Associate Professor of Classics specializing in Hellenistic Judaism, Sara Johnson, may suggest an answer to the question implicit in this post’s title even though she does not address the Gospels directly. Johnson has a chapter in Ancient Fiction: the Matrix of Early Christian and Jewish Narrative (2005) discussing the way 3 Maccabees was composed to help shape Jewish identity in the Hellenistic world. One way it accomplishes its ideological goal is to blend history and fiction. Historical verisimilitude serves to anchor the Jewish reader to the “historical tradition” of the community, while the infusion of fictional elements ensure the correct message and proper identity are inculcated. A reader such as myself with a strong interest in questions of Gospel origins cannot help but wonder if the Jesus narratives were written for a similar purpose in the same literary tradition.

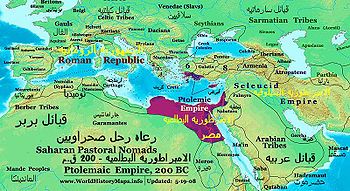

Sara Johnson’s chapter is “Third Maccabees: Historical Fictions and the Shaping of Jewish Identity in the Hellenistic Period”. 3 Maccabees, if you have not yet read it, is available on the University of Michigan Digital Library site. It’s not too long. It opens with a scene of one of the “great” battles in the Hellenistic era, the battle of Raphia, in which the forces of Ptolemaic Egypt (King Philopater) routed the Syrian army of Antiochus III, 217 BCE. On the eve of the Battle there is an attempt on Philopater’s life but he is saved by a Jew.

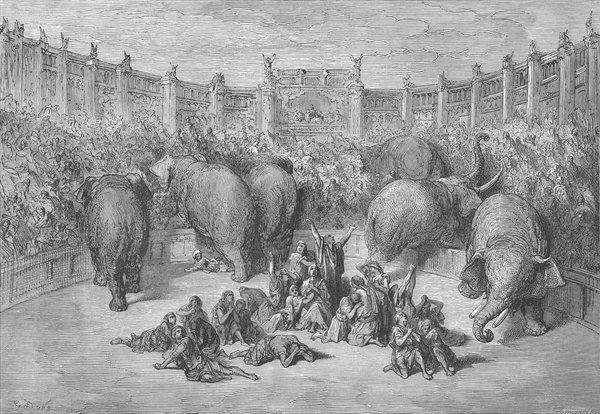

In the euphoria of victory Philopater invites himself into the most sacred area of the Jewish Temple to offer thanks to the divinity. (It is the custom of victorious kings to enter temples that way.) The Jews protest, we we would expect and Ptolemy is prevented by some divine action to from carrying out his plan. He returns to Egypt, enraged, and orders the Jews of Egypt be rounded up and crushed to death by drunken elephants. God maintains the suspense by holding off his several rescue missions to the very last moment, and finally changes Philopater’s mind altogether so that he even tells the world what wonderful and loyal folk all those Jews are. Jews who had apostasized under his pressure are quite rightly slaughtered instead.

The tale is a rich mix of genuine historical details and fables. Historical persons talk with fictional ones. Accurate details of the battle and the preliminary attempt on Philopater’s life are as detailed and accurate as we find in the works of the historian Polybius. The same accuracy is found in the Egyptian’s tour of the cities of Syria and offering of thanksgiving sacrifices in their temples.

This prepares the reader for a tale firmly rooted in the known facts of the past. (p. 86)

But the historical and fictional sit side by side:

When Philopater arrives in Jerusalem, however, we soon find ourselves jerked from the dry facts of history into the fantastic world of Jewish legend. Philopater wants to violate the customs of the Temple but is stopped by God. Angels stop the subsequent slaughter of the Jews by raging drunken elephants. We are reading a blend of “historical precision and blatant fiction.” (p. 187)

Philopater dictates two official letters in the narrative. The first, to order the branding of Jews with the ivy leaf of Dionysus and threat of executions; the second, to attribute the folly of the first letter to wicked advisers and to extol the virtues of the Jews. The letters are composed in a distinctive and formal style that suggests the bureaucratic language of the court. Ptolemy Philopater really was a worshiper of Dionysus. The author is striving for the illusion of realism.

By embedding fiction within the details of genuine history the author is creating for readers a new history with which they can identify.

Re-creating a sense of national identity often involves reinventing the nation’s past. The invention of self-consciously historical fiction about the past is a widespread phenomenon in the works of many Jewish authors. While Jewish fictions about the past were certainly highly entertaining, they were not written merely to entertain. They serve more importantly as a means through which to articulate a particular view of the past and therefore of Jewish identity in the contemporary Hellenistic world. (p. 190)

Such Jewish fictional tales vary in their genre (etymological legends, apocalyptic prophecies, historical narratives, romances), their content (Persian, Greek, Egyptian life), their language (Greek, Aramaic, Hebrew). Think not only of 3 Maccabees but also

- the Letter of Aristeas

- Esther

- Daniel

- Judith

- Tobit

- 2 Maccabees

- Tales of the Tobiads

- And of Alexander’s visit to Jerusalem

- Artapanus’s history of the patriarchs

- the Testament of Joseph

- Joseph and Aseneth

Yet, as varied as the texts are, they do have one thing in common: they all, regardless of the language or the genre in which the authors happen to be writing, employ fictions about the past in order to make a particular didactic point about identity. (p. 191)

Jewish identities varied. There were Jews of the Diaspora and Jews of Palestine; Jews who spoke Greek and Jews who spoke Aramaic; Jews who loved Hasmonean rule and those who loved gentile rule.

Thus it should not surprise us that the so-called Jewish romances reflect an infinite variety of ideas about the nature of Hellenistic Jewish identity. What is interesting is that all employ self-conscious historical fictions to get their point across. It would appear that the technique was infinitely adaptable. (p. 191)

The identity that 3 Maccabees wishes Jews to embrace is one in which they maintain their distinctive Jewish customs without cutting themselves off from the gentile world and without losing its respect. Those who do find fault with them will be the few whose characters are incorrigible. Jews are people whom the gentiles — especially those in the aristocratic circles — highly respect. It is Jewish devotion to God — even their willingness to die to maintain their customs — that ensures they have the character to live as cooperative, productive and loyal subjects in the pagan world. All of these qualities are demonstrated and recognized by the way the author creates an extreme situation to dramatize their dynamics.

[The author] systematically manipulates the historical elements in his narrative in such a way that they not only give a superficial appearance of historical credibility, but they also work to support the ideological point he is trying to make. The author of 3 Maccabees is very much concerned with communicating a certain kind of truth about the past, but that truth is ideological, not historical. It is more important to the author that his account of the past look and feel true, and that it support the truth of his main ideological point, than that it should actually be true in the historical sense . . .

The author uses historical details and the citation of documents to create a convincing illusion and to communicate his message more effectively. The version of the past invented by the author of 3 Maccabees was not historically true, but through the suspension of disbelief it expresses a deeper ideological truth. This is history not as it was, but as, in the eyes of the Jews of Alexandria, it ought to have been. (pp. 196-97)

Coincidentally I am also at the moment reading Todd Penner’s In Praise of Christian Origins in which the nature of ancient historiography is discussed at length. Penner concludes that a good number of ancient historians sought deliberately to write history as it should be, and that plausibility and narrative flow were more important than genuine past facts. History was didactic — writing a narrative that taught worth values. Penner and Johnson should meet up and nut out their differing perspectives.

Penner’s primary interest is the early chapters of the Book of Acts. But his discussion necessarily overlaps with the Gospel of Luke.

I have always felt a little uncomfortable with the perception that the Gospels are intended to persuade readers to embrace the Christian faith. To me they read like the sorts of narratives that could only be appreciated by those who come to them with faith to begin with. Certainly their differences point to rival interpretations of faith. But I prefer to think of the Gospels as works written in the tradition of the Hellenistic historical-fictions as discussed by Sara Johnson. They look to me as though they are laying foundations of a new historical and corporate identity for the earliest “Christians”. Just as the Pentateuch helped define the historical and ethnic or cultural/religious corporate identity of Jews (God only knows what their real origins were!), so the Gospels performed the same function for those Christ-cult sectarians who were looking for new roots and identities after the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple in 70 CE.

The historical trappings in the Gospels were just as necessary to accomplish this as were their fictions.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Great point. In Culpepper’s Anatomy of the Fourth Gospel he talks about the reader, the implied reader, the narrator, etc. If you stand back and consider the implications, it’s striking how much the reader is expected already to know, i.e., how much is implied or omitted.

So if the gospels are intended for Christians (i.e., not for prospective converts), does that make the thesis that they’re Greco-Roman biographies more likely or less likely?

Spot on. Their intent is to help early adherents understand their “new historical and corporate identity,” not to provide a biography of Jesus. The individual stories about Jesus aren’t there to tell us what Jesus “did” or “was like” but what Jesus “would do” and what Jesus “wants us to be like.” The stories aren’t “micro-history,” but parables that convey important truths.