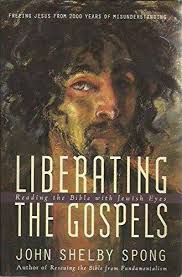

Some people might be disturbed at the suggestion that Jesus did not exist, but surely all good people would be happily hopeful were they to hear an argument that very symbol of anti-Semitism has been nothing more substantial than an unhappy fiction. After reading Bishop John Shelby Spong’s Liberating the Gospels: Reading the Bible with Jewish Eyes some years ago I was naive enough to conclude that most biblical scholars (of the nonfundamentalist variety) were well aware of the evidence that Judas was nothing more than a literary creation. I would still like to think that is the case, and that those scholarly works that speak of Judas as a real person of history who in fact did betray his master really are an aberrant minority in the current field of Gospel scholarship.

Don’t misunderstand, though. By no means does John Shelby Spong deny the historicity of Jesus.

Is there then no literal history that is reflected at the heart of the Christian story? Yes, of course there is; but it is not found in the narrative descriptions of Jesus’ last days. (p. 258)

But who was Judas?

- Was he a person of history who did all of the things attributed to him? . . .

- Or was there but a bare germ of truth in the Judas story, on which was heaped the dramatic portrait that we now find in the Gospels? Can we identify the midrashic tradition at work in the various details that now adorn his life? . . .

- Or was he purely and simply a legendary figure invented by the Christians as a way to place on the backs of the Jewish people the blame for the death of Jesus?

(p. 259, my formatting)

The rest of the post follows Spong’s argument that Judas was created by “Christians [who] made Jews, rather than the Romans, the villains of their story. [Spong] suggest[s] that this was achieved primarily by creating a narrative of a Jewish traitor according to the midrashic tradition out of the bits and pieces of the sacred scriptures and by giving that traitor the name Judas, the very name of the nation of the Jews.” (p. 276)

It may be possible to quibble over Spong’s use of the term “midrash”, which some scholars define as something that is known among the Dead Sea Scrolls but not quite found in the Gospels. But regardless of the term used, the identification of the details of the Judas narrative in the Hebrew Scriptures remains a telling argument that Judas was a literary creation of the Gospel authors.

The post is in two parts. The first part here outlines the main argument for Judas being a late fictional creation and reflecting a mounting anti-semitism within the Church. The second part looks in more detail at the inconsistencies with which the different Gospels present the Judas narrative.

The Meaning of “Iscariot”

It has been suggested that Iscariot refers to Kerioth, a town presumably of Judas’s origin.

But Spong writes that “today [published 1996] the weight of scholarship leans toward the [option that the name derives from sicarious, which means a political assassin].” (p. 259)

The Earliest Christian Reference to Betrayal

This is found in a letter of Paul usually dated to around the mid 50s.

I Corinthians 11:23

I received from the Lord that which I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the same night when he was betrayed took bread.

No name is associated with the betrayal. No hint that one of the twelve might have been responsible.

That is all the Christian Church had in writing about the betrayal until the seventh decade. (p. 260)

Inconsistencies in the Gospel Portraits of Judas

The first fact that must be registered is that the Gospels do not paint a consistent portrait of the man called Judas. Even if he were a literal figure of history, there is little agreement about the details of his life. (p. 266)

Judas betrayed Jesus

- in Gethsemane (Mark, Matthew)

- at the Mount of Olives (Luke)

- in a garden (John)

Judas came to arrest Jesus with

- a crowd from the chief priests, scribes and elders (Mark)

- a large crowd from the chief priests and elders of the people (Matthew)

- a crowd (Luke)

- a detachment of Roman soldiers accompanied by police from the chief priests and Pharisees (John)

Did the Sanhedrin assemble that night to condemn Jesus?

- Yes (Mark)

- Yes (Matthew)

- Yes (Luke)

- No (John)

Did Judas repent?

- — (Mark)

- Yes (Matthew)

- No (Luke)

- — (John)

How did Judas die?

- — (Mark)

- Hanged himself (Matthew)

- Fell down headlong and his bowels gushed out (Luke)

- — (John)

Judas, Constructed from the Hebrew Scriptures

What’s in a name?

Judas was the Greek spelling of Judah. Judah was the patriarch who founded the tribe of Judah, from which was named the Kingdom of Judah, later Judea. “Jew” originally meant a member of the nation of Judah.

In the midrashic tradition, when the traitor was given the name of the nation that, by the time the Gospels were being composed, was perceived to be the enemy of the Christian movement, then our suspicions that something more than history is at work out to be aroused. (p. 267)

From Joseph’s story, the name of Judas for the betrayer, and the ‘handing over’ for money

The Greek word for ‘betrayal’ literally means ‘to hand over’, “especially to hand over to a recognized enemy.”

Genesis 37-50 contains the famous story of Joseph.

- Joseph was “handed over” to an enemy by a group who became the leaders of the twelve tribes of Israel.

- The handing over of Jesus came from out of a group of twelve who became the leaders of the Church that came to call itself the new Israel.

- Joseph was handed over to gentiles, and death the presumed outcome

- Jesus was handed over to gentiles, with death the presumed outcome.

- God intervened to deliver Joseph from the hands of the gentiles

- God intervened to deliver Jesus from the fate administered by the gentiles

- Joseph had been momentarily imprisoned in Pharaoh’s jail

- Jesus had been temporarily buried in Joseph’s tomb

- 20 pieces of silver was the price of Joseph

- 30 pieces of silver the price of Jesus

- One of the twelve who urged that money be sought for Joseph was Judah

- It was Judas who sought money for the act of betraying Jesus

In the light of these similarities, it is hard not to doubt that there was some intermingling of the stories. (p. 267)

From the Book of Zechariah, betrayal of a shepherd king with 30 pieces of silver

And the LORD said unto me, Cast it unto the potter: a goodly price that I was prised at of them. And I took the thirty pieces of silver, and cast them to the potter in the house of the LORD.

Here Zechariah speaks of the betrayal of a shepherd king of the Jews for thirty pieces of silver. This silver was later hurled back into the Temple.

Matthew’s Gospel takes from this passage in Zechariah both the details of the amount of silver for which Jesus (a shepherd-king-to-be) and the throwing of it back into the Temple when Judas repented.

From Ahithophel, the story of the betrayer going out and hanging himself

King David was called an anointed one (=”messiah”), and he also was betrayed by a close confidante, Ahithophel. Ahithophel joined with those who had rebelled against David, but when he saw that their cause was lost he went and hanged himself. (2 Samuel 17:23).

“Christ” is the Greek for “messiah” or “anointed one”.

So later Jewish Christians reading this ancient tale would note that when Ahithophel betrayed the Lord’s anointed, he went and hanged himself (2 Samuel 17:1-23). It begins to sound very much like the Judas story. (p. 268)

The Masada suicides still fresh in the mind of Matthew?

The Jewish war did not end with the destruction of Jerusalem but with the reported mass suicide of Jews at Masada a few years later.

By the time Matthew wrote his gospel, the Jewish Christians had already begun to suggest that the destruction of Jerusalem was God’s punishment on the strict Jerusalem Jews for their refusal to accept Jesus as the Christ. Jesus, they argued, had been betrayed by his own people. . . . That betrayal, these Jewish Christians were asserting, had now resulted in the suicide deaths of the last remnants of the Jerusalem Jews in the Roman war. How easy it would be to interpret that Jewish behavior as betrayal, and together with its tragic suicidal results, relate this action directly to the life of Judas. This would be especially so if the traitor could be seen as a personification of the Jerusalem Jews. (pp. 268-9, my emphasis)

From Psalm 41, the story of a friend who become an enemy at a meal table

The Gospel of John identified the Psalm that was the inspiration for the scene of Judas participating in a meal with Jesus at the moment of his betrayal:

I speak not of you all: I know whom I have chosen: but that the scripture may be fulfilled, He that eateth bread with me hath lifted up his heel against me. . . .

He then lying on Jesus’ breast saith unto him, Lord, who is it?

Jesus answered, He it is, to whom I shall give a sop, when I have dipped it. And when he had dipped the sop, he gave it to Judas Iscariot, the son of Simon. (John 13:18, 25, 26)

The scripture that Judas fulfils is Psalm 41:9

Yea, mine own familiar friend, in whom I trusted, which did eat of my bread, hath lifted up his heel against me.

This narrative detail, explicitly associated with the Psalms, is also found in Mark 14:20, Matthew 26:23 and Luke 22:21. All three identify the traitor solely by his sharing a meal with Jesus. His name is not mentioned, but his sharing a meal with the one he betrays is singled out.

Thus even this detail from the Judas story also appears to have been the creation of a midrash tradition. It is of particular note to recognize that this psalm was originally thought of as a psalm of David bemoaning the betrayal of Ahithophel. These themes echo over and over again in the developing Judas tradition. (p. 269)

From Joab, the story of a betrayal with a kiss, and death by disembowelment

The three synoptic gospels tell of Judas betraying Jesus with a kiss when he met him in Gethsemane: Mark 14:44-45; Matthew 26:48-50; Luke 22:47-48.

This may be traced to another betrayal story in the Old Testament. The same story might also be the source of Luke’s account in Acts of Judas’s death with his bowels gushing out. (See the full quotations in the second half of this post.)

In 2 Samuel 20:1-10 David had replaced Joab with Amasa as captain of his army. Joab “rectified” this situation by approaching Amasa in friendship, with a kiss, in order to get close enough to stab him. The one strike spilled Amasa’s bowels to the ground, a detail that appears to prefigure Luke’s account of the death of Judas.

And Joab said to Amasa, Art thou in health, my brother? And Joab took Amasa by the beard with the right hand to kiss him.

But Amasa took no heed to the sword that was in Joab’s hand: so he smote him therewith in the fifth rib, and shed out his bowels to the ground, and struck him not again; and he died. (2 Samuel 20:9-10)

Spong does not mention the betrayal of David by his son Absalom. It might be worth noting that David himself kissed Absalom on his restoration to his father’s good graces after killing his brother (2 Sam. 14:33). The reader knows, however, that despite the kiss of welcome that Absalom is about to betray his father. Soon afterwards Absalom hatches his treachery by winning for himself the affection of David’s subjects through greeting with a kiss each one who sought his help (2 Sam. 15:5).

The sum of the above

That accounts for almost every detail in the gospel tradition regarding one known as Judas and called Iscariot. This analysis, at the very least, makes the midrashic creation of the Judas story sound more and more probable. At the very least, it suggests that most of the details about the life of Judas may not be literal at all. (p. 270)

The Inappropriate, Confused Context of the Judas Narrative

In John’s Gospel when in front of all the disciples Jesus identifies Judas as the one who is to betray him, the disciples respond bizarrely. Judas left after Jesus gave him the bread and told him to do “the dirty deed” quickly. But the rest of the disciples remain silent and allow all this to happen. There is no attempt to stop Judas.

In Luke , after Jesus announces that the one who is to betray him is at the table with them all, the disciples soon move on to a discussion about which one of them should be the greatest in the kingdom:

But the hand of him who is going to betray me is with mine on the table. The Son of Man will go as it has been decreed. But woe to that man who betrays him!” They began to question among themselves which of them it might be who would do this. A dispute also arose among them as to which of them was considered to be greatest. (Luke 22:21-24)

Other examples of the ill-fitting nature of the Judas narrative in the Gospels are given below in the comparisons of the different Gospel accounts.

Everywhere one looks, one discovers an inappropriate, confused context for the Judas narrative in the biblical tradition — which is exactly what one might expect to occur if a late-developing tradition ike the story of Judas had been superimposed onto an ancient account where it did not originally exist. From many angles the story of Judas appears to be a late-developing Christian legend. When we confront the results of our study — which reveal that all of the biblical details of Judas’ life appear to have been shaped by the Hebrew scriptures and therefore can hardly be regarded as literal and that the Judas story does not fit into the narrative of Jesus’ passion as an original part of the story might be expected to do — then we ask with renewed urgency whether Judas himself could still be thought of as a literal figure of history. (p. 271, my bold)

Why the Rush to Exonerate the Romans?

The only people who could have been responsible for the death of Jesus by crucifixion were the Romans. If the Jews condemned one to death the penalty would have been carried out by stoning. Yet the Gospels all attempt to shift the blame for the crucifixion on the Jews and portray the Roman governor, Pilate, as an unwilling party who attempted to free Jesus.

Pilate is said to have repeatedly attempted to release a murderous rebel, Barabbas. It is significant that Barabbas means literally “Son of the Father or God” (Bar=Son; Abba=Father or God). Pilate attempts to release one called “the Son of God” but the Jewish mob denies him. Since there was no known custom of Romans releasing a prisoner on a Jewish holy day, there is every reason to think that Barabbas has been invented to paint Pilate whiter still, and to further blacken the Jews.

Matthew’s Gospel says that Pilate washed his hands to declare himself innocent, and had the Jewish crowd cry out, “his blood be on us and on our children” (Matt. 27:25).

Pilate is thus exonerated and the Jews have been blamed ever since.

Other improbable details in the narratives further support this anti-semitic agenda of the Gospel authors. In Matthew, Mark and Luke, Jesus was tried on the same night he was arrested, which was the holy night of the Passover — a most improbable thing to happen on such a night. The prisoner could certainly have been kept till another time. Besides, the Torah commanded that judgements only be rendered in daylight. The improbabilities multiply.

The Gospel of John is the only Gospel to claim to have been written by an eyewitness. It may be significant in this context, therefore, that this Gospel says that it was Roman soldiers who arrested Jesus, assisted by Temple guards. There was no priestly trial by night, but only a private hearing before the high priest. Nonetheless, John still shows that it was the Jews who were stage-managing the proceedings from behind the scenes the whole time.

So why the need to vilify the Jews and exonerate the Romans?

Spong’s explanation is that the Gospels were written either during or in the wake of the Roman war against the Jews in which the city of Jerusalem and its Temple were destroyed.

This means that each gospel inevitably reflected either that war of the tensions of the anti-Jewish sentiment that followed that war’s conclusion.

So bitter was this war that the Jews, especially the Galilean Jews and the orthodox Jewish leaders in Jerusalem, became anathema to the Romans for the next few generations. The Christian Church, already alienated from the rigid orthodoxy of Judaism and becoming les Jewish and more gentile during these years, thus attempted to gain for its members the favor of the ruling Roman authorities. (p. 274)

Again to depart from Spong for a moment, for those who prefer to date the gospels even later, as late as the early to mid second century, the Roman world was wracked by ongoing Jewish rebellions including throughout Cyrene, Egypt and Syria. These culminated in the second Jewish revolt against Rome under Bar Kochba in the early 130’s.

Paul’s evidence concerning Judas

Though Paul does not mention the name of Judas, he does in his writings reflect an understanding that there were no defectors among the twelve.

The earliest expression of the death of Jesus and his subsequent resurrection is in Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians. Note 1 Corinthians 15:3-5

For I delivered unto you first of all that which I also received, how that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures;

And that he was buried, and that he rose again the third day according to the scriptures:

And that he was seen of Cephas, then of the twelve:

Spong emphasizes this:

Please note that this Pauline text said that the risen Jesus appeared “to the twelve”! The traitor had neither been identified nor removed in these early years in the writings of Paul. The betrayal by Judas was clearly a late-developing tradition with which Paul was not familiar. By the time the gospels of Matthew and Luke had been composed and the Judas story had entered the tradition, this anomaly had been noticed and rectified so the appearance of the risen Christ was, in those narratives, said to have occurred only “to the eleven.” (p. 275, my emphasis)

Another departure from Spong: 1) That reference to “the twelve” is of questionable authenticity. It may well even have been added after Paul’s lifetime. See Apocryphal Apparitions by Robert M. Price for this case.

2) The early Church Father Justin Martyr, writing around 140 c.e., also only knew of “the twelve”. See chapter 39 in The First Apology, In chapter 50 of the same document Justin says the twelve fled after Jesus was crucified (not before) and that Jesus appeared to them after his resurrection to ordain them as apostles. There is no suggestion of anyone lost. Chapter 106 of Justin’s Dialogue with Trypho confirms this belief of Justin’s, and adds that the disciples repented after they had fled at his crucifixion.

If this reference to the twelve is post-Pauline, and if Justin Martyr was not familiar with a Judas story as late as around 140 c.e., we may have further indications that the Gospels as we know them in their canonical form are indeed products of the second century.

Paul’s evidence confirmed by the Gospels

That Paul assumed a “complete twelve” in existence at the time of the resurrection appearances of Jesus — that is, no Judas betrayer who had left the group — is confirmed by places in the Gospels that also assume that none of the disciples would defect. Once again, we see evidence in the Gospels that the Judas narrative was a later addition superimposed on an earlier tale that knew nothing of his betrayal.

Jesus said to them, “Truly I tell you, at the renewal of all things, when the Son of Man sits on his glorious throne, you who have followed me will also sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel.

Jesus is assuming here that Judas will be among the twelve at his return.

You may eat and drink at my table in my kingdom and sit on thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel.

This passage in Luke is from the scene of the Last Supper. It appears an earlier version of Luke knew of no Judas betrayal, but that Jesus could declare at this moment on the eve of his death that all twelve disciples would be with him in the kingdom.

Everything about the Judas narrative screams that this was a late-developing legend created out of the midrashic method to serve the apologetic needs of the Christians in the last half of the first century [I would keep in mind the possibility of the early to mid second century] in order to transfer the guilt and blame for Jesus’ death from the Romans to the Jews. (pp. 275-6, my emphasis)

The following portion of this post details the variations in the narratives of the different Gospels about Judas. Inconsistencies are noted in more detail than the preceding part of this post.

The Earliest Appearance of Judas as Traitor

The Gospel of Mark is generally accepted as the earliest of the Gospels, often said to have been composed around 65 to 70 c.e.

Mark 3:14-19: First Judas is simply listed here among the twelve. He is the last listed and said to be the one “who betrayed him/Jesus”.

And Judas Iscariot, one of the twelve, went unto the chief priests, to betray him unto them.

And when they heard it, they were glad, and promised to give him money. And he sought how he might conveniently betray him.

This is the second appearance of Judas in Mark. Mark gives us no motive for his action. The offer of money came only after his determination to betray Jesus. Readers are not informed what the betrayal hoped to accomplish. Nor is it explained why a betrayal was necessary to arrest Jesus. True, Mark had earlier said the chief priests were fearful of arresting Jesus lest a riot among the people result (Mark 14:2). “Judas, however, was not a party to that conversation.“

Then came the Last Supper. Here the betrayal was discussed but Judas was not mentioned.* Jesus is quoted as saying the betrayer would be one of the twelve, and that this was destined as a fulfilment of prophecy. None would escape his fate.

And as they sat and did eat, Jesus said, Verily I say unto you, One of you which eateth with me shall betray me.

And they began to be sorrowful, and to say unto him one by one, Is it I? and another said, Is it I?

And he answered and said unto them, It is one of the twelve, that dippeth with me in the dish.

The Son of man indeed goeth, as it is written of him: but woe to that man by whom the Son of man is betrayed! good were it for that man if he had never been born.

Following the Supper Jesus is said to lead his disciples out to the Mount of Olives, but there is no indication that Judas was not with them.*

Jesus returns from praying, tells his disciples that his hour had come, and that his betrayer was at hand.

Spong’s interpretation of the text is that “Judas appeared with the chief priests, the scribes, and the elders”, indicating that Mark wanted readers to understand that “the whole Jewish establishment was to participate in the betrayal.” I cannot comment on the validity of this reading, but can link here to the word generally translated “from” but that Spong apparently understands as “with”. (The word is “para” and others uses of it in Mark can be seen via the link.) Or maybe Spong simply misremembered the biblical text. But since the mob are said in most translations to have been sent by the chief priests, etc., it hardly males any difference regarding Mark’s portrayal of the culpability of all Jews in the betrayal.

But apart from the anti-semitic purpose of this image, Spong remarks on the way the whole scene leaves hanging in the mind of the reader how Judas arranged to gather such a delegation if he had never left the disciples at the Supper.*

The text identified Judas strangely as “one of the twelve,” as if he had never been introduced before*. . . . The Judas story sits on the text uncomfortably [see the eight notes marked * above], as if it has been imposed on a text in which it was not original. (p. 261)

. . . . the hour is come; behold, the Son of man is betrayed into the hands of sinners.

Rise up, let us go; lo, he that betrayeth me is at hand.

And immediately, while he yet spake, cometh Judas, one of the twelve, and with him a great multitude with swords and staves, from the chief priests and the scribes and the elders.

And he that betrayed him had given them a token, saying, Whomsoever I shall kiss, that same is he; take him, and lead him away safely.

And as soon as he was come, he goeth straightway to him, and saith, Master, master; and kissed him.

|

Departing from Spong for a moment here – – – For those who see Mark as the work of a literary master rather than an awkward patchwork assemblage of traditions and redactions, or for Augustinians and atheists toying with the possibility that the Gospel of Mark was the last, not the first, of the Gospels to be written, it is possible to explain the absence of explicit motive for Judas in terms of Mark’s larger theme and portrayal of the twelve. Mark may have created the twelve disciples as epitomes of the rocky soil of the parable of the sower. Led by Peter, a name meaning “rock”, and true to the form of the seed sown in rocky soil, the twelve begin their careers with Jesus famously, only to falter and fail under the pressure of persecution. Finally Peter, the first disciple of the twelve, denies Jesus (recall Jesus said that he would be ashamed of those who deny him at his coming) and Judas, the last named of the twelve, betrays Jesus. Judas’ action, like Peter’s, represents rocky soil, the type of person who lacks the depth to endure and survive under trials and tribulations. From this perspective, Mark’s disciples are seen as character types, and their actions are to be interpreted accordingly. Introducing any other motive would spoil this theme. Greed for money, for example, was one of the sins represented by the seed that fell among thorns, and is illustrated in the Gospel by the likes of the young rich man who asked Jesus what he must do to inherit eternal life. If this interpretation is correct, then Mark deliberately avoided suggesting Judas was motivated by greed for money. Spong has mentioned the common understanding that the description of Judas at the moment of betrayal as “one of the twelve” sounds as if the name is being introduced for the first time into the Gospel. An alternative view of this description is that Mark is stressing that Judas’s action is representative of the twelve. All twelve are stained by the representative acts of both Peter and Judas. Mark’s Gospel has also been interpreted as a polemic against the twelve. If this is indeed the case, it would, I think, strengthen the case for seeing Mark’s reference to “the twelve” at the moment of the betrayal by Judas as a deliberate twisting of the knife into them. |

The Gospel of Matthew’s Version of the Judas Story

The Gospel of Matthew (Spong uses the conventional dating of ten to twenty years after Mark’s Gospel) has many more details than are to be found in Mark’s Gospel.

- Judas went to the chief priests to ask for money for the betrayal — thus supplying a motive for Judas, ie greed.

- The amount of money involved is only found in Matthew. It was a trivial amount — the average price of a slave.

- Matthew had Judas speak at the Last Supper: When Jesus said, “One of you will betray me”, Judas asked, “Is it I, Master?”. “You have said so,” replied Jesus. Matthew 26:20-25

- At the moment of betrayal Matthew presents a second dialogue between Judas and Jesus: “Hail, Master”, said Judas; “Friend, why are you here?” asked Jesus.

- Only in Matthew does Judas reappear the following day to declare to the chief priests his repentance over betraying Jesus (Matthew 27:3-4)

- The chief priests rebuff Judas; Judas threw the money in the Temple and went out and hanged himself; the chief priests declare the money unfit for Temple service and use it to buy a field for burying strangers — thus supposedly fulfilling another prophecy. Matthew 27:3-10.

Spong remarks on the last point, Matthew’s attempt to tie the story of the purchase of the field to Old Testament prophecy:

This was a very strained effort on the part of Matthew to ground this developing Judas story in the texts of the Jewish Bible. The quotation from Jeremiah was neither accurate nor appropriate (see Jer. 32:6-15), but it does provide us with insight into how the mind of the gospel writer worked as he sought to develop his narrative in the midrashic tradition of the Jewish people. (p. 262)

Judas according to the Gospel of Luke and The Acts of the Apostles

Spong follows the conventional gospel trajectory of placing Luke as the third to be composed (5 to 10 years after Matthew and 15 to 25 years after Mark), and remarks on yet more details being added to the Judas tradition by this time. (Yes and no. My reading of Luke is that there is a different narrative about Judas being written by Luke with few, if any, of Matthew’s distinctive details.)

- Satan was now responsible for the act of betrayal. Satan possessed Judas to make him deliver Jesus into the power of the priests.

- Money was (as it was also in Mark’s Gospel) a subsequent reward offered, not a prior inducement.

- The reason for Judas’ role now became clear: Judas understood the need, and planned to arrange to have Judas arrested away from the crowds to avoid a riot.

- Even this explanation was strained for it would have been no trouble to follow Jesus and to stake out a watch where he could have been arrested quietly. But the betrayal story needed content and this was the best that Luke could do. (p. 264)

And the chief priests and scribes sought how they might kill him; for they feared the people.

Then entered Satan into Judas surnamed Iscariot, being of the number of the twelve.

And he went his way, and communed with the chief priests and captains, how he might betray him unto them.

And they were glad, and covenanted to give him money.

And he promised, and sought opportunity to betray him unto them in the absence of the multitude.

And when Judas does betray Jesus it is not in Gethsemane (as it was in Mark and Matthew) but at the Mount of Olives:

And he came out, and went, as he was wont, to the mount of Olives; and his disciples also followed him. (Luke 22:39)

In the “second volume” of Luke-Acts, we read an account of Judas’s demise that is incompatible with Matthew’s details:

Acts 1:16-20

[16] Men and brethren, this scripture must needs have been fulfilled, which the Holy Ghost by the mouth of David spake before concerning Judas, which was guide to them that took Jesus.

[17] For he was numbered with us, and had obtained part of this ministry.

[18] Now this man purchased a field with the reward of iniquity; and falling headlong, he burst asunder in the midst, and all his bowels gushed out.

[19] And it was known unto all the dwellers at Jerusalem; insomuch as that field is called in their proper tongue, Aceldama, that is to say, The field of blood.

[20] For it is written in the book of Psalms, Let his habitation be desolate, and let no man dwell therein: and his bishoprick let another take.

The Gospel of John’s Variations on Judas

New details in the Gospel of John

- The betrayal was the work of the devil: “The devil had already put it into the heart of Judas Iscariot, Simon’s son, to betray him” (John 13:2)

- Judas was the son of Simon, with the above verse sometimes translated as “Judas, son of Simon Iscariot”.(cf at John 13:2)

- At the Last Supper Jesus told the disciples, “One of you will betray me”; the disciples asked which of them would do this; Jesus said “It is he to whom I shall give the morsel when I have dipped it”; Jesus then gave the morsel to Judas; Satan then entered Judas; and Jesus said, “What you are going to do, do quickly.”

- Judas is thus said to have left during the Last Supper, giving him time to organize those needed to arrest Jesus, thus removing an inconsistency in the earlier Gospels.

- John concludes this departure of Judas with the dramatic symbolism of “And it was night”.

When Jesus had thus said, he was troubled in spirit, and testified, and said, Verily, verily, I say unto you, that one of you shall betray me.

Then the disciples looked one on another, doubting of whom he spake.

Now there was leaning on Jesus’ bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved.

Simon Peter therefore beckoned to him, that he should ask who it should be of whom he spake.

He then lying on Jesus’ breast saith unto him, Lord, who is it?

Jesus answered, He it is, to whom I shall give a sop, when I have dipped it. And when he had dipped the sop, he gave it to Judas Iscariot, the son of Simon.

And after the sop Satan entered into him. Then said Jesus unto him, That thou doest, do quickly.

Now no man at the table knew for what intent he spake this unto him.

For some of them thought, because Judas had the bag, that Jesus had said unto him, Buy those things that we have need of against the feast; or, that he should give something to the poor.

He then having received the sop went immediately out: and it was night.

When Judas reappears in John, it is in “the garden”, and it is with Roman soldiers assisted by some Temple police.

John 18:1-3

When he had finished praying, Jesus left with his disciples and crossed the Kidron Valley. On the other side there was a garden, and he and his disciples went into it.

Now Judas, who betrayed him, knew the place, because Jesus had often met there with his disciples. So Judas came to the garden, guiding a detachment [the original word means a cohort of 600 soldiers] of soldiers and some officials from the chief priests and the Pharisees.

There is no trial that evening before the Sanhedrin in John’s Gospel. Jesus was only taken to Annas, then to Caiaphas, then to Pilate’s headquarters.

Conclusion

This is the entirety of the biblical data about Judas called Iscariot. It is not a consistent picture. (p. 266)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

In fact, according to the top review on Amazon, Shelby had an axe to grind in writing Liberating the Gospels:

But, according to his Wikipedia, he rejects the virgin birth of Jesus, as well as his resurrection. And now Judas. The guy is a quasi-heretic. 🙂

He’s a strange one. Spong’s books were significant guide posts for me on my journey towards atheism. He thoroughly demolished all hope of finding any history in the New Testament, and then in a leap of mysticism (so it seemed to me) call readers to follow him into a mystical union with a nonhistorical but very spiritual idea of “Jesus”. Horses for courses.

Spong got his Master of Divinity degree from the Episcopal Theological Seminary, the largest accredited Episcopal seminary in the USA, which happens to be within walking distance of my home. Later, an honorary Doctor of Divinity was conferred by the same institution and another that is rather obscure. On October 22 of this year, a landmark 19th century chapel on the campus of the Episcopal Theological Seminary, where Gerald Ford attended services when he was Vice President, was substantially destroyed by fire. Perhaps it was a sign of God’s disapproval of Spong’s treatment of his gospels. 🙂

JW:

You’re back baby! Regarding “Mark’s” Judas:

http://www.errancywiki.com/index.php?title=Mark_14

“Mark 14:1 Now after two days was [the feast of] the passover and the unleavened bread: and the chief priests and the scribes sought how they might take him with subtlety, and kill him:

Mark 14:2 for they said, Not during the feast, lest haply there shall be a tumult of the people.

Mark 14:3 And while he was in Bethany in the house of Simon the leper, as he sat at meat, there came a woman having an alabaster cruse of ointment of pure nard very costly; [and] she brake the cruse, and poured it over his head.

Mark 14:4 But there were some that had indignation among themselves, [saying], To what purpose hath this waste of the ointment been made?

Mark 14:5 For this ointment might have been sold for above three hundred shillings, and given to the poor. And they murmured against her.

Mark 14:6 But Jesus said, Let her alone; why trouble ye her? she hath wrought a good work on me.

Mark 14:7 For ye have the poor always with you, and whensoever ye will ye can do them good: but me ye have not always.

Mark 14:8 She hath done what she could; she hath anointed my body beforehand for the burying.

Mark 14:9 And verily I say unto you, Wheresoever the gospel shall be preached throughout the whole world, that also which this woman hath done shall be spoken of for a memorial of her.

Mark 14:10 And Judas Iscariot, he that was one of the twelve, went away unto the chief priests, that he might deliver him unto them.

Mark 14:11 And they, when they heard it, were glad, and promised to give him money. And he sought how he might conveniently deliver him [unto them].”

Note the Markan intercalation. The annointing is the meat and the handing over are the loaves. Typical support for Markan priority as M and L tend to unravel the intercalation. AnyWay, the theme is the relationship of raising money verses Jesus’ passion. We have the obligatory Irony that the Disciples first complain that preparing for Jesus’ passion is a lost opportunity to raise money for the poor so in response they sell Jesus, presumably to raise money for the poor. Great stuff. Besides this irony and than the irony of having Jesus’ prophecy of being handed over fulfilled while the Priests are commanding him to prophesy (again, support for Markan priority) I think the main thing “Mark” is doing here is commenting on Paul:

http://www.errancywiki.com/index.php?title=Galatians_2

“Galatians 2:1 Then after the space of fourteen years I went up again to Jerusalem with Barnabas, taking Titus also with me.

Galatians 2:2 And I went up by revelation; and I laid before them the gospel which I preach among the Gentiles but privately before them who were of repute, lest by any means I should be running, or had run, in vain.

Galatians 2:3 But not even Titus who was with me, being a Greek, was compelled to be circumcised:

Galatians 2:4 and that because of the false brethren privily brought in, who came in privily to spy out our liberty which we have in Christ Jesus, that they might bring us into bondage:

Galatians 2:5 to whom we gave place in the way of subjection, no, not for an hour; that the truth of the gospel might continue with you.

Galatians 2:6 But from those who were reputed to be somewhat (whatsoever they were, it maketh no matter to me: God accepteth not man`s person)– they, I say, who were of repute imparted nothing to me:

Galatians 2:7 but contrariwise, when they saw that I had been intrusted with the gospel of the uncircumcision, even as Peter with [the gospel] of the circumcision

Galatians 2:8 for he that wrought for Peter unto the apostleship of the circumcision wrought for me also unto the Gentiles);

Galatians 2:9 and when they perceived the grace that was given unto me, James and Cephas and John, they who were reputed to be pillars, gave to me and Barnabas the right hands of fellowship, that we should go unto the Gentiles, and they unto the circumcision;

Galatians 2:10 only [they would] that we should remember the poor; which very thing I was also zealous to do.”

I think “Mark” is making the supposed historical observation that his criticism of the supposed historical disciples was that they were overly concerned with charity work compared to the Passion but they were willing to use the Passion to make money. Translated = to the extent the disciples promoted the Passion it was just to raise money and not the most important belief (guilt). The implication from Paul is that this was the motivation to allow Paul to go to the Gentiles. Note that the only time the disciples say it is okay it is tied to money. Money to be given to the the disciples. “Go raise money and give it to us. Than we will give it to the poor.” Yeah, right.

Joseph

I leave Judas a question mark. The case for his creation to give the passion a tangible villain is credible, and one within the trusted circle of disciples is good drama. That his name sets him up as a representative of the “Jews” who who betray Jesus is note worthy. Other evidence for his invention is less credible.

The line in Matthew about the disciples sitting on twelve thrones may reflect a pre Judas thinking in the church, but it is also possible that Jesus himself said it before Judas betrayed him. its location in the narrative of Matthew and Luke is likely their own placement and not reflecting the circumstance Jesus actually said such words. Note in Luke Jesus doesn’t specify the thrones. If it seems that Luke is promising a Judas a spot in heaven, that may be Luke fault as a story teller and not that their was an earlier Judas less Luke.

The same for Mark having Judas accompanying the disciples to the garden. Since he appears with the mob, it is logical to assume he came to the garden with them. Mark may have just neglected a narrative detail. others noted the discrepancy and corrected it(or if you like, Mark just figured the audience would figure that out when he was condensing Luke-Matthew.)

As for Paul’s 12, I suspect that if they did have such a group, who were to sit on 12 thrones Judging Israel, that A. if they lost one, particularly due to betrayal (if one died faithfully, then I guess they would go claim their throne), then a replacement would be found, unless they were cool with a tribe of Israel not getting their ruler. B. Paul mentions Peter then the Twelve, but most (all) list of disciples include Peter, so I suspect that “The 12” was the proper name of the group, no matter how many were present. There is no evidence Paul ever heard of a Judas, but this(his reference to the 12) can’t be used to argue there was no Judas (that he doesn’t mention Judas however can).

In terms of embarrassment, their is an issue of whether some one would put a betrayer right in Jesus inner circle, as either a potential slight to Jesus’ judgment, or that an illustrious group like the 12 would have a traitor in it’s midst. The potential harm to Jesus reputation don’t seem that great, he is hardly taken by surprise by Judas, and betrayal by a close friend might be an experience shared by a many in the latter Christian community. the slander of one of the 12 is a bit more unlikely. If they were all known and beloved by someone, then there might be objections to subbing out one to make room for Judas. It seems though that there was some confusion over who the 12 were by the time the gospels are made. Paul only mentions a couple, and given the missionary aspect of the Christian movement, they may not have been around together for long after the the resurrection visions.

So in summery, I’m tossed up on Judas.

Mark doesn’t mention any suicide by Judas. And if you reconcile/harmonize Mark 16:14 with John 20:24 then Judas was not dead but was present when Jesus made his resurrection appearance to the 11.

Mark 16:14 Afterward he appeared unto the eleven as they sat at meat, and upbraided them with their unbelief and hardness of heart, because they believed not them which had seen him after he was risen.

John 20:24 But Thomas, one of the twelve, called Didymus, was not with them when Jesus came.

There were only 11, not because Judas committed suicide, but because Thomas was absent. Hence, the Judas story was made up afterwards to explain why there were only 11 at the resurrection appearance, and was made up by those who didn’t know it was Thomas who was absent. Of course there are also Gnostic texts that refer to a Judas Thomas. So then, if Judas Thomas is both Thomas and Judas, then rather than killing himself, Judas just wasn’t there and then later came back demanding to see the nail scars?

Rey, Mark 16:14 is a late addition, probably a combination made of the the other resurrection accounts. it is missing from the earliest manuscripts. Look this up, it often appears as a foot note in modern Bibles. I hardly think John would assume that his readers would place Judas at the resurrection appearances without his explaining that Judas was there. John blackens Judas’ reputation beyond the other accounts, saying that he was only with Jesus to steal from their money bag. If Judas had a turn around, you would think that would be explained, from what we have in John, we can only presume Judas made of with his loot to live happily ever after.

Actually there was not betrayal at all, and the tradition of betrayal is due to an orwellian manipulation of language by generations of dishonest christian so-called scholars and biased translators.

Look up “paradidymoi” in a real classical Greek English lexicon, say the one published by Oxford University Press, and not the wad of crap produced by the lying scum at bible publishing houses. The word means “had over”. Get a concordance of the Septuaginint and the christer gospels, in every instance the word is used, EXCEPT where it is used with respect to Judas, the word has been translated as hand over or give over or something similar. INconsistent use of language by biased lying scum christian propagandists. In the e-pistols the word is used in relation to the gospels, do they intend to hand over or to betray the gosples. If you really want to get ambitious set up a search program and search the entire Greek pre medieval literature on the Perseus project. The word paradydimoi and its assorted conjugations always means handing over except when used by a post Jesus christian propagandist when referring to Judas.

Mebbee the Jesus dude was historical maybe not, but first the iggerent christers should at least learn how to read their own holey books for what is really there, rather than accepting their sheep masters lies about what is there. I mena come on guys, weren’t any of you ever the least bit interested in checking out what the black suit guy on the podium was ranting about every Sunday, just before passing tghe plate and sucking the bucks out of you?

I mean like dudes, the Jesus guy sashays into town, at the head of a parade with no permit, ticks of the authorities and then gets the guilts and has his cuz or bro hand him over to the man, before the real whomping action by the Roman pigs has a chance to start.

If you chirster dudes would quit feeding the priest, you could save enough bucks in a couple of weeks to buy a used Greek english lexicon and read your holey books for yourself and not have to trust the self serving parasitical priest guys interpretation that he force feeds you, Of course most hard core christers are not real big in the mental cohones department

Hello! I’m working through a study of the gospels, and I’m a little confused at what you’re arguing. It appears you’re arguing that Judas is an imaginary figure, made by Christians, to portray the Jews as the scapegoat. A major issue with your argument is that Jesus was a Jew. Most of his followers were Jews as well. Jesus was highly integrated in a thriving Jewish culture, as noted by archaeologists and scholars in the academic video series: From Jesus to Christ (PBS).

Further more, I cannot find in my Bible where Judas repents in Matthew, as laid by your initial foundation. Also, I’m worried about reading your writing – as it doesn’t appear credible – because you have not even taken the time to research your presumed “inconsistencies.” You seem to portray Gethsemame, the Garden, and the Mount of Olivies as three distinct locations, and not cohesive of the gospel writers. In fact, the garden and Mount of Olives are the same location, IN Gethsemane. I am not posting this to be disrespectful, or rude, I simply want to point out some areas for you to further research. Be careful what you read – just because it’s a book does not make it correct! Lastly, I’d love to hear what you think if you’re interested in discussing via email. Maybe I read this wrong, but just wanted to make a note for reader! I’ll admit, I did not read your whole post, because when you began with an unaccurate portrayal of “inconsitencies,” it did not give me the feeling of credibility. However, I admire your tenacious efforts to dig into scripture, and would encourage you to rely more on scripture than modern doctrine, as noted by Mark 13:23

Well, it’s certainly possible for some Christians to ignore cognitive dissonance on this topic. In the Gospel of John, it consistently describes Jesus’ rivals as “the Jews”, to the extent that, out of context, you could easily get the impression that Jesus is not Jewish.

There is a useful summary of the possible origin/meanings of the “surname” of Judas by Joan E. Taylor at

http://www.academia.edu/283224/The_Name_Iskarioth_Iscariot….

I forget where I read that it could also be traced to an Aramaic word for “money-bag” or “purse-keeper”.

The idea that Judas was from Judea rather than Galilee &c as part of Christian “antisemitism” was pushed by writers like the late Hyam Maccoby and integrates with the accusation that the New Testament is primarily responsible for “The Holocaust” – which is put on the back-burner when US “Christian Zionists” are enlisted to support Israel.

Regarding the authors (sometimes) dubious research:

The author states that, according to John, “a detachment of Roman soldiers accompanied by police from the chief priests and Pharisees”.

This is not at all correct, if one takes time to read the Greek. The NASB, for some odd reason, inserts the phrase “Roman cohort” (in John), but, this is simply not found in the Greek.

The author asks the question “Did the Sanhedrin assemble that night to condemn Jesus?”, then provides the answer of “no”, in regards to the account in the gospel of John. However, the gospel of John simply makes no mention, one way or the other, as to whether the Sanhedrin had assembled or not. All we know is that Jesus was first taken to Annas, then to Caiaphas at “the court of the high priest”. If this is a reference to a “legal court”, and not a “courtyard” (or other physical location) then as a court, it would have been an assembly. The gospel of John also notes that, after questioning by Caiaphas, “…they led Jesus from Caiaphas into the Praetorium”, where “they” presented charges against Jesus to Pilate. This presentation would not have been made by random guards sent to arrest Jesus.

In short, there is no definitive answer to the question “Did the Sanhedrin assemble that night to condemn Jesus?” in the gospel of John – meaning – unlike what the author says, the answer could not be a definitive “no”.

The author asks “Did Judas Repent”, and provides the answer of “no” in regards to the gospel of Luke.

Once again, the author is providing information that simply isn’t available. Unlike Matthew, Luke mentions nothing about Judas’ fate in the gospel. We learn about Judas’ fate from the book of Acts, as part of side note to the process of choosing his successor. But unlike Matthew, Luke tells us nothing about Judas feeling remorse, confessing his sin and returning the money. Nor does he tell us that Judas went away from the whole deal with a big smile on his face, buying a yacht with the 30 pieces of silver. Luke is simply silent on the topic of Judas’ demeanor after Jesus’ arrest. One can hardly find a definitive “no” answer to the question “did Judas repent” in looking at Lukes writings.

Someone else in this thread has already mentioned the location of the Garden of Gethsemane; I believe the contributor said the Mount of Olives was in the Garden of Gethesemane. I would have put it the other way around: the Garden of Gethsemane is actually on the Mount of Olives. But, in any case, the author has made it appear that the Garden of Gethsemane, “a garden”, and the Mount of Olives are all pointing to different places. This is hardly the case, if one simply looks at a map of Jerusalem.

I could go on — but – I won’t. Stuff like this turns me off, and makes it impossible to grant credibility to the rest of the article…

John 18:3 uses the Greek word σπεῖραν in all manuscripts (with only one dissenting one that uses σπεῖρα )

σπεῖραν according to all my lexicons and dictionaries means “cohort”. It refers to a military detachment of what was typically about 600 soldiers in Roman times.

Yes, σπεῖραν can indeed refer to a “cohort” – the group of about 600 roman soldiers.

However, it can also simply refer to any band, company, or detachment, of soldiers.

According to Thayer:

1. anything rolled into a circle or ball, anything wound, rolled up, folded together

2. a military cohort

a. the tenth part of legion

1. about 600 men i.e. legionaries

2. if auxiliaries either 500 or 1000

3. a maniple, or the thirtieth part of a legion

b. any band, company, or detachment, of soldiers

The word does not at all “uniquely” or “singularily” or even “always” refer to a Roman cohort.

It is very highly doubtful that Jesus was arrested by Romans; Pontius Pilate had no idea who he was, nor were the charges brought upon Jesus Roman charges – they were Jewish charges. It is also highly doubtful that 600 Roman soldiers would have been put under Jewish command for the sake of arresting one man. And the logistics of getting 600 soldiers from Jerusalem, across the Kidron Valley to the Mount of Olives (and Gethsemane) makes for a coordinated, full-fledged military action – something that would have had to have been coordinated with a half-dozen Centurions. And, the thing is this: they didn’t even know exactly where Jesus was; Judas had to lead them there.

So, there is no way that one can definitively say that a “Roman cohort” was sent to arrest Jesus, and from an historic perspective, it is entirely unlikely that it was anything but a band of Jewish guards.

Your comment would have been less misleading if it had said that “Roman” is not found in the Greek. “Cohort” clearly is there.

What was the usual word for the temple police?

(You seem to be interested in rationalizing the gospels to make them conform to normal history. They are clearly about fictitious and miraculous events and the authors themselves decide who they send to arrest Jesus — not Pilate. The author clearly wanted a huge band of soldiers along to arrest Jesus so he could demonstrate the awesome god-power of Jesus by having them all fall backwards when he spoke!)

You’re right, Neil… It would have been better to say “Roman” is not in the Greek…

Temple police? I’ve got no idea what they were called. However, both in Maccabees and in Judith, the word “cohort” is used (in the Septuagint), but the uses in those writings are in reference to (essentially) “any band, company, or detachment of soldiers”.

The word simply did not always refer to a group of 600 Roman soldiers. That’s why in the Darby translation, Youngs Literal Translation, New Disciples Literal Translation, and even the King James version don’t use the word “cohort” in this scripture, and certainly do not include “Roman” in there. The word literally *means* “something coiled up”, and can refer to a military unit (not only Roman – there are many writings where the word was used in reference to an entirely different national military).

Having said all that, the word (in this case) *could* have been used to represent a formal Roman cohort — except — making the decision as to how to accurately translate it in this (and any) case depends heavily on context. To decide “oh, this was a *Roman cohort*” in this case flies in the faceof reality: if Pilate had no idea who Jesus was, upon first meeting him, it is very highly unlikely that Jesus was of enough interest to Pilate to warrant his sending 600 soldiers out on a moments notice to go look for one Jew (whom he knew absolutely nothing about) out of a crowd of some 300k – 500k Passover pilgrims, especially when Pilate had no charges against Jesus at the time.

But, going back to my original post: I noted that the author stated that John says “a detachment of Roman soldiers accompanied by police from the chief priests and Pharisees” were sent to arrest Jesus.

The issue here is whether there were even any Romans in the bunch at all. Certainly, a secondary issue could be if there were 600 smakin’ soldiers in the bunch, but the author doesn’t go there. He uses the word “detachment”, and determines they were Romans. But, “Roman” is simply not there.

Had the author said “a detachment – possibly of Roman soldiers – accompanied by (blablabla)…” it would have been more palatable. But, even then, it would have been highly doubtful. The Sanhedrin had exactly ZERO control over ANY Roman soldiers at all…

An aside: I’ve got no comment on your comment in parenthesis…

I really don’t see what difference it makes to the overall argument and conclusion of Spong:

The natural reading of the Greek is what it generally means in similar contexts, a cohort, implying Roman soldiers. But I may be wrong and so might Spong be wrong on that detail and maybe there is evidence for a common usage of the word to refer to some other type of soldiers. So what, though?

It is a fallacy to say that Romans could not have been involved because your understanding of historical circumstances would not allow it. Historical circumstances are irrelevant in a narrative where people fall over backwards at the word of Jesus, people are raised from the dead, water turns to wine, a person can walk on water……

If Spong can get “Roman” out of that text, then the only way he can do it is by going the whole nine yards, saying it was, in fact, a formal “Roman cohort” – meaning, 600 smakin’ Roman soldiers show up to arrest ONE MAN that Pontius Pilate knew nothing of.

And, that would be the point at which I debated Spongs assertion – and, that’s all it is: an assertion.

Re: “Historical circumstances are irrelevant in a narrative where people fall over backwards at the word of Jesus, people are raised from the dead, water turns to wine, a person can walk on water……”

So, what do you bother dragging Spong into it for? You seem to already have the whole thing figured out. If the gospel narratives are as you describe, then you might as well feel free to just make up whatever understanding or interpretation you want. Doesn’t matter, does it?

On the contrary. I am very concerned to understand the text and get it right. I am not interested in “debunking” anything. I am interested in treating the sources in the same way historians treat other ancient documents and to follow the rules of historical research as practiced in mainstream historical studies. If you think the only alternatives are either attack/debunk or harmonize/believe then you need to have a look at what this blog is about…. See the About Vridar pages (authors’ profiles and “what is vridar”) linked in the right hand margin.

I too am very concerned to understand the text and get it right.

All I’ve done is offered my reasoning for saying that translating σπεῖραν as “Roman cohort” in this particular instance is, IMHO, not supportable. If we say “Roman cohort” (as I’ve repeatedly noted), then we’re talking about 600 Roman soldiers out to arrest one man – and, not on the orders of Pilate (who evidently had no idea who Jesus was when they met).

You come back with ” Historical circumstances are irrelevant in a narrative where people fall over backwards at the word of Jesus, people are raised from the dead, water turns to wine, a person can walk on water……”, and, that’s fine.

Feel free to ignore historical references. I don’t care. But, if you’re trying to get a grasp on the usage of the word “cohort”, then you need to understand (a) it can refer to basically any military “group”, and (b) it can refer to a formal Roman cohort, and, whenever you see the word, you have to make a decision as to which meaning really fits.

So, look… If you think “Roman cohort” fits here, that’s great. Evidently Sprong thinks 600 Roman soldiers, evidently without even a by-your-leave to Pilate (who had no idea who they were going to arrest, and had no expectations of ever seeing), showed up under Jewish leadership to arrest that one guy. If that works for you, then, write Sprong a “thank you” note.

It doesn’t work at all for me. Nor does it word for all the translators of those “literal” translations I noted earler, nor did it even work for the KJV. All I’ve done is to give my reasons why that particular word usage doesn’t work in this case.

Earlier, you said “You seem to be interested in rationalizing the gospels to make them conform to normal history. They are clearly about fictitious and miraculous events and the authors themselves decide who they send to arrest Jesus — not Pilate. The author clearly wanted a huge band of soldiers along to arrest Jesus so he could demonstrate the awesome god-power of Jesus by having them all fall backwards when he spoke!” – A comment, which at the time, I chose to ignore.

But now? I’m gonna take issue with it. I haven’t said a single thing to “rationalize” the gospel in the slightest. I’ve given a “word analysis”, based on whatever the text of the story is. It doesn’t matter if it’s Matthew or Homer. Even with Homer, writing fiction, you have to understand the meaning of words from the context of the story he’s telling. If Homer writes “the men walked over, then they said ‘do you need laundry done?”, you have to include the *previous* line, “Some women were at a stream washing clothes” in order to understand who “they” were that said “do you need laundry done”?

That’s the way these things work.

If you’ve followed my comments you will surely know that I don’t care a whit whether it was a Roman or any other type of cohort. I believe the word does naturally refer to a Roman cohort, but I have no problem with it turning out to be some other sort of cohort — as I thought I had made plain. My objection to your initial comment was that it was misleading and addressed more than simply the “Romanness” of the cohort.

As for your denial that you are rationalizing the gospels, I think you are deluding yourself. You are going way beyond the textual evidence itself with your insistence that it cannot refer to a Roman cohort, for example. You are relying upon factors external to the text and that read against the grain of the text — and the most common word usage — themselves.

Re: “You are going way beyond the textual evidence itself with your insistence that it cannot refer to a Roman cohort”

My “*insistence* that it cannot refer to a Roman cohort”????

I’ve offered my OPINION on the matter, and I’ve given reasons for my opinion. I’ve supported my argument. Sometimes, that’s what historians and linguists have to do (as best as I can make out).

I’m very glad to know that you “don’t care a whit whether it was a Roman cohort or any other type of cohort”, and, I’m really happy to know that you “have no problem with it turning out to be some other sort of cohort”.

I think we’re totally in agreement on those things. I’ve stated numerous times that it is my OPINION that “cohort”, in this case, simply cannot mean a “Roman cohort”, and I’ve offered support from my opinion, which comes not only from actual “word usage” in other texts, but also from the context of *this story itself*. For all I know, the author of this story was referring to a “cohort of alien biengs”, but it appears to me that since the author is writing a story about this character named Jesus, which supposedly takes place in ancient Judea, under the rule of a Roman named Pilate (and so on and so on), that in *this* story and in *this* “scene”, the “cohort” sent to arrest this character Jesus can not have been a “Roman cohort”, since that Roman procurator – in *this* story – did not even know who Jesus was at the time.

So, that’s my OPINION. Thus, my objection to the author (of this article) stating “factually” that it was a *Roman* cohort. The author might *believe* it to be so, and in that respect, I and the author differ. The author thinks it was a Roman cohort, and I don’t think so.

Could my opinion be wrong? Sure, of course. Doesn’t matter if it is. I can deal with that. But, rather than attacking my reasoning – and me, personally – by saying “I think you are deluding yourself” – it might be a tad more scholarly to simply present your reasons that you think the word “cohort”, in this instance, does in fact refer to an actual *Roman* cohort.

Re: “My objection to your initial comment was that it was misleading and addressed more than simply the “Romanness” of the cohort”.

Yep, and I thought that objection had been noted quite some time back, when I said “You’re right, Neil… It would have been better to say “Roman” is not in the Greek…”

We may not have an attestation to Judas in Paul. However, Judas is attested to in Mark, and, importantly, we have a shared tradition independent of Mark in Acts and Matthew of the “Field of Blood” (even though Luke and Matthew disagree where this name comes from). Surely there must have been a short reference to “Field of Blood” in Q. So, even if the reference to Judas in John ultimately goes back to embellishing Mark, we do have independent attestations to Judas, one from Mark and one which Mark was not aware of but was shared by Matthew and Acts (Q). These independent attestations seems to add significant weight to the idea that Judas was attached to the historical Jesus, and hence argues against mythicism.

“However, Judas is attested to in Mark, and, importantly, we have a shared tradition independent of Mark in Acts and Matthew of the “Field of Blood” (even though Luke and Matthew disagree where this name comes from). Surely there must have been a short reference to “Field of Blood” in Q.”

So far as I have been able to figure out, the consensus speculation about what was in Q rests on the assumption of Jesus’ historicity. Therefore, any historicist argument based on Q is circular.

There is no evidence for a “Judas tradition” that was drawn upon by authors or Matthew and Acts. (I don’t know of any other field where narrative variations are routinely explained by authors drawing upon “different traditions”. Usually the simplest explanation is offered: that the authors chose to vary an earlier story for their own thematic reasons.)

Apart from the fourth century testimony about Papias, all early non-canonical writings are unanimous in presuming the twelve remained twelve throughout without any Judas among them. The evidence is against, not for, any “Judas tradition” anywhere prior to the gospels and Acts.

The Papias account is patently anti-historical and its literary oddity may have been known to the author of Luke-Acts. But that’s hardly an endorsement for a historical “tradition” about Judas.

That Matthew varied Mark’s Judas story for theological reasons is plain enough, ditto for the author of our canonical version of Acts. Their sources are also clear: OT writings. They are midrashic narratives. That’s where the evidence of the Judas details points.

It is standard practice for scholars to present their own pet theories as “the truth” but genuine scholarship will examine all the evidence, including contrary evidence such as I have covered in the post above, and deal with all of it, not just the bits that support their theories.

I wonder if we might say, from a New Testament minimalism perspective, that it is unclear whether Mark’s story about Judas betraying Jesus was historical or not? It may be an example of Markan irony that Mark depicts Jesus as a well known apocalyptic prophet, who did such things as draw large crowds and had a triumphal entry into Jerusalem, that he needed one of his own to betray him to let the authorities know who he was (as though he was an unknown nobody).

Old Testament minimalism does not say that it is unclear whether the story of the patriarchs in Genesis is historical or not. It says the stories are clearly fictional, lacking as they do any independent evidence for historicity and conforming entirely to literary and theological functions.

New Testament minimalism says the same about Mark’s story of Judas’s betrayal of Jesus. The story makes no logical or historical sense. It is evidently derived from a retelling of other OT betrayal scenes and serves a clear theological function.

There is no evidence that anyone heard of the gospel story until the mid second century.

When we see a story growing in the telling over time we don’t normally assume that each new retelling was drawing upon independent sources somehow hidden from the first narrator; we more simply assume that authors like to exaggerate and add flourish to old stories they have heard to make them more colourful. Ehrman’s baseless surmising that later additions to stories came about from different independent sources is pure fabrication that would have no place outside biblical studies.

Carrier has some interesting thoughts on the origin of the Judas story. He writes:

If the resurrection—a “mythical event”—can be elaborately historicized in the Gospels, then this is a proof of concept that a “mythical person” can be elaborately historicized in the Gospels.

All too often, these stories run counter to the creation of Christianity and beggar the imagination. So, Jesus and the Twelve are in the Garden and in come the cops and they need Judas to identify Jesus? What? These are supposedly Temple officials who have seen Jesus at first hand in the Temple and other places. Couldn’t they tell which one was Jesus? And if they had not personally met the man, they had agents who had, otherwise why would they have been discussing what Jesus said and did all of the time?

And if the Romans were involved as “John” indicates, their methods were more “round them all out, we will sort them in custody” and hence no “finger man” was needed.

But even worse. If Judas’s fingering of Jesus were necessary and he had not done it, then Jesus doesn’t get caught, doesn’t get executed, and doesn’t get resurrected, where does that leave Christianity? This is as stupid as those who think that the “Jews killed our Lord and Savior Jesus.” So, Jesus dying and being resurrected wasn’t part of God’s plan? And if it was, was not Judas doing God’s will? If not part of God’s plan, why was Jesus asking that the task be given to another in his prayer in the Garden shortly before the arrest, implying he knew what was to happen?

If this were a script given to Hollywood producers it would be rejected soundly because of all of the plot holes, illogic, and confused motives.

All the more curious if Judas is a relatively late invention. Paul, Justin, Gospel of Peter, Ascension of Isaiah, know nothing of him. He emerged in one contrary branch of Christianity. But he does make sense if he was constructed as a symbol of the Jews.

Good day,

Let me try to track down the real story of Judas’ betrayal of Jesus by reading the text as composed by Mark, the inventor of this subplot. The devil is in the detail as Mark uses sophisticated wordplay, as I will show you.

I will highlight those details in Greek.

In fact this story takes of when the chief priests and scribes were looking for the covert means to arrest and kill Jesus. Now the words used for covert means used in the manuscripts is εν δολω. Not many commentators took the word to refer to a person, but actually it does:

In the Iliad a Trojan by the name Δόλων is a greedy spy who promises to Hector for a rich reward of horses and chariot to spy out the fleet of the Achaeans but gets caught in the act by Odysseus and Diomedes. To save his skin he betrays the positions of the Trojans and their allies to his captors and in the end they only reward him by cutting the traitors head off. His name is since used for any deceitful, treacherous or spying person.

Back to Mark’s story, the disciples are pissed off by the waste of the alabaster with expensive perfume and missing out on the possible proceeds because they are those poor mentioned, as even Jesus seems to hint at. Next Judas runs to the chief priests in order to betray Jesus. The chief priests promise him money and he is looking for an opportunity to deliver. He is in their service now!

Up to the moment of arrest near Gethsemane Judas is not mentioned again, though it is implied that he is present at the Last Supper. Jesus tells the disciples “εις των δωδεκα” who is dipping his bread with him will betray him.

Now to the scene of the arrest:

Judas “εις των δωδεκα” comes up, accompanied by a mob with swords and clubs sent by the chief priests, scribes and elders. He arranges a signal with them that he will kiss “φιλησω” the one they should arrest and lead away. When he has subsequently done that the armed mob moves in and grabs Jesus. But then a very odd detail is thrown in:

One of the ones present draws a sword and runs through the servant “δοῦλον” of the chief priest, cutting of “αφιλεν” the little ear “ωταριον”.

Now who is this servant and why is this even happening?

Look again at the words used and reminisce on what we read earlier and it becomes clear that Judas is the servant of the chief priest and gets the just reward of a traitor. Using “δοῦλον” and “δολω” is not just an intentional pun, but any good lexicon like LSJ will confirm that there are even enough spelling variants for both words to blur the difference completely. Furthermore “αφιλεν” can be construed as the reverse of “φιλησω”, translating as being unfriendly or even hostile. And the word “ωταριον” can also translate as little spy, as spoken in contempt, thus affirming and concluding my translation of this illusive account. It also explains why Mark never mentions Judas again, he was dealt with swiftly.

I see no reason to leap from identifying Judas with the servant of the high priest solely on the strength of a wordplay.

Wordplay is a factor I have also wondered about: see my notes at http://vridar.info/xorigins/homermark/mkhmrfiles/mkhmrpt2.htm#judas along with the little aside at http://vridar.info/xorigins/homermark/mkhmrfiles/judas.htm.

That’s wordplay in Greek. I’ll be interested in comparing it with hypothetical Hebrew wordplay behind the text as per the Charbonnel series.

Thank you.

I just don’t get it why you are not willing to make that leap, as you just provided even more ammunition to do so. Furthermore this reasoning is amply fortified by the logic inherent in the literary duty to make the traitor receive the just wages for his acts, not what was promised to him. The wordplay supports it, the logic demands it.

Logic does not at all “demand” it. Logic works by rules, not wishful demands. Nor is logic about “leaps”. Check out some sites addressing formal and informal logical fallacies, for instance one I have posted here.

Nice try.

However there is no question in my mind if this story is history. It is not. It is literature. As such different logic applies, and I made my case accordingly.

Thanks.

omg. logic is logic. it is as sure as 1+1=2. The same rules apply to literature and history and economics and sociology and psychology and biology and everyday life. You don’t get to change the rules when you decide you are working on fiction as opposed to reality. Logic is logic. Would you care to identify yourself here?

that you respond with “nice try” indicates to me you are here to argue, not seek. good-bye.