community was small in comparison with the proto-orthodox and Marcionites communities. And the Apellean community was short-lived. They appear to have existed as a distinct community only for about 15 years. Irenaeus makes no mention of either Apelles or Apelleans anywhere in his five volume treatise Against Heresies. So my guess is that the ex-Marcionite Apelles and his community were part of the reconciliation that occurred in the mid-150s:

Any reconciliation would have entailed submission of the Apellean gospel to proto-orthodox correction. This means that the Beloved Disciple was Paul only from his creation around 140 CE until around 155. At that point the proto-orthodox altered the Beloved Disciple in the way I described in the post, and in doing so turned him into the shadowy figure he remains to this day.

So the Apellean view of Paul never became established. It lost out quite quickly to the proto-orthodox one.

I don’t recall who/what put me onto this article, but I’ve had it on my computer for a coupla months and finally read it yesterday. Googling to see if it had been quoted, I ended up here again. Fancy that.

I like how your Appellean/Marcionite hypothesis explains the issue of Paul’s persecution, that Goulder himself brought up. Does that take care of ” I saw none of the other apostles—only James, the Lord’s brother.” as well?

Isn’t the standard view that the story of the resurrection of Lazarus is an expansion of Luke’s parable with its ““He said to him, ‘If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.’””? That’s not a big problem, since a redactor could easily have made the inspired choice of using the name “Lazarus” upon reading a story of some risen from the dead as a sign.

But what about the name “Nathanael” (Given of God?)? Any good ideas as to where that name may have originated?

I tend to disagree that ‘Paul”s name need have been John. The standard explanation seems to be that that is the only name left among “The Pillars”, when removing the dead ‘James the Just’.

Doesn’t it make more sense the other way round? After all, we’re assuming John uses parts of Luke/Acts anyway. It’s possible that borrowings travelled both ways during transmission, of course, but I don’t see that it’s necessary.

My biggest problem is the suggestion that the BD as very young if not a boy. I know that’s not original to you, but it’s problematic when associated with Goulder’s work. According to him, the length of Jesus’ ministry in John is predicated on the BD/Paul being absent for three years immediately after his call (Gal. 1.18).

A very young boy going (alone?) to Arabia as an apostle stretches my imagination. Why would he have been believed? It seems to me that one or the other idea has to go, for the story to be consistent.

–o–

I’m curious about you’re very late date for Acts. Pervo (for all his other faults) proposes c. 115, and that’s already later than most mainstream, I think. Wouldn’t anything written later than Bar Kokhba be expected to take into the account the far more thorough destruction of Palaestine, killing of Jews and outlawing of Judaïsm?

1. Jens, you wote:

First, by putting “alone?” in parentheses, you indicate you are aware that the word “alone” is not in the text of Gal. 1:17 as it currently stands. That omission leaves open a scenario whereby the boy disciple’s trip to Arabia was with someone else (with family? with an older sister or relative, for instance?). And if he was accompanying someone older, the purpose of the trip could have been unrelated to evangelization. You say that the idea of a boy going to Arabia “as an apostle” stretches your imagination. It would stretch mine too, but the words “as an apostle” are not in the text. True, Goulder (and some other scholars as well) interpret the verse to mean that the trip to Arabia was for evangelization purposes. But the text doesn’t explicitly say that. So, again, a scenario is left open whereby the boy was in Arabia for some other reason but, while there, received his Gospel revelations. (I would not entirely rule out, however, the possibility that the boy went alone into Arabia to receive those revelations. At least some early Christians apparently had no problem with John the Baptist being prepped in the desert for his mission from a young age: “The child grew and became strong in spirit, and he was in the desert until the day of his manifestation to Israel” – Lk. 1:80. So I’m not sure they would have balked at sending there too a solitary boy wonder Beloved Disciple to receive his formative revelations.)

This scenario would explain how Paul could both be called by Jesus himself during the Lord’s public ministry yet be so insistent in his letters that he had received his Gospel via revelation. Because he was away in Arabia for most of the three years that Jesus was teaching the other disciples, the Gospel that Paul received was by way of revelations. As you know, I think Nathanael’s call is the call of Paul. So that may be why Jesus immediately tells him he will see visions: “You will see the sky opened and the angels of God ascending and descending…” (Jn. 1:51). The Apellean Jesus knew his delightful Beloved Disciple would be absent for most of his public ministry (from Jn. 2:1 up to Jn: 11:1). But—-not to worry-—he received the gospel via revelations in Arabia!

2. You also ask:

Short answer: No. But according to the Encyclopaedia Biblica there was a scholar in the mid-1800s, H. Spaeth, who argued that Nathanael was the Beloved Disciple and that “Nathanael is synonymous with Johanan” (vol. 3, p. 3339). I haven’t read his argument. And I don’t know Hebrew. But I notice that James Charlesworth, in his The Beloved Disciple, says this about Spaeth:

3. And you write:

I think John Knox was right in dating Acts to the 150s. And, in line with Joseph Tyson’s theory, I think that whoever wrote Acts also reworked an earlier version of GLuke and, by means of the prologues, tied the two together.

I’m not surprised that the Bar Kokhba events are missing from Acts because I think the author wanted to make his work look like it was written in the early 60s. On this matter I find myself agreeing with James Tabor:

And with Bart Ehrman:

Re 1: Good point. One thing is what Paul means, but upon rereading, it is of course perfectly possible to read it as a just a journey, not an apostle’s mission.

I was about to suggest that identifying Lazarus with the BD wouldn’t work, if the BD is supposed to be Paul, but checking just to make sure, I realised the the Lazarus story is the last great sign before the final Passover, so the identification with a Paul newly returned after three years makes perfect sense. This idea of Goulder is really growing on me. It does have very good explanatory power. I just hate that I can’t see how to test it – it’s still too much a Just-So story for comfort.

I’ll have to look at Know and Tyson, I guess. I haven’t read Pervo’s Rethinking the Unity, but I’d need to see some convincing evidence against their being written by the same author in succession.

Of course I didn’t mean reference to it having happened, but it should really appear in prophecy. If the war of 66-73 formed the basis for Marcan apocalypse, why not incorporate the even larger destruction of Bar Kokhba in prophecy if writing after that event?

1. Regarding Knox’s position on the dating of Acts: You might also find helpful an article by John Townsend (“The Date of Luke-Acts”) in the book Luke-Acts: New Perspectives from the Society of Biblical Literature Seminar, edited by Charles Talbert. Townsend concludes that:

2. You ask:

Perhaps because inclusion of it in Acts would complicate the presentation of one of the author’s themes: that many Roman officials were favorably disposed to the first Christians. The inclusion of a prophecy about the 130s killing of Jews in the Bar Kokhba uprising and the outlawing of Judaïsm would not appear to significantly advance the cause of favorably distinguishing Christians from Jews, for Christians themselves were going to be facing violent treatment from Rome at about the same time. Justin is a roughly contemporary witness that, at least at Rome, Christians were being arrested and punished for being Christians: “If anyone acknowledge that he is a Christian, you punish him on account of this acknowledgment” (1st Apologia, 4). So it might have gotten a bit sticky for the author of Acts to prophetically bring in Rome’s future punishment of the Jews in the 130s as divinely willed without also getting into why its future violence against Christians would not be. And, of course, all the while trying to maintain his “purposeful ploy” (that he was writing in the early 60s). For these reasons the author may have judged it better to keep things simple and leave all reference to the later developments out of his story.

I wonder if some connection was intended to Dositheos, who was sometimes called Nathaniel (which makes him the only notable Nathaniel of that era that I know of other than the apostle called in the Gospel of John). Dositheos and Nathaniel mean the same thing, as do several other familiar Hebrew names, viz Jonathan and Matthew. I don’t know Hebrew myself, so maybe I’m dead wrong, but my BS detector starts buzzing when I read that Nathaniel and John (“Yohanan”) are equivalent names, because it implies that the author has confused the names John and Jonathan. It’s possible that the proto-Orthodox redactor of John made the same mistake himself.

Or was someone at some point trying to make an elaborate metaphor using the names Saul and Jonathan? That’s quite a stretch, I’d admit, based on what we know at present.

It’s interesting that there’s one name missing from this view of possible candidates for who Paul was as “the beloved disciple”…MARK.

John Mark.

Huller has tended to explore the Mark as Paul scenario fairly thoroughly…and had a look at the Secret Mark phenomenon as part of that. Secret Mark makes clear where the Lazarus story might really have come from.

Acts of the Apostles is the book that consigns John Mark away from Paul and makes them separate people. But since Acts comes more from Ignatius/Polycarp/Peregrinus Proteas…it might well be that we’d have to go over to Alexandria for a better view.

Alexandria figures bigger in the Gnostic world. Mark is supposed to have been the founder of the Alexandrian church…which has a heap of people who are NOT proto-Catholic till at least the late-second century.

Gnostic groups and an Alexandrian perspective are usually marked by variants of the Mark name. Whether that’s Marcion, Marcus, Marcellina, Marcellus. The proto-Orthdox/proto-Catholics especially have a go at heresies to do with the Markan name…but also hint that the heresies thought it was really Mark who was being called Paul.

There’s also something Huller brought up about one account saying John Mark was actually a resident of Jerusalem or at least somewhere close by.

I tend to see a huge amount of competition between Alexandria and Antioch…much akin to the stuff that had been going on LONG before…let’s face it, only a few hundred years earlier there’d been all this arguing between the Ptolemaic and Seleucid empires…and it was probably a rivalry still extant even under the Romans.

So Ignatius/Polycarp/Pegrinus claims he knew the Apostle John. I USED to think Polycarp was a valid remainder of something genuine UNTIL I read on Peregrinus. Now I’d have to consider him in all three of his names as a charlatan. So I have to treat his idea of being associated with John as absolute proverbial.

I still have to look at Hullers viewpoint that the name Marcion was actually a derivation of Aramaic that meant “those of Mark.”

So it’s still pointing back to Mark a lot.

When one considers that a Markan viewpoint and the Alexandrian view was earlier than proto-Orthodoxy…it makes even more sense of “Polycarp’s” comment about Marcion. “Recognize US, Polycarp” is one account of the supposed discussion. Which if the Alexandrian community of Mark had been first, meant saying to Ignatius/Polycarp/Peregrinus to recognize the authority of the earlier church. Ignatius/Polycarp/Peregrinus would then be a rebel…might swipe a copy of “secret Mark”, head up to Rome and start spouting his own stuff…and definitely try to have an impact in Antioch with his spiel about a “John” who was a disciple…and come up with things like Acts or at least instigate the events that led to Acts and other later books.

It’s interesting that on the definite identification of Peregrinus as Ignatius/Polycarp, I’m veering toward a pagan writer’s version of events. That writer was an eye-witness and wrote closer to the events.

I should clarify the above better.

Pretty much anything associated with Ignatius/Polycarp/Peregrinus was more around areas like Antioch, Epheseus, north of the Holy Land, even though records indicate he travelled to both Alexandria and Rome.

Antioch seems to have favored the books/letters NOT found in the Marcionite Gospel/Apostle…and the viewpoint of Ignatius/Polycarp/Peregrinus.

So there are competing groups. Clearly. Antioch versus Alexandria. Antioch definitely wanting to underplay Mark’s role as “beloved disciple.”

If we look at Mark (or John Mark) through the lens of Acts, he’s a minor player. Relegated to being a mere translator of Peter.

But as Marcionites tell us…Acts wasn’t part of what they had as a Gospel/Apostle scripture set.

On the Alexandrian side of things, Mark’s role looks much bigger.

John Versus Paul.

Part of a large blog by James David Audlin and his book pub.2014.

http://audlinbooks.com/category/bible/

I suppose Acts 14:19-20 could support the idea that Paul died and was raised up: “But Jews came from Antioch and Iconium, and having persuaded the crowds, they stoned Paul and dragged him out of the city, supposing that he was dead. But when the disciples gathered about him, he rose up and entered the city, and on the next day he went on with Barnabas to Derbe.”

The root of the incident in Acts 14 seems to be 2 Corinthians 11:25. where Paul mentions that he was stoned once, without specifying a time or place, sometime during his long missionary travels.

Acts has an awkward transition there, since Paul is with Barnabas immediately before and immediately after, but Barnabas is missing from the stoning itself (as are those “disciples” ex machina). Paul being alone in the lurch does match 2 Corinthians, though, where Paul mentions no other victim, only himself, at whatever stoning he’s talking about.

Overall, Acts 14’s quicky transition from Paul being proclaimed a god to being executed, explained by having some “Jews” show up to flip the ever-fickle crowds is all suspiciously Passion-Lite. If so, then naturally in a Christian fable, there’s a Resurrection-Lite to follow.

Good points. The Jesus narrative finds many variations.

Perhaps this is why Simon Magus is called the “standing one.”

Or Nathanael could be Dositheos the Gnostic who (according to Simonian opinion) submitted to Simon, but perhaps didn’t according to his own adherents. And perhaps the Simonians where part of a larger Samarian Christian continuum that not only accepted Simon the Samarian, but also Dositheos and other disciples of John the Baptist.