Some scholars (e.g. S.G.F. Brandon) have opined that Jesus was something of a revolutionary or rebel leader; others (e.g. Thomas L. Thompson) that he was “a messiah myth” (the link is to an earlier post of mine listing the mythical traits of gods and kings of the Middle East).

Some scholars (e.g. S.G.F. Brandon) have opined that Jesus was something of a revolutionary or rebel leader; others (e.g. Thomas L. Thompson) that he was “a messiah myth” (the link is to an earlier post of mine listing the mythical traits of gods and kings of the Middle East).

Other scholars (e.g. Robert M. Price) have compared the Gospel narrative elements of Jesus against the various functional components of folk tales as extracted by Vladimir Propp.

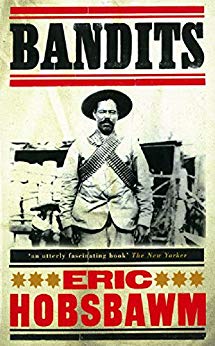

One nonbiblical historian who, to my knowledge, has never written a word about Jesus, has written about a certain type of rebel leader, however, and compared the realities with the myth or legend that has universally attached itself to these sorts of people. Eric Hobsbawm has researched the phenomenon of social banditry (from China through Europe to Peru), or the Robin Hood types of figures. His list of characteristics of the “noble image” that attaches itself to these figures is interesting.

It bears a striking resemblance to the qualities of the kings and gods of Thompson’s messiah myth traits as much as to the heroic human outlaw. If the same qualities attach themselves to both the human outcast and a mighty god or king of another, much earlier, era, then one is entitled to suspect we are looking at some deeper psychological need/attraction at work here.

Here’s Hobsbawm’s list of characteristics (p. 47f of Bandits, 2000).

First, the noble robber begins his career of outlawry not by crime, but as the victim of injustice, or through being persecuted by the authorities for some act which they, but not the custom of the people, consider as criminal.

Jesus becomes the hero truly understood and followed for who he really is after his unjust crucifixion. But he is also persecuted before this, early on in Mark’s narrative, from the moment he heals a withered hand on the sabbath. The figures of David and other Middle Eastern kings are also cast out or rejected for some unjust reason early in their lives, and must return to claim their rightful place. As for gods, they are sometimes attacked by evil forces, or at least are motivated to act on behalf of injustice done to their worshipers: see the second point.

Second, he ‘rights wrongs’.

Third, he ‘takes from the rich to give to the poor’.

Gods — including the God and Jesus of Luke’s gospel — are said to overturn the status quo by laying low the rich and powerful and lifting up the lowly and poor to exalted status.

Fourth, he ‘never kills but in self-defence or just revenge’.

I wrote something about “killer-saints” in an earlier post. Jesus doesn’t do that in this life, but he does leave a message that he will be back to kill his enemies “justly” in the future.

Fifth, if he survives, he returns to his people as an honourable citizen and member of the community. Indeed, he never actually leaves the community.

Jesus is said to always be with his followers, of course.

Sixth, he is admired, helped and supported by his people.

Of course the “people of Jesus” are really those who obey him, not those who are related to him genetically, as the gospels of Mark and John make clear.

Seventh, he dies invariably and only through treason, since no decent member of the community would help the authorities against him.

So it would seem that once Jesus was given a human biography a Judas had to be invented, too.

Eighth, he is — at least in theory — invisible and invulnerable.

This is where gods and outlaws meet, each in their respective ways.

Ninth, he is not the enemy of the king or emperor, who is the fount of justice, but only of the local gentry, clergy or other oppressors.

One could substitute chief god/God here for “king or emperor” in the case of Marduk, Jesus, et al. One might also consider the Gospel authors’ interest in blaming the priests (and Jewish king Herod) for the plots against Jesus, and seeking to exonerate the Roman powers, maybe?

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!