Gilad Atzmon recommends a number of books that address underlying causes of hostility against Jews. One is The Jewish Century by Yuri Slezkine. Of Slezkine’s theory of ethnic identity the Wikipedia article explains:

Slezkine characterizes the Jews (alongside such groups as the Armenians, overseas Chinese, and Gypsies) as a Mercurian people “specializ[ing] exclusively in providing services to the surrounding food-producing societies,” which he characterizes as Apollonian. With the exception of the Gypsies, these “Mercurian peoples” have all enjoyed great economic success relative to the average among their hosts, and have all, without exception, attracted hostility and resentment. Slezkine develops this thesis by arguing that the Jews, the most successful of these Mercurian peoples, have increasingly influenced the course and nature of Western societies, particularly during the early and middle periods of Soviet Communism.

My gut reaction to reading a theory dividing people into Mercurians and Apollonians was that this is surely rubbishy oversimplification. But then I read a sample of the book . . . .

Mercurians

Mercurians

The publisher of this book makes a key sample chapter available online and I find the concepts most interesting. It appears that Slezkine has been able to understand anti-semitism much more broadly than any thesis that seeks biology or religion as an explanation. I have bolded some of the key sections for easier skimming.

There was nothing particularly unusual about the social and economic position of the Jews in medieval and early modern Europe. Many agrarian and pastoral societies contained groups of permanent strangers who performed tasks that the natives were unable or unwilling to perform. Death, trade, magic, wilderness, money, disease, and internal violence were often handled by people who claimed–or were assigned to–different gods, tongues, and origins. . . . .

All these groups were nonprimary producers specializing in the delivery of goods and services to the surrounding agricultural or pastoral populations. Their principal resource base was human, not natural, and their expertise was in “foreign” affairs. They were the descendants–or predecessors–of Hermes (Mercury), the god of all those who did not herd animals, till the soil, or live by the sword; the patron of rule breakers, border crossers, and go-betweens; the protector of people who lived by their wit, craft, and art.

Most traditional pantheons had trickster gods analogous to Hermes, and most societies had members (guilds or tribes) who looked to them for sanction and assistance. . . . .

Hermes’ protégés communicated with spirits and strangers as magicians, morticians, merchants, messengers, sacrificers, healers, seers, minstrels, craftsmen, interpreters, and guides–all closely related activities, as sorcerers were heralds, heralds were sorcerers, and artisans were artful artificers, as were traders, who were also sorcerers and heralds. They were admired but also feared and despised by their food-producing and food-plundering (aristocratic) hosts both on and off Mount Olympus. Whatever they brought from abroad could be marvelous, but it was always dangerous . . . . .

The asymmetry goes much further, of course. The host societies have numbers, weapons, and warrior values, and sometimes the state, on their side. Economically, too, they are generally self-sufficient–not as comfortably as Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain may have believed, but incomparably more so than the service nomads, who are fully dependent on their customers for survival. Finally, beyond the basic fear of pollution, the actual views that the two parties hold of each other are very different. In fact, they tend to be complementary, mutually reinforcing opposites making up the totality of the universe: insider-outsider, settled-nomadic, body-mind, masculine-feminine, steady-mercurial. Over time, the relative value of particular elements may change, but the oppositions themselves tend to remain the same (Hermes possessed most of the qualities that the Gypsies, Jews, and Overseas Chinese would be both loathed and admired for). . . . .

European anti-Semitism is often explained in connection with the Jewish origins of Christianity and the subsequent casting of unconverted Jews in the role of deicides (as the mob’s cry, “his blood be on us, and on our children,” was reinterpreted in “ethnic” terms). This is true in more ways than one (the arrival of the Christian millennium is, in fact, tied to the end of Jewish wanderings), but it is also true that before the rise of commercial capitalism, when Hermes became the supreme deity and certain kinds of service nomadism became fashionable or even compulsory, Mercurian life was universally seen–by the service nomads themselves, as well as by their hosts–as divine punishment for an original transgression. One “griot” group living among the Malinke was “condemned to eternal wandering” because their ancestor, Sourakhata, had attempted to kill the Prophet Muhammad. The Inadan were cursed for selling a strand of the Prophet Muhammad’s hair to some passing Arab caravan traders. The Waata (in East Africa) had to depend on the Boran for food because their ancestor had been late to the first postcreation meeting, at which the Sky-God was distributing livestock. The Sheikh Mohammadi say that their ancestor’s sons behaved badly, “so he cursed them all and said, ‘May you never be together!’ So they scattered and went on scattering in many places.” . . . . .

Another common host stereotype of the Mercurians is that they are devious, acquisitive, greedy, crafty, pushy, and crude. This, too, is a statement of fact, in the sense that, for peasants, pastoralists, princes, and priests, any trader, moneylender, or artisan is in perpetual and deliberate violation of most norms of decency and decorum (especially if he happens to be a babbling infidel without a home or reputable ancestors). . . . .

Mercurians owe their survival to their sense of superiority, and when it comes to generalizations based on mutual perceptions, that superiority is seen to reside in the intellect. Jacob was too smart for the hairy Esau, and Hermes outwitted Apollo and amused Zeus when he was a day old (one wonders what he would have done to the drunk Dionysus). Both stories–and many more like them–are told by the tricksters’ descendants. . . . .

The Pity of it All

The second book recommended by Gilad Atzmon is The Pity of it All by Amos Elan. The Independent review and the Guardian review outline a tragic tale of Jews seeking to assimilate but with too much success, and too much economic success, with the result that when things went into tailspin for the nonJews they still were singled out for scapegoating. This reminds me of Niall Ferguson’s The War of the World: History’s Age of Hatred where I learned that the worst atrocities in Europe were cruelly heralded by an age of unprecedented outward respect and tolerance. The message was that the latter was responsible for a simmering unease among too many and it was only a matter of time before the simmering boiled over into violence.

The Link between Jewish Chauvinism and Anti-Semitism

The third book listed is Jewish History, Jewish Religion by Israel Shahak. In this book one reads of views espoused strongly by Gilad Atzmon himself in many of his writings. Much of the anti-semitism in both the Arab and Moslem worlds, including the openly declared motivations of anti Western (particularly anti-American) terrorists, has to do with the nature of the state of Israel and Zionism today. From the Wikipedia, and again with my own bolding:

The third book listed is Jewish History, Jewish Religion by Israel Shahak. In this book one reads of views espoused strongly by Gilad Atzmon himself in many of his writings. Much of the anti-semitism in both the Arab and Moslem worlds, including the openly declared motivations of anti Western (particularly anti-American) terrorists, has to do with the nature of the state of Israel and Zionism today. From the Wikipedia, and again with my own bolding:

In 1994, Shahak published Jewish History, Jewish Religion: The Weight Of Three Thousand Years. In it he proposes that most nations’ histories are initially ethnocentric. However they then evolve through a period of critical self-analysis to incorporate other perspectives. Jewish emancipation by the Enlightenment was a dual liberation, from both Christian anti-Semitism and a ‘ghetto priesthood’ with its ‘imposed scriptural control’. But, he argued, the history of Judaism itself had not yet been the full beneficiary of modern critical perspectives. For Shahak, open public discussion of what he called ‘Jewish ideology’ is required if people are to take the same attitude towards Jewish chauvinism as is commonly taken towards anti-Semitism and all other forms of xenophobia, chauvinism and racism. He believed the political influence of Jewish chauvinism and religious fanaticism was much greater than that of anti-Semitism, and affirmed his belief that anti-Semitism and Jewish chauvinism could only be fought simultaneously.

According to Shahak Talmudic Judaism is a totalitarian religion where rabbinical law governs every aspect of Jewish behaviour. Shahak’s approach to the subject draws on both Karl Popper’s concept of a closed society, his analysis of totalitarian thought-patterns in Plato’s thought, and also on Moses Hadas’s suggestion of a Platonic influence on rabbinical thought. He asserts that what he views as Jewish chauvinism and religious fanaticism are grounded in this theological tradition. For Shahak, the religious roots of this ‘Jewish ideology’ had two important consequences:

- Attempts by Western analysts to explain contemporary Israeli politics in purely secular terms such as imperialism are fundamentally flawed.

- More controversially, that ‘Jewish chauvinism’ can be a causal factor in antisemitism, and that both must be fought simultaneously.

This naturally raises the question of non-religious Zionists, but I cannot comment on Shahak’s explanation of this since I have yet to read his book. My own initial response would be that even among non-religious Jews it is religion and Zionist ideology that does define the identity of many in much the same way as Christian heritage and imperialism defined many non-practicing Christians in nineteenth century English speaking nations.

But Israel, Zionism and the Palestinian condition constitute the defining geopolitical crisis of our time.

Shahak also claims that Zionism is an attempt to re-establish a closed Jewish community and that this has resulted in discrimination against non-Jews. He also argued that on several occasions Zionists held links with anti-Semites, as was the case of Herzl and Count von Plehve, the antisemitic minister of Tsar Nicholas II; Jabotinsky and the Ukrainian leader Petlyura, whose forces, Shahak says, massacred some 100,000 Jews in 1918-21; Ben-Gurion and the French extreme right, which included notorious antisemites, during the Algerian war; and others such as the Zionist rabbi Joachim Prinz, who welcomed Hitler’s rise to power, since they shared his belief in the primacy of ‘race’ and his hostility to the assimilation of Jews among ‘Aryans’. Shahak notes that Prinz, whose book Wir Juden (We Jews, 1934) celebrating Hitler’s German Revolution and its defeat of liberalism, subsequently emigrated to the USA, where he rose to be vice-chairman of the World Jewish Congress and a leading light in the World Zionist Organization.’ He concludes by arguing the struggle against what he views as Jewish chauvinism and exclusivism, which must include a critique of classical Judaism, was of equal or greater importance as the struggle against antisemitism, and all other forms of racism.

The work was praised by Gore Vidal and Edward Said, both of whom wrote introductions to the book at various times. Robert Fisk wrote that his ‘examination of Jewish religious fundamentalism’ was “invaluable”:

[Shahak] concludes that “there can no longer be any doubt that the most horrifying acts of oppression in the West Bank are motivated by Jewish religious fanaticism.” He quotes from an official exhortation to religious Jewish soldiers about Gentiles, published by the Israeli army’s Central Region Command in which the chief chaplain writes: “When our forces come across civilians during a war or in hot pursuit or a raid, so long as there is no certainty that those civilians are incapable of harming our forces, then according to the Halakhah (the legal system of classical Judaism) they may and even should be killed … In no circumstances should an Arab be trusted, even if he makes an impression of being civilised … In war, when our forces storm the enemy, they are allowed and even enjoined by the Halakhah to kill even good civilians, that is, civilians who are ostensibly good.”

Gilad Atzmon: And What About Jewish Anti Gentile Studies

Article originally appeared on Gilad Atzmon (http://www.gilad.co.uk/).

Tuesday, June 28, 2011 at 3:19PM

http://www.gilad.co.uk/writings/gilad-atzmon-and-what-about-jewish-anti-gentile-studies.html

American Jewry won a victory last week: Yale University bowed to pressure – it is now starting yet another initiative to study anti-Semitism, after a decision to cancel an earlier programme had sparked criticism.

The earlier programme created in 2006 was cancelled because it had produced “little scholarly work,” and the institute’s courses had not attracted large numbers of students, according to Donald Green, the director of Yale’s Institution for Social and Policy Studies.

Abe Foxman of The Anti-Defamation League criticised Yale for cancelling the programme and welcomed the new initiative, saying “We are satisfied that Yale University understood the critical importance of continuing an institute for the study and research of anti-Semitism”.

The new programme will be led by Yale professor Maurice Samuels, who states that Yale has some of the leading scholars in the world working on anti-Semitism and interfaith relations. He intends to focus on contemporary and historical anti-Semitism.

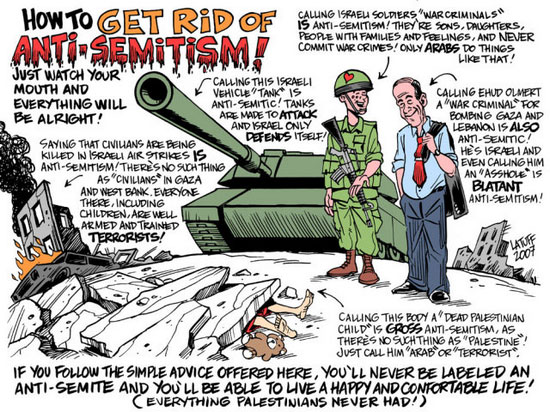

However, for all Yale’s efforts, I remain convinced that Samuels will not be able to produce any valuable scholarly work either – the reason is simple: almost the entire body of research on ‘anti Semitism ’ conducted in recent decades is solely concerned and obsessed with recording the historical points at which hatred of the Jews manifests itself. And yet, for some bizarre reason, such scholarly work on anti Semitism never seeks to understand, and is totally impervious to the socio-economic, the ideological, theological and historical contexts, motivations, causes and reasoning that have existed behind such outbursts of hatred against the Jews.

These countless studies on anti Semitism rarely look into the causes, and rarely try to understand why anti Semitism arose in so many places throughout history.

Instead of elaborating on the causes that may lead to anti Semitism, the discourse on anti Semitism is a unique chronological account that only ‘starts to tick’ as soon as an ‘anti Semitic’ event is detected. Everything prior to that is a blank slate – and so we are left, once more, none the wiser as to why people ‘turned against the Jews’ yet again.

I’d like to suggest here, that for an academic study of anti Semitism to be scholarly and comprehensive, and if we are to even begin to understand the roots of anti Semitism, then primary attention must surely also be dedicated to the considerable body of anti-gentile views expressed within the Torah, Talmud, and within contemporary Jewish ideology and politics (Zionist and Jewish anti-Zionist alike).

The institute’s scholars would also be well advised to elaborate on Jewish cultural supremacy, and Jewish political lobbying, from Purim to AIPAC.

For a study of anti Semitism to become scholarly and valuable, instead of merely a form of hyper-emotional hysterical ranting, the researcher would also be advised to first assume that, perhaps, anti Jewish feelings might well have root causes which could be rational, and could be explained and understood — yet not justified — in terms of causality and reason.

Instead of assuming that the Goyim are just a bunch of crazy blood thirsty lunatics that periodically just went mad again and again throughout history in their dislike for Jews, the scholars would rather be advised to look for the root causes that may well have lead to an anti Semitic event, ideology or text.

Such a study then, would surely be academically and socially valuable, and I believe it would also be crucial for Jews and Israelis, so they may be enabled to understand the world they live in, and to grasp their role in it.

Some commendable studies by Jewish academics have already been done in that area : The Jewish Century by Yuri Slezkine, The Pity Of It All by Amos Elon and Jewish History, Jewish Religion by Israel Shahak and even early Zionist texts by Max Nordau, Ber Borochov and others all provide some adequate answers to questions regarding the origins of anti Semitism. Interestingly enough, none of the above studies were produced or sponsored by ‘anti-Semitism research institutions’ . The above scholars attempted to grasp the origins of animosity towards the Jews, instead of looking for a symposium in which they could moan about being hated. The three former at least, were driven by genuine intellectual curiosity rather than by a need for collective therapy.

“Like many, I am concerned by the recent upsurge in violence against Jews around the world and I plan to address these concerns,” said Samuels the head of the new Yale Anti Semitism research centre.

Might I suggest that Samuel should be far more concerned with the upsurge in violence that is committed by the Jewish State in the name of the Jewish people. Samuels should look into the role of AIPAC in shaping American and world affairs.

Will Samuels be courageous enough to do so? I do not know Samuels, but somehow, I find it hard to imagine.

Article originally appeared on Gilad Atzmon (http://www.gilad.co.uk/).

See website for complete article licensing information.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

JW:

I have faith that if you add up the numbers more Jews have been murdered by Christians and Muslims in the last 2,000 years than have died by natural causes. So be sure and look at the reverse argument as a good scholar should always do. Is whatever you think “The Jews” are guilty of a REACTION to what the Christians and Muslims did to them. Another interesting analogy, again required by good scholarship, is to consider what the Palestinians may be guilty of in Understanding the Reasons for Anti-Palestinianism.

Joseph

So how do you explain antii-semitism among both Christian and Moslem AND non-Christian and non-Moslem peoples throughout history? If you believe racism against comparable socio-economic groups is not comparable to anti-semitism, how do you identify, describe and explain this apparent uniqueness qualitatively?

“[Sharak] believed the political influence of Jewish chauvinism and religious fanaticism was much greater than that of anti-Semitism…”

I am not familiar with the book by Israel Shahak, but from what you are writing he seems to fall into the same category as Kevin B. MacDonald, who exposed himself to massive criticism by introducing the term “reactive anti-Semitism.” (By the way, MacDonald responded enthusiastically to Slezkine’s book, to which you are also referring.) MacDonald has probably gone too far; and I am not defending him. Racists have already turned him into an icon. Nevertheless, his chapter on the late Roman Empire keeps fascinating me. I believe he is correct in arguing that the writings of such Christian authors as John Chrysostom led to “an increasing identification of Christians as members of a group for whose members anti-Semitism was an important aspect of personal identity.” I wish other scholars would enter into dialogue with MacDonald on this particular subject.

I don’t know MacDonald’s work, but in preparing my post I came across some anti-Semitic sites using Shahak’s work to justify their hatred. I avoided them and declined to make use of them even when they made a large section of his writings available online.

The stubborn reality is that nothing will ever change for any people who refuse to embrace and learn from self analysis and understanding.