This post is about the miracles in what is generally considered the earliest written surviving gospel, the Gospel of Mark.

This post is about the miracles in what is generally considered the earliest written surviving gospel, the Gospel of Mark.

Dutch pastor and biblical scholar Karel Hanhart in The Open Tomb: A New Approach, Mark’s Passover Haggadah (± 72 C.E.) argues that Mark’s empty tomb story has been sewn together with semantic threads mostly from Isaiah in order to symbolize the fall of Jerusalem and its Temple in 70 CE and the emergence of Christianity as a new force among the gentiles. That is, the story of the burial and resurrection of Jesus was not understood as a literal miracle about a person being buried in a tomb and rising again. The first readers, with memories of the national calamity and Jewish Scriptures fresh in their minds, would have recognized instantly the many allusions in Mark’s closing scene of the empty tomb to the Temple’s fall, the end of the old order as predicted by the Prophets, and the promise of the body of Christ surviving and thriving throughout the nations post 70 CE.

A later or more geographically distant generation for whom the fall of Jerusalem had little personal significance would easily have lost sight of the original meaning of the burial and resurrection miracle and read literally the narrative of Joseph taking Jesus’ corpse from Pilate and placing it in the tomb, his rolling the stone to block the entrance, the women coming to anoint the body, their seeing the young man inside and running off in fear when he tells them to tell Peter where to find Jesus.

I will not in this post engage with Karel Hanhart’s specific arguments identifying the “Old Testament” and historical sources of Mark’s closing scenes. That’s for another time. Here I take a step back and look at the reasons we should read Mark’s miracle stories symbolically rather than literally. Be warned, though. I do not always make it clear where Hanhart’s arguments end and my additions begin. Just take the post as-is. If it’s important to know the difference then just ask.

Form critics long ago categorized the miracle stories into different types: healings, exorcisms, nature miracles. Classification like this has allowed scholars to say some types are historical and others not. We can imagine dramatic healing or exorcism that is largely performed through powerful psychosomatic suggestion. But nature miracles? Walking on water? Nah.

The trouble with this division, as Hanhart points out, is that the Gospel of Mark makes no such distinctions in the way any of the miracles are narrated. The narrative audience response is always the same: fear and astonishment. So let’s ask the question: What was “Mark” doing? Was he expecting his readers to take the miracles — all of them — literally or symbolically?

And if we answer, “Symbolically”, then surely we should include the final miracle — the empty tomb story — in that answer, too.

None of the Synoptic evangelists made such a distinction [healing miracles, nature miracles, . . .]. And Mark placed the open tomb story on the same literal or symbolic plateau, or both, as the stilling of the storm and the transfiguration. The audience response was the same in each case, one of awe and fear (4:41; 16:8). (p. 5)

And if we answer symbolically, we need to explain what message Mark was trying to convey.

Hanhart points to the following reasons Mark gives readers to enable them to understand that he is not writing a literal history.

One of these reasons is the repeated silence as a response to the miracles. This silence is especially bizarre given that it is sometimes the direct result of Jesus command to “tell” others about what they have seen. Conversely, when he commands silence, people tell. So the women who see the miracle at the empty tomb are commanded to tell Peter and the other disciples but they tell no-one; the leper who is cleansed and commanded to be silent tells everyone. There is something bizarre going on here. Or should we say something symbolic, coded. It is hardly a narrative about people behaving realistically.

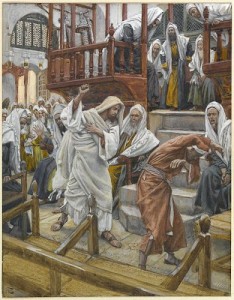

Recall also the first exorcism in the gospel. Jesus is in a synagogue in Capernaum when he is confronted with a man possessed. The demon in him shouts out the real supernatural identity of Jesus and Jesus orders it out of the man. The crowds do not respond with, “What a great miracle!” Oddly, what they say in response is “What new teaching is this?” (Mark 1:27)

Now that reminds us of what Mark writes after he tells us about Jesus teaching a lot of parables from the boat to people onshore. He concludes in Mark 4:34, “Without a parable he spoke not unto them.” That has led a few scholars to go so far as to suggest that the entire gospel is a parable. Is the first exorcism really a teaching parable for readers? Is that why the narrative audience speaks about it as a “teaching”? Such a response is not a natural or real-world one. Hanhart would say it is a coded clue to Mark’s meaning.

Then consider the occasion when Mark relates the Pharisees asking Jesus for a sign from heaven. Jesus replies: “No sign shall be given this generation” (Mark 8:12). But that’s crazy — if read literally. We have just read in the same gospel of Jesus performing one astonishing miracle after the other! He had just fed four thousand people with one boy’s picnic lunch. He had performed the same type of miracle not long before with 5000 people. How can Jesus say he would give no sign to that generation when we are reading up till that moment of one great sign after another being performed by Jesus?

Worse, even Jesus’ disciples, those closest to him who watch his every move and are in on-the-know, even these disciples ask Jesus how on earth they can feed 4000 hungry people in a desolate area even though only a short while earlier they had participated with Jesus in his miracle of feeding 5000. That sort of denseness among the disciples makes no sense at all in a historical or biographical narrative. Read literally the gospel story becomes a farce.

Then what about Mark’s Jesus predicting three times that he would rise again “after three days”? Hanhart himself notes what many of us have also questioned:

Did Mark not realize this “mathematical error? A child knows that if someone dies on Friday afternoon and is “discovered” to have risen on Sunday morning, the intervening period does not comprise three days. (p. 7)

Recall, further, the several names Mark uses that were surely meant to convey more than the simple identity of a place or a particular person. Legion, Jairus, Bartimaeus, Barabbas, . . . . And place-names, too. I won’t repeat details here since I’ve discussed these sorts of puns at least once before at some length. See More Puns in the Gospel of Mark for one such post and a link to an earlier one.

Then we have the curious doublets echoing echoing back and forth. In the opening scenes of Mark people come looking for Jesus very early in the morning, before daylight, but are unable to find him. In the closing scenes we have others coming to find Jesus but again he’s left — and it is just after daybreak this time. There is emphasis on the time and the time’s association with the same sort of event: looking for Jesus and not finding him. This sort of thing certainly sounds to me as though the author is writing something other than a straightforward historical narrative. Surely we are meant to read such echoes symbolically.

Certain words appear to take on a symbolic meaning through their repeated association with certain types of events. Doors are often mentioned in association with crowds trying to hear or get to Jesus. One of the most bizarre scenes is where a crowd is so large that four men who want Jesus to heal their paralyzed companion climb to the roof of the house and “hew out” the roof in order to lower him down to Jesus inside. And after going to all that trouble the healed man promptly gets up and walks right out through the front door with his pallet as if there was a royal carpet laid out for him — the crowds have suddenly vanished to allow him carry out Jesus’ command. Then at the end of the gospel we find Jesus is inside a tomb “hewn out” of a rock with the doorway barred by a huge stone — that later somehow moves aside by itself. What is going on here?

Mark often uses unusual words for things. Unless we know Koine Greek we need to read Mark with a good commentary to be aware of these words. The tomb is not a simple tomb or grave (taphos) but a “memorial tomb” or “monument” (mnemeion). Such things heighten curiosity, as Hanhart observes.

And we all know the mystery of the young man fleeing naked at the moment of Jesus being “handed over” to the priestly and Roman authorities. The several theories to explain this scene as biography or history do not satisfy. If he were really meant to be the author himself then how is it that he next appears in the tomb of Jesus? And why was there any attempt to grab him in the first place since Mark makes it clear that none of the disciples was in danger of being arrested once Jesus was taken? And why does the author inform readers that he was so unusually dressed? Surely no-one else was out there in the night air with nothing but a sindona (linen cloth) wrapped around their otherwise naked body? And why did Mark thrust in the face of readers the striking image of “naked”? And how many others were wearing the same type of sindona that was to be used to wrap Jesus’ body? How can we be reading literal history here?

And we all know the mystery of the young man fleeing naked at the moment of Jesus being “handed over” to the priestly and Roman authorities. The several theories to explain this scene as biography or history do not satisfy. If he were really meant to be the author himself then how is it that he next appears in the tomb of Jesus? And why was there any attempt to grab him in the first place since Mark makes it clear that none of the disciples was in danger of being arrested once Jesus was taken? And why does the author inform readers that he was so unusually dressed? Surely no-one else was out there in the night air with nothing but a sindona (linen cloth) wrapped around their otherwise naked body? And why did Mark thrust in the face of readers the striking image of “naked”? And how many others were wearing the same type of sindona that was to be used to wrap Jesus’ body? How can we be reading literal history here?

Nor can we overlook the many images in Mark’s gospel that evoke scenes from the Old Testament. Jesus travels towards the sea with a huge multitude following him and soon afterwards ascends a mountain from where he appoints twelve disciples to be with him. The parallels with Moses leading Israel to the Red Sea and establishing the twelve-tribed people of God at Mount Sinai have not been lost on commentators. When the blind man only begins to see after Jesus first stage of healing him he sees “men as trees walking”. Does Mark really want us to recall the parable of trees all moving to get together to anoint a king in Judges 9:8? If so, why?

And what do all of these semantic and narrative curiosities have to do with the historical background of the author and his original audience?

If we have so many indications throughout the Gospel of Mark that warn us against trying to read it literally, then what did the empty tomb story mean to the original readers?

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“The several theories to explain this scene as biography or history do not satisfy. If he were really meant to be the author himself then how is it that he next appears in the tomb of Jesus?”

I think it’s plausible that the author wanted us to think he was a witness to Jesus’ resurrection. This doesn’t mean he *actually* was, just that Mark lied and and hinted that he had really been there. Just like with the author of John saying he got his information directly from the beloved disciple, or the forged letters of Paul.

It’s also possible that the naked young man is symbolic; Richard Carrier argues this in “The Empty Tomb.”

Yes, I should do a post on the various theories attempting to explain this young fellow. Hanhart conveniently lists many of them. On the view that the young man in the tomb represents Mark himself, and of the other theories, Hanhart writes (with my bolding):

The crowds do not respond with, “What a great miracle!” Oddly, what they say in response is “What new teaching is this?” (Mark 1:27)

Describing the response of the crowd as he does wouldn’t necessarily represent, or attempt to represent, the entire range of their reactions, would it?

Didn’t Mary race to tell Peter and others what had occurred?

No, not in the original gospel. Its last sentence is:

“And they went out and fled from the tomb, for trembling and astonishment had seized them, and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.”

Fantastic post. But it left me wanting at least one symbolic interpretation for each of the events. Especially as relates to the Roman destruction of the temple and such.

Either way, very eye opening for me — a good Sunday School lesson. 🙂

We are familiar with the Passion scene drawing upon the Psalms and Isaiah. The empty tomb scenario likewise draws upon OT scriptures that have to do with the fall of Jerusalem and the first temple. I’ll be doing a more detailed post in the near future.

A fascinating read!

Just as in Sabio Lantz’s case, though, this blog entry left me wanting much more on the subject. I’m looking forward to reading more from you on the subject.

In one sense I followed up with these two posts:

There’s still much more to say, of course, but I am still processing much of the information myself. Will be posting more as I think through more, no doubt.

Thanks for the links and for maintaining such a treasure-house of information and analysis.

What you write here is preposterous. Over 2000 years of Christian belief, for which many people gave their lives, are against your mambo-jambo theories. Jesus rose from the grave and lives in many ways, but certainly not in you and your “teachings.”

So Christianity began before the resurrection? Or do you date the death of Jesus to before the year 14 CE?

I used to think that the resurrection of Jesus (33 AD) was the best explanation of the NT accounts and the development of Christian civilization with its flowering in art, music, philosophy and social codes, but sadly over the years have come to a very different conclusion. The old apologists like Morison, Lunn and later McDowell, and their sophisticated successors like Craig, Licona and Habermas are quite unconvincing if one really studies the NT, even in the light of scholarship within the Christian community from Raymond Brown, Pheme Perkins, Edward Schillebeeckx, &c. A good place to start a skeptical review would perhaps be the revised edition of Kris Komarnitsky’s “Doubting Jesus’ Resurrection”.

Many religions have started from small or even false beginnings, e.g. Islam, Mormonism or the JWs, and have had their martyrs. There were Nazis and Communists who sacrificed their lives for their beliefs, without any prospect of personality immortality. Martyrdom in itself does not validate the truth of the convictions held.

Maybe the women discovering the empty tomb was just a theological literary device. Because it was Jesus who died, women could be thought as reliable witnesses because Jesus was all about breaking down barriers. Recall Paul said “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus (Gal 3:28). This would fit in with the tearing of the curtain in the temple (Mark 15:38), and the Roman soldier saying ““Truly this man was the Son of God! (Mark 15:39).”

The maverick RC theologian Edward Schillebeeckx also held that the women at the tomb was an add-on, though there is nothing improbable about mourning relatives visiting a grave-site – despite pagan analogies with grieving female worshipers. Some apologists still suggest that the Pauline list of apparition witnesses started with Peter not Mary Magdalene and excluded named women, because female witness was not then considered legally valuable (this is contested), but also because they could have been considered as hysterical, Mary herself having been mentally ill (cf. Luke 8.2/?Mark 16.9).

Google: “Celsus. Hysterical woman” pp.1-3.

Mark’s portrayal of the death of Jesus was one of one of reconciling people to God through atonement. The tearing of the veil of the temple symbolized the removing of the barrier between people and God. The word’s of the Roman soldier that “Jesus was truly the son of God” symbolized the reconciling of the differences between Jews and Gentiles. The women being the witnesses to the empty tomb reflected the eroding of the inferior place of women and the unreliability of the testimony of women in the eyes of God. Hence, on this last point, Paul also said “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus (Gal 3:28).”

I think the women being at the tomb but being afraid to tell the men to go to Galilee is the perfect ironic ending for Mark.

I’d be willing to bet $5.00 that the whole empty tomb thing got started because some drunk, bored teenagers decided to play a prank and steal Jesus’ body from the grave, and then start the rumor that It was the end of the world (that the general resurrection had begun), and that Jesus had been seen raised from the dead. You could imagine Jesus’ followers hearing this rumor and out of Joy that Jesus had been raised, and terror that the end of the world had begun, hallucinating that the raised Jesus had appeared to them.

Dr. James McGrath offers an interesting naturalistic analysis of how belief in the resurrection might have begun among Jesus’ first followers.

The Pre-Pauline Corinthian Creed says:

“For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, and that He was buried, and that He was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that He appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve,” (1 Cor. 15:3-5)

If Mark read Paul, and John read at least one of the Synoptics, then the account of the crucifixion/burial/resurrection of Jesus may go back to only one source, the author of The Pre-Pauline Corinthian Creed, who cites only visions (hallucinations?) and scriptures as sources.

But McGrath says that, rather than speculating on the genealogical pre-history of these traditions in an attempt to attribute them to a single point of origin, it might be more persuasive to note what Paul explicitly says: that the first person to have the kind of religious experience was Cephas, whose failure in relation to Jesus would naturally create precisely the kind of psychological state that leads to some sort of experience that would help him alleviate his guilt and find catharsis. Once one person has a powerful experience, they may in turn facilitate others doing likewise. One can offer a naturalistic account of how things unfolded without any need to deviate from the depiction in our earliest sources.

What rot. So McGrath can bypass pointless speculation on the grounds that it is “not persuasive” — whatever that means. And then engage in his own speculation that he no doubt finds “more persuasive”. My god. So this is how biblical scholars work. And they call this scholarship???!!!!

It certainly doesn’t follow from the fact that an explanation agrees with what Paul says that it would “be more persuasive” than one that speculates away from the direction given by Paul. It’s all mere speculation in any case.

It’s not how historical research is done anywhere. It’s simply not historical research. Surely “only in the field of biblical studies” can people be paid heaps to get away with that sort of naval gazing. No wonder that scholars in other areas raise their eyebrows and smirk when these characters are come up in conversation.

It’s the whole “possible” doesn’t mean “probable” point that Carrier’s critiques are always emphasizing.

It’s far worse, actually. McG has no grounds that accord with normal document or source analysis in other historical disciplines for even imagining that a story with a theological purpose that appeared decades after Paul’s comment, that itself has very solid grounds for being regarded as an interpolation, could have any relationship to Paul’s comment at all.

McG is adopting a naive positivism (the very stuff he says he opposes in others — but which we have repeatedly established in the past he simply does not even understand!) by interpreting an unprovenanced narrative as depicting a reality “out there” that he can refer to as if it has some real existence and is not, in reality, a construct in the author’s and in his own mind. Constructs are created for very particular reasons, and McG uses this imagined reality (derived from a mere unprovenanced theological narrative) as if it were a real living historical event in order to give meaning to his own belief system. They need to be critically examined and tested, not projected as reality.

He fails to see that all he is doing is reshaping the Christian myth to make it “more persuasive” to his “scholarly” mind.

But that’s what most Jesus scholars are doing anyway.

(Unfortunately Carrier has embraced some of these assumed myths himself as if they were external realities.)

@ Neil

Agreed.

For instance, the humorous scenario I proposed isn’t contradicted by what we know about the origins of Christianity, and may even be hinted at in the text:

(1) My scenario was: The whole empty tomb event could have gotten started because some drunk, bored teenagers who were tired of listening to Christians prattling on about the end of the world decided to play a prank and stole Jesus’ body from the grave, and then started the rumor that Jesus had been seen raised from the dead, and it actually was the end of the world (that the general resurrection had begun). You could imagine Jesus’ followers hearing this rumor and out of joy that Jesus had been raised, and terror that the end of the world had begun, hallucinating that the raised Jesus had appeared to them. lol

(2) And the idea of bored teenagers stealing Jesus’ corpse and starting rumors as a prank that (a) Jesus was raised and (b) that the general resurrection had begun, may even be suggested by the text. After all, the rumor was started by the teenager in Jesus’ empty tomb in Mark:

“…But when they looked up, they saw that the stone had been rolled away, even though it was extremely large. When they entered the tomb, they saw a young man dressed in a white robe sitting on the right side, and they were alarmed. But he said to them, “Do not be alarmed. You are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, who was crucified. He has risen! He is not here! See the place where they laid Him.… (Mark 16:5).”

(3) The point is, this scenario is a “possible” scenario used to construct a naturalistic account of how faith in the resurrected Jesus began. There are many other models. But as Dr. Carrier says, we don’t want to overstep the bounds of reason by saying we have a “possible” explanatory framework, therefore we have a “probable” explanatory framework. These reconstructions of the possible reasons behind the arising of faith in the resurrection are “only possible,” and therefore merely speculative.

I think picturing whether Paul had an empty tomb scenario in mind or just a spiritual resurrection depends on what the ancient Jews thought of as the end of days and the general resurrection of souls. Paul calls Jesus the “first fruits” of this general resurrection. Matthew thought the first stage looked like this:

51At that moment the veil of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom. The earth quaked and the rocks were split. 52The tombs broke open, and the bodies of many saints who had fallen asleep were raised. 53After Jesus’ resurrection, when they had come out of the tombs, they entered the holy city and appeared to many people.…

(Matthew 27:51-53)

Where and when Matthew thought subsequent stages would happen Matthew doesn’t say. But from him at least we know some Jews thought that the general resurrection of souls meant bodies rising from the graves.

On the other hand, maybe Paul doesn’t think Jesus rose bodily, leaving an empty tomb.

Some like to point to a few verses in support of their claim that it was a spiritual resurrection. Their go-to proof text for the non-physical resurrection is 1 Corinthians 15:42–44. Here Paul is contrasting the earthly body with the resurrected body. The earthly body is perishable, dishonorable, weak, and natural. The resurrected body is imperishable, glorious, powerful, and spiritual:

“So is it with the resurrection of the dead. What is sown is perishable; what is raised is imperishable. It is sown in dishonor; it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness; it is raised in power. It is sown a natural [psychikos] body; it is raised a spiritual [pneumatikos] body. If there is a natural body, there is also a spiritual body. (1 Cor. 15:42–44)”

So, Paul seems to describe our present, earthly bodies as ‘natural,’ and our future, resurrected bodies as ‘spiritual.’”

However, it may be they wrongly assumed that natural and spiritual mean physical and nonphysical, respectively.

The question is: What does Paul mean by the terms “natural” and “spiritual”?

Paul uses the exact same words earlier in his first letter to the Corinthians. He writes,

“The natural [psychikos] person does not accept the things of the Spirit of God, for they are folly to him, and he is not able to understand them because they are spiritually discerned. The spiritual [pneumatikos] person judges all things, but is himself to be judged by no one. (1 Cor. 2:14–15)”

Notice the natural person does not mean a physical person, but rather a person oriented toward human nature or soul. In fact, psychikos, which is translated “natural,” literally means soul-ish. Similarly, the spiritual person does not mean a non-physical, spirit person. Rather, it’s a person oriented toward the Spirit. Paul may be contrasting soul-led persons with Spirit-led persons. The contrast is not one of physicality, but of orientation.

Therefore, Paul may be explaining that the future resurrected body will be freed from slavery to the weak, mortal, dishonorable, sinful human nature. The resurrected body will be led, sustained, empowered, and made glorious by the Spirit.

If indeed Paul did write those words in that first epistle to the Corinthians. In Philippians 1:23 Paul infers that there is no resurrection us such but a migration of the soul straight to heaven (or at least to Christ). An interesting discussion of the bodily resurrection is the focus of Gregory Riley’s “Resurrection Reconsidered: Thomas and John in Controversy”. (My own notes from that work are not listed in the Categories — something I’ll have to fix — but appear only via a word-search and seem to be posted in engagement with Wright’s arguments.)