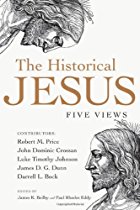

Robert M. Price lays out 5 ground rules for historical enquiry in his opening chapter, Jesus at the Vanishing Point, in The Historical Jesus: Five Views, edited by Beilby and Eddy. His intention is to attempt to allay resistance to his discussion of the possibility of a mythical Jesus by appealing to a set of methods rational and clear enough to be respected, if not in every case agreed upon without some modification.

Robert M. Price lays out 5 ground rules for historical enquiry in his opening chapter, Jesus at the Vanishing Point, in The Historical Jesus: Five Views, edited by Beilby and Eddy. His intention is to attempt to allay resistance to his discussion of the possibility of a mythical Jesus by appealing to a set of methods rational and clear enough to be respected, if not in every case agreed upon without some modification.

Most are familiar enough. They cover different territory from methods emphasized by Philip R. Davies (Gospels: Histories or Stories) and Neils Peter Lemche (Historicist Misunderstanding). Following is a summary of Price’s much fuller explanations for anyone interested.

1. The Principle of Analogy

When we are looking at an ancient account, we must judge it according to the analogy of our experience and that of our trustworthy contemporaries (people with observational skills, honest reporters, etc., regardless of their philosophical or religious beliefs). There is no available alternative. . . . So we will judge an account improbable if it finds no analogy to current experience. (p. 56)

It is not “antisupernaturalistic bias” that leads us to doubt Jesus’ ability walk on water or the sun standing still for a day. We are obliged to judge all reports and stories, whether biblical or nonbiblical, according to what we know from common experience. If a story like walking on water sounds more like our experiences of myths and legends (as when Greek gods and Buddha’s disciples walk on water), then we are sensible to think that a story of Jesus doing the same is also of that kind.

2. The Criterion of Dissimilarity

The idea is that no saying ascribed to Jesus may be counted as probably authentic if it has parallels in Jewish or early Christian sayings. (p.59)

Of course Jesus may have said things that overlapped with other sayings of his contemporaries. But we know that it was common enough for a well-liked saying to be attributed to various favourite rabbis. If so, this practice was likely to be true in the case of Jesus, too. Well-liked sayings could well have been attributed to Jesus, according to ancient Jewish literary practices. If so, this would very simply explain why we find contradictory sayings in the gospels on divorce, fasting, preaching to the gentiles, the time of the end. It appears that different church factions were ascribing their preferred teachings to Jesus.

If a saying could be seen to answer a need or have some direct use for a Christian community, then we are faced with deciding whether the saying by Jesus himself much earlier and in different circumstances was luckily applicable to the new situation, and had even more luckily been handed down from Jesus until its use was found in the church. Alternately, we can suspect that the saying was created for the immediate need and attributed to Jesus in order to give it a weight of authority.

As F. C. Baur said, anything is possible, but what is probable? And if the criterion of dissimilarity is valid, then we must follow unafraid wherever it leads.

Every saying attributed to Jesus in the Gospels was written by “church” scribes and for church needs. It follows, by the criterion of dissimilarity, that every saying we have of Jesus is a creation for church needs.

Price notes that this criterion has been watered down by many scholars on the grounds that, applied consistently, it leaves virtually no sayings left to attribute to Jesus. But of course, we cannot justify a complaint about a method solely on the grounds that it does not yield the results we want. Nor can we pick and choose our tools according to whether they will allow us to support a particular conclusion, such as a historical or mythical Jesus.

3. Remember what an Ideal Type means

An ideal type is a textbook definition made up of the regularly recurring features common to the phenomena in question. (p. 61)

Some have argued that the resurrection narrative of Jesus is so unlike anything found among contemporary beliefs and ideas that it is invalid to draw any comparisons at all between the two. But Price argues that an ideal type is a set of characteristics that can be used as a yardstick to measure what is generally true of a particular phenomenon. Buddhism is exceptional among religions by virtue of its absence of a belief in superhuman entities. But it contains enough other characteristics of the religion “type” to still be considered a religion, and its differences then become a focus to better understand what makes it a distinctive member of the general or ideal type.

4. Consensus is No Criterion

The truth may not rest in the middle. The truth may not rest with the majority. Every theory and individual argument must be evaluated on its own. If we appeal instead to “received opinion” or “the consensus of scholars,” we are merely abdicating our own responsibility, as well as committing the fallacy of appeal to the majority. (p. 61)

5. Scholarly “Conclusions” must be tentative and provisional, always open to revision

Our goal is to try out this and that paradigm/hypothesis to see which makes the most natural sense of the evidence . . . . We must seek the minimum of special pleading for fitting an item of recalcitrant evidence into the framework. (p. 62)

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Neil, I have purchased and read the book. I was simply amazed at the paucity of data that was brought forward to defend against Price’s stance. If I may summarize:

Crossan:

Gandhi existed! But I agree with most of what Price said, except that some ideal hero archetypes are real people, like Augustus. Paul wasn’t in a mystery religion (asserted with citation to 1 Cor 15:12-20) and finally, so what if he didn’t exist? But seriously, he did, and here’s what proves it — 2 things, first is: 4 sequential events 1. movement led by Jesus, 2. execution by Pilate 3. followers 4. still followers. Second is Jesus seems real to me when I read the gospels. The fact that other gospels change Mark proves that Jesus said stuff that people had to change … and stuff.

That’s one scholarly attempt at dealing with Price’s concerns by a mainstream scholar. I would say swing and miss, YMMV.

Second comes LT Johnson:

No, really the burden of proof is on those who believe in a historical Jesus, but we’ve got that taken care of. Oh by the way I agree with him a lot. First, Price ignores multiple attestation, and also the whole dying and rising Gods thing is so 19th century. See, a crucified and raised Messiah isn’t a dying and rising god. Nobody thought a Jewish peasant was an ideal type in the 1st CE in Palestine. 3 more things, 1st Josephus mentions Jesus twice, Tacitus mentions him and so does Lucian, 2nd Paul says Jesus was a Jew, he quotes Jesus on divorce, and Paul knew that Jesus had a brother, James. Finally, the gospels don’t quote the Torah exactly, and you could never read the Torah and come up with Jesus from it.

Swing and a foul ball.

JDG Dunn:

Ridicule Price, suggest that no serious scholar could believe this. Besides, Mark had the advantage of 40 years or oral tradition. Jesus was a Jew so the criterion of dissimilarity doesn’t apply to anything he said that was Jewish. If someone is an ideal type, they must have been quite a man. Direct quote “This is always the fatal flaw with the ‘Jesus Myth’ thesis: the improbability of the total invention of a figure who had purportedly lived within the generation of the inventers (sic), or the imposition of such an elaborate myth on some minor figure from Galilee. Price is content with the explanation that it all began ‘with a more or less vague savior myth.’ Sad, really.” I’m irritated by Price. He doesn’t mention 1 Cor 15:3, or that Paul preached Christ crucified, when crucifixion was a Roman punishment. Besides, the fact that Christ was a proper name when Paul was writing proves that Jesus was already the messiah by the time he wrote. Jesus had a brother that Paul met. Price’s argument is barrel scraping and has no self-respect. Price ignores the Acts! Price’s argument is unbalanced re; gospels. Of course they are midrash. But they might be midrash about Jesus. What we should do is find stuff in the gospels that isn’t in the OT and then feel that that was real. For instance, the Kingdom of God, who is that modeled on? Price’s thesis is what’s at the vanishing point.

Schoolyard taunts and not much else IMO.

DL Bock:

If Price is right, we’ve all wasted a lot of time. But Price believes in the Western Enlightenment. The problem is, if there is a God who acts in history, then he could have inspired the gospels and come to earth in the form of Jesus. How can you rule that out?

At this point I gave up, but will finish the summary anyway.

Price can’t explain how the sayings originated — therefore Jesus was real. Price dismissed Josephus. No Jews argued Jesus was a myth. Plus Tacitus and Suetonius and the Dialog with Trypho. Heck, even the Jesus Seminar thinks 20% of the gospels are real. As for his use of dissimilarity, great people change their cultures, so Jesus must have been exceptional. Josephus says there was a brother of James named Christ, and Jews said he was sorcerer. The Last Supper is in the epistles! The epistles speak of a resurrection! Cephas is the Peter of the gospels. Price doesn’t say where Jesus comes from. James was Jesus’ brother! Jesus isn’t like Attis because he is uncorrupted and doesn’t die every year like Attis did. I don’t buy the hero archetype stuff. All of us who believe in a historical Jesus are much more helpful in thinking about Jesus historically.

So … mainstream scholarship looks pretty much like an internet message board as far as I can see.

Thanks, Evan. Neat summaries 🙂 (I don’t think Crossan and the others were even trying to argue seriously. They ought to donate their royalties to charity.)

I also recall Crossan arguing that the real reason he is convinced that Jesus is historical is because there were 2 contradictory characterizations of Jesus in the early evidence. One had him as a nice gentle teacher, and the other as a soon to return avenging judge. And no-one would have decided to invent the second if the first was already doing fine as a myth — so it had to be all perceptions based on something historical??? But I’m going from memory here. I am willing to be corrected.

I really do need to pick up this book.

I don’t think Crossan and the others were even trying to argue seriously. They ought to donate their royalties to charity.

This is the point I was making in another post – I don’t think that the historicists take the question seriously enough to actually look for evidence and argue for it.

This is the surprising thing that is becoming clearer all the time: how weak the arguments of the historicists are. They clearly have not spent much time considering the mythical JC view. I think I might do a better job of arguing for Jesus’ historicity.