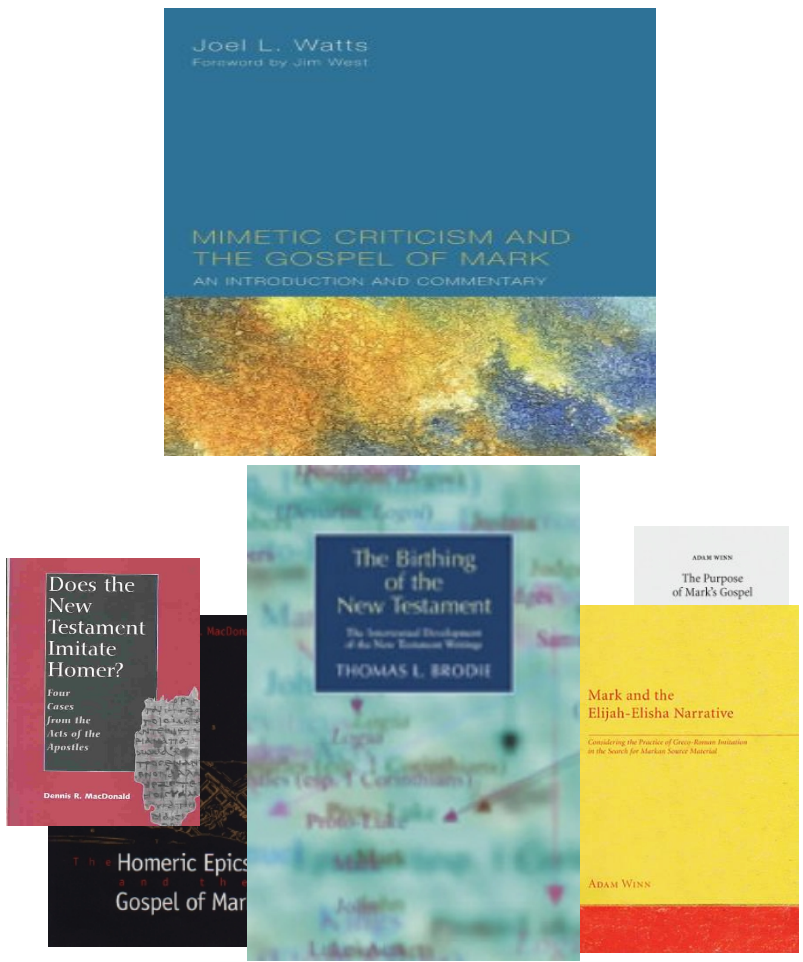

Rabid anti-mythicist Joel Watts has hailed the major work of mythicist Thomas L. Brodie, The Birthing of the New Testament, as “a masterpiece” in his own newly published book, Mimetic Criticism and the Gospel of Mark:

[Brodie’s] 2004 work, The Birthing of the New Testament, exploring the answers to the creation of the New Testament, stands as a masterpiece. His thesis is rather remarkable and easily within the realm of Roman literary tradition. . . . Brodie . . . has provided us with a better methodology . . . (Mimetic, p. 19)

In The Birthing of the New Testament Brodie, who has since “come out” confessing that his work led him to conclude Jesus did not exist (see various posts in the Brodie Memoir Archive), expounds in depth his methods and arguments for the literary sources of the Gospels, and effectively demolishes any need for a hypothetical “oral tradition” to explain any of their narrative input. The deeds, teachings and even the characters in the gospels are for most part re-writings of the Jewish Scriptures.

But Joel Watts, who has nothing but verbal slime to flick at the intellectual competence and personal character of anyone who leans towards a mythicist view, did not know that when he wrote that Brodie’s arguments were “a masterpiece”!

My my, what one will acknowledge if one does not hear the M word in what one is reading!

This brings to mind Brodie’s own observation that other scholars and teachers did not have a problem with his methods, only his conclusions:

He listened to me patiently, and looked carefully through some of the manuscript. I brought the conclusions to his attention.

‘You cannot teach that’, he said quietly.

I explained that I didn’t want to teach the conclusions, just the method, as applied to limited areas of the New Testament. If the method was unable to stand the pressure of academic challenge, from students and other teachers, then I could quietly wave it good-bye and let the groundless conclusions evaporate in silence.

It was a Saturday afternoon. He needed time to think it over. He would see me in a few days. (Brodie, Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discovery, p. 36)

Brodie learned to keep silent about the implications of his arguments in his earlier published works. He explains why in his Memoir. He was advised by publishers and scholars that his conclusions (not his methods) were unacceptable.

Other scholars who have advanced similar arguments have evidently been aware of the conclusions to which they intuitively lead. They have therefore made a point of explicitly reminding readers they are not questioning the historicity of Jesus or the fundamentals of the Gospel accounts. That they need to protest so consistently tells me they well understand the logical conclusions to be drawn from those arguments — but faith (or security of academic tenure according to Joseph Hoffmann) must, as always, override reason. More on this at the end of this post.

Even James McGrath endorsed it, (until . . . . ?)

Even James McGrath who, on learning that Brodie does not believe in the historical existence of Jesus wrote that while Brodie has made a “small number” of relevant comparisons, his methods are overall “problematic”, “unchecked parallelomania”, and “bizarre extremes”, praised this book of Joel Watts — presumably aware that Watts owes a good part of its thesis to Brodie’s work!

Watts’ book is “The newest element in the periodic table of scholarly tools . . . . bound to generate fruitful and illuminating discussion”, writes McGrath in his back-cover endorsement of the work.

Perhaps McGrath’s analogy of a new element on the periodic table was not so favourable, however. He goes on to explain that such elements are “highly unstable and liable to cause reactions”. Ever the master of equivocation.

I am disappointed that Joel Watts appears to have lacked the professional courage to defend his assessment of Thomas Brodie’s work against James McGrath’s recent scathing belittling of it now that Brodie has explained its implications for the Christ Myth.

And Adam Winn thought Brodie’s work was “important”

Joel Watts also relies heavily upon the scholarship of Adam Winn, in particular his 2010 work, Mark and the Elijah-Elisha Narrative: Considering the Practice of Greco-Roman Imitation in the Search for Markan Source Material. And Adam Winn, likewise, acknowledges Thomas Brodie’s scholarship as worthy of serious consideration:

The presupposition that Mark’s gospel relied primarily, if not exclusively, on oral tradition is greatly misguided and again is undermined by our knowledge of ancient writing practices. . . It is therefore of great importance that the question of Mark’s literary sources be reopened. . . .

Thomas L. Brodie . . . suggests Markan imitation of the Septuagintal Elijah-Elisha narrative in 1 and 2 Kings. Brodie’s work is, by his own admission, preliminary and cursory, and requiring further investigation of the topic. Yet, Brodie has laid important ground-work for such an investigation, noting numerous and striking parallels between Mark’s gospel and Elijah-Elisha narrative. (Mark, pp. 7, 10)

For Joel Watts, Brodie is a Giant

Dennis MacDonald‘s . . . methodology of introducing ancient literary theory to Gospel Criticism is well worth any Gospel critic’s examination. Thomas Brodie has provided help in narrowing down methodology and to offer some correction to previous conclusions. Adam Winn‘s continuing push into the undiscovered country has helped beyond words to clarify my own position. It is to these three giants that I shall now turn. (Mimetic, p. 11, my bolding)

Yes, Watts does borrow from Brodie:

I have borrowed the authority of MacDonald, Winn, Brodie . . . . (Mimetic, p. 34)

What of McGrath’s unsupported and wishful fancy that Brodie’s method is “bizarre” and “unchecked parallelomania”? Joel Watts would apparently strongly disagree!

Brodie has developed his own set of criteria for judging literary dependence. . . Brodie and Winn have given us solid criteria from which to move forward. . . (Mimetic, p. 23)

Is Watts aware that Brodie does not think that the Gospel narratives derived from oral traditions? Certainly:

Brodie also advises against dependence upon oral tradition, and follows his discussion here with one on oral tradition, something he considers “radically problematic.” (Mimetic, p. 21)

Later in Mimetic Criticism Watts is pleased to inform readers that another scholarly light he follows, Anne M. O’Leary, was also a student of Thomas L. Brodie. (p. 221)

There is one disappointing side to Watts’ treatment of Brodie, however. One will only find his name in his index under “Brody”.

Thinking it through

I wonder how Watts and Winn and others will react now that Brodie has publicly declared that the logical consequences of his arguments in The Birthing of the New Testament and other works, including his smaller monograph on the relationship between the Elijah-Elisha narrative and other writings in the Old and New Testaments, The Crucial Bridge, is that the authors of the Gospels were not relying upon reports of historical events and persons to create their stories. There is no need, nor indeed any room, for an historical Jesus when the full implications of the literary sources of the Gospels are understood.

Will they begin to slowly concede that Brodie was wrong after all? Will they quietly expunge Brodie from their bibliographies in future publications?

It is slightly amusing, in one sense, but also quite dismaying, to read the way many authors of brilliant scholarly works identifying Gospel sources in Jewish Scriptures, Haggadah and other writings, both Jewish and “pagan”, are simultaneously so quick and insistent to declare that they are not denying the historicity of words and deeds of Jesus.

The most recent one I chanced upon was yesterday evening, David Daube and his article from 1958, “The Earliest Structure of the Gospels”, published in New Testament Studies. After clarifying a very cogent argument that the four questions Jesus addresses in Mark 12 are constructed around the four ritual questions raised at the Jewish Passover ritual as found in the Haggadah, finds it necessary to explain:

This is perhaps the place to point out that the fact of a Christian exposition following the Passover eve liturgy does not diminish its historical value; rather the contrary. . . . There is no justification for doubting, on this ground, the happenings and sayings recorded . . .

More recently Dennis MacDonald must add in his conclusion:

Mark imitated Homeric epic and expected his readers to recognize it. This in no way denies Mark’s indebtedness also to oral tradition . . . Mark crafted a myth to make the memory of Jesus relevant to the catastrophes of his day. (MacDonald, Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark, pp. 189, 190)

Some authors, perhaps the more devout ones, do not need to be so explicit in these protestations: they only need to make fulsome worshipful confessions about the benefit of their work to all believing Christians and the work of Christ, etc. Thus Willard M. Swartley concludes the opening chapter of his book arguing that the Synoptic Gospels owed their fundamental narrative structure and themes to Jewish theological traditions and scriptures:

This contribution is thus dedicated to both the religious quest of persons seeking to understand the Christian faith . . . and the formation of the identity of Christian communities that treasure Scripture in its canonical form as empowerment for thought and life. (Swartley, Israel’s Scripture Traditions and the Synoptic Gospels: Story Shaping Story, p. 31)

Can one imagine an impressionable child who, on learning that his parents leave the gifts beneath the tree overnight, desperately continuing to insist they come from Santa nonetheless?

As a post-script I should add —

Of course legends and myths accrue to historical persons and there is no reason the same could not have happened in the case of Jesus — except! — except that the only evidence we have for Jesus IS the myth itself. In cases where historical persons were embellished by biographers with mythical tales we have clear evidence of those historical persons quite independently of the myths attached to them.

Remove the myths around Jesus and one is left with an invisible man. There is nothing there. Only hypotheses. The historical Jesus rests on nothing but an assumption. And that assumption is sustained in the academy by hypotheses upon hypotheses. (Of course he is also sustained among Christian believers by faith and authority.) Sure, there could have been an historical Jesus. There could have been an historical David, or Moses, or Joseph, or Abraham, or Noah . . . , too. And that’s my point. It’s all hypotheses and could-have-beens all the way down.

Related articles

- Blogging My Book (unsettledchristianity.com)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

The Pithom blog too seems to be softening its quibble toward mythicism. It used to be: “[Don’t] repeat the old errors of the Christ Mythers [since only] a strained case can be made [for them].”

Now (July 9) it’s: “[Within the Gospels there is] only a small core of history” and “all of Paul’s statements about Jesus are fully compatible with an understanding of Jesus as a channeled figure.”

Yes, I have softened my quibbles with ahistoricism. I don’t like the term “mythicism”, as the term “myth” generally connotes an untrue story composed orally and over a long period of time. I am still quite certain that ahistoricist arguments used 90 or more percent of the time when the historicity of Jesus is argued are quite terrible. I still like the KingDavid8 “Was Jesus A Copycat Savior?” page as it debunks many terrible ahistoricist arguments. If you look at earlier posts of mine (such as http://againstjebelallawz.wordpress.com/2011/08/22/hector-avalos/ ), I am found generally unsympathetic to ahistoricism. I became much more open to the idea that Jesus did not exist as I listened to some of Richard Carrier’s arguments and continued reading the Vridar blog in Google Reader. Indeed, I “liked” many Old Vridar posts long after I had read them. For how long have you been reading my blog, Bob?

Hm. After Googling “ahistoricism”, I found my “ahistoricism” terminology may cause confusion. How about “nonhistoricity”?

Historicism sounds like a natural counterpart to mythicism. I don’t like either word in this context. (“Historicism” reminds me of Popper’s The Poverty of Historicism — nothing to do with the way the word is used in this debate.) Theologians who believe in the historical Jesus can also speak of the Christ of Myth who is found in the Gospels. Christ Myth, in this context, has a common meaning for both sides of the debate. Why not simply “nonhistorical/historical” as the counterpart?

I only started reading your blog when I read your estimable support for Vridar against Watts. I’m glad I discovered you. I’m just a tradesman who’s interested in origins and I’m happy to find further direction from your blog after having read “The Quest for the Historical Israel” by Finkelstein and Mazar. I like the term, “nonhistoricity”. Could I recommend it for McGrath and others?

How about ‘fictional’?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fiction

What would the person advocating a completely fictional Jesus be called, then, though? A “fictionist”? Also, practically all scholars admit to there being at least some fiction in the New Testament, so “completely fictional” might work better than simply “fictional”.

How about “historian/theologian/classicist who advocates a version of the Christ Myth”? 🙂 We don’t normally assign labels for advocates of specific historical hypotheses, do we? We have Marxist or Postmodernist etc historians but those are overall approaches to the framework of historical inquiry, not references to whether or not they argue a particular thesis as an origin of an historical event, yes?

Fiction implies a conscious invention, I think. One problem is that the term “mythicist” obscures very different strands of hypotheses explaining Christian origins. I don’t think belief in the character Jesus began with a deliberate fiction, but some do.

I just noticed that Watts’ lastest blog was 3 minutes late and only consisted of “mrmee, mrmee, mrmee, mrmee”

Neil, I am at a loss for how to handle Brodie’s mythicism and I must admit it has made me reconsider the intellectual prowess of some mythicists. I haven’t read Brodie’s latest and might later so I cannot fully comment on my friend McGrath’s review.

I will stand by my remarks, which were written when his book was announced. I made the choice to go ahead and go with with them, even knowing what Brodie was going to say. (I had spoken with a someone who’d read the book in pre-pub)

As I said with DM, I can say about TB. His conclusions I do not support, but his methodology, research, and forward thinking ideas are gigantic and worthy of admiration. Brodie’s book, Birthing the NT, is outstanding, and I would use it in any NT class I taught. I do not think we should do Gospel Criticism without at the very least a long, heavy gaze towards Brodie’s work.

Well, well. Joel, you do realize, don’t you, that this is the very first time you have ever spoken to me in a civil manner? Thank you. It’s appreciated, whatever the motive.

Of course you do realize, though, don’t you, that everyone here knows darn well that you would never have picked up Brodie’s book (except to ridicule it) if you had ever known he was a mythicist from the outset. That’s the problem we are left with and would like to see resolved somehow. What if, just what if, Brodie’s work is considered average by the standards of those mythicists who engage just as seriously with the scholarship? How would you ever know?

Neil, are you really suggesting you rely on consensus as much as McGrath does? That’s a bit mind-blowing.

Historicists wouldn’t want Brodie, either, but I still find his methodology welcome. I mean, I don’t believe in Q (or proto-anything) which is against consensus and likely to raise eyebrows.

As far as having reading Brodie’s work on literary criticism/mimesis if I had known he was a mythicist… That is possibly the best question you’ve ever asked. Unfortunately, I’d say at this moment, I wouldn’t have. And I would be at a loss.

Maybe you have no idea of how great your loss for turning your nose up at so many other books that engage the scholarship from outside the box.

You will have to explain to me your reference to my supposed reliance upon consensus. Do you know how many others whose views I share and where they (the others) are from? It’s a pretty diverse field, as any quick survey of this blog will illustrate. No, Joel, my preference is for actually reading and engaging with arguments before I decide how I will refine or revise my thinking. Not like some who just google a few words, get a stash of website hits, and then chuck them all into the arena as “supporting evidence”. Not having a go at you, here, in particular. McGrath and Verenna are pretty good rivals of yours in that department, too.

If you can find where I fit in any “consensus” view do let me know. For that matter, if you can identify what you seem to have always just assumed is where I stand in relation to “mythicism” I would be even more surprised.

But I do like surprises. So I hope you do try.

Neil, I realize your Vulcan sense of humor cannot pick up on sarcasm and the inflection on the internet… (see, Vulcan is red, as is Australia). Anyway, when you say “Brodie’s work is considered average by the standards of those mythicists” that looks like a consensus statement. I was having a go at you.

You’re running rings around me this evening, Joel. I admit I cannot keep up with your wit. (I appreciate that you do explain jokes that I would otherwise miss.) When you spoke of “consensus” in this context I foolishly assumed you were speaking of scholarly academies, or of large numbers in there somewhere.

But I do encourage you to learn to read with some attention, or at least not quote half sentences so as to change the meaning of my original statement. I did not say “Brodie’s work is considered average by the standards of those mythicists” in order to suggest some or any sort of “consensus”, as you now infer.

But I did suggest a way you might surprise me. I’m still waiting.

Also, I posted on Brodie’s “outing” back in Jan.

The first non-crackpot argument against historicity that I became aware of was Earl Doherty’s, whose Web site I discovered in late 1999. His “Jesus Puzzle” convinced me that there was probably no real Jesus, but I wasn’t so sure that his particular alternative theory of Christian origins in general, or the intentions of the gospel authors, was correct. It occurred to me that a good generic term for my position would be “ahistoricist”. I’ve seen others use the term, but it doesn’t seem to have caught on much.

I’m still not sure that the Jesus of Nazareth character originated as a myth, as that term is ordinarily used by scholars in the relevant disciplines. I do believe, though, that the stories about him that were compiled about him the gospels were originally written by people who (a) did not think they were factual historical accounts and (b) did not expect their readers to think they were factual. That, to me, suffices to define the stories as fiction. I thus regard Jesus as a fictional character, at least. My jury is still out on the question of whether he was also a myth.

That’s what I say when I’m trying to be precise. In casual conversation, I’m often OK with saying that I tend to support mythicism.