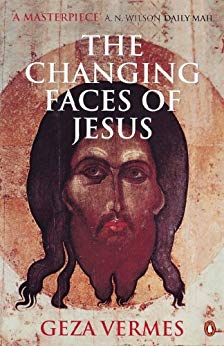

Géza Vermes is not a mythicist. He believes in the historical reality of Jesus to be found beneath the Gospels. But in the context of any mythicist debate what he writes in The Changing Faces of Jesus about the “myth” of Christ Jesus in Paul’s writings is noteworthy. It shouldn’t be. What he writes is noncontroversial. What makes his remarks noteworthy in the context of a mythicist debate is that he is not addressing mythicism at all and so his comments are not tainted with anti-mythicist polemic.

Géza Vermes is not a mythicist. He believes in the historical reality of Jesus to be found beneath the Gospels. But in the context of any mythicist debate what he writes in The Changing Faces of Jesus about the “myth” of Christ Jesus in Paul’s writings is noteworthy. It shouldn’t be. What he writes is noncontroversial. What makes his remarks noteworthy in the context of a mythicist debate is that he is not addressing mythicism at all and so his comments are not tainted with anti-mythicist polemic.

Consequently readers interested in an honest debate are free to see where traditional mainstream scholarly views and mythicist arguments do in fact coincide. One also encounters a reminder that certain stock responses to mythicist arguments are akin to tendentious “proof-texting”.

There are more things in the mainstream scholarly literature, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your stock anti-mythicist proof-texts.

Firstly, why are Paul’s views so significant? Vermes writes:

Paul can be seen as the father of the Jesus figure which was to dominate as the true founder of Christian religion and its institutions, and even such a sound and solid publication as The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church describes Paul as ‘the creator of the whole doctrinal and ecclesiastical system presupposed in his Epistles’. (p. 59)

Who was Paul? What do we know about him and how do we know it, as the familiar title now goes? Vermes again:

Who, then, was this true founder of Christianity? He always calls himself Paul, but in the Acts of the Apostles he is also known under the Jewish name of Saul. Acts 13:9 makes the identification explicit: ‘Saul who is called Paul’. According to the repeated testimony of Acts, he was born in the city of Tarsus in Cilicia (southern Turkey) and was a Roman citizen by birth. . . . . (p. 60)

Note that the above is learned from Acts which many scholars view as a propaganda narrative aimed at making Paul acceptable to “proto-orthodoxy”.

What do we learn from the letters said to be by the man himself?

Paul himself never refers in any of his letters to his birthplace or his citizenship; this silence is astonishing if these two factors played as important a part in Paul’s story as the author of the Acts of the Apostles implies. (p. 60)

So we see scholarly “astonishment” at the “silence” of Paul expressed here and it is about what we think we know about Paul from other non-Pauline sources. This silence is not quickly dismissed in Vermes’ discussion:

Paul describes himself as a Jew of the tribe of Benjamin and an adherent of the religious party of the Pharisees (Rom. 11:1; 2 Cor. 11:22; Phil. 3:5). Acts 22:3 adds that he studied in Jerusalem ‘at the feet of Gamaliel’, one of the leaders of the Pharisees in the first half of the first century AD. Nevertheless, Paul’s persistent silence on the subject adds a question mark to the validity of the information included in the Acts. A little boast (and he was certainly not averse to boasting), such as “I am a former pupil of the famous Gamaliel’, might have helped him in his disputes with Jewish legal authorities. . . . (pp. 60-61)

Now there is something interesting here about Vermes’ scepticism and argument “from silence”. Is Vermes’ point and logic valid? Should we be surprised at Paul failing to utter a little boast to the effect that he had been a pupil of the renowned Gamaliel in order to give his argument some extra lift over his Jewish opponents?

Is it only valid since it applies here to a question of Paul’s own personal experience? Vermes does not confine the logic of the quandary to this. On page 73 Vermes observes that a similar silence in relation to what Paul must have known about the “historical Jesus'” teaching on divorce is significant:

However, his [Paul’s] argument for celibacy would have gained considerable strength if he had pointed out that Jesus, too, was wifeless. His refusal to touch the subject may derive from his unwillingness to know anything of Christ ‘according to the flesh’.

As I will show later, far from arguing that Paul’s silence on the “historical Jesus” is the consequence of the occasional nature of the letters (an argument refuted by the occasions, as here, when the letters do indeed beg for reference to “the historical Jesus”!) Vermes argues that Paul’s silence is consciously deliberate and self-serving.

How topsy-turvy was Paul in his handling of scriptures?

Like the author of the Dead Sea Damascus Document, Paul was perfectly capable of turning the meaning of a scriptural passage topsy-turvy and arguing that the Jews were the children of Hagar, Abraham’s concubine, and Christians the children of Sarah through Isaac (Gal. 4:21-31). (p. 61)

Paul’s Achilles’ heel: his apostolic status

Paul’s Achilles’ heel was the questionable nature of his status as an apostle. He himself was convinced he was

- an apostle of Jesus Christ (1 Cor. 1:1; 2 Cor. 1:1)

- a servant of Jesus Christ, called to be an apostle (Rom. 1:1)

- one of the ‘ambassadors for Christ’ (2 Cor. 5:20)

- or more precisely ‘a minister of Christ Jesus to the Gentiles’ (Rom. 15:16)

(p. 64, my formatting)

Paul’s own “resentful polemic” makes it clear that the above claims were disputed by many others in “the church”:

‘Am I not an apostle? If to others I am not an apostle, at least I am to you, for you are the seal of my apostleship’ (1 Cor. 9:1-2). Elsewhere he denied any inferiority to those preachers he ironically called ‘superlative apostles’ (2 Cor. 11:5; 12:11). (p. 64)

Vermes identifies two sources for this opposition to Paul’s apostolic status:

- Jewish Christians in Palestine led by James who opposed Paul’s allowing Gentiles to bypass the Mosaic Law and saw Paul as “a self-promoting upstart”;

- Paul’s inability to accept the primitive Church’s definition of an apostle as one who had been with Jesus from the time he was baptized by John the Baptist (Acts 1:21-22).

Paul, who had never set eyes on Jesus or John the Baptist, would have failed the qualifying examination. (p. 64)

(Vermes runs into a little difficulty when he points out that the same letter in which Paul makes some of his most strident boasts also contains a line attempting to undo that very arrogance:

He was prepared to designate himself ‘the least of the apostles’ and in an off-guard moment to go as far as to declare that he was ‘unfit to be called an apostle’ (1 Cor. 15:9), yet in his heart of hearts he was ready to give his life for his apostolic title; despite paying lip service to humility, he did not hesitate to clash with his senior colleagues. (p. 64)

I think there are simpler explanations that involve the treatment this whole section as an interpolation. As noted by William O. Walker Jr. in Interpolations in the Pauline Letters:

serious questions have been raised regarding the authenticity of such passages as . . . 1 Cor. 15:3-11 . . . (p. 19)

It is also worth noting that Walker’s same list includes Gal. 2:7-8.)

Paul’s answer 1: supernatural visions

Keep in mind that this psychological portrait explaining why Paul stressed the need for visions and a supernatural (not historical or earthly) Jesus is Geza Vermes’ interpretation of the evidence. I am saving the “question time” till the end of this little presentation.

Knowing that he could not designate himself an apostle along traditional lines, he emphasized instead that he had been directly chosen by the will of God (1 Cor. 1:1; 2 Cor. 1:1; Gal. 1:1), or through a supernatural vision: ‘Am I not an apostle? Have I not seen Jesus our Lord?’ (1 Cor. 9:1); and later, ‘Last of all, as to one untimely born, [Christ] appeared also to me. For I am the least [i.e. the most recent] of the apostles’ (1 Cor. 15:8-9). (p. 64)

The statement in 1 Cor. 9:1 where Paul uses of himself the same word for “seeing” Jesus as he applies to the other apostles can only mean that he is saying that his “seeing” Jesus in vision is qualitatively as valid as anything experienced by the other apostles. (Some would argue that the implication is that Paul is implying that the other apostles “saw” Jesus in the same way he did, in vision — only?)

Having cast doubt above that we can have 100% confidence that the 1 Cor. 15-8-9 passage is original to Paul, we nonetheless have another passage in that composite epistle, 2 Corinthians, where Paul speaks directly of his Chariot or Merkabah mystical visionary of ascent to heaven. Vermes discounts this on the ground that it was not a description of Paul’s initial conversion. But others such as Alan Segal do allow for the possibility, if not strongly so, that this was the case. Either way, it is clear Paul had visionary experiences to boast about.

As a result, Paul felt fully commissioned by Jesus, needing no appointment but only recognition by the earlier apostles. (p. 65)

I do not fully grasp why it is insisted that Paul would have craved “recognition by the earlier apostles”. But I did say that I would hold off question time till the end.

Paul’s answer 2: a non-historical Jesus

While trying to maintain that he had the full status of an apostle, the fact that he had to admit he was not one of them from the start — even from the days of John the Baptist — imposed on Paul a very serious handicap. He had no contact with the earthly Jesus; he did not hear his teaching or experience his spiritual presence and influence. Intelligent as he was, he bypassed this dangerous terrain and devised a new, non-historical approach to the Lord Jesus Christ which contained no obvious disadvantage for Paul himself. (p. 67)

Vermes looks at a few passages by Paul that he says he took from earlier (presumably sanctioned by other apostles) “oral tradition” and I will look at those later, but Vermes does stress — and this is to support his interpretative narrative that Paul was motivated to establish his authoritative independence alongside the other apostles — that these traditional teachings passed on by Paul . . . .

. . . . quantitatively . . . do not amount to very much. Indeed, his gospel in no way resembles the account of the teaching and life of Jesus which in subsequent decades evolved into the Synoptic narratives. His preaching was not built on what Paul had heard from his predecessors; it relied on heavenly communication and visions. ‘When he who had set me apart before I was born, and had called me through his grace, was pleased to reveal his Son to me, in order that I might perch him among the Gentiles, I did not confer with flesh and blood, nor did I go up to Jerusalem to those who were apostles before me’ (Gal. 1:16-17). In other words, Paul did not solicit tutorials, convinced as he was that he knew all that he needed to know. Nor did he endeavour, as the evangelists did, to rehearse and reinterpret the story and the preaching of Jesus; his task was to reveal to the world the divinely designed meaning and purpose, and the achievements, of the crucified redeemer and saviour of mankind. (p. 69)

So what do we know of the historical Jesus from Paul’s letters according to Vermes?

After a meticulous combing of the whole corpus of his writings, the information relating to the prophet from Nazareth would add up to precious little. It would yield

- no chronological pointer of any kind.

- We would search for Galilee, its towns and villages, in vain; geography was of no interest to Paul.

- There is no mention of King Herod or his sons,

- of any of the high priests by name,

- not even Pontius Pilate.

- Mary and Joseph are ignored,

- though the brother of Jesus, James, is referred to twice in his apostolic capacity.

- John the Baptist is never alluded to.

- No apostle is named, apart from ‘Cephas and James’ on one occasion, and ‘James, Cephas and John’ on another, and Peter is said to be in charge of ‘the gospel for the circumcision’ . . . (Gal. 2:7).

Comparison with the detailed list of Paul’s friends, colleagues, and companions proves that he did not live in an abstract dream world, and that his silence of Jesus’ entourage was deliberate. (p. 70, my formatting and bold)

What, what? Is this a legitimate argument? Can it be that a scholar reputed to be “the greatest Jesus scholar of his time” can seriously suggest that Paul’s omissions of such things was deliberate — and therefore cannot be explained by the mere happenstance or occasional nature of the epistles?

This was hardly a slip of the pen. Vermes repeats:

In fact everything seems to suggest that in order to emphasize the paramount importance of the Jesus revealed in visions, Paul deliberately turned his back on the historical figure, the Jesus according to the flesh, kata sarka.

Vermes says that all we learn from Paul about the historical Jesus is that

- he came from the Jewish race (Romans 9:5)

- he was descended from Abraham (Galatians 3:16)

- he was of the line of David “according to the flesh” (Romans 1:3)

- he was “betrayed and died on the cross before rising from the dead and appearing to . . . apostles and disciples, and finally to Paul” – – –

- – – – And in the next chapter Vermes adds that Paul informs us “that [Jesus] was born of an unnamed Jewish woman (Gal. 4:4).

This is not really quite correct. What we read in Romans 9:5 is that it is from the Jewish nation that the idea of the Jews being the covenant people and the idea of the Messiah have arisen and been embraced; and what we see in Galatians 3:16 is another case of Paul’s “topsy-turvy” way of handling scriptures that logically excludes all Jews from being descended from Abraham in order to link Jesus mystically to his descent; and this “reasoning” opens the door to Romans 1:3 likewise pointing to a mystical relationship, especially since it is said there that the idea derives entirely from scriptural exegesis. We also know that the word for “betrayed” more exactly means “delivered up”.

Finally, we know Paul could use the unambiguous Greek word that meant “born” when he wanted to, but in Galatians 4:4 he used a word that is just as often translated “made” or “came about”, and it is used in a chapter that is riddled with allegories of women, various nonliteral mothers, children, tutors, adoptees, Jews and gentile believers.

But I did promise to hold off the questions till the end so let’s resume.

But I did say I’d come back to the passages in which Vermes sees Paul drawing on humanly transmitted teachings of Jesus.

The first passage is 1 Corinthians 15:3-7 in which he says that he taught what he had received. I have previously addressed our inability to place full confidence in this passage as being original to Paul. We also need to address the fact that in Galatians 1:11-12 Paul said he received his teaching by revelation from Jesus and not from men. And despite his apparent disclaimer otherwise in Galatians we also know that the gospel he taught to the Gentiles was not the same one taught by the Jewish Christians supposedly under the direction of James and Peter. It is Paul’s difference in teaching that is in fact the primary theme of Geza Verme’s chapters 3 and 4 in The Changing Faces of Jesus.

The second passage Vermes’ attributes to Paul’s reliance upon oral tradition is Romans 1:3-4. The preceding verse, verse 2, however, informs readers that Paul’s source for this message was scripture. So we touch on a debating point, here.

Another teaching Paul is said to have derived from oral transmission is Jesus’ teaching on divorce (Mark 10:11-12; Matthew 5:32 and 19:9). The passage is 1 Corinthians 7:10-12. I would have thought it a very thin thread tying the idea a woman was not to divorce her husband to an earthly Jesus. Was not this the common understanding of what “the Lord” had commanded from the beginning of time? Vermes then touches on something I think should be kept in mind whenever other related questions about Paul are raised: Paul’s cavalier ability to change even “the teaching of the Lord” according to his own spiritual understanding! (See verse 12 in the above linked passage.)

Now why would a person who had no qualms about adding to or subtracting from the very commands of God (and one who we have already seen repeatedly capable of turning the holy scriptures topsy turvy to conform them to his mystical vision) be particularly worried about being seen to have his teaching approved by “so-called pillars” (as he calls them in Galatians) or (sarcastically in 2 Corinthians) “super-apostles”?

But it gets “better” or “worse” according to one’s view. Vermes goes on to also say that it is “conceivable that Paul re-edited the traditional version” of an orally transmitted Last Supper ritual (p. 68). Further, Paul flatly contradicts Jesus’ own evaluation of the Torah:

So, contrary to the real Jesus who found in the Torah of God his supreme source of religious inspiration, Paul’s judgement of the Law is mostly critical. (p. 96)

So we have here a Paul who is not beyond changing the commands of God, playing topsy-turvy with scripture, but also conceivably capable of creatively re-writing and even contradicting the “oral traditions” he has presumably received from the authority of “oral transmission”!

But I said I was going to leave the questions to the end, and there is more that needs to be covered before returning to this question.

Another teaching Vermes attributes to Paul’s knowledge of oral tradition is 1 Corinthians 9:14. I have linked the chapter in full to show how strong the foundation of the claim is.

The final word-of-(human)mouth knowledge Paul had was the formula for the eucharist or Last Supper (1 Corinthians 11:20 ff.) Vermes acknowledges some difficulties here, however, and concludes:

In the case of the eucharist, however, his source is said to be Jesus, implying that it was directly revealed to him. ‘I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you’ (1 Cor. 11:23). . . . Consequently Paul’s wording may have been the primary source for the New Testament formulation of the establishment of the eucharist. In other words, there is a good chance that the eucharistic interpretation of the communal meal of the church was due to Paul, and that the editors of Mark, Matthew and especially Luke . . . introduced it into their respective accounts in the Synoptic Gospels. (p. 69, my bolding)

Conclusion: Vermes draws attention to the quantitatively slight evidence for the teachings of the historical Jesus in Paul; I have attempted here to further draw attention to its qualitative slightness as possibly derived via human tradition.

Paul’s creation: the mystical-mythical Jesus

So according to Geza Vermes Paul’s silences with respect to “the historical Jesus” are not the result of his letters being occasional writings. Vermes even observes, as noted above in relation to celibacy, that Paul harms his own arguments by what he believes is his deliberate avoidance of any reference to “the historical Jesus”.

Now Vermes’ motivational interpretation of Paul’s silence hangs entirely on the historicity of Jesus. Since apostleship was normally the privilege of those who had been with Jesus ever since the days of John the Baptist, and since apostles who claimed this privilege despised Paul as a “self-promoting upstart” who taught the wrong (anti-nomian) Gospel anyway (see above), it served Paul’s interests to base his apostleship upon the spiritual or heavenly Christ.

Harking back to anything to do with the “historical Jesus” would immediately undermine his position. He would be reminding his readers that the other apostles knew more about all of that side of Jesus than he did.

This is Geza Vermes’ argument.

This argument surely undermines those arguments that seek to find some clear pointers to a historical Jesus in Paul and strengthen the claims of those (not only mythicists) who dispute or question such “clear pointers”. One might even suggest that in some cases the argument for interpolation (some of which are referred to above) are strengthened by Vermes’ argument.

I am not at all suggesting that Vermes himself thinks this way. I am thinking through the logical consequences of his argument in the context of certain familiar responses by some historicists in their attempts to argue against mythicism.

But it must be remembered that Vermes’ argument hangs entirely upon the hypothesis that Christianity began with a historical Jesus who is somewhere hidden beneath the pages of the synoptic gospels. From this one constructs the scenario of oral transmission. But as I have hinted from time to time in the above “presentation” of Vermes’ argument, there is also room for alternate readings of several passages in Paul — and in the case of the eucharist Vermes is himself drawn to conclude that Paul either conceivably at least so creatively added to anything he may have learned from oral transmission that he effectively originated the ritual that later appeared in the Gospels, or that he had the demonstrated power to introduce a new teaching into the church entirely on the strength that it came to him by revelation.

Is not there an inconsistency here? Do we not see here evidence of a thinker who was paving his own creative way without caring seriously for what others — even other apostolic rivals and their followers — thought? He thrives on his differences from them. These enable him to boast of his superiority over them. Vermes and others certainly acknowledge Paul’s creativity. But they are too conservatively bound to institutional paradigms when they keep dropping in limiting caveats to his creativity.

Paul’s demonstrated (or strongly argued) creativity finally leaves us with no need to postulate any historical Jesus as the originator of Christianity. It was Paul’s theology that became the foundation of Christianity. All the rest was only filler. But that filler was important as ballast. Without it, Paul’s Christ could float in almost any direction

I think Vermes’ description of Paul’s “church meetings” supports my view here. I will come to that.

How creative was Paul when constructing his non-historical Jesus?

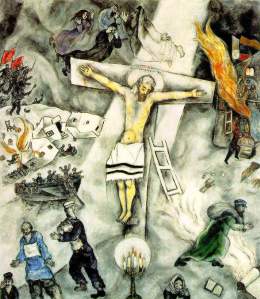

Of the “mystery of Christ’s death and resurrection” (Romans 8:34) Vermes declares:

Ultimately this amounts to a myth-drama of salvation. (p. 83)

What does Vermes mean by “myth”?

I do not use ‘myth’ in any pejorative sense, but as an interpretative concept entailing what is often a poetic explanation attached to death, burial, life, revival, etc. The Pauline myths understood in this sense do not depend on what Jesus taught or even on what he did, but on the consequences, assumed to be providential, of what happened to him. (p. 83)

Vermes’ use of the words “life” and “revival” following “death, burial” are interesting. Why not say “resurrection”? Would such a blunt word give the game away? That is, would it make it too clear that the subject of this poetic interpretation is itself really a “myth” in that pejorative sense, too? No doubt Vermes would disagree and say that “the resurrection” was the “mythical-poetic” explanation of the disciples’ subjective feeling of having Jesus with or in them after his death.

But Vermes does later concede that Paul’s own readers (and believing Christians today) think of the crucifixion as itself a ‘mythical’ event in the sense that its historical details are irrelevant. There is, in other words, no ‘mythical’ explanation of the historical details of Jesus’ death. After tracing the mystical drama God was working through Christ — one becoming a curse and dying for all to liberate all from death and a curse; coming in the likeness of sinful flesh to condemn sin in the flesh; as all die in the first Adam because they have inherited Adam’s sin, so all live in the second Adam etc etc etc . . . . — Vermes explains what they meant to their original (and modern-day believing) readers:

Perplexing though these statements may appear to detached or uninvolved readers, for believers who see them through the eyes of faith they are full of meaning. For them, the crucifixion of Christ is a ‘mythical’ event which needs no explanatory detail. Paul does not even specify by whom and for what reason Jesus was killed. (my bolding)

Paul’s central mental focus was on this ‘mythical’ (not historical) event. In 1 Corinthians 1:22 he said he wished to know nothing but Christ crucified. He repeated it in 2:2: “I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ and him crucified”. We know he was not thinking of mocking crowds as we read of in the Gospels, nor of two thieves either side, nor or Roman soldiers nearby. The event in Paul’s mind “needs no explanatory detail”. It is the fact of death itself — a death mystically covering the deaths of all humankind and through which all the faithful will be delivered from their own deaths — that is all he dwells upon. This is not a “historical event”. The event itself has become entirely “myth” in the mind of the believer.

The ‘myth’ is drawn in Paul’s mind not from historical events but from, as Vermes himself remind us, from the mythical tale of Abraham’s offering of Isaac.

[Paul] seems to have been more profoundly influenced by the story of the spiritual self-oblation of Isaac than the blood-shedding ceremonies of the Temple of Jerusalem. In his mystical vision, it is God-given faith that unites believers with the crucified Christ and allows them to appropriate for themselves the fruit of the cross. Such spiritual communion with the death of Jesus allegorically terminates sinful existence and opens the door to a new life. . . . (Rom. 6:6) (p. 87)

Vermes had earlier discussed this at length. I quote just a few words. Concerning the Jewish tradition of the effect of Isaac’s self-offering (Second Temple exegesis drew this conclusion that Isaac was knowingly offering himself):

Every future deliverance of the Jewish people and their final messianic salvation would be seen as resulting from the merit of the sacrificial event of the Akedah [Binding of Isaac]. Each time God recalled the Binding of Isaac, he would show mercy to his children. . . . Isaac’s willingness to be sacrificed was transformed in Jewish religious thought into a redeeming act of permanent validity for all his children until the arrival of the Messiah. (p. 85)

Earlier Vermes had shown that the author of the Gospel of John derived his imagery of the Lamb of God from

an ancient Aramaic interpretation of Exodus 1:15 according to which Pharaoh’s cruel decision to put to death all the male children born to the Jews in Egypt was inspired by a dream. In it he saw that a lamb, placed in one of the scales of a balance, outweighed the whole of Egypt lying in the other scale. The royal dream-interpreters explained to the king that a Jewish boy (Moses) about to be born would in due course destroy Egypt and liberate the Israelites. Hence the ‘Lamb of God’ typifies two saviours, Moses and Jesus. (p. 36)

So we have the essential myth of the sacrifice of the Saviour emerging from reflection on the myths of Isaac and Moses. Of course there is no need for “explanatory detail”. The myth is the mystically powerful death of the Saviour.

One stock response to mythicist arguments is that no Jew would ever have just made up the idea of a Davidic Messiah being crucified. That seems untenable especially in the light of the above sorts of interpretations that were known to exist at the time. Someone clearly did make up such an idea. The only question was whether it was creatively inspired by an attempt to hold on to a belief that one’s hero really was the coming David even though he had been crucified yet somehow he seemed to be “alive” in the hearts of his followers some time later, or whether it may have been inspired by passages in the Psalms of David that speak of that David’s being rejected by his own and at the point of death from his enemies, yet maintaining faith that he would in the end be delivered by God. But this is not a theme that Vermes addresses.

But Paul also acknowledged the need for some praxis, if only ritualistic. Baptism was the ritual by which believers entered symbolically or mystically into union with the death of that Saviour.

This all surely sounds like something out of a mystery religion. Vermes agrees:

By means of a simple yet highly expressive ritual, reinterpreted by Paul, this mystical union could turn into reality for each believer. This ritual was baptism as conceived by Paul, which echoed the Oriental mystery cults widespread in the Graeco-Roman world of that era. (p. 89)

This leads on to Paul’s creative symbolic life of Christ in the believer:

In addition to the immediate result of this mystical union with the risen Lord which Paul envisaged as a substitution of a life in God’s service ‘through Jesus Christ’ for a sinful existence, the symbolic baptismal resurrection also provided the neophyte . . . a ticket for participation in the final resurrection. (p. 90)

So for Paul Jesus works at an entirely symbolic (or mystical) level — whether in “death” or “life”.

This was not the gospel of the Jewish church and apostles according to Paul. It had no relevance to anything historical or orally transmitted. Vermes, believing in a historical Jesus, finds here a self-seeking motivation on Paul’s part. But such an interpretation runs into passages that appear to contradict that motivation — as discussed above. Recall, further, that we have a Paul here who — if he did know of anything Jesus said by means of oral tradition — was quite prepared to re-write those words or even contradict them.

Is there not a simpler explanation that needs no such motivational assessment of Paul alongside follow-up rationalizations of the details that contradict that assessment?

The evidence of Paul’s church meetings

Vermes’ description of what we know from Paul’s letters about church assemblies opens up other questions. We know what Paul’s rules were for headgear for women and men. It appears that each meeting included a “Lord’s Supper” — much as we find also in the Didache. Most interestingly, however, Vermes describes the meetings in contemporary terms as

a kind of cross . . . between a Pentecostal service and a Quaker meeting. (p. 99)

The two primary spiritual gifts Paul listed were those of prophecy and speaking in tongues. But there had also to be an interpreter of the tongues speaker. There was no sermon as such. No reading of scriptures, not even those of the Jewish bible.

So what did they prophesy or “gloss” about?

If, as Vermes argues, Paul was in constant need to defend himself and his churches from takeover by other apostles who had known the historical Jesus, and that this accounts for his deliberate shunning of the historical Jesus and his creation of a Jesus who embodied a mystical salvation myth in its place, then what were the sources of inspiration for these prophesying and tongues-speaking church-goers?

Let me hazard an entirely speculative guess. Their inspiration source was the mythical/mystical drama of salvation personified in the spiritual Christ itself.

I base this in part on Vermes’ own explanation of what Christ was for the believer during worship activities:

How, then, does this Christ fit into the worship of Paul’s churches? He is not the object of prayer . . . . Christ is rather the channel which carries the Christians’ supplications or thank-offerings to the Father; he is as it were the powerhouse of Pauline piety. (pp. 97-8)

Christ is the channel of communication or mediation between believer and God. That is what is meant by the believer having to do all things “in Christ”.

(Troels Engberg-Pedersen has argued likewise that for Paul Christ took on something of a similar sort of conceptual function for Christians as the Logos did for Stoics, although for Stoics Logos, of course, meant “Reason”. Logos was the channel or means by which the newly enlightened “rational” person was raised up to an identification with “Reason” and took on a new identity and place within a community of like-minded others. His whole self-identity and direction of life was changed through the agency of the Logos.)

One can imagine believers waxing eloquent of the wonders of their mystical union with God through Christ, and the drama of death and resurrection that they symbolically and vicariously experienced, etc.

But what happens to such a group when they hear that there are other Christians who are teaching about the details of how Jesus died and what he did and said before he died?

How could Paul possibly have founded churches of the kind he appears to have started with such a serious potentially undermining threat ever-present?

In other words, how can we explain the sorts of churches Paul founded so long there was any awareness at all of a teaching that Jesus had been not restricted to a mythical/mystical drama but had actually had a life in the flesh, too? Would they really all dutifully turn their backs on such apostles and brethren and refuse to listen to a word they said as Paul (according to Vermes) might have wished?

The only answer is that the concept of Christ he and his followers embraced was so divorced from any historical roots that the idea of a “historical Jesus” was as alien to them as an entirely different religion. And for this situation to ever have arisen in the first place, perhaps were was no such thing as a competing “religion” that taught salvation through faith in and obedience to a historical man who performed miracles to prove his Messiahship and taught a higher law as the way to eternal life and who was, after a martyr’s death, vindicated by being to the right hand of God.

Geza Vermes’ explanation for the success of Paul’s churches does not address this question:

Judged by the ordinary human wisdom the abstract and mystical-mythical theology of Paul combined with his ardent belief in the imminence of the return of Christ had only a very limited chance of succeeding, especially as it was addressed to a religiously unsophisticated Greek audience which, apart from a small number of better-off merchants and artisans, and the odd official like Eratus, the city treasurer of Corinth (Rom. 16:23), was largely recruited from the lower classes of society. Yet compared with the ultimately failed ministry of Peter, James and the other apostles among the Jews, Paul’s Gentile Christianity turned out to be a lasting success. The secret of this success lies, I believe, in the influence of the Pauline ‘myth’ seen as a spiritual liberation by Christ and as an equal treatment granted to the redeemed, whether great or humble, by their divine Father in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ. Though impervious to rational proof, Paul’s gospel made a greater impact than the Judaeo-Christian attempt at demonstrating from biblical exegesis that [the historical] Jesus was the Messiah promised to the people to the people of Israel. (pp. 103-4)

Expressions of gratitude and liberation and perhaps more mystical analogies would, I expect, have dominated the prophesying, prayers and tongues-speaking at the church gatherings around the sacramental meal. Spiritual liberation was probably a key to success as Vermes suggests. And that was achieved through Paul’s creative mystical myth of Christ crucified and salvation through the last Adam and mystical union with the death and resurrection of that Saviour. No need for explanatory detail. That would only detract from the power of the gospel myth.

But Vermes knows this sort of liberation could not sustain churches forever. The mystery cults of the ancient world did not last. There was another element that Vermes reminds us of and that was vitally important. Paul also taught the imminent coming of that Christ. Vermes speaks of “burning eschatological expectation”. (No-one spoke of a “second” coming.)

So what sustained the churches when that burned itself out? To explain this, says Vermes,

we have to admire the organizational talent and pastoral zeal of Paul and his companions. (p. 104)

This brings us into the Pastoral epistles which, we know, are not by Paul. But they do inform us of the organizational structure (bishops, deacons) that kept the church together after the eschatological zeal burned out.

But one must also question Vermes’ statement that Paul’s churches did “turn out to be a lasting success”. Those pastoral epistles bearing Paul’s name have lost the early sense of “spiritual liberation”.

Was there ever a church that, contemporary with Paul’s, “attempted to demonstrate from biblical exegesis that [the historical] Jesus was the Messiah promised to the people to the people of Israel”? That is surely the product of a later generation when the Gospels and Acts finally emerge on the scene. How could it have been otherwise given Paul’s ability to plant and/or water the sorts of churches he did throughout the Greek world?

Paul’s churches did not survive. They suffered schismatic histories that took them into clutches of the Pastoral autocrats, Valentinianism, Marcionism, Apelleanism, and many others, including something like a “proto-orthodoxy” that emerged in the wake of the composition of “Mark’s” parable-like, certainly richly symbolic, Gospel.

So alien were Paul’s churches, even his fundamental gospel teachings, that no-one in that trajectory leading to “Christian orthodoxy” breathed a word of them again until the latter second century by which time Paul himself was becoming catholicized.

The title of Vermes’ book is most apt:

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

VERMES

He was prepared to designate himself ‘the least of the apostles’ and in an off-guard moment to go as far as to declare that he was ‘unfit to be called an apostle’ (1 Cor. 15:9),

CARR

I wonder why Vermese deliberately chopped out Paul’s own explanation of why he was unfit to be called an apostle?

‘ For I am the least of the apostles and do not even deserve to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God.’

Verme’s thesis is that people would not think of Paul as an apostle because he had not seen Jesus, and so he has to hide Paul’s own explanation of his inferiority, because it does not fit Vermes’s thesis.

I overlooked that one. There are other times when Vermes misreads stuff, too. Like most others he can’t help but read gospels into Paul. So when he reads “buried” in 1 Cor. 15:4 he writes “Paul’s imagery presupposes a tomb” (p. 89). Maybe Paul is thinking of a tomb, but how can we be so sure? He also sprinkles many motivational adjectives throughout in some sort of attempt to enliven the action of gospel participants. Peter is “gutless” or without “guts”, for example. I can understand why he is doing this sort of thing but at the same time it inevitably tends to drags readers into his Gospel narrative world with him all the way even in his chapters on Paul.

Interesting stuff. I have read Verme’s translation of the Dead Sea Scrolls in english. Enjoyed it very much.

Cheers!

Contrary to popular opinion, and how much it gets repeated in arguments, an argument from silence is a legitimate form of evidence. It might be strong or weak evidence, but it’s evidence nonetheless. It depends on how much weight you would put on the evidence if it indeed was there.

If P(H) is 50%, then P(H | E) would be greater than 50%, depending on how much E is evidence for H. Necessarily, P(H | ~E) would have to be less than 50%, again, depending on how much E is evidence for H; P(H |E) + P(H | ~E) has to equal the initial P(H) – in this case 50%. If someone wants to assert that an argument from silence is fallacious, then they will have to show why probability theory is wrong or doesn’t apply.

J. Quinton: It depends on how much weight you would put on the evidence if it indeed was there.

It also depends on expectations of genre.

While I don’t agree with them, here is what I think mainstream scholars would say in the case of the epistles. The probability of finding something in a text depends greatly upon the genre and what you’re looking for. If you happened upon one of my old grocery shopping lists, your odds of finding my thoughts on Bebop and Baroque are effectively zero.

Wrong genre.

This is why they label all of Paul’s epistles “occasional letters,” ignoring the fact that Romans could easily be subtitled, “My Gospel Explained.” If they can get you to agree that Paul’s letters are responses to problems in churches that he started, then perhaps they can persuade you that Paul wouldn’t have any reason to talk about subjects such as Joseph and Mary, John the Baptist, Nazareth, etc.

Sounds reasonable so far.

However, setting Romans to one side, since it clearly shatters their argument, it still strains credulity to think that Paul would make pronouncements about Christian doctrine or standards of behavior and not quote Jesus or use an example from his life on Earth. So I think your analysis of the probability stands. We would reasonably expect that Paul would talk about the Jesus of history to bolster his points. Absence in this case is legitimate evidence and needs to be explained, not explained away.

Since there was no historical Jesus, the title “apostle” does not mean an original disciple of the historical Jesus. The title must have some other meaning.

The literal meaning is “someone who is sent out”. This literal meaning does not indicate that the person knew or followed Jesus or knew or followed anybody else.

Rather, the literal meaning indicates a decision was made by some authority that the person be sent on a trip. In other words, the person is authorized by some central authority to represent that authority in some distant location. So, other English words that could be attributed to an “apostle” would be “ambassador” or “delegate” or “representative”.

When Paul used this word “apostle” about himself, perhaps he used it falsely. Perhaps he had not been sent out by any authority, perhaps he was not authorized by any authority, perhaps he did not represent any authority.

I assume, however, that he was sent out by the Christian leadership, that he was authorized by the Christian leadership and that he did represent the Christian leadership. He disagreed about a few issues, most obviously circumcision, but in general his teachings did harmonize with the teachings of the Christian leadership.

Paul’s teachings might have been troublesome to the Christian leadership to some extent, but I assume that there were few capable volunteers for the traveling missionary work that Paul agreed to do for the Christian leadership.

I don’t see any problem in interpreting “apostle” as one who has been called and sent out *by God* or by the “spirit.” Those who “preach another Jesus” are also motivated by the spirit. Some scholars realize that Paul’s rivals condemned in 2 Cor. 11 are not the Jerusalem group or anyone connected to them; thus they are not “sent out” by some authorizing group such as the James & Co. pillars. They have taken up their apostleship because, like Paul, they have had some revelatory impulse which impels them onto the road. That’s what they all have in common, even Paul vs. the Jerusalem apostles: “Have I not seen our Lord?”

Vermes’ vast rationalization is not only unnecessary it is a fantasy without evidence.

I agree with everything you write here. I am disputing the idea that the title “apostle” belongs only to someone who personally had known a historical Jesus Christ.

Another English word that could be attributed to an “apostle” would be “missionary”.

Paul claimed that his knowledge was based on mystical visions, but all the original Christians claimed that their knowledge was based on mystical visions. They all climbed to the top of Mount Hermon and experienced a mystical vision. They all saw Jesus Christ, the son of God the Father, being crucified, dying, being buried, arising from the dead, and ascending into the heavens. This experience is the basis for the special knowledge that all the original Christians claimed to have.

The complication in the case of Paul was that he experienced his own mystical vision after James did so. James was supposed to be the last human being to experience the mystical vision.

Paul’s experience was too late. Paul’s mystical vision should not have been validated by the Christian leadership after James joined the leadership.

Not only was Paul’s experience too late, it did not happen with the preparation and guidance of the Christian leadership. According to Acts, it did not even happen on the summit of Mount Hermon, but rather in isolated circumstances during a road trip to Damascus.

Perhaps Paul’s mystical experience was validated nevertheless by the Christian leadership despite these various inadequacies. Or perhaps Paul was an impostor, whose mystical experience never was validated and who never was authorized to act and speak for the Christian leadership.

In my opinion, Paul’s experience was validated and he was authorized by the Christian leadership, but eventually he became troublesome for the leadership, because of his opinions about circumcision and other particular Judaizing issues.

In general, however, Paul was in harmony with the Christian leadership about the essential teaching that Christianity was based on a mystical vision of Jesus Christ’s crucifixion, death, burial, resurrection and ascension, which took place on the Firmament.

‘Harking back to anything to do with the “historical Jesus” would immediately undermine his position. He would be reminding his readers that the other apostles knew more about all of that side of Jesus than he did.’

So why was Paul accepted as an authority by the churches he was writing to?

Were the people he was writing to as dumb as a box of rocks, and listened to all this oral tradition about the life of Jesus and never twigged that Paul never appeared in stories about the life of Jesus?

So Paul thought he had better not remind his readers that all this oral tradition excluded him, because without constant reminders of the content of the oral tradition, his readers would simply forget who had been a disciple of Jesus and who had not?

This makes as much sense as Martin Luther King leading the Klu Klux Klan by the simple trick of never reminding them that he was black.

Steven asks:

“So why was Paul accepted as an authority by the churches he was writing to?”

Maybe it’s because he says that he worked harder: “Are they servants of Christ? I am a better one … with far greater labors” (2 Cor. 11:23).

It doesn’t look like it was easy: “For if someone comes and preaches another Jesus than the one we preached, or if you receive a different spirit from the one you received, or if you accept a different gospel from the one you accepted, you submit to it readily enough. I think that I am not the least inferior to these superlative apostles” (2 Cor. 11:4-5).

“I am astonished that you are so quickly diserting him who called you in the grace of Christ and turning to a different gospel” (Gal. 1:6).

“Before certain men came from James, [Cephas] ate with the Gentiles; but when they came he drew back and separated himself, fearing the circumcission party. And with him the rest of the Jews acted insincerely, so that even Barnabas was carried away with their insincerity … I saw that they were not staightforward about the truth of the gospel” (Gal. 2:12-14).

“O foolish Galatians! Who has bewitched you … Let me ask you only this: Did you receive the Spirit by works of the law, or by hearing with faith? Are you so foolish? Having begun with the Spirit, are you now ending with the flesh?” (Gal. 3:1-3).

But he was willing to make the effort: “To the Jews, I became as a Jew, in order to win Jews; to those under the law I became as one under the law -though not being myself under the law- that I might win those under the law. To those outside the law I became as one outside the law … To the weka I becamw weak, that I might win the weak. I became all things to all men, that I might by all means save some … I do not run aimlessly, I do not box as one beating the air” (1 Cor. 9:20-26).

I don’t imagine that James group was willing to do these things.

Effort might help win a race against others in the same race, but the problem with Paul’s view of Jesus — given that the “real Jesus” was more like something in the Gospels — is that Paul’s rivals are not in the same race at all. Once a child learns the truth about Santa Claus, that he was just a myth, there is no amount of effort by anyone that is going to convince him otherwise.