James and Tom have an interesting exchange on the evidence for the historical Jesus here:

2010-03-03

Another James McGrath exchange re the evidence for HJ

Musings on biblical studies, politics, religion, ethics, human nature, tidbits from science

James and Tom have an interesting exchange on the evidence for the historical Jesus here:

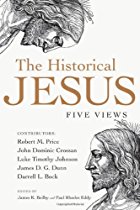

Robert M. Price lays out 5 ground rules for historical enquiry in his opening chapter, Jesus at the Vanishing Point, in The Historical Jesus: Five Views, edited by Beilby and Eddy. His intention is to attempt to allay resistance to his discussion of the possibility of a mythical Jesus by appealing to a set of methods rational and clear enough to be respected, if not in every case agreed upon without some modification.

Robert M. Price lays out 5 ground rules for historical enquiry in his opening chapter, Jesus at the Vanishing Point, in The Historical Jesus: Five Views, edited by Beilby and Eddy. His intention is to attempt to allay resistance to his discussion of the possibility of a mythical Jesus by appealing to a set of methods rational and clear enough to be respected, if not in every case agreed upon without some modification.

Most are familiar enough. They cover different territory from methods emphasized by Philip R. Davies (Gospels: Histories or Stories) and Neils Peter Lemche (Historicist Misunderstanding). Following is a summary of Price’s much fuller explanations for anyone interested.

When we are looking at an ancient account, we must judge it according to the analogy of our experience and that of our trustworthy contemporaries (people with observational skills, honest reporters, etc., regardless of their philosophical or religious beliefs). There is no available alternative. . . . So we will judge an account improbable if it finds no analogy to current experience. (p. 56)

It is not “antisupernaturalistic bias” that leads us to doubt Jesus’ ability walk on water or the sun standing still for a day. We are obliged to judge all reports and stories, whether biblical or nonbiblical, according to what we know from common experience. If a story like walking on water sounds more like our experiences of myths and legends (as when Greek gods and Buddha’s disciples walk on water), then we are sensible to think that a story of Jesus doing the same is also of that kind.

The idea is that no saying ascribed to Jesus may be counted as probably authentic if it has parallels in Jewish or early Christian sayings. (p.59)

Of course Jesus may have said things that overlapped with other sayings of his contemporaries. But we know that it was common enough for a well-liked saying to be attributed to various favourite rabbis. If so, this practice was likely to be true in the case of Jesus, too. Well-liked sayings could well have been attributed to Jesus, according to ancient Jewish literary practices. If so, this would very simply explain why we find contradictory sayings in the gospels on divorce, fasting, preaching to the gentiles, the time of the end. It appears that different church factions were ascribing their preferred teachings to Jesus.

If a saying could be seen to answer a need or have some direct use for a Christian community, then we are faced with deciding whether the saying by Jesus himself much earlier and in different circumstances was luckily applicable to the new situation, and had even more luckily been handed down from Jesus until its use was found in the church. Alternately, we can suspect that the saying was created for the immediate need and attributed to Jesus in order to give it a weight of authority.

As F. C. Baur said, anything is possible, but what is probable? And if the criterion of dissimilarity is valid, then we must follow unafraid wherever it leads.

Every saying attributed to Jesus in the Gospels was written by “church” scribes and for church needs. It follows, by the criterion of dissimilarity, that every saying we have of Jesus is a creation for church needs.

Price notes that this criterion has been watered down by many scholars on the grounds that, applied consistently, it leaves virtually no sayings left to attribute to Jesus. But of course, we cannot justify a complaint about a method solely on the grounds that it does not yield the results we want. Nor can we pick and choose our tools according to whether they will allow us to support a particular conclusion, such as a historical or mythical Jesus.

An ideal type is a textbook definition made up of the regularly recurring features common to the phenomena in question. (p. 61)